Published online Oct 28, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6213

Revised: October 13, 2008

Accepted: October 20, 2008

Published online: October 28, 2008

AIM: To evaluate survival rate and clinical outcome of cholangiocarcinoma.

METHODS: The medical records of 34 patients with cholangiocarcinoma, seen at a single hospital between the years 1999-2006, were retrospectively reviewed.

RESULTS: Thirty-four patients with a median age of 75 years were included. Seventeen (50%) had painless jaundice at presentation. Sixteen (47.1%) were perihilar, 15 (44.1%) extrahepatic and three (8.8%) intrahepatic. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) and/or magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRCP) were used for the diagnosis. Pathologic confirmation was obtained in seven and positive cytological examination in three. Thirteen patients had co-morbidities (38.2%). Four cases were managed with complete surgical resection. All the rest of the cases (30) were characterized as non-resectable due to advanced stage of the disease. Palliative biliary drainage was performed in 26/30 (86.6%). The mean follow-up was 32 mo (95% CI, 20-43 mo). Overall median survival was 8.7 mo (95% CI, 2-16 mo). The probability of 1-year, 2-year and 3-year survival was 46%, 20% and 7%, respectively. The survival was slightly longer in patients who underwent resection compared to those who did not, but this difference failed to reach statistical significance. Patients who underwent biliary drainage had an advantage in survival compared to those who did not (probability of survival 53% vs 0% at 1 year, respectively, P = 0.038).

CONCLUSION: Patients with cholangiocarcinoma were usually elderly with co-morbidities and/or advanced disease at presentation. Even though a slight amelioration in survival with palliative biliary drainage was observed, patients had dismal outcome without resection of the tumor.

- Citation: Alexopoulou A, Soultati A, Dourakis SP, Vasilieva L, Archimandritis AJ. Cholangiocarcinoma: A 7-year experience at a single center in Greece. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(40): 6213-6217

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i40/6213.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6213

| Patient characteristics | |

| Gender (M %) | 18/34 (53%) |

| Age (years) | 71.7 ± 13.3 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 13.3 ± 9.1 |

| AST (U/mL) | 117 ± 80 |

| ALP (U/mL) | 472 ± 237 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.6 ± 0.5 |

| Predisposing factor (%) | 4/34 (11.7%) |

| Tobacco use (%) | 10/34 (29.4%) |

Cholangiocarcinoma is the second commonest primary hepatic malignant disease, after hepatocellular carcinoma[1]. Several studies have shown that the incidence and mortality of the disease are rising worldwide[1,2]. The high fatality rate has been attributed to the poor knowledge of the tumor pathogenesis and the paucity of effective methods of diagnosis and management. First, the diagnosis of perihilar and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma still remains a clinical challenge, particularly in the presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Second, surgical resection is the only curative option for cholangiocarcinoma, but only a minority of patients are suitable for resection[3,4]. Factors that have been considered as contraindications for resectability include, among others, metastatic disease, multiple comorbidities, invasion of the hepatic artery or portal vein and extension of cholangiocarcinoma to involve segmental bile ducts on both liver lobes[3,4,5]. Sometimes the lack of available surgical expertise renders the surgical approach difficult to apply.

We aimed at evaluating the clinical features, diagnostic modalities, therapeutic options and survival rates in a series of 34 patients with cholangiocarcinoma hospitalized at the Hippokration University Hospital, Athens, Greece. We also attempted to investigate whether there were differences in survival, compared to data published in the literature, and to identify factors associated with survival.

The medical records of 34 patients diagnosed with cholangiocarcinoma at the Hippokration University Hospital between January 1999 and December 2006 were retrospectively reviewed. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee. Our hospital has a liver unit and several patients with cholangiocarcinoma are referred from other hospitals. Diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma was based upon clinical, imaging, cytologic and histopathologic findings. Medical records were scrutinized for epidemiologic characteristics, predisposing factors, initial manifestations of the disease, method of diagnosis, laboratory findings, surgical or palliative therapy, and overall morbidity and mortality.

