Published online Nov 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6648

Revised: October 31, 2008

Accepted: November 7, 2008

Published online: November 21, 2008

AIM: To distinguish anastomotic from parenchymal leakage at duct-to-mucosa reconstruction of the pancreatic remnant.

METHODS: We reviewed the charts of 68 pancreaticod-uodenectomies performed between 5/2000 and 12/2005 with end-to-side duct-to-mucosa pancreatojejunostomy (PJ). The results of pancreatography, as well as peripancreatic drain volumes, and amylase levels were analyzed.

RESULTS: Of 68 pancreatojejunostomies, 48 had no leak by pancreatography and had low-drain amylase (normal); eight had no pancreatographic leak but had elevated drain amylase (parenchymal leak); and 12 had pancreatographic leak and elevated drain amylase (anastomotic leak). Although drain volumes in the parenchymal leak group were significantly elevated at postoperative day (POD) 4, no difference was found at POD 7. Drain amylase level was not significantly different at POD 4. In contrast, at POD 7, the anastomotic-leak group had significantly elevated drain amylase level compared with normal and parenchymal-leak groups (14158 ± 24083 IU/L vs 89 ± 139 IU/L and 1707 ± 1515 IU/L, respectively, P = 0.012).

CONCLUSION: For pancreatic remnant reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy, a combination of pancreatogram and peripancreatic drain amylase levels can be used to distinguish between parenchymal and anastomotic leakage at pancreatic remnant reconstruction.

- Citation: Nguyen JH. Distinguishing between parenchymal and anastomotic leakage at duct-to-mucosa pancreatic reconstruction in pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(43): 6648-6654

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i43/6648.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6648

| Normal | Parenchymal leak | Anastomotic leak | |

| n | 48 | 8 | 12 |

| Age (yr1) | 67.5 (29-81) | 56.0 (51-79) | 65.5 (51-82) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Ductal adenocarcinoma | 28 | 1 | 4 |

| Duodenal adenomas | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Neuroendocrine | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| FAP | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cystadenoma | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Benign stricture | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| IPMN | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Others | 7 | 1 | 1 |

| RBC transfused (U1) | 2 (0-39) | 2 (0-18) | 2.5 (0-88) |

| OR time (h1) | 5.94 (4.18-11.04) | 5.55 (3.40-14.55) | 5.04 (4.93-10.65) |

| Biliary leak | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastric leak | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Intraabdominal abscess | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Normal | Anastomotic leakage | Parenchymal leakage | |

| Pancreatography | No extravasation | Extravasation present | Normal |

| Peripancreatic drain | Normal | Elevated | Elevated |

| Occurrence, n (%) | 48 (72.7) | 8 (12.1) | 12 (18.2) |

Pancreaticoduodenectomy remains the surgical resection of choice for cancer of the head of the pancreas. Surgical techniques for reconstructing the pancreatic remnant after pancreaticoduodenectomy include end-to-end pancreatojejunostomy (PJ) with invagination, end-to-side PJ with[1,2] or without pancreas invagination[3], pancreatic duct invagination[4], pancreaticocutaneous fistula[5], and external drainage of the pancreatic duct without pancreaticoenteric reconstruction[6]. However, pancreatic leakage remains a significant complication, occurring in 0%-37% of cases[1,7,8]. An unrecognized leak at the PJ anastomosis can result in lethal complications, in particular, intra-abdominal abscess and hemorrhage[9-12].

Pancreatic leaks have traditionally been defined by amylase levels measured in the peripancreatic fluid obtained by placing a drain immediately around the PJ anastomosis[13]. However, pancreatic juice can originate either from the main pancreatic duct or from the cut surface of the pancreatic parenchyma. Thus, an elevated level of amylase in the fluid obtained from the peripancreatic drain suggesting pancreatic leakage does not indicate whether the leak is at the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis (an anastomotic leak) or from the resection parenchyma surface (a parenchymal leak). The existence of parenchymal leakage was previously shown to be from an accessory small duct in the parenchyma, separate from the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis[14]. However, it is difficult to distinguish between an anastomotic and a parenchymal pancreatic leak at end-to-side duct-to-mucosa PJ reconstruction. The aim of this study was to assess the PJ following pancreaticoduodenectomy to characterize the nature of PJ leaks.

