Published online Nov 14, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6581

Revised: August 13, 2008

Accepted: August 20, 2008

Published online: November 14, 2008

Retrorectal cysts are rare benign lesions in the presacral space which are frequently diagnosed in middle-aged females. We report here our experience with two symptomatic female patients who were diagnosed as having a retrorectal cyst and managed using a laparoscopic approach. The two patients were misdiagnosed as having an ovarian cystic lesion after abdominal ultrasonography. Computer tomography (CT) scan was mandatory to establish the diagnosis. The trocar port site was the same in both patients. An additional left oophorectomy was done for a coexisting ovarian cystic lesion in one patient in the same setting. There was no postoperative morbidity or mortality and the two patients were discharged on the 5th and 6th post operative days, respectively. Our cases show that laparoscopic management of retrorectal cysts is a safe approach. It reduces surgical trauma and offers an excellent tool for perfect visualization of the deep structures in the presacral space.

- Citation: Gunkova P, Martinek L, Dostalik J, Gunka I, Vavra P, Mazur M. Laparoscopic approach to retrorectal cyst. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(42): 6581-6583

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i42/6581.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6581

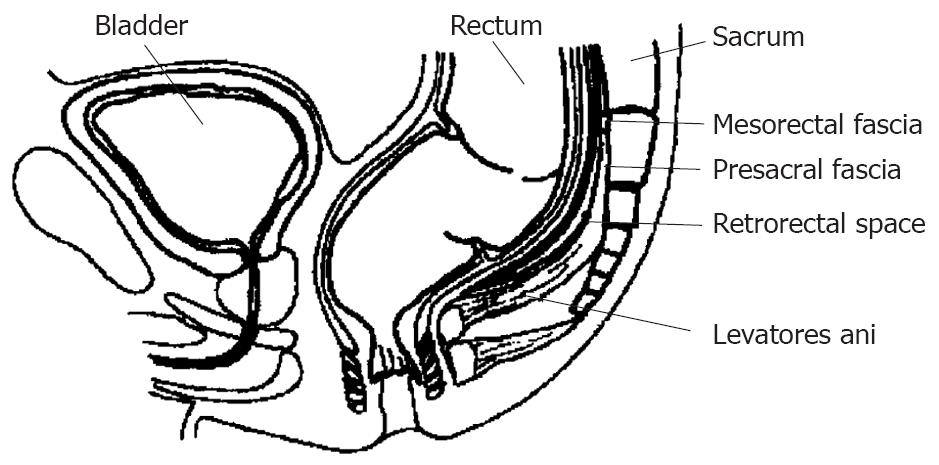

The retrorectal space (Figure 1) is defined as the space bounded by the sacrum posteriorly, the rectum anteriorly, the peritoneal reflection superiorly, the levator ani and coccygeus muscles inferiorly. Its lateral margins are formed by the ureters and iliac vessels.

Cystic lesions arising in this space are known as retrorectal or presacral cysts and their incidence rate is one in approximately 40 000 patients[1]. Although they can be found in all age groups including infants, they are frequently diagnosed in women (81%), in their middle-age[2]. They are benign in most of the cases, but malignant degeneration is rare. If they turn malignant, they are commonly diagnosed histopathologically as adenocarcinoma or carcinoid[3]. In cases of malignancy, prognosis depends upon acheiving total surgical excision with clear margins as well as their histopathological criteria. The prognosis of adenocarcinoma is unfavourable.

Retrorectal cysts can be uni or multilocular. The content in retrorectal cysts varies from clear fluid to dense mucus. Calcifications can occur in the wall of the cyst and septa can be found inside. The lining consists of more than one type of epithelium. It is often surrounded by scattered bundles of smooth muscle but has no myenteric plexus or serosa.