Cholangiocarcinoma was classified as intrahepatic, perihilar and distal extrahepatic type[3,6]. The staging of the tumor was based on the tumor-node-metastasis system[7]. The perihilar tumors were classified according to the Bismuth classification[8] and the resectability was evaluated according to T-stage criteria[4]. All patients had ultrasound of the liver and gallbladder as the first diagnostic imaging procedure. Metastatic disease was evaluated by imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis by helical computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). No laparoscopic staging was performed.

Statistical data were analyzed using SPSS 13.0 for Windows. Descriptive statistics including mean, ranges and standard deviation values were calculated for all the continuous baseline demographic and laboratory characteristics. We used the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test to compare continuous data. The results are presented as means ± 95% confidence intervals (CI). The χ2 test was used to compare categorical data; the results are presented as counts with percentages. All reported P values are based on two-tailed tests of significance. Comparisons were considered significantly different if P < 0.05. Overall survival was estimated from the admission of the patient to the hospital until death or last follow-up visit. Survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Univariate analysis using the Cox regression test was used to determine factors associated with survival.

The study group included 18 men and 16 women, all of Greek origin. Sixteen of 34 (47.1%) were perihilar, 15 (44.1%) extrahepatic and three (8.8%) intrahepatic tumors. Demographic characteristics and laboratory data on presentation are shown in Table 1. Initial manifestations were painless jaundice in 17 patients (50%), whereas 12 (35.3%) presented with abdominal pain and weight loss.

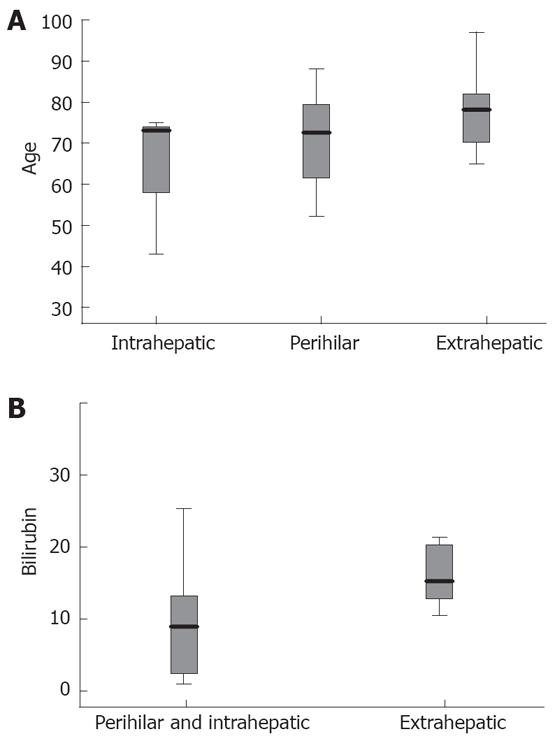

Patients with extrahepatic type of cholangio-carcinoma were older than those with perihilar and intrahepatic type, but the difference was not statistically significant (79 ± 8.4 years vs 72.5 ± 11 years and 63.6 ± 17.9 years respectively, P = 0.181, Figure 1A). Mean values of total bilirubin were higher in the extrahepatic than in perihilar and intrahepatic type (17 ± 9 mg/dL vs 8.9 ± 7.5 mg/dL, P = 0.027, Figure 1B).

A history of a predisposing factor was recognized in four patients, two with primary sclerosing cholangitis and two with chronic hepatitis B and cirrhosis. No case of Caroli’s syndrome, congenital hepatic fibrosis, choledochal cyst or occupation in the chemical industry was found. Moderate consumption of alcohol and use of tobacco were present in four (11.7%) and 10 (29.4%) patients, respectively. Thirteen (38.2%) patients presented with co-morbidities, mostly diabetes mellitus with complications and/or coronary disease.