In the cases studied, the pancreatic remnant following pancreaticoduodenectomy was reconstructed with end-to-side duct-to-mucosa PJ, as described previously[15]. The PJ anastomosis was critically evaluated postoperatively with pancreatography via an externalized pancreatic stent placed at the time of surgery. We found that duct-to-mucosa anastomotic leakage could be distinguished from parenchymal leakage at the PJ reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy by using the combined radiographic findings on pancreatography and amylase levels in the peripancreatic drain fluid.

Medical records of patients who underwent abdominal exploration for pancreatic mass between May 2000 and December 2005 were reviewed. The review of patient records was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida. Classical pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed as previously described[3]. The pancreas was divided left of the portal vein[14]. The pancreatic remnant was reconstructed with end-to-side duct-to-mucosa PJ using 6-0 PDS sutures as previously described[15]. The anterior and posterior parenchyma-to-serosa layers were completed with interrupted 3-0 silks. End-to-side choledochojejunostomy and antecolic gastrojejunostomy were performed.

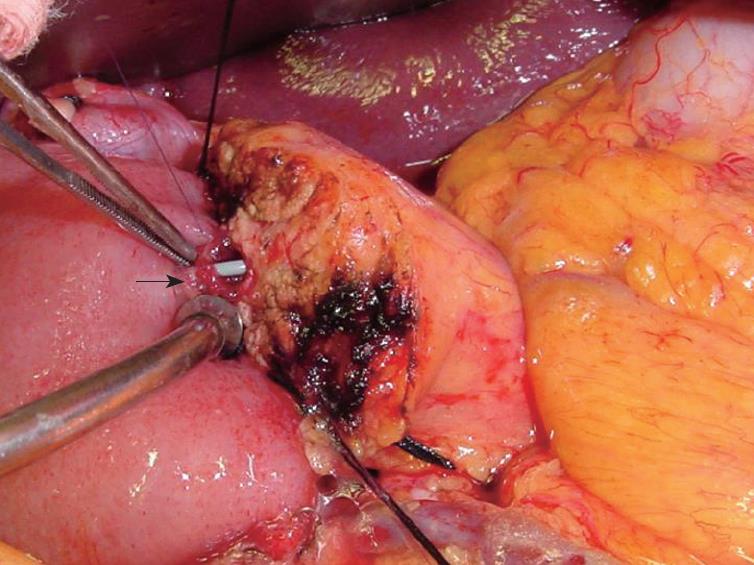

Across the PJ anastomosis, a stent was placed through the jejunal limb as shown in Figure 1, similar to previous reports[11,16-18]. The exit site of the stent at the jejunal serosa was secured with a Witzel’s tunnel using 3-0 silks and a 5-0 Vicryl™ suture. A stent was similarly placed across the biliary reconstruction. This stenting technique was adopted from the same technique used routinely in liver transplantation at our center since 1998. A 6-mm round Blake drain was placed beneath the PJ reconstruction and brought through the left abdominal wall. A nasogastric tube was positioned just above the gastrojejunal anastomosis. The biliary and pancreatic stents were brought through the right abdominal wall.

On postoperative day (POD) 4, a pancreatogram and a cholangiogram were performed by interventional radiologists, who gently injected 1 to 3 mL of water-soluble contrast through the respective externalized pancreatic and biliary stents. The biliary and pancreatic anastomoses were evaluated by fluoroscopy. Serum and drain amylase levels were measured. Drain amylase level was considered significant when it was at least 3 times the upper normal level of serum amylase[13]. After several days of oral food intake, normal pancreatogram results, and low or normal drain amylase level, the drain was removed and the patient was discharged. The patient returned to the outpatient clinic on POD 28, and a repeat pancreatogram and cholangiogram were performed. If there was no evidence of leakage at either anastomosis, the stents were removed.

When a leak was identified at the PJ anastomosis, the peripancreatic drain was maintained until the leak resolved. Patients were started on a fat-free diet and subcutaneous octreotide (Novartis, USA). A pancreatogram was repeated weekly until the PJ leak resolved. Once the leak was resolved, as confirmed by repeat pancreatography, the stents and drain were removed and a regular diet was begun. Surgical re-exploration was performed when peripancreatic abscess was not amenable to percutaneous drainage, and/or when a widely disrupted PJ anastomosis was visualized on pancreatogram.

