Published online Nov 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6421

Revised: October 14, 2008

Accepted: October 21, 2008

Published online: November 7, 2008

Splenic tumors are rare. Differentiation of the tumors before operation is of great value regarding the outcome. A case of a 32-year-old man with a splenic inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) mimicking splenic angiosarcoma is described. The tumor was highly suspected of being splenic angiosarcoma based on radiological findings preoperatively. However, after splenectomy, histopathological examinations revealed splenic IPT. Splenic IPT and angiosarcoma are rare and often pose diagnostic difficulties because the clinical and radiological findings are obscure. Due to large differences in prognosis, we briefly reviewed the clinical, radiological, and pathological features of both of the tumors.

- Citation: Hsu CW, Lin CH, Yang TL, Chang HT. Splenic inflammatory pseudotumor mimicking angiosarcoma. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(41): 6421-6424

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i41/6421.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6421

Although splenic tumors are rare, differentiation of the tumors before operation is of great value. Among them, splenic inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) is a benign tumor characterized microscopically by a proliferation of inflammatory cells[1]; but splenic angiosarcoma is a dismal malignancy of vascular origin[2]. We usually differentiate them before operation by imaging studies. In this report, we present a case of splenic IPT mimicking angiosarcoma on radiological findings.

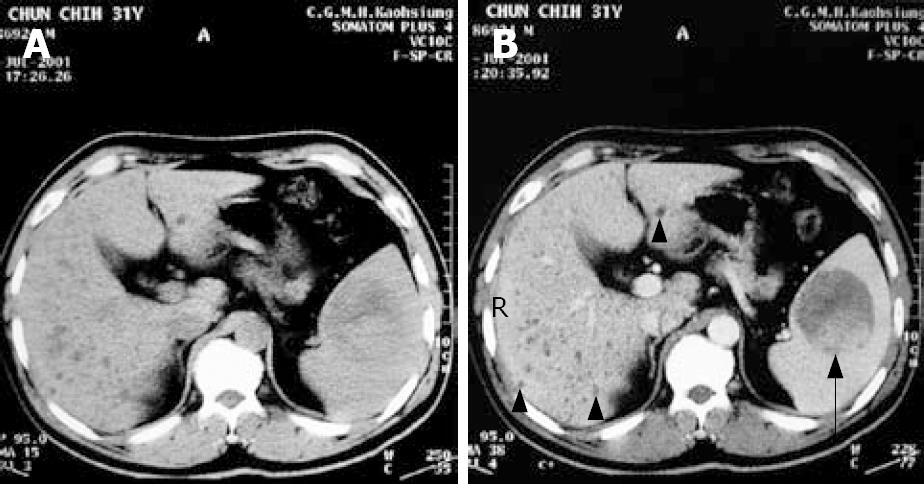

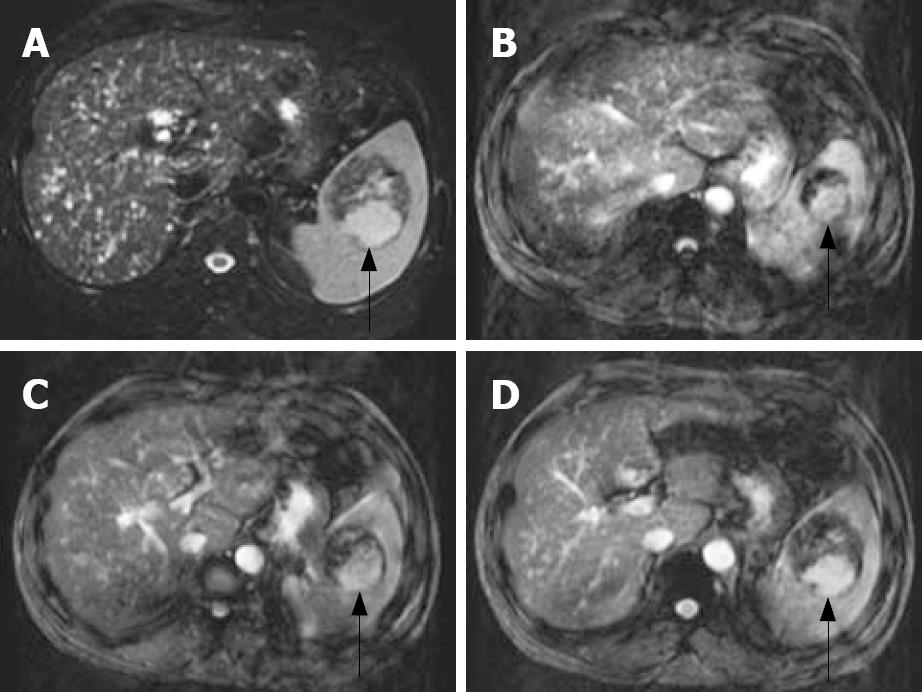

A 32-year-old man was a carrier of hepatitis B virus for years with regular follow-up at outpatient clinics. A splenic mass was incidentally detected by sonography. Physical examinations were unremarkable. The patient had no systemic complaints except mild vague discomfort over the epigastric region. Biochemical and hematological investigations were all within normal ranges except for slightly elevated serum glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase (SGOT). Tumor markers including CEA, AFP, CA-199, and CA-125 were all negative. Sonography of the spleen showed a well-defined encapsulated tumor, 6.3 × 6.1 cm in diameter, with hyperechoic density in the central portion (Figure 1). Non-contrast and contrast abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a mass over the spleen with high density in the central portion and multiple diffuse low-attenuation nodules in liver parenchyma (Figure 2A and B). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done for differentiation and revealed a mass lesion around 6 cm in the spleen, which showed partially dense intensity in T2-weighted image (Figure 3A) and peripheral nodule enhancement with gadolinium-contrast filling and pooling in T1 contrast-enhancement dynamic study (Figure 3B-D).

Overall, there were two parts of different signal intensity comprising the tumor at the spleen. The major part of the circumscribed lesion showed persistent low-signal intensity with some stippling enhancement from MRI dynamic contrast-enhanced series, while the minor portion located at the dorsal aspect showed similar signal-intensity change as the normal spleen parenchyma either at pre- or post-contrast phases, which is suggestive of hypervascular lesion, such as angiosarcoma.

Diffuse multiple tiny cystic lesions were noted in bilateral lobes of the liver. Biliary hamartoma was first considered. However, differential diagnosis should have included multiple hepatic cysts, micro-abscesses or even metastases. Therefore, primary splenic angiosarcoma with the possibility of multiple liver metastasis was the first consideration.

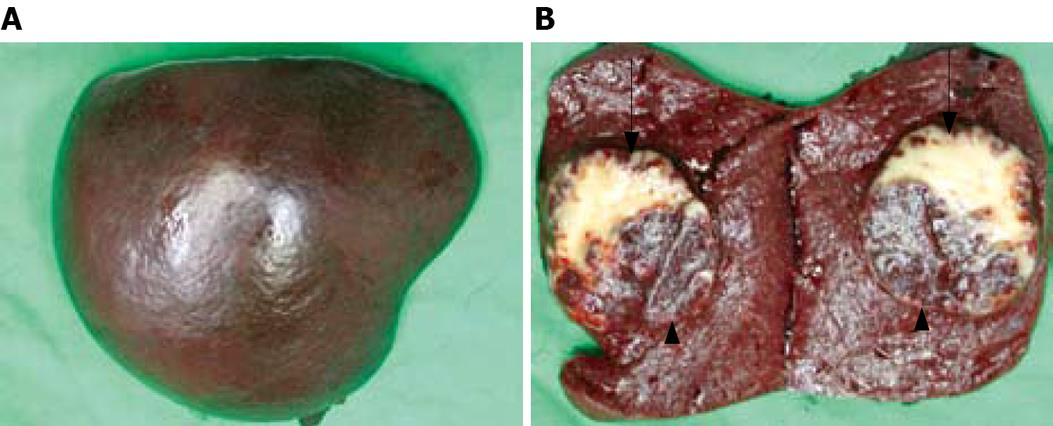

Surgical intervention was indicated, and exploratory laparotomy was performed thereafter. During the operation, the spleen was removed smoothly and liver hypertrophy with multiple tiny cystic lesions over the liver surface was noted. There was no evidence of malignancy in the frozen sections examined.

The specimen of spleen measured 11 × 8.5 × 6 cm in size and weighed 240 g (Figure 4A). Grossly, there was a well-circumscribed tumor inside the spleen, measuring 5.5 × 5.0 × 4.0 cm in size (Figure 4B). There were two parts of different appearances comprising the tumor. The major part of the circumscribed lesion showed yellowish appearance with some stippling red spots scattered over the cut surface, while the minor portion located at the dorsal aspect showed similar appearance as the normal spleen parenchyma.