Intrahepatic tumors were histologically proven using a CT-guided biopsy. Eight of 16 (50%) perihilar tumors were diagnosed by magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRCP) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), 4/16 (25%) by endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP) and 4/16 (25%) by histology (biopsies were obtained at laparoscopy in three cases and at endoscopic ultrasound in one case). Five of 15 (33%) extrahepatic tumors were diagnosed by MRCP/MRI, and 10/15 (66%) by ERCP. Overall, tissue for pathologic confirmation was obtained from seven patients, three with intrahepatic and four with perihilar tumors. A positive cytologic examination was obtained in three further cases.

A local surgical team evaluated the cases as resectable or non-resectable. Four cases were managed with complete surgical resection aiming at histologically negative resection margins (two extrahepatic, one perihilar and one intrahepatic type). All of the remaining cases were characterized as non-resectable. Among the 15 unresectable perihilar tumors, three (20%) were classified as T2-T3 stage, and extension of the hepatectomy was considered too risky compared to the poor patients’ performance status; nine others (60%) had evidence of either metastases or extensive local lymphadenopathy or portal vein involvement; and the three remaining patients (20%) had multiple co-morbidities. Two of three intrahepatic tumors were multifocal and were assessed as non-resectable. Three of 13 (23%) cases with unresectable extrahepatic tumors had evidence of either metastases or extensive local lymphadenopathy or portal vein involvement, and 10 (77%) had multiple co-morbidities, including cardiopulmonary disease or diabetes with complications, poor performance status and advanced age (> 80 years) and thus were considered as unsuitable for curative resection.

Palliative biliary drainage to relieve symptoms was performed in the vast majority of cases who did not undergo surgical curative therapy (12/15 perihilar, 13/13 extrahepatic, 1/2 intrahepatic). More specifically, among the perihilar-type cholangiocarcinoma cases who were not resected, eight were managed by stent placement (seven biliary stents were inserted by endoscopic and one by percutaneous routes), three by palliative percutaneous biliary drainage, and one by palliative surgical biliary drainage. No biliary decompression was decided in three cases. Among the two intrahepatic cases not resected, one was managed with palliative percutaneous biliary drainage and no biliary drainage was decided in one case. Among the 13 extrahepatic cases not resected, 12 were managed by stent placement endoscopically and one by palliative percutaneous biliary drainage.

A high number of patients who underwent a palliative biliary drainage (11/26, 42%) were managed with two or more endoscopic or percutaneous sessions for biliary decompression because of stent occlusion (median number of procedures for each patient was two, range 1-7). Metal stents were placed in the vast majority of patients.

Four cases (one intrahepatic, one extrahepatic and two perihilar type) were managed with chemotherapy without surgical resection (two in combination with biliary drainage and two without any other intervention). The causes of death in two-thirds of the patients were infective complications (acute cholangitis) following an occluded biliary stent or acute pancreatitis. Other causes of death were hepatic failure and acute myocardial infarction.