From May 2000 to December 2005, of the 105 cases of surgical exploration for pancreatic mass, there were seven palliative bypasses due to unresectable metastatic disease. Seventeen cases had distal pancreatectomy, two transduodenal ampullectomy, 11 pancreaticoduodenectomy with total pancreatectomy, and 66 classical pancreaticoduodenectomy. The demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

Of the 66 patients who had pancreaticoduo-denectomy, two required revision of the PJ anastomosis. One patient had afferent loop obstruction and necrosis due to radiation-induced stricture 2 years after the pancreaticoduodenectomy. The afferent loop was revised with a new end-to-side duct-to-mucosa PJ anastomosis and biliojejunostomy. The other patient developed a large peripancreatic abscess and PJ anastomotic leak that did not resolve with conservative management. After re-exploration, the PJ was reconstructed. Since these revisions required complete reconstruction of the pancreatic remnant, the two revised PJ anastomoses were considered independent anastomoses. The outcomes in these 68 PJ anastomoses formed the basis of this study.

The integrity of the PJ anastomosis was visualized by fluoroscopy. Of the 68 PJ anastomoses, eight pancreatic anastomotic stents migrated out of the pancreatic remnant. Of those eight, three had successful reflux of the injected contrast into the pancreatic ductal system, demonstrating no leak. In the remaining five, there was no reflux of contrast into the pancreatic ductal system, nor was extravasation seen at the PJ anastomosis. Of the 60 cases with successful pancreatograms, 48 showed no PJ extravasation, i.e., no anastomotic leak, and 12 showed the presence of an anastomotic leak.

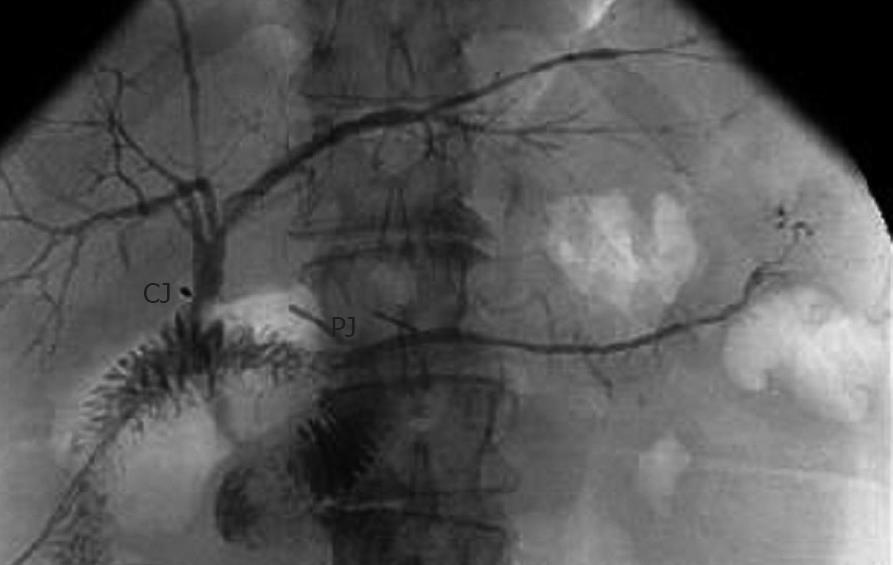

A typical pancreatogram and cholangiogram are shown in Figure 2, demonstrating intact PJ and choledochojejunostomy anastomoses. Three patients had mild abdominal discomfort during the pancreatogram injections without increased serum amylase levels. The discomfort resolved spontaneously within a few hours, and there were no other complications directly associated with the pancreatic stents and pancreatograms. Although not shown, in all cases serum amylase levels did not change the day before or the day after the pancreatograms. Serum amylase levels were normal by POD 4.

As shown in Table 2, we noted three outcomes at the PJ anastomosis after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