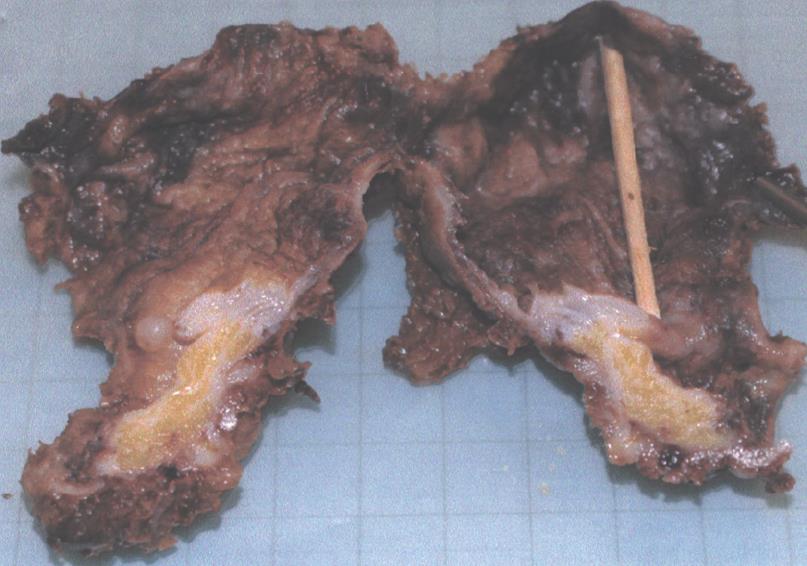

The first case was a 43-year-old woman. She underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy procedure after a suspecious cyst was found in the left ovary at sonography. The laparoscopic diagnosis was negative. The patient suffered from permanent abdominal pain and was further investigated using a computer tomography (CT) scan which showed a 9.5 cm × 4 cm × 6 cm well circumscribed cystic lesion in the presacral space, to the left of the rectum. Rectoscopy did not demonstrate any extraluminal pressure and coloscopy was also negative. The patient submitted to a laparoscopic operation for cyst excision. A 10 cm × 8 cm × 6 cm cyst with white mucous content was extracted laparoscopically (Figure 2). Histopathological examination of the cyst showed dysontogenetic origin with tuboendometrial metaplasia. Postoperative recovery of the patient was smooth with no complications. She was discharged on the 6th postoperative day.

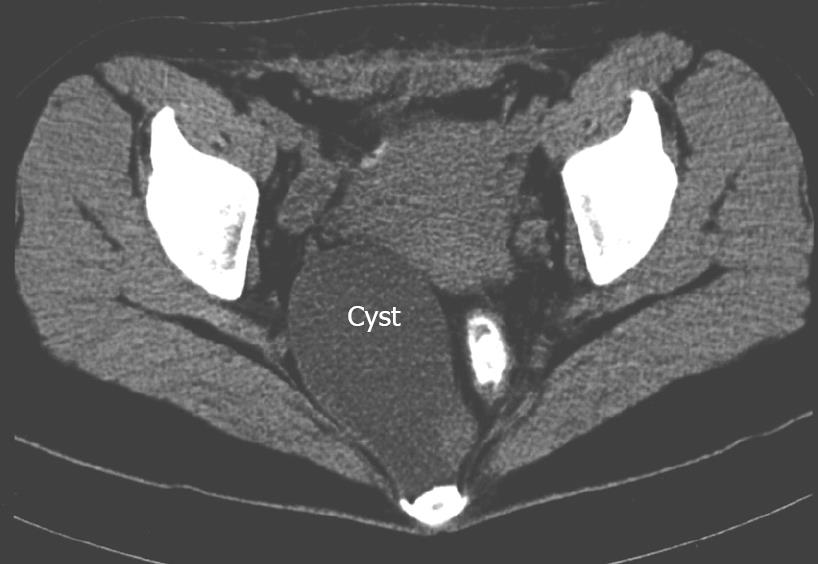

The second case was a 28-year-old woman complaining of anal pain. She underwent repeated gynecological laparoscopic operations for cysts in both ovaries. A CT scan showed cystic lesions in the left ovary and another 9.3 cm × 5.8 cm × 6.4 cm cystic mass in the presacral space (Figure 3). A 10 cm × 5.5 cm × 5 cm cyst was extracted laparoscopically. Left oophorectomy was performed in the same setting. Histopathological examination of the cyst confirmed its benign origin which is lined by simple columnar ciliated epithelium. The postoperative recovery was smooth and the patient was discharged on the 5th postoperative day.