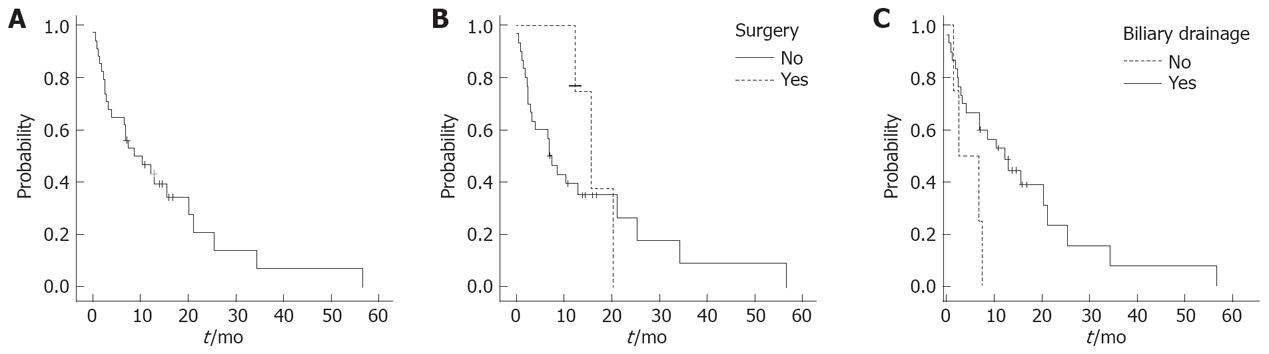

The mean follow-up for all patients was 32 mo, 95% CI 20-43 mo. Overall median survival was 8.7 mo (events, 26/34; 95% CI, 2-16 mo). The probability of 1-year, 2-year and 3-year survival was 46%, 20% and 7%, respectively (Figure 2A). The survival was longer in patients who underwent surgical resection (n = 4) compared to those who did not (n = 30), but the difference failed to reach statistical significance. The probability of survival for the former was significantly higher than for the latter (75% vs 39% and 37% vs 26% at 1 and 2 years respectively, P = 0.6, Figure 2B). The median survival was 15.7 mo, (95% CI 11-20.6 mo) in the former and 7 mo, (95% CI, 4.4-9.6 mo) in the latter group.

Patients who received any interventional treatment for biliary drainage (either stent replacement or percutaneous biliary drainage or palliative surgical procedure, n = 26) had an advantage in survival in comparison to those who did not (n = 4). The probability of survival for the former was significantly higher than for the latter (53% vs 0% at 1 year respectively; median survival, 12.3 mo; 95% CI, 6-18.7 mo and 2.5 mo, 95% CI, 0-7.6 mo, respectively; P = 0.038; Figure 2C). None of the four patients who did not undergo biliary drainage survived beyond 6 mo. None of the following factors were associated with a statistically significant difference in survival: age, gender, bilirubin, site of the tumour, albumin, stent placement, and chemotherapy.

Cholangiocarcinoma is a relatively rare disease accounting for less than 2% of all human malignancies[9]. The specific features of cholangiocarcinoma depend on the anatomical location of the tumor, which are useful to optimize the appropriate therapy. The most common location of these tumors (60%-70%) is the bifurcation of the hepatic ducts (perihilar or Klatskin tumours), while 20%-30% are extrahepatic, arising from the distal common bile duct, and 5%-10% are peripheral or intrahepatic tumors, originating from the small bile ducts of the liver parenchyma[10]. In our series, the perihilar and extrahepatic tumors had the same incidence (47% and 44%, respectively) while intrahepatic tumors accounted for a small minority (8.8%).

The distribution of age among our patients was different in the three types of tumor, with the extrahepatic cases being older, in agreement with the literature[7]. Co-morbidities were common in the extrahepatic type, as older individuals have more illnesses than younger ones. The clinical presentation and risk factors were rather similar with respect to the site of the malignancy. Painless jaundice, abdominal pain, weight loss, use of tobacco and consumption of alcohol did not show predilection for any site of the tumor. It appeared however that jaundice at presentation was more profound in the extrahepatic type of disease than in the perihilar cases. Only a few cases of cholangiocarcinoma were associated with a predisposing factor such as primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic hepatitis B, a rather low rate compared with other series[11]. Other chronic inflammatory diseases of biliary epithelium such as parasitic infections or intrahepatic biliary stones are not endemic in the Greek population.

At present, only surgical excision of all detectable tumors is associated with improvement in survival. The median survival time for patients with distal bile duct cancers who undergo resection has been reported to be about 38 mo[12,13]. The median survival time for patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma varies from 12 to 46 mo[4,14,15,16]. However, factors associated with both the patient and the tumor may preclude surgical resection. It is generally accepted that many patients are not considered surgical candidates because of co-morbidities and advanced age, despite evidence of resectable disease. On the other hand, more than half of cholangiocarcinoma cases usually present with advanced unresectable malignancy[4,17]. In our series, 50% of the patients were considered to have advanced disease and the remaining had multiple co-morbidities and/or advanced age. In the literature, neither a T2 or T3 stage nor portal involvement are considered absolute contraindications for resection for perihilar tumours[4,5]. Similarly, local lymphadenopathy is not a contraindication to resection of extrahepatic tumors[17]. Co-morbidities and advanced age along with the available local surgical expertise determined the low rate of resectability in our series. In an old series from Mayo Clinic, only 22 of 125 patients (18%) underwent curative resection, whereas 82% were candidates for palliative intervention[18]. In another more recent series of 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma, 80 (35%) underwent resection[4] while resectability rates were higher for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma ranging from 45% to 90%[19,20].