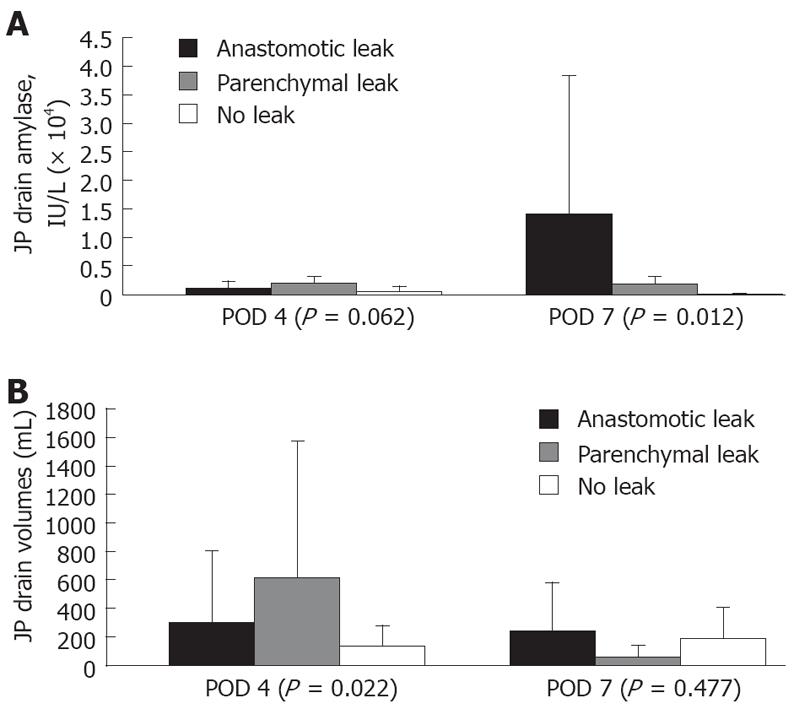

Normal: This pattern was associated with a normal pancreatogram, demonstrating an intact PJ anastomosis and low amylase levels from the drain. Forty-eight cases had this normal pattern, including both PJ revisions. The eight cases in which the pancreatic stent dislodged into the lumen of the jejunum had normal drain amylase levels and were included in this normal group. As shown in Figure 3, the peripancreatic PJ drain amylase levels and volumes in the normal group were lower than those in patients with a pancreatic leakage.

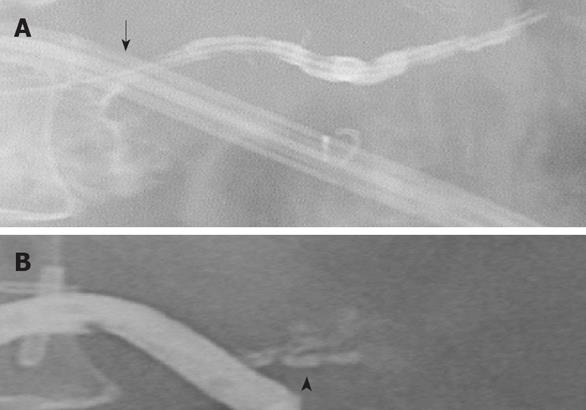

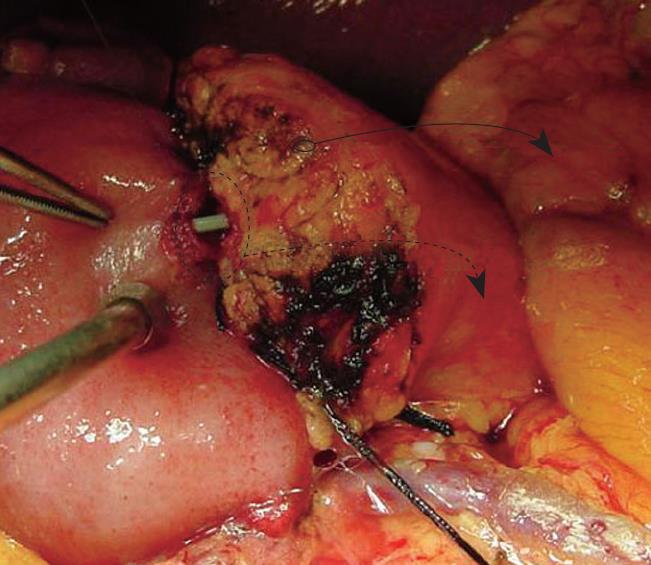

Parenchymal leak: This pattern was recognized when there was a normal PJ anastomosis without contrast extravasation on pancreatograms but with persistently high amylase levels in the peripancreatic drains. Eight patients had this pattern. On POD 4 and 7, drain amylase levels in the parenchymal leak group were elevated at 1885 ± 1129 IU/L vs 428 ± 1063 IU/L (P = 0.062) and 1707 ± 151 IU/L vs 89 ± 139 IU/L (P = 0.012), respectively. The drain amylase levels became normal between POD 18 and POD 101 after parenchymal pancreatic leak. Most parenchymal leaks resolved by POD 48. In one patient, a repeat study showed the presence of a parenchymal side-branch duct that appeared to be responsible for the high amylase levels detected in the drain (Figure 4). Tessel fibrin sealant was injected, and the drain was removed. Follow-up study showed no fluid collection at the immediate or surrounding areas of the pancreatic anastomosis, suggesting complete resolution of the pancreatic leakage.

