Published online Nov 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6704

Revised: September 22, 2008

Accepted: September 29, 2008

Published online: November 21, 2008

AIM: To evaluate endoscopic and histopathologic aspects of acute gastric injury due to ingestion of high-dose acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with respect to some risk factors and patient characteristics.

METHODS: The study group consists of 50 patients admitted to emergency department with high dose analgesic ingestion (group I) with suicidal intent. Thirty patients with or without mild complaints of dyspepsia (group II) were selected as the control group. The study group was stratified according to the use of type and number of analgesics. Endoscopic findings were evaluated according to the Lanza score (LS), expressing the severity of the gastroduodenal damage and biopsies according to a scoring system based on histopathologic findings of acute erosive gastritis.

RESULTS: Gastroduodenal damage was signifi-cantly more severe in group I compared to group II (P < 0.01). The LS was similar in both groups Ia and Ib. However LS was significantly higher in patients who had ingested multiple NSAIDs (group Ic) compared to other patients (P < 0.01). The LS was correlated to age (P < 0.01) and total amount of drug ingested (P < 0.05) in group I; but it was not correlated with Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection or duration of exposure (P > 0.05). The biopsy score (BS) was higher in group I than group II (P < 0.01), and higher in group Ib than group Ia (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: The histopathologic damage was more severe among NSAID ingesting patients compared to those ingesting only acetaminophen and there is no significant difference in the endoscopic findings between the groups. There is no significant difference in the LS between the groups. This lack of significance is remarkable in terms of the gastric effects of high-dose acetaminophen.

- Citation: Soylu A, Dolapcioglu C, Dolay K, Ciltas A, Yasar N, Kalayci M, Alis H, Sever N. Endoscopic and histopathological evaluation of acute gastric injury in high-dose acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug ingestion with suicidal intent. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(43): 6704-6710

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i43/6704.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6704

| Drug | Dose (mg) |

| Acetaminophen | 4000 |

| Aspirin | 4000 |

| Etodolac | 1200 |

| Flurbiprofen | 300 |

| Ibuprofen | 2400 |

| Naproxen sodium | 1375 |

| Grade | Scale |

| 0 | No visible lesions |

| 1 | Redness and hyperemia in the mucosa |

| 2 | One or two erosions or hemorrhaging lesions |

| 3 | 3-10 erosions or hemorrhaging lesions |

| 4 | > 10 erosions or hemorrhaging lesions or an ulcer |

| Score | Microscopic findings |

| 1 | Superficial epithelium is intact, edema at superficial lamina propria, dilated and congested capillary structures, extravasated erythrocyte and tiny fibrin clots |

| 2 | Multiple focal scattered erosions + 1 |

| 3 | Disappearance of superficial epithelium, presence of proteinose materials on the surface of epithelium, diffuse hemorrhages within lamina propria, transmural ischemic necrosis + 2 |

| LS (median) | BS (median) | ||

| Group | Patients | 2.30 ± 1.18 (2) | 2.26 ± 0.83 (2.5) |

| Control group | 0.77 ± 0.57 (1) | 1.47 ± 0.73 (1) | |

| P | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Age | r | 0.391 | -0.078 |

