Published online Oct 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6030

Revised: September 27, 2008

Accepted: October 4, 2008

Published online: October 21, 2008

AIM: To evaluate the association between ineffective esophageal motility (IEM) and gastropharyngeal reflux disease (GPRD) in patients who underwent ambulatory 24-h dual-probe pH monitoring for the evaluation of supraesophageal symptoms.

METHODS: A total of 632 patients who underwent endoscopy, esophageal manometry and ambulatory 24-h dual-pH monitoring due to supraesophageal symptoms (e.g. globus, hoarseness, or cough) were enrolled. Of them, we selected the patients who had normal esophageal motility and IEM. The endoscopy and ambulatory pH monitoring findings were compared between the two groups.

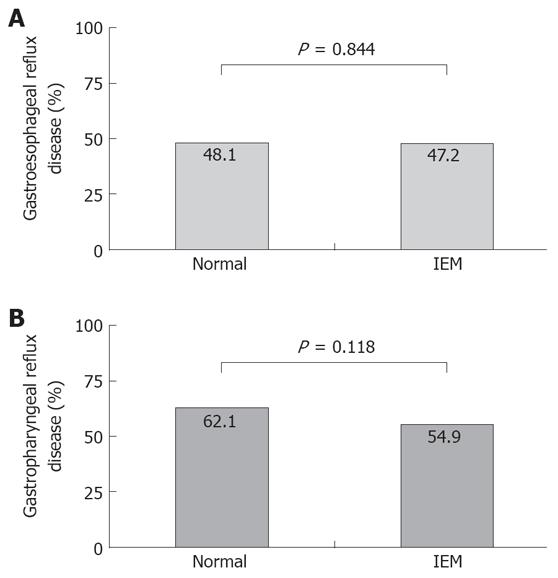

RESULTS: A total of 264 patients with normal esophageal motility and 195 patients with the diagnosis of IEM were included in this study. There was no difference in the frequency of reflux esophagitis and hiatal hernia between the two groups. All the variables showing gastroesophageal reflux and gastropharyngeal reflux were not different between the two groups. The frequency of GERD and GPRD, as defined by ambulatory pH monitoring, was not different between the two groups.

CONCLUSION: There was no association between IEM and GPRD as well as between IEM and GERD. IEM alone cannot be considered as a definitive marker for reflux disease.

- Citation: Kim KY, Kim GH, Kim DU, Wang SG, Lee BJ, Lee JC, Park DY, Song GA. Is ineffective esophageal motility associated with gastropharyngeal reflux disease? World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(39): 6030-6035

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i39/6030.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.6030

| Normal (n = 264) | IEM (n = 195) | P value | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 50.8 ± 11.1 | 51.1 ± 12.0 | 0.782 |

| Gender (men/women) | 99/165 | 87/108 | 0.125 |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 23.6 ± 2.7 | 23.2 ± 2.7 | 0.393 |

| Alcohol intake | 58 (22.0) | 31 (15.9) | 0.104 |

| Smoking | 43 (16.3) | 19 (9.7) | 0.043 |

| Heartburn/acid regurgitation1 | 128 (48.5) | 104 (53.3) | 0.304 |

| Indication for pH monitoring | 0.542 | ||

| Globus | 118 (44.7) | 88 (45.1) | |

| Hoarseness | 63 (23.9) | 35 (17.9) | |

| Cough | 27 (10.2) | 24 (12.3) | |

| Sore throat | 30 (11.4) | 28 (14.4) | |

| Others2 | 26 (9.8) | 20 (10.3) | |

| Reflux esophagitis3 | 30 (11.4) | 30 (15.4) | 0.206 |

| A | 22 | 16 | |

| B | 7 | 11 | |

| C | 1 | 2 | |

| D | 0 | 1 | |

| Hiatal hernia | 17 (6.4) | 10 (5.1) | 0.555 |

| Endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia | 23 (8.7) | 11 (5.6) | 0.214 |

| Normal (n = 264) | IEM (n = 195) | P value | |

| Lower esophageal sphincter | |||

| Pressure | 21.4 ± 0.5 | 18.6 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

| Length | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 0.921 |

| Proximal probe | |||

| Time pH < 4 (total) (%) | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.225 |

| Time pH < 4 (upright) (%) | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.230 |

| Time pH < 4 (supine) (%) | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.214 |

| No. of reflux episodes | 8.7 ± 1.0 | 12.2 ± 2.6 | 0.219 |

| Distal probe | |||

| Time pH < 4 (total) (%) | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 0.185 |

| Time pH < 4 (upright) (%) | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 0.827 |

| Time pH < 4 (supine) (%) | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 0.564 |

| No. of reflux episodes | 44.1 ± 2.5 | 47.8 ± 4.0 | 0.430 |

| No. of reflux episodes ≥ 5 min | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 0.116 |

| Longest reflux episode (min) | 8.6 ± 0.8 | 10.2 ± 1.0 | 0.199 |

| DeMeester composite score | 12.1 ± 0.9 | 14.1 ± 1.3 | 0.217 |

| Normal (n = 264) | IEM (n = 195) | |

| GERD and GPRD | 108 (40.9) | 74 (37.9) |

| GPRD only | 56 (21.2) | 33 (16.9) |

| GERD only | 19 (7.2) | 18 (9.2) |

| Normal | 81 (30.7) | 70 (35.9) |

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is characterized by increased exposure of the esophageal mucosa to the gastric contents. This is mainly due to a various combinations of an increased number of gastroesophageal reflux episodes and abnormally prolonged clearance of the refluxed material[1,2]. The mechanisms for efficient clearance are effective peristalsis, the volume of saliva and gravity.