Anastomotic leak: This pattern was defined by the presence of contrast extravasation at the duct-to-mucosa PJ anastomosis on pancreatogram. These pancreatographic findings were similar to those in a previous report[11]. There were 12 anastomotic leaks. Eleven of the 12 PJ leaks were diagnosed on POD 7 via pancreatogram. The highest drain amylase level was 90 000 IU/L. Most elevated drain amylase levels occurred between POD 5 and POD 9, when the anastomotic leaks were also documented radiographically. In fact, the drain amylase levels in this group were significantly elevated at 14158 ± 24083 IU/L vs 1707 ± 1515 IU/L and 89 ± 139 IU/L for the parenchymal leak and normal groups at POD 7, respectively (Figure 3A). There was no significant difference among the three groups at POD 4.

The volumes of the peripancreatic drains did not correlate with the leaks seen on pancreatography or the drain amylase levels. As shown in Figure 3B, the volumes of the peripancreatic drains in the anastomotic group were not different from the other two groups at POD 7, although the parenchymal leak group had significantly higher drain volumes at POD 4.

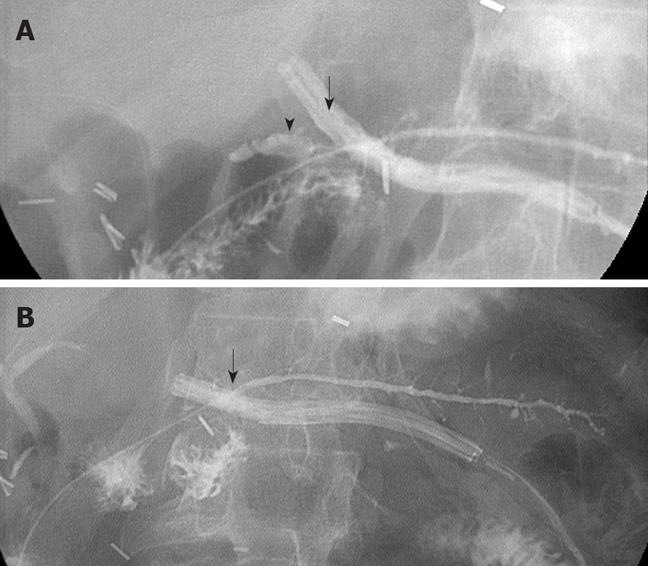

The results of serial pancreatograms provide insight into the natural progression of anastomotic leaks at an end-to-side duct-to-mucosa anastomosis after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Figure 5 shows an example of an anastomotic leak at the duct-to-mucosa PJ reconstruction. The first pancreatogram, done on POD 4, did not show a leak. With a high level of drain amylase on POD 7, repeat pancreatogram showed a significant leak at the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis with extravasation into the surrounding space (Figure 5A). Subsequent pancreatograms showed gradual and complete resolution of the PJ leak (Figure 5B).

Of the 12 pancreatic anastomotic leaks, eight showed radiographic evidence of resolution in conjunction with drain amylase levels tapering toward normal levels by POD 42. In two cases, the anastomotic leak resolved by POD 123 and 189. None of the pancreatic anastomotic leaks resolved without therapeutic intervention, such as replacement of the peripancreatic drains if the primary drains were displaced and/or replacement of pancreatic anastomotic stents if they became dislodged from the lumen of the pancreatic remnant. One patient had a small leak at the PJ anastomosis on pancreatogram on POD 4. The drain amylase level was 1184 IU/L on POD 2. No subsequent amylase levels were obtained. This patient had portal vein thrombosis, intracranial infarction, and multiorgan failure, and died on POD 31. Autopsy did not show a pancreatic leak. The pancreatic leak had resolved and was not the cause of death.