| P | 0.005 | 0.592 | |

| History of gastric complaints | Positive | 2.36 ± 1.43 (3) | 2.09 ± 0.83 (2) |

| Negative | 2.28 ± 1.12 (2) | 2.31 ± 0.83 (3) | |

| P | 0.809 | 0.4 | |

| Smoking | Yes | 2.08 ± 1.29 (2) | 2.24 ± 0.88 (3) |

| No | 2.52 ± 1.04 (2) | 2.28 ± 0.79 (2) | |

| P | 0.234 | 0.949 | |

| Food intake | On full stomach | 2.36 ± 1.17 (2) | 2.27 ± 0.80 (2) |

| On empty stomach | 2.17 ± 1.24 (2) | 2.23 ± 0.90 (3) | |

| P | 0.576 | 0.964 | |

| H pylori | Positive | 2.08 ± 1.19 (2) | 2.32 ± 0.75 (2) |

| Negative | 2.52 ± 1.15 (2) | 2 20 ± 0.91 (3) | |

| P | 0.204 | 0.743 | |

| Duration of exposure | r | 0.14 | 0.099 |

| P | 0.332 | 0.492 | |

| Total drug dose (as multiples of maximum daily dose) | r | 0.353 | 0.219 |

| P | 0.012 | 0.127 | |

| Ingested drug | Acetaminophen only | 1.89 ± 1.18 (2) | 1.94 ± 0.87 (2) |

| NSAID only | 2.54 ± 1.21 (3) | 2.58 ± 0.70 (3) | |

| P | 0.086 | 0.013 | |

| Multiple NSAIDs | Yes | 3.40 ± 0.70 (3.5) | 2.50 ± 0.85 (3) |

| No | 2.02 ± 1.12 (2) | 2.20 ± 0.82 (2) | |

| P | 0.001 | 0.256 |

Analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen are extensively used pharmaceutical agents. NSAIDs are well known and widely used for their anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic properties. Incidence of gastrointestinal side effects associated with NSAIDs is relatively high and common. Gastrointestinal side effects of NSAIDs are related to various factors such as individual risk factors, the dose and the duration of use. NSAID use presents with a 2.5- to 5-fold increase in the risk of gastrointestinal tract (GI) complications[1]. These complications vary from abdominal discomfort to serious complications like ulceration, bleeding, perforation or obstruction[2]. Risk for adverse gastrointestinal events related to NSAID use are related to the age of the patient (> 60 years), presence of previous complicated/uncomplicated ulcer, use of multiple NSAIDs, dose of NSAIDs, type of drug, the presence of H pylori infection, concomitant use of corticosteroids and serious comorbid diseases[1,3]. Besides these, duration of the NSAID use, smoking and alcohol consumption have also been reported to increase the risk of NSAID complications, and the incidence of adverse events decrease with long-term use due to adaptation mechanisms[4,5].

The reports about NSAID use and related adverse events have so far involved therapeutic doses of NSAIDs. Therefore acute effects of short-term, especially high-dose NSAID and acetaminophen use have not been reported. This study was designed to investigate acute gastric injury and histological changes among patients who ingested high dose NSAID with suicidal intent. We evaluated the association of single high dose analgesic use with previous gastric complaints, smoking, food intake, drug dose, duration of exposure, co-existence of H pylori, and body position during intake (standing/supine) on the distribution of gastric lesions.

This is a prospective, randomized and controlled study. Fifty Patients admitted to the emergency unit after ingestion of high-dose analgesics with suicidal intent (group I) were included in the study. The control group consisted of 30 patients with or without mild dyspeptic complaints (group II). The patients in the study group were grouped according to the type of analgesic use: Of the 50 patients, 18 ingested only acetaminophen (group Ia), 32 have ingested only NSAIDs (group Ib) and in a subgroup of the NSAID ingesting group 10 ingested multiple types of NSAID simultaneously (group Ic). Exclusion criteria were: antacids, acid suppressants (H2-blocker, PPI), NSAIDs and steroid use with or without alcohol consumption, established gastric condition and treatment for gastric symptoms, systemic disease and homodynamic disorders and cognitive problems. The control group consisted of patients presenting with or without mild gastric complaints who had not been previously diagnosed with a gastric or any other disease, no history of alcohol use, and who had not used acid suppressants or NSAIDs within the last month. Exclusion of chronic or intermittent NSAIDs users enabled us to compare the endoscopic and histological assessed acute gastric damage with an almost healthy group. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee.

Demographic characteristics, smoking habits and history of gastric complaints during the last month were compared. The dose and type of drug used with suicidal intent was identified by examination of drug pack physically and information were obtained from the household. Information about time of the ingestion, type and amount of the drug, the occurrence of vomiting after intake, food intake and body position following the ingestion (standing/supine) and gastric lavage after the ingestion were recorded. The amount of ingested drug was standardized based on the pharmacological maximum recommended daily dose and scored in multiples (Table 1)[6].