No significant survival advantage was found in patients who underwent surgical resection in our series. Curative surgical resection was attempted in only four patients and the disease recurred after resection in three of the four. It is noteworthy that no free-of-cancer surgical margins were found at histology among those three surgical specimens. The natural history of resected cholangiocarcinoma with no disease-free surgical margins is comparable to unresected cholangiocarcinoma receiving palliative therapy[4,21,22]. The overall median survival in our series was 8.7 mo, with a survival rate comparable to that reported for unresected cholangiocarcinoma from previous investigators[18,23,24].

Palliative treatment to relieve symptoms and resolve obstructive jaundice has an important role in the management of cholangiocarcinoma, since the majority of cases are not suitable for resection, as stated above, or they recur after resection[4,25]. Palliation and relief of jaundice can be accomplished by either endoscopic, percutaneous, or operative means. We found that the single factor that may provide a survival benefit in unresected cases is successful biliary decompression. It is noteworthy that of our four patients with cholangiocarcinoma with no interventional procedure for biliary decompression, none survived beyond 6 mo. Similarly, median survival for non-resectable cholangiocarcinoma has been considered as favourable in cases in which biliary drainage is performed, since the median survival has been reported to be 3 mo without and 6 mo with biliary drainage[18,26]. Our attempt to identify other factors associated with survival, e.g. gender or additional palliative therapy (i.e. chemotherapy), failed to show any survival advantage for any of them, even if some were shown to be important in previous studies[18].

Despite the benefit in survival afforded by biliary drainage, the enhancement in quality of life with this kind of intervention seemed to be minimal, since the majority of patients had repeat procedures to ensure the patency of the stents. Patency rates of self-expanding metal stents are higher than those of plastic ones[27]. Even if metal stents remain patent longer, a high percentage of our patients needed the replacement of two or more stents in repeat procedures for resolution of jaundice.

The major limitation of our study was that it involved only a single center and the number of patients was small, and thus the results may not be generalizable.

In conclusion, the present study confirms that cholangiocarcinoma is a tumor with high incidence among the elderly with multiple co-morbidities, which precludes aggressive curative resection. Moreover, survival of patients with unresected cholangiocarcinoma is short and the benefit in survival, but not in quality of life, from endoscopic or percutaneous biliary drainage, although evident, is rather weak. Therefore, early diagnosis and surgical resection of the tumor are crucial in the management of these patients.

Cholangiocarcinoma is difficult to diagnose and its prognosis is dismal due to late stage at presentation. The incidence and mortality of the disease are rising worldwide.

The high fatality rate of cholangiocarcinoma is attributed to the poor knowledge of disease pathogenesis and the paucity of effective methods of diagnosis and management. Surgical resection is the only curative option for cholangiocarcinoma, but only a minority of patients are suitable for resection.

This study confirms that cholangiocarcinoma is diagnosed at an advanced stage, with high incidence among the elderly with multiple co-morbidities, which precludes aggressive curative resection. Survival of patients with unresected cholangiocarcinoma is short and the benefit in survival, but not in quality of life, from endoscopic or percutaneous biliary drainage, although evident, is rather weak.

The study suggested that early diagnosis and surgical resection of the tumor are crucial in the management of these patients.

This is a retrospective study of the outcome of cholangiocarcinoma in a group of 34 patients seen at a single hospital, characterized by a homogeneous ethnic population of Greek origin. The aims are not ambitious and the originality of study is not high. However, the study is still relevant due to the severity of the disease and the scarce information available.