Among the 12 patients with pancreatic anastomotic leaks, only one required surgical re-exploration due to refractory abscess. On the day of surgical re-exploration at POD 37, the drain amylase level was 1919 IU/L. Yet, the pancreatogram showed a large leak at the PJ anastomosis. During re-exploration, the PJ anastomosis was found to be almost completely disrupted. A new end-to-side duct-to-mucosa PJ anastomosis was performed. No PJ anastomotic leak recurred.

Pancreatic leakage results in major morbidity and mortality after pancreaticoduodenectomy. In this study, we critically examined the integrity of the duct-to-mucosa PJ anastomosis. By analyzing both pancreatography findings and drain amylase levels, we found a way to distinguish parenchymal from anastomotic leakage at the PJ anastomosis. Of the 20 pancreatic leaks at the PJ anastomosis, eight (40%) originated from the parenchymal or small side branch duct, and 12 (60%) originated from the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis. These findings suggest that in duct-to-mucosa PJ anastomosis, parenchymal leakage is almost as common as anastomotic leakage.

In parenchymal pancreatic leakage, pancreatography consistently showed no extravasation at the pancreatic anastomosis. Nevertheless, drain amylase levels were elevated. In one of the eight cases, a small side-branch ductal leak was found along the parenchymal surface of the pancreatic remnant. Although only one case, it represented a potential and likely source of pancreatic leakage in the absence of true anastomotic leakage. It also appears that these parenchymal non-anastomotic leaks tend to resolve spontaneously. These findings are consistent with a previous report demonstrating that most pancreatic leaks do not require surgical exploration[19]. In another case, a 1.5-mm side branch in the cut surface of the pancreatic remnant was observed intraoperatively. This side branch duct was approximate 1 cm from the main pancreatic duct and was only 1 cm in length. Fibrin sealant was injected, and the PJ anastomosis was completed in routine fashion. Postoperatively, there was no evidence of pancreatic leakage.

In the cases studied, pancreatic anastomotic leakage was confirmed by the presence of contrast extravasation at the duct-to-mucosa anastomosis on pancreatogram. The levels of drain amylase continued to increase until the leak started to resolve. In contrast to parenchymal leaks, anastomotic leaks tend not to resolve spontaneously. Appropriate intervention, either replacement of the indwelling anastomotic stent or surgical exploration for large anastomotic disruption, is required. In this series, after re-establishing the dislodged pancreatic stents by interventional radiology, the two anastomotic leaks resolved at 123 and 189 d, compared with 14 wk (or 98 d) in a previous report[20]. Eight of the 12 PJ anastomotic leaks resolved within 10 wk in this series, with a range of 15 to 76 d. The patients whose PJ leak took the longest to heal had a dislodged pancreatic anastomotic stent. Once the percutaneous stent was successfully replaced, the PJ leak healed within 3 wk. These findings support the concept that mucosa-to-ductal epithelial healing is probably promoted by stent placement across the PJ anastomosis[21]. In addition, the externalized stent allows for continuous external drainage of luminal pancreatic juice and promotes healing of the PJ anastomosis. However, our results do not directly suggest that a pancreatic stent is required. Pancreatic stents are not commonly used, therefore, PJ anastomoses might heal without a stent. Rather, the use of pancreatic stents in this study may provide a means to understand the exact source and nature of pancreatic leaks after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

We have found that most pancreatic leaks can be managed conservatively, which is consistent with the findings of others[16,19,20]. The indications for surgical re-exploration are intra-abdominal refractory abscess or hemorrhage. In this series, no hemorrhage occurred. However, hemorrhage secondary to a pancreatic leak remains a lethal complication. Accurate diagnosis of a pancreatic anastomotic leak is thus essential. In our series, only one of the 12 anastomotic leaks needed surgical correction.

Other studies have indicated different factors related to increased risk of a pancreatic leak after pancreatectomy, such as soft pancreatic texture and small duct size[4,11,22]. It seems probable that pancreatic leaks may result from parenchymal tears by sutures, resulting in a leak via a parenchymal side-branch duct. However, without objective evidence, such as a pancreatogram, it would be impossible to define the exact nature of the leak.