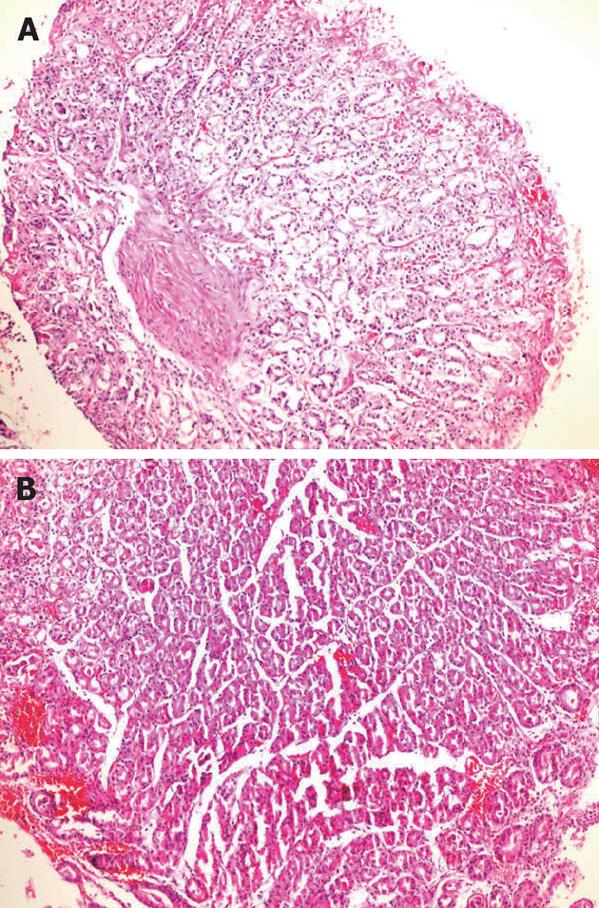

Within 24 h following drug ingestion, gastro-duodenoscopy was performed on the study and control groups. Endoscopic gastric findings were recorded by video endoscopy, and evaluated by a second endoscopy specialist according to the Lanza score (LS) (Table 2)[7,8]. Biopsies were obtained from the antrum for H pylori testing from all patients and from lesions if present. Biopsy specimens were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and with modified Giemsa for H pylori. In order to evaluate and quantify the histopathologic findings we have made a list of microscopic findings of NSAID-related acute erosive/hemorrhagic gastritis[9,10]. These findings were stratified into a three-scaled scoring algorithm according to the severity of the lesions which we present in Table 3 as biopsy score (BS).

Besides descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation, frequency), the Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, and Spearman’s Rank Correlation Test were used in the assessment of study results. Results were evaluated with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a significance level of P < 0.05.

Patients in group I [23.3 ± 7.5 years (range: 14-50)] were younger than those in group II [32.3 ± 7.6 years (range: 19-48)] (P = 0.001). There was no difference between the two groups in terms of smoking (P = 0.39) and H pylori positivity (P = 0.385) (Table 4). Patients in group Ia had ingested 1-5 times the maximum daily dose of acetaminophen, while those in group Ib had ingested 1.2-13.6 times the maximum daily dose of NSAIDs.

There was no significant difference between group I and group II with respect to gastric symptoms within the last month. Of the group I patients, 12% had nausea, 6% had mild heartburn, 4% had epigastric pain and 4% had hemathinized gastric fluid in nasogastric lavages during the emergency department examination. There was no difference in LS and BS among group I patients with or without gastric symptoms during last month.