The same laparoscopic approach was used in both cases. After peritoneal insufflation, the pressure was maintained at 11 mmHg. A 10 mm umbilical trocar, a 12 mm trocar in the right hypogastrium and a 5 mm trocar in the right mesogastrium were used for camera and the surgeon working hands, respectively. A 10 mm trocar in the left hypogastrium and a 5 mm trocar in the left mesogastrium were used for the assistance. The retrorectal space was opened using a harmonic scalpel at the sacral promontory level, the mesorectum was dissected free and the cystic lesion was identified. The cyst was resected using a harmonic scalpel after its complete dissection and separation from the surrounding structures. The pelvic floor was reconstructed with suture and a drain was placed in the Douglas pouch. The total operation time was 75 min for the first case and 90 min for the second case.

Retrorectal cystic hamartoma (hindgut cyst) is a rare developmental lesion arising from the vestiges of the embryonic hind gut[4]. Other developmental cysts (epidermoid, dermoid with skin appendages and rectal cystic duplication with well-defined muscle layers, myenteric plexus and serosa) can occur in retrorectal space[5]. Anal gland cysts can develop near the anal sphincter. All these cysts are similar to retrorectal cystic hamartoma and their exact diagnosis depends on the histopathological examination including immunohistochemical profile.

Retrorectal cysts are asymptomatic in 50% of the cases and the lesion is an incidental finding. A cyst becomes symptomatic due to its mass effects on surrounding organs (rectal fullness, painful defecation, dysuria). Cysts with secondary infection have typical symptoms of abscess and fistula. Perianal changes and a draining sinus in the sacrococcygeal area can be found. The presence of retrorectal cyst can bring about the risk of complicated labor.

Diagnosis of cysts by ultrasound is difficult, and cysts can be easily misdiagnosed as an ovarian lesion, especially if the ovaries are not visualized precisely. Since diagnostic laparoscopy can be false-negative because of retroperitoneal localization of the cyst, it is necessary to think of a retrorectal cyst when ultrasound shows a cyst and laparoscopic findings are negative.

Computed tomography (CT) and MR imaging are necessary to confirm the diagnosis of cysts[6]. CT scans usually show the cyst as a well-circumscribed hypodense retrorectal lesion without invasion of its adjacent structures. Infection of a cyst may cause wall thickening. Parietal calcifications can be found, but they are more typical in dermoid cysts, teratoma, neuroblastoma, chordoma and mucinous adenocarcinoma. The cyst signal on MR imaging depends on its content. Malignant changes are suspected in a case of focal parietal thickening or with invasion of the adjacent organs[7].

Endorectal ultrasound can also be useful[8]. Rectoscopy or sigmoidoscopy can verify external compression on the rectum. Digital rectal examination is simple, but essential for cyst diagnosis because 75% of retrorectal masses are palpable.

Routine preoperative biopsy (transrectal or transcutaneous) is not recommended because it carries a significant hazard of spillage of possible malignant cells into the peritoneal cavity and can lead to infection of cyst[2,8]. CT-guided extrarectal or presacral approach is indicated in case of inoperable or locally advanced lesion or in patients at a high surgical risk[2,8]. Histopathological examination is necessary to determine adjuvant therapy.

The differential diagnosis of a retrorectal cyst includes malignant and inflammatory lesions which can occur in presacral space. Chordoma is the most common primary tumor, followed by leiomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma, chondrosarcomas, hemangiopericytoma, teratocarcinoma, squamous-cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma[9], carcinoid[10] and adenocarcinoma. Adnexal tumor or endometriosis is difficult to diagnose[11]. Malignant lesions are solid with signs of local invasion and bone destruction. Sacrococcygeal teratoma with cystic and solid components and calcification is usually discovered in neonates. Anterior sacral meningocele is associated with sacral defect. Primary retrorectal adenocarcinoma arising from cystic lesions (hind gut cysts) is rare[12]. Lipoma, myelolipoma and hemangioma are rare in presacral space too. For completeness, it is necessary to mention bone tumors including osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, giant cell tumor, bone cysts and bone metastases. Infected hindgut cyst may be misdiagnosed as a pilonidal cyst, an anorectal fistula or a recurrent rectal abscess.