Although they did not demonstrate their findings radiographically, Matsusue and colleagues suggested a similar distinction for peripancreatic sepsis as the result of parenchymal or non-anastomotic seepage of pancreatic juice versus a pancreatic fistula from pancreatic anastomotic failure[19]. Our findings for parenchymal leakage correspond to their description of peripancreatic sepsis, and our anastomotic leak corresponds to their pancreatic fistula. Furthermore, without radiographic evidence, a pancreatic leak can be classified by using the volume and amylase level of the fluid in the peripancreatic drain and the requirement for therapeutic intervention[13]. However, the most important difference lies within our capability to directly visualize radiographically the pancreatic anastomosis. Together, the results from drain amylase levels and the pancreatogram can clearly distinguish a true anastomotic leak from a parenchymal non-anastomotic leak as illustrated in Figure 6. These findings are limited, however, by the small number of parenchymal leaks (n = 8). Larger numbers in future prospective studies will be required to further understand the exact nature of pancreatic leaks at PJ reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

One can argue for the need for pancreatic and biliary stenting. From our experience with liver transplantation, biliary stenting is not uniformly used. This is because the placement of the biliary tube is usually performed via a T-tube through a surgically created opening in the common bile duct, which leads to persistent biliary leakage after removal of the biliary T-tube. In contrast, since the beginning of the liver transplantation program at our center in 1998, we insert the biliary tube via the donor cystic duct and secure it with a rubber band. For bilioenteric anastomosis, the biliary tube is inserted through the jejunal limb and secured with a Witzel’s tunnel. The biliary tube and the pancreatic stent are each kept in place with a 5-O Vicryl™ suture, which will dissolve by 4 wk, allowing for safe removal of the biliary tube at 28 d. When this method is used, biliary stenting and pancreatic stenting have been safe. No complications have occurred as a result of a stent.

Although it was not a stated aim of this study, we have found that the technique of placing an externalized PJ anastomotic stent at the time of pancreaticoduodenectomy is helpful for postoperative management. Such stenting allows access to the pancreatic ductal system for assessing anastomotic integrity by pancreatography and control of drainage, should a leak be found. None of our patients with leaks had significant hemorrhage, peripancreatic inflammation, or completion pancreatectomy[10]. In addition, the presence of this stent allows ongoing assessment of the anastomosis and facilitates decisions about timing of drain removal and progression of diet. For these reasons, we continue to use this technique in our practice.

In conclusion, duct-to-mucosa anastomotic leakage can be distinguished from parenchymal (non-anastomotic) leakage after duct-to-mucosa PJ. Both parenchymal and anastomotic pancreatic leaks contribute almost equally to pancreatic leaks after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Knowledge of the exact nature of the leak is important for optimal treatment and management of this complication.

Pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy is a significant source of morbidity and mortality, with anastomotic leaks being more refractory than parenchymal leaks. It is important to be able to distinguish one from the other so that appropriate treatment can be given.

Pancreatic surgeons need new ways to monitor pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy to know whether conservative treatment is sufficient or more aggressive treatment should be undertaken.

By analyzing pancreatographic findings, drainage volumes, and amylase levels, author found patterns among cases of pancreatic leakage that enable us to distinguish parenchymal leakage from anastomotic leakage. Specifically, in parenchymal pancreatic leakage, pancreatography showed no extravasation at the pancreatic anastomosis, yet drain amylase levels were elevated, whereas in anastomic pancreatic leakage, contrast extravasation is present and the levels of drain amylase increased until the leak started to resolve. In contrast to parenchymal leaks, anastomotic leaks tend not to resolve spontaneously.

This retrospective study identified distinguishing characteristics of parenchymal versus anastomotic leakage. These distinctions should be confirmed prospectively and can be used clinically to provide better treatment after pancreatic surgery.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is a procedure that is used to treat tumors located in the head of the pancreas. Parenchymal leakage refers to leakage that occurs from the resection surface of the pancreas remnant, and anastomotic leakage refers to a specific leakage that occurs due to a failure of the reconstructed duct-to-mucosa anastomosis between the pancreas remnant and the intestine.