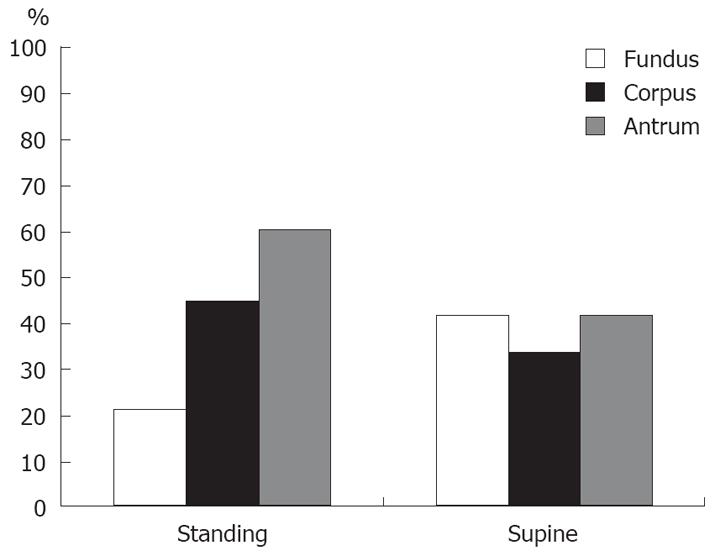

There was no difference between fundus, corpus, and antrum involvement of endoscopic lesions according to body position after drug intake (P > 0.05). Although there was no statistically significant difference in the distribution of gastric lesions in the fundus, corpus, or antrum according to body position after ingestion, the allocation of gastric lesions in the fundus were 21.1% in the standing and 41.7% in the supine positions, lesions in the antrum were 60.5% in the upright and 41.7% in the supine positions. Images of lesions according to the posture after the ingestion are demonstrated in Figure 1. Although there was no statistical significance, anatomical distribution of gastric lesions differed according to the body position after the ingestion (Figure 2).

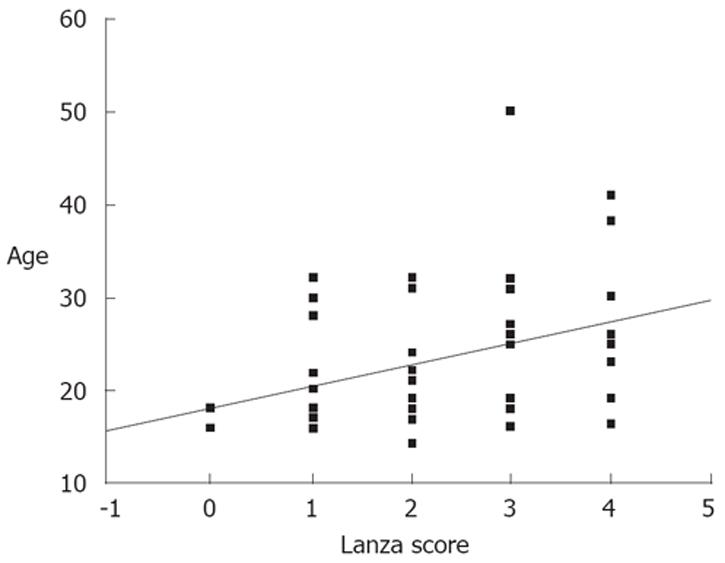

The LS of group I (2.3 ± 1.2) was higher than in group II (0.77 ± 0.6) (P < 0.01). The LS was positively correlated with age in group I (r = 0.39, P < 0.01), with a significant correlation at the 39.1% level. LS increased with age (Figure 3). Conversely, LS was not correlated with smoking habits, food intake, H pylori positivity and duration of exposure to the drugs (P > 0.05). Interestingly, the difference between the LS of patients who ingested only NSAIDs (group Ib) was higher but not significant compared to those who ingested only acetaminophen (group Ia) (P = 0.08). The LS of patients who ingested multiple types of NSAIDs was significantly higher than those who took a single type of NSAID (P < 0.01). There was a positive correlation between the total amount of ingested drugs and LS (r = 0.35, P < 0.05) which means that LS increased with increasing drug dose.

The BS of patients in group I (2.3 ± 0.8) was significantly higher than in patients of group II (1.47 ± 0.73) (P < 0.01). There was no correlation between BS and age, smoking habits, food intake, H pylori positivity or duration of drug exposure among group I (P > 0.05). The BS of group Ib patients (2.58 ± 0.70) was higher than in patients in group Ia (1.94 ± 0.87) (P < 0.05). The BS of patients who ingested only NSAIDs was higher than in those who ingested only acetaminophen (P < 0.05). The BS of patients who took multi-agent NSAIDs and of those who took single-agent NSAIDs were similar (P > 0.05). There was no significant correlation between the total amount of ingested drug and BS (P > 0.05).