Surgery is the first line in management. Simple cyst marsupialisation with drainage is insufficient and leads to recurrence and possible infection. Surgical approaches used for excision are as follows: anterior (abdominal), posterior (intersphincteric, parasacrococcygeal, transsphincteric, transsacral, transsacrococcygeal[13], transanorectal, transvaginal) or combinated. The approach depends on location, size of the lesion and its relationship with adjacent structures[14]. Digital rectal examination is helpful for the choice of approach. If the superior border of tumor can be palpated, the posterior approach can be performed successfully. The posterior (most often transsacral or parasacral) approach is indicated for low-lying tumors (below the sacral promontory) and the abdominal approach is recommended for lesions above the sacral promontory. Laparoscopic transabdominal approach presents a minimally invasive approach with reduced surgical trauma and an excellent means for visualization of the presacral space and its contents[15,16].

In conclusion, laparoscopic excision of retrorectal systs is a safe and efficient option. Laparoscopic approach minimizes the surgical trauma and offers perfect visualization of the deep structures in the presacral space.

Peer reviewers: Conor P Delaney, MD, Department of Surgery, Institute for Surgery and Innovation, University Hospitals, Case Medical Center, 11100 Euclid Avenue OH, Cleveland 44106-5047, United States; Yutaka Saito, Division of Endoscopy, National Cancer Center Hospital, 5-1-1, Tsukiji, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-0045, Japan

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Yin DH

| 1. | Jao SW, Beart RW Jr, Spencer RJ, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM. Retrorectal tumors. Mayo Clinic experience, 1960-1979. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:644-652. |

| 2. | Singer MA, Cintron JR, Martz JE, Schoetz DJ, Abcarian H. Retrorectal cyst: a rare tumor frequently misdiagnosed. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:880-886. |

| 3. | Prasad AR, Amin MB, Randolph TL, Lee CS, Ma CK. Retrorectal cystic hamartoma: report of 5 cases with malignancy arising in 2. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:725-729. |

| 4. | Hjermstad BM, Helwig EB. Tailgut cysts. Report of 53 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;89:139-147. |

| 5. | Leborgne J, Guiberteau B, Lehur PA, Le Goff M, Le Neel JC, Nomballais MF. [Retro-rectal cystic tumors of developmental origin in adults. Apropos of 2 cases]. Chirurgie. 1989;115:565-571. |

| 6. | Liessi G, Cesari S, Pavanello M, Butini R. Tailgut cysts: CT and MR findings. Abdom Imaging. 1995;20:256-258. |

| 7. | Lim KE, Hsu WC, Wang CR. Tailgut cyst with malignancy: MR imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1488-1490. |

| 8. | Wolpert A, Beer-Gabel M, Lifschitz O, Zbar AP. The management of presacral masses in the adult. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;6:43-49. |

| 9. | Mourra N, Caplin S, Parc R, Flejou JF. Presacral neuroendocrine carcinoma developed in a tailgut cyst: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:411-413. |

| 10. | Edelstein PS, Wong WD, La Valleur J, Rothenberger DA. Carcinoid tumor: an extremely unusual presacral lesion. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:938-942. |

| 11. | Rana S, Stanhope RC, Gaffey T, Morrey BF, Dumesic DA. Retroperitoneal endometriosis causing unilateral hip pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:970-972. |

| 12. | Puccio F, Solazzo M, Marciano P, Fadani R, Regina P, Benzi F. Primary retrorectal adenocarcinoma: report of a case. Tech Coloproctol. 2003;7:55-57. |

| 13. | Canessa CE. Dorsal transsacrococcygeal rectal approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1663-1665. |

| 14. | Lev-Chelouche D, Gutman M, Goldman G, Even-Sapir E, Meller I, Issakov J, Klausner JM, Rabau M. Presacral tumors: a practical classification and treatment of a unique and heterogeneous group of diseases. Surgery. 2003;133:473-478. |

| 15. | Bax NM, van der Zee DC. The laparoscopic approach to sacrococcygeal teratomas. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:128-130. |

| 16. | Konstantinidis K, Theodoropoulos GE, Sambalis G, Georgiou M, Vorias M, Anastassakou K, Mpontozoglou N. Laparoscopic resection of presacral schwannomas. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15:302-304. |