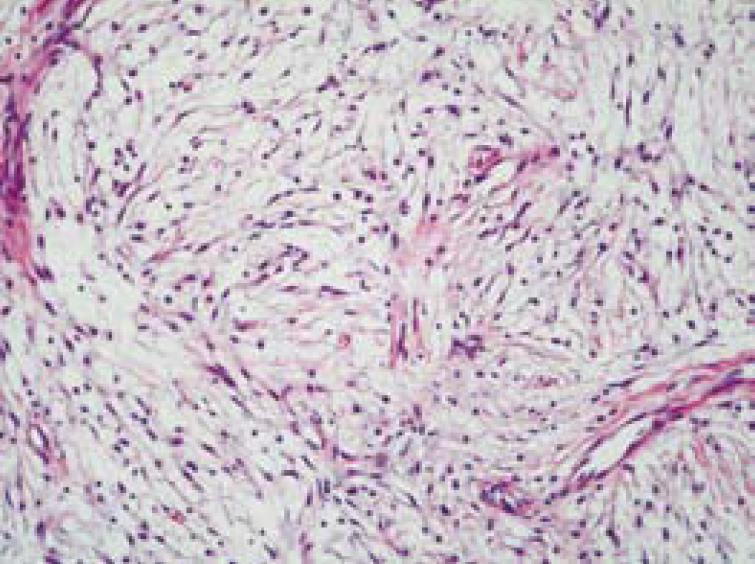

Microscopically, the sections of the specimen were composed of fibrosis, focal sclerosis, plump spindle cells and vascular proliferation (Figure 5). An admixture of inflammatory cells included lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils, in which lymphocytes were predominant. The major part of the tumor consisted of more fibrosis and focally sclerotic change, while the minor part consisted of more vascular proliferation and more inflammatory cell infiltration. The sections of the specimen were compatible with the picture of IPT.

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and he has been well for 3 years following surgery.

The term “inflammatory pseudotumor” was first proposed in 1954, since these lesions are composed of inflammatory cells. Inflammatory pseudotumors have been reported in several anatomic locations, such as orbit, respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, and liver[3]. However, splenic involvement is extremely rare. The first 2 cases of splenic inflammatory pseudotumor were reported in 1984. About one-half of the lesions are discovered incidentally during work-up for other malignancies after splenectomy for other conditions such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or at autopsy[4]. Clinical symptoms are not specific to the disease, with left upper quadrant or epigastric pain. Splenomegaly is usually present. Laboratory investigations may reveal fever, anemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, thrombocytosis, or hypersplenism; however, more than one-third of the cases reported showed no evidence of any abnormality in laboratory investigations[1]. Other patients have signs of immune thrombocytopenic purpura[4]. However, our patient only had history of hepatitis B with mild vague abdominal discomfort.

There are several radiological modalities suggested for diagnosing splenic IPT, including ultrasonography, CT, and MRI. Ultrasonography usually shows a low echoic mass in most cases[5]. CT is the radiological test that most often demonstrates the presence of a splenic lesion and usually demonstrates a low-density mass in both the non-enhanced and enhanced modes. Although CT is quite sensitive, this modality is not specific in differentiating between splenic IPT and other malignancies[3]. MRI findings usually show an iso- or low-intensity mass on the T1-weighted images and a low-intensity mass on the T2-weighted images, while also demonstrating a low-intensity in the early phase and a high-intensity mass in the delayed phase of a dynamic study. However, the same criticism can be said about MRI with T1- and T2-weighted imaging for the poor specificity in differentiating pseudotumors from other malignancies[3].

Gross features in all reported cases of splenic IPT are described as a solitary well-circumscribed lesion with a white or tan cut surface that compresses the adjacent splenic parenchyma. Histological examinations of specimens are composed of acute and chronic inflammatory cells infiltrating a stroma of mesenchymal myofibroblastic spindle cells. The inflammatory cells are predominantly plasma cells, mature lymphocytes, and rarely eosinophils.

Etiology and pathogenesis of IPT remain unknown. Some characteristics described support an immunologic disorder[4]. Pathologic features of pseudotumor may be related to the production of mediators in inflammation, and note that interleukin-1 can produce local lesions and systemic manifestations with IPT. In addition, granulomatous inflammation process, focal parenchymal necrosis with hemorrhage, disturbance of blood supply or bacterial or viral infection have all been speculated in the pathogenesis of splenic IPT[6].

If a primary splenic tumor is suspected, splenectomy is required for diagnostic purposes and for therapy. Laparoscopic surgery for benign splenic tumors is considered to be a valid procedure. However, if the splenic lesions have a malignant potential, laparoscopic surgery elevates the risk of either intra-abdominal dissemination or skin metastasis. Therefore, if malignant splenic tumor can not be ruled out, laparoscopic surgery is not suggested[7].