Besides personal risk factors, the type and the dose of NSAIDs, duration of exposure to the drug and concomitant use of other drugs play an important role on NSAID-related GI side effects[11]. In our study, we observed a positive correlation between endoscopically observed gastric injury and age, although none of our patients were in the age group (> 60 years) established as an individual risk factor. The gastric effects of NSAIDs vary according to their acute or chronic use. Short-term studies have reported that gastroduodenal mucosal injury is dose-dependent. Acute injury on the gastric superficial epithelium occurs within minutes, whereas subepithelial hemorrhage and erosions occur within hours[12,13]. Asymptomatic endoscopically observed lesions are submucosal hemorrhage, erosions, and ulceration. Intramucosal hemorrhage, petechia, and mucosal erosions have been observed endoscopically with short-term usage. Superficial ulceration typically appears within 1 wk[11]. Following single-dose (650-1300 mg) aspirin intake, gastric lesions occur with a 100% certainty[12]. This gastric mucosal injury has been reported to develop rapidly, within 24 h of ASA intake, erosions have been observed within the first 24 h, and maximal damage appeared within 3 to 7 d[8,14,15]. In our endoscopic evaluation within the first 24 h, hemorrhagic foci, erosions and marked gastric ulceration were observed. There were acute findings in the histomorphological evaluation such as congestion of the superficial lamina propria, edema, extravasated erythrocyte and fibrin aggregates within two patients whose LS was 0.

The gastric effects of long-term NSAID use are diverse. Gastric and duodenal mucosal erosions and gastroduodenal ulcers, hemorrhage, perforation and even fatality due to complications of ulceration can occur[12,16]. In long-term NSAID users, gastric injury is more likely to be more severe and has a higher possibility to be localized in the antrum than the corpus[13,17]. Lesions situated in the antrum might penetrate into the submucosa and tend to be wider in size (> 6 mm)[13,18]. Ulcers are most commonly localized in the stomach and are diffused, multiple and painless[4]. Many patients who show mucosal damage in the form of ulceration have no or mild symptoms, while many cases without visible mucosal damage present with indigestion, abdominal pain, distension and flatulence[8,16,19]. Sudden-onset GI hemorrhage or silent perforation has also been reported following ingestion of NSAIDs[8]. In our study of acute high dose use, physical examination and symptom inquiry did not reveal apparent differences and clinical presentation and endoscopic findings were not correlated as in the chronic NSAID users. None of the patients were admitted for gastric symptoms, they were rather admitted for the long term toxicity concerns. One patient with marked ulcerations had mild epigastric pain. Abdominal palpation was normal for two patients who had extensive superficial ulcerations and hemathinized fluid in nasogastric lavage.

Various studies have reported an increase in the risk of gastrointestinal toxicity with short-term NSAIDs use, and demonstrated that the first month of treatment presents the largest risk, while the risk thereafter decreases with chronic use[4]. A meta-analysis of 16 studies by Gabriel et al reported an 8-fold increase in the NSAID-related gastrointestinal risk within the first 1 mo, a 3.3-fold increase within 1-3 mo and 1.9-fold increase for longer than 3 mo of use[5]. LS was 4 in 20% of our cases, which present an example for risk of high-dose NSAIDs in the short-term use. This high percentage may be interpreted as the added ulceration effect of acute local toxic damage without a period of adaptation, thus these patients had multiple and large superficial ulcerations and marked hemorrhagic foci.

Endoscopic evaluations demonstrated that superficial lesions develop acutely, within minutes, and that topical factors prevail in the development of lesions. Acute lesions involve only the mucosa, are small in size, and are more prevalent in the fundus than in the antrum[13,18]. NSAID-related ulceration is most often localized in the greater curvature of the antrum. In adults, in the normal upright position, this region is susceptible to external factors, indicating that this type of ulceration (sump-ulcer) is related to the direct ingestion of corrosive substances[13]. A study on this subject reported more histological damage in the antrum than in the corpus[15]. In an endoscopic evaluation in 6 healthy dogs following administration of carprofen (4 mg/kg) and deracoxib (4 mg/kg), involvement of the fundus, antrum and lesser curvature was reported to deteriorate on the second day of treatment and heal on the fifth day[20]. Since early topical consequences are in the forefront in our cases, gastric lesion involvement in the fundus was observed in 41.7% of the patients who were in the supine position following drug intake, and in the antrum in 60.5% of the patients who remained standing, albeit without statistical significance. Considering that local damage is greater than systemic effects, this may account for the lack of significance of high-dose drug use with more intense topical exposure and localization.