The author evaluated the incidence of anastomotic versus parenchymal leakage following duct-to-mucosa pancreatic reconstruction in pancreaticoduodenectomy. This is a well-written paper. The findings provided great inspiration about how to consider and manage pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Peer reviewers: Wei Tang, MD, EngD, Assistant Professor, H-B-P Surgery Division, Artificial Organ and Transplantation Division, Department of Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, the University of Tokyo, Tokyo 113-8655, Japan; Bernd Sido, PhD, Department of General and Abdominal Surgery, Teaching Hospital of the University of Regensburg, Hospital Barmherzige Brüder, Prüfeninger Strasse 86, Regensburg D-93049, Germany

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Bartoli FG, Arnone GB, Ravera G, Bachi V. Pancreatic fistula and relative mortality in malignant disease after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Review and statistical meta-analysis regarding 15 years of literature. Anticancer Res. 1991;11:1831-1848. |

| 2. | Z'graggen K, Uhl W, Friess H, Buchler MW. How to do a safe pancreatic anastomosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:733-737. |

| 3. | Evans DB, Lee JE, Pisters PWT. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple Operation) and total pancreatectomy for cancer. Mastery of surgery, 4th ed. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins 2001; 1299-1318. |

| 4. | Suzuki Y, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, Hiraoka K, Takada M, Ajiki T, Takeyama Y, Ku Y, Kuroda Y. Selection of pancreaticojejunostomy techniques according to pancreatic texture and duct size. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1044-1047; discussion 1048. |

| 5. | Reissman P, Perry Y, Cuenca A, Bloom A, Eid A, Shiloni E, Rivkind A, Durst A. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus controlled pancreaticocutaneous fistula in pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1995;169:585-588. |

| 6. | Katsaragakis S, Antonakis P, Konstadoulakis MM, Androulakis G. Reconstruction of the pancreatic duct after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a modification of the Whipple procedure. J Surg Oncol. 2001;77:26-29; discussion 30. |

| 7. | Grobmyer SR, Rivadeneira DE, Goodman CA, Mackrell P, Lieberman MD, Daly JM. Pancreatic anastomotic failure after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 2000;180:117-120. |

| 8. | Lau ST, Simchuk EJ, Kozarek RA, Traverso LW. A pancreatic ductal leak should be sought to direct treatment in patients with acute pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2001;181:411-415. |

| 9. | Brodsky JT, Turnbull AD. Arterial hemorrhage after pancreatoduodenectomy. The 'sentinel bleed'. Arch Surg. 1991;126:1037-1040. |

| 10. | Smith CD, Sarr MG, vanHeerden JA. Completion pancreatectomy following pancreaticoduodenectomy: clinical experience. World J Surg. 1992;16:521-524. |

| 11. | van Berge Henegouwen MI, De Wit LT, Van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Incidence, risk factors, and treatment of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: drainage versus resection of the pancreatic remnant. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:18-24. |

| 12. | Choi SH, Moon HJ, Heo JS, Joh JW, Kim YI. Delayed hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:186-191. |

| 13. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. |

| 14. | Matsumoto Y, Fujii H, Miura K, Inoue S, Sekikawa T, Aoyama H, Ohnishi N, Sakai K, Suda K. Successful pancreatojejunal anastomosis for pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;175:555-562. |

| 15. | Ohwada S, Ogawa T, Kawate S, Tanahashi Y, Iwazaki S, Tomizawa N, Yamada T, Ohya T, Morishita Y. Results of duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy for pancreaticoduodenectomy Billroth I type reconstruction in 100 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:29-35. |

| 16. | Cullen JJ, Sarr MG, Ilstrup DM. Pancreatic anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, significance, and management. Am J Surg. 1994;168:295-298. |

| 17. | Yeh TS, Jan YY, Jeng LB, Hwang TL, Wang CS, Chen SC, Chao TC, Chen MF. Pancreaticojejunal anastomotic leak after pancreaticoduodenectomy--multivariate analysis of perioperative risk factors. J Surg Res. 1997;67:119-125. |

| 18. | Howard JM. Pancreatojejunostomy: leakage is a preventable complication of the Whipple resection. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:454-457. |

| 19. | Matsusue S, Takeda H, Nakamura Y, Nishimura S, Koizumi S. A prospective analysis of the factors influencing pancreaticojejunostomy performed using a single method, in 100 consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Surg Today. 1998;28:719-726. |

| 20. | Kazanjian KK, Hines OJ, Eibl G, Reber HA. Management of pancreatic fistulas after pancreaticoduodenectomy: results in 437 consecutive patients. Arch Surg. 2005;140:849-854; discussion 854-856. |

| 21. | Biehl T, Traverso LW. Is stenting necessary for a successful pancreatic anastomosis? Am J Surg. 1992;163:530-532. |

| 22. | Yang YM, Tian XD, Zhuang Y, Wang WM, Wan YL, Huang YT. Risk factors of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2456-2461. |