Angiosarcoma is a malignancy of vascular origin, and is characterized by masses of endothelial cells with cellular atypia and anaplasia[2]. Angiosarcoma may occur anywhere in the body, but most often in the skin, soft tissues, breast and liver. Splenic involvement is exceedingly rare. Clinical manifestations include abdominal discomforts, splenomegaly and signs of immune thrombocytopenic purpura[2], which were not specific to the disease. Pathogenesis remains obscure. Prognosis is extremely poor, with a 6-month survival rate of 20%[8]. The tumor commonly metastasizes to the liver, lung, bone, lymph nodes, omentum, or peritoneum.

There are also several radiological modalities suggested for diagnosing splenic angiosarcoma including sonography, CT, MRI and angiography. Unlike splenic pseudotumor, sonographic findings in splenic angiosarcoma show a heterogeneous mass or multiple reflective areas[8,9]. CT may demonstrate hypoattenuating lesions on nonenhanced scans. Areas of high attenuation on noncontrast CT may represent acute hemorrhage or hemosiderin deposits. Contrast enhancement of angiosarcoma may show some enhancements similar to that of hepatic hemangioma[2]. The MRI appearance of splenic hemangioma is similar to that of hemangioma of the liver. The lesion will be hypo- or isointense on T1-weighted MR images and hypertense on T2-weighted MR images. T1-weighted images obtained after contrast administration may demonstrate a difference between the cystic and solid components[2]. The most specific modality to differentiate splenic IPT from angiosarcoma is angiography. Angiographic findings of angiosarcoma show a hypervascular tumor with contrast pooling, and that of splenic IPT usually show avascular or hypovascular tumor[10].

In the present case, sonography showed hyperechoic density in the central portion of the tumor. CT also showed a high density area and partial enhancement in the central portion of splenic tumor with multiple diffuse low-attenuation nodules in liver. MRI revealed a mass, which showed partial dense intensity in T2-weighted image. In T1 mode with gadolinium-enhancement, peripheral nodule with contrast filling and pooling, which was compatible with a picture of angiosarcoma, was noted. Therefore, the first impression of angiosarcoma with suspected liver metastasis was reasonable preoperatively. The reason why splenic IPT could mimic the picture of angiosarcoma could be explained by the hypervascular component within the minor part of the tumor, which absorbed the contrast medium in radiological examination. Accordingly, the ITP should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of splenic space-occupying lesions even if the imaging modality does not favor it.

Peer reviewer: Xiao-Ping Chen, Professor, Institute of Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery, Tongji Hospital, 1095# Jie-fang Da-dao,Wuhan 430030, Hubei Province, China

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Li M E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Ozkara SK, Gurbuz Y, Ercin C, Muezzinoglu B, Turkmen M. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:629-631. |

| 2. | Thompson WM, Levy AD, Aguilera NS, Gorospe L, Abbott RM. Angiosarcoma of the spleen: imaging characteristics in 12 patients. Radiology. 2005;235:106-115. |

| 3. | Chen WH, Liu TP, Liu CL, Tzen CY. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen. J Chin Med Assoc. 2004;67:533-536. |

| 4. | Hatsuse M, Murakami S, Haruyama H, Inaba T, Shimazaki C. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen complicated by idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:619-620. |

| 5. | Hayasaka K, Soeda S, Hirayama M, Tanaka Y. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen: US and MRI findings. Radiat Med. 1998;16:47-50. |

| 6. | Neuhauser TS, Derringer GA, Thompson LD, Fanburg-Smith JC, Aguilera NS, Andriko J, Chu WS, Abbondanzo SL. Splenic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor): a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 12 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:379-385. |

| 7. | Tsugawa K, Hashizume M, Migou S, Kawanaka H, Sugimachi K, Irie H, Maeda T, Akaboshi K. Laparoscopic splenectomy for an inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen: operative technique and case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1887-1891. |

| 8. | Hai SA, Genato R, Gressel I, Khan P. Primary splenic angiosarcoma: case report and literature review. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:143-146. |

| 9. | Ha HK, Kim HH, Kim BK, Han JK, Choi BI. Primary angiosarcoma of the spleen. CT and MR imaging. Acta Radiol. 1994;35:455-458. |

| 10. | Moriyama S, Inayoshi A, Kurano R. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the spleen: report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30:942-946. |