Subsequent doses have been determined to increase the frequency, but not the severity of lesions[14,20]. The damage was greatest on the third day of continuous use, and endoscopic damage was lesser on the seventh day than the first day. Adaptation occurred at around the third day, and was found to be associated with increasing healing processes[14]. Endoscopic gastric damage is primarily dose-related and occurs even in anti-inflammatory doses of NSAIDs. In a study with 1 064 healthy volunteers, 6.7% of the subjects developed ulcerations after a 7-d course of anti-inflammatory dose[19]. Adaptation and resolution occur more slowly with high doses and more rapidly with low doses, and discontinuation accelerates the healing process[15]. We have preferred not to have a chronic NSAID user control group, so that we could demonstrate gastric damage in acute NSAID use.

Bergmann et al[21] administered single-dose ketoprofen (25 mg), ibuprofen (200 mg) or aspirin (500 mg) to 12 healthy subjects with empty stomach and found that lesions were similar with ketoprofen and ibuprofen using the LS and they were less local toxic compared to aspirin. Previous publications support the finding of the local damaging effect of short-term, single-dose use of NSAIDs[15]. In our study, the total amount of drug taken was found to be correlated with LS. We found a correlation between the total amount of drug taken and the severity of endoscopic findings. Also, multiple types of NSAID users had more endoscopic gastric damage than acetaminophen only or single NSAID users.

In a study that investigated damage on the gastric mucosa 10 and 60 min after the direct administration of 2 g acetaminophen in 100 mL saline solution, 10 min after administration cellular damage was seen in 3%-5% in the study group and 1%-7% in the control group. Microscopic evaluation showed focal cellular disruption and erythrocyte infiltration. Electron microscopy revealed minimal loss in the cellular apex, but no erosion. The corresponding findings with aspirin are quite different. A 2 g dose of acetaminophen caused minimal mucosal damage[22]. After a 7d continuous treatment on 7 healthy volunteers, aspirin and acetaminophen (1.95 g/d or 2.6 g/d) plus aspirin (1.95 g vs 3.9 g) on a full stomach caused escalating mucosal damage with increasing doses in the group that received aspirin. However, the addition of acetaminophen to the aspirin regimen did not cause any deterioration of gastric damage. All doses were received on a full stomach[23]. In the study group, food intake before ingestion of analgesics had no effect on LS or BS. Patients who took acetaminophen had ingested single doses of 4000 to 20 000 mg, and their endoscopic evaluations revealed LS of 0 to 4. The LS of two patients who took 10 000 mg acetaminophen was 0 and 4, respectively. The unsteadiness of the BS might be due to the non-uniformity of gastric histomorphologic findings. In this study, the determination of endoscopic damage among patients who ingested higher doses of acetaminophen compared to previous studies[22,23] indicate that high-dose acetaminophen use may cause damage, however the damage and dose relationship suggests that factors other than dose also play a role.

Chemical gastropathy may present with separate or concurrent nonspecific histopathologic lesions of various degrees and proportions, and no correlation between histological findings and clinical symptoms, particularly the risk of bleeding, has been documented in gastropathy[24]. Following aspirin ingestion, the inconsistency of biopsy results during histological evaluations may reflect sampling errors, or aspirin-related changes may be unpredictable. None of the biopsies taken from normal-appearing mucosal tissue following aspirin intake yielded normal results. Visible damage may somewhat intensify after the second and third doses, but the extent of damage does not increase after a couple of doses, and may even start to diminish. Although mucosal appearance normalizes, gastric microhemorrhages do not cease to occur during aspirin use[15]. Histomorphological evaluation is significant in such cases[9]. In this study, BS was not correlated with the total amount of drug taken or the use of multiple NSAIDs. However, histological gastric damage was more extensive in patients who ingested NSAIDs compared to those who ingested acetaminophen only. There were no marked histomorphologic differences between biopsy evaluations of acetaminophen and NSAID patients. Nonetheless, the biopsies of all patients who took only acetaminophen revealed acute gastric damage, and six patients with a BS over 3 had ingested 6000 mg (n = 1) or 10 000 mg (n = 5) acetaminophen. The BS and LS of acetaminophen only patients did not correlate to the acetaminophen dose increments (Figure 4). Even the patient with a LS of 0 had findings of erosive gastritis in the histomorphologic evaluation. Also, all patients had more bleeding during endoscopic biopsy procedures compared to routine procedure or chronic NSAID users.