Peer reviewer: Jose JG Marin, Professor, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Salamanca, CIBERehd, Campus Miguel de Unamuno, ED-S09, Salamanca 37007, Spain

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Negro F E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Khan SA, Taylor-Robinson SD, Toledano MB, Beck A, Elliott P, Thomas HC. Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours. J Hepatol. 2002;37:806-813. |

| 2. | Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353-1357. |

| 3. | de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM. Biliary tract cancers. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1368-1378. |

| 4. | Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Gonen M, Burke EC, Bodniewicz BS J, Youssef BA M, Klimstra D, Blumgart LH. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507-517. |

| 5. | Ebata T, Nagino M, Kamiya J, Uesaka K, Nagasaka T, Nimura Y. Hepatectomy with portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: audit of 52 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2003;238:720-727. |

| 6. | Singh P, Patel T. Advances in the diagnosis, evaluation and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:294-299. |

| 7. | Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, Taylor-Robinson SD. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2005;366:1303-1314. |

| 8. | Bismuth H, Nakache R, Diamond T. Management strategies in resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1992;215:31-38. |

| 9. | Parker SL, Tong T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics, 1996. CA Cancer J Clin. 1996;46:5-27. |

| 10. | Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463-473; discussion 473-475. |

| 11. | Donato F, Gelatti U, Tagger A, Favret M, Ribero ML, Callea F, Martelli C, Savio A, Trevisi P, Nardi G. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatitis C and B virus infection, alcohol intake, and hepatolithiasis: a case-control study in Italy. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:959-964. |

| 12. | Nakeeb A, Tran KQ, Black MJ, Erickson BA, Ritch PS, Quebbeman EJ, Wilson SD, Demeure MJ, Rilling WS, Dua KS. Improved survival in resected biliary malignancies. Surgery. 2002;132:555-563; discission 563-564. |

| 13. | Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, Schleck CD, Ilstrup DM. Outcomes after curative resections of cholangiocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 1993;128:871-877; discussion 877-879. |

| 14. | Iwatsuki S, Todo S, Marsh JW, Madariaga JR, Lee RG, Dvorchik I, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (Klatskin tumors) with hepatic resection or transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:358-364. |

| 15. | Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, Werner M, Weimann A, Pichlmayr R. What constitutes long-term survival after surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma? Cancer. 1997;79:26-34. |

| 16. | Madariaga JR, Iwatsuki S, Todo S, Lee RG, Irish W, Starzl TE. Liver resection for hilar and peripheral cholangiocarcinomas: a study of 62 cases. Ann Surg. 1998;227:70-79. |

| 17. | Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1655-1667. |

| 18. | Farley DR, Weaver AL, Nagorney DM. "Natural history" of unresected cholangiocarcinoma: patient outcome after noncurative intervention. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:425-429. |

| 19. | Weber SM, Jarnagin WR, Klimstra D, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: resectability, recurrence pattern, and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:384-391. |

| 20. | Lieser MJ, Barry MK, Rowland C, Ilstrup DM, Nagorney DM. Surgical management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a 31-year experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5:41-47. |

| 21. | Rea DJ, Munoz-Juarez M, Farnell MB, Donohue JH, Que FG, Crownhart B, Larson D, Nagorney DM. Major hepatic resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of 46 patients. Arch Surg. 2004;139:514-523; discussion 523-525. |

| 22. | Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, Pisters PW, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg. 1998;228:385-394. |

| 23. | Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Lin E, Fortner JG, Brennan MF. Outcome of treatment for distal bile duct cancer. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1712-1715. |

| 24. | Nordback IH, Pitt HA, Coleman J, Venbrux AC, Dooley WC, Yeu NN, Cameron JL. Unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma: percutaneous versus operative palliation. Surgery. 1994;115:597-603. |

| 25. | Pichlmayr R, Weimann A, Klempnauer J, Oldhafer KJ, Maschek H, Tusch G, Ringe B. Surgical treatment in proximal bile duct cancer. A single-center experience. Ann Surg. 1996;224:628-638. |

| 26. | Chang WH, Kortan P, Haber GB. Outcome in patients with bifurcation tumors who undergo unilateral versus bilateral hepatic duct drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:354-362. |

| 27. | Kaassis M, Boyer J, Dumas R, Ponchon T, Coumaros D, Delcenserie R, Canard JM, Fritsch J, Rey JF, Burtin P. Plastic or metal stents for malignant stricture of the common bile duct? Results of a randomized prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:178-182. |