H pylori infection and NSAID-related gastric mucosal damage occur through different pathways and separate mechanisms[16]. Foveolar hyperplasia, edema and vascular ectasia are more extensive in NSAID-related gastritis compared with H pylori gastritis[13,17]. Gastric damage related to aspirin use was found to be more limited in patients with H pylori eradication, thus indicating that H pylori may enhance NSAID-induced gastric damage[25]. It was also reported that ulcer bleeding was more prevalent in patients with H pylori infections[26]. Conversely, certain studies have reported that positivity or negativity of H pylori in NSAID users made no significant difference[27,28]. In our study, H pylori positivity was not related to significant changes in LS or BS in patients who had taken acetaminophen and NSAIDs.

Acute gastric damage of varying degrees occurs in subjects who ingest high doses of NSAIDs and acetaminophen with suicidal intent. The degree of endoscopic acute lesions in high-dose analgesic use also increases with age, total drug dose, concurrent use of multiple types of NSAIDs. We found the BS of patients who ingested only high-dose NSAIDs to be higher than in those who took acetaminophen, while there was no significant difference between gastric lesions. The lack of statistical significance between the LSs of patients who ingested NSAIDs and those who took only acetaminophen is remarkable in terms of the gastric effects of high-dose acetaminophen. It may be concluded that, contrary to current convictions, high-dose acetaminophen may also cause endoscopic acute gastric damage. Body position following intake influences the localization of endoscopic lesions. H pylori positivity was not determined as a factor that may affect NSAID- and acetaminophen-related acute gastric damage endoscopically or histopathologically.

In patients in a stable condition, we recommend endoscopy within the first 24 h for the determination of gastric injury and for treatment maintenance in patients who have ingested high-dose analgesics with suicidal intent.

Analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen, are commonly used for the relief of fever, headaches, and other minor aches and pains. The gastrointestinal side effects of NSAIDs are well documented and acetaminophen is accepted to be a safe drug for the gastrointestinal system. Acute effects of short-term, especially high-dose NSAID and acetaminophen use have not been studied adequately.

Acute gastric injury due to high dose analgesic use. Gastrointestinal safety of acetaminophen. Scoring the histological severity of the gastritis.

This paper is one of the first to document the endoscopic acute gastric damage caused by acute high-dose acetaminophen.

The results of the present paper may be useful in evaluating the gastrointestinal complications of acute high dose analgesic use. Contrary to current convictions, high-dose acetaminophen, as well as NSAIDs, may also cause endoscopic acute gastric damage. Therefore physicians should be alert at evaluating the gastrointestinal complaints of acetaminophen users as well. The study suggests that clinicians might as well plan endoscopic evaluation in patients who ingested high-dose analgesics with suicidal intent.

The importance of the research and the significance of the research contents are significant because as it is mentioned in the manuscript there is actually not much information about acute high-dose acetaminophen causing endoscopic acute gastric damage. The manuscript is very readable. Methods are appropriate and detailed description is provided for any modified or novel methods to allow other investigators to reproduce or validate.

Peer reviewer: Mark S Pearce, PhD, Paediatric and Lifecourse Epidemiology Research Group, School of Clinical Medical Sciences, University of Newcastle, Sir James Spence Institute, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 4LP, United Kingdom

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Kremer M E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Lanas A, Hirschowitz BI. Toxicity of NSAIDs in the stomach and duodenum. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:375-381. |

| 2. | Akarca US. Gastrointestinal effects of selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:1779-1793. |

| 3. | Lanas A. Prevention and treatment of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal injury. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:147-156. |

| 4. | Sung J, Russell RI, Nyeomans , Chan FK, Chen S, Fock K, Goh KL, Kullavanijaya P, Kimura K, Lau C. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug toxicity in the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15 Suppl:G58-G68. |

| 5. | Gabriel SE, Jaakkimainen L, Bombardier C. Risk for serious gastrointestinal complications related to use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:787-796. |

| 6. | Burke A, Smyth E, FitzGerald GA. Analgesic-antipyretic agent; Pharmacotherapy of gout. Goodman & Gillman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 2006; 671-715. |

| 7. | Lanza FL, Royer GL Jr, Nelson RS, Rack MF, Seckman CC. Ethanol, aspirin, ibuprofen, and the gastroduodenal mucosa: an endoscopic assessment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:767-769. |

| 8. | Lanza FL. Endoscopic studies of gastric and duodenal injury after the use of ibuprofen, aspirin, and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Am J Med. 1984;77:19-24. |

| 9. | Noffsinger AE, Stemmermann GN, Lantz PE, Isaacson PG. The nonneoplastic stomach. Gastrointestinal Pathology: An Atlas and Text, 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2008; 135-231. |

| 10. | Bhattacharya B. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Stomach. Gastrointestinal and Liver Pathology (A Volume in the Series Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology). London: Churchill-Livingstone 2005; 66-125. |

| 11. | Aalykke C, Lauritsen K. Epidemiology of NSAID-related gastroduodenal mucosal injury. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;15:705-722. |

| 12. | Lichtenstein DR, Syngal S, Wolfe MM. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the gastrointestinal tract. The double-edged sword. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:5-18. |

| 13. | Graham DY. Peptic diseases of the stomach and duodenum. Gastroenterologic Endoscopy. Philadelphia: Saunders 2000; 615-641. |

| 14. | Graham DY, Smith JL, Dobbs SM. Gastric adaptation occurs with aspirin administration in man. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:1-6. |

| 15. | Graham DY, Smith JL, Spjut HJ, Torres E. Gastric adaptation. Studies in humans during continuous aspirin administration. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:327-333. |

| 16. | Peura DA. Prevention of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastrointestinal symptoms and ulcer complications. Am J Med. 2004;117 Suppl 5A:63S-71S. |

| 17. | Haber MM, Lopez I. Gastric histologic findings in patients with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastric ulcer. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:592-598. |

| 18. | Soll AH, Weinstein WM, Kurata J, McCarthy D. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and peptic ulcer disease. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:307-319. |

| 19. | Lanza FL. A review of gastric ulcer and gastroduodenal injury in normal volunteers receiving aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;163:24-31. |

| 20. | Dowers KL, Uhrig SR, Mama KR, Gaynor JS, Hellyer PW. Effect of short-term sequential administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the stomach and proximal portion of the duodenum in healthy dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2006;67:1794-1801. |

| 21. | Bergmann JF, Chassany O, Genève J, Abiteboul M, Caulin C, Segrestaa JM. Endoscopic evaluation of the effect of ketoprofen, ibuprofen and aspirin on the gastroduodenal mucosa. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;42:685-687. |

| 22. | Ivey RJ, Silvoso GR, Krause WJ. Effect of paracetamol on gastric mucosa. Br Med J. 1978;1:1586-1588. |

| 23. | Graham DY, Smith JL. Effects of aspirin and an aspirin-acetaminophen combination on the gastric mucosa in normal subjects. A double-blind endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1922-1925. |

| 24. | Genta RM. Differential diagnosis of reactive gastropathy. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2005;22:273-283. |

| 25. | Giral A, Ozdogan O, Celikel CA, Tozun N, Ulusoy NB, Kalayci C. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on anti-thrombotic dose aspirin-induced gastroduodenal mucosal injury. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:773-777. |

| 26. | Adamopoulos A, Efstathiou S, Tsioulos D, Tsami A, Mitromaras A, Mountokalakis T. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: comparison between recent users and nonusers of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Endoscopy. 2003;35:327-332. |

| 27. | Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Valerio G. The effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on NSAID-related gastroduodenal damage in the elderly. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:951-956. |

| 28. | Niv Y, Battler A, Abuksis G, Gal E, Sapoznikov B, Vilkin A. Endoscopy in asymptomatic minidose aspirin consumers. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:78-80. |