Ineffective esophageal motility (IEM) is the most recently described esophageal motility abnormality. IEM is defined as contractions with an amplitude of less than 30 mmHg and/or with a rate of nontransmission to the distal esophagus in number of 30% or more of water swallows[3,4]. IEM is associated with an increased acid clearance times in the distal esophagus[3]. Increased acid exposure in these patients is associated with the development of erosive esophagitis and GERD-associated respiratory symptoms[5,6].

Gastropharyngeal reflux, also called laryngopha-ryngeal reflux, is a term used to describe esophageal acid reflux into the laryngeal and pharyngeal areas. It causes supraesophageal manifestations (e.g. globus, chronic cough, hoarseness, asthma, chronic sinusitis, or other pulmonary or otorhinolaryngologic diseases). Currently, the best way to demonstrate gastropharyngeal reflux is ambulatory 24-h dual probe pH monitoring[7].

It might be hypothesized that patients with IEM would be unable to clear refluxed acid; this would lead to a prolonged esophageal dwell time of the refluxed acid and then the refluxed acid would reach to a higher level. As a result, it would be presumed that patients with IEM have more gastropharyngeal reflux than those patients with normal esophageal motility.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the association between IEM and gastropharyngeal reflux in a large series of patients who underwent ambulatory 24-h dual-probe pH monitoring for the evaluation of supraesophageal symptoms.

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records and the findings from endoscopy, esophageal manometry and ambulatory 24-h pH monitoring of an unselected group of consecutive patients who were referred to our motility laboratory from July, 2003 to December, 2006. A total of 632 patients received all three examinations due to supraesophageal symptoms (e.g. globus, hoarseness or cough). Of them, we selected the patients who had normal esophageal motility and a diagnosis of IEM. We did not enroll those patients who had a history of gastric surgery, a diagnosis of scleroderma or those who were on anti-reflux medications at the time of the study.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pusan National University Hospital.

The presence or absence of reflux esophagitis, hiatal hernia and endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia (ESEM) were determined by two endoscopists (G.H. Kim, G.A. Song).

Reflux esophagitis: If esophagitis was present, it was graded according to the Los Angeles classification[8].

Hiatal hernia: Hiatal hernia was defined as a circular extension of the gastric mucosa above the diaphragmatic hiatus greater than 2 cm in the axial length.

Endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia: The presence or absence of endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia (ESEM) was examined in the lower portion of the esophagus, including the esophagogastric junction, during inflation of the esophagus before inserting the endoscope into the stomach. The esophagogastric junction was defined as the oral side end of the fold, which exists continuously from the gastric lumen[9], as well as the end of the anal side of the fine longitudinal vessel, because the veins in the lower part of the esophagus were distributed uniformly, running parallel and longitudinally in the lamina propria[10,11]. The squamo-columnar junction was defined by a clear change in the color of the mucosa. ESEM was defined as the area between the squamo-columnar junction and the esophagogastric junction.

All antisecretory and prokinetic medications were discontinued at least 7 d before testing. Esophageal manometry was performed, after an overnight fast, with using an eight-lumen catheter (Synetics Medical Co., Stockholm, Sweden) with side holes 3 cm, 4 cm, 5 cm, 6 cm, 8 cm, 13 cm, 18 cm, and 23 cm from the catheter tip and a water-perfused, low-compliance perfusion system (Synetics Medical Co., Stockholm, Sweden), according to a standard protocol. Briefly, the manometry protocol included the following: First, a station pull-through was performed through the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to determine the end-expiratory resting pressure, the LES length and the location relative to the nares. The catheter was then positioned with the most distal side-hole 2 cm below the upper margin of the LES. Ten 5-mL water swallows were given to evaluate peristalsis; only the esophageal body contractions, measured at 3 cm, 8 cm and 13 cm above the LES, were recorded for data analysis. The catheter was then pulled through the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) in the same manner (station pull-through) to determine the resting UES pressure, the length and the location relative to the nares. Patients were identified as having IEM when the total sum of the low amplitude peristaltic contractions (the distal amplitude measured at 3 or 8 cm above the LES was < 30 mmHg) and the nontransmitted peristaltic contractions (dropouts at either 3 cm or 8 cm above the LES) was equal or greater than 30% of the total number of swallows used for the esophageal body study[4].

Ambulatory 24-h dual-probe pH monitoring was performed immediately after esophageal manometry with using a single-use monocrystalline antimony dual-site pH probe (Zinetics 24, Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, USA) with the electrodes placed at the tip and 15 cm proximal to the tip. A cutaneous reference electrode placed on the upper chest was also used. All the electrodes were calibrated in buffer solutions of pH 7 initially and then pH 1. The pH catheter was introduced transnasally into the stomach and it was withdrawn back into the esophagus until the electrodes were 5 cm above the proximal margin of the LES. The subjects were encouraged to eat regular meals with restriction for the intake of drink or food with a pH below 4. All the subjects recorded their meal times (start and end), body position (supine and upright) and any symptoms in a diary. The data were collected using a portable data logger (Digitrapper Mark III, Synetics Medical Co., Stockholm, Sweden) with a sampling rate of 4 seconds, and the data was then transferred to a computer for analysis using “Polygram for Windows®” (Release 2.04, Synetics Medical Co., Stockholm, Sweden). For both sites, a decrease in pH below 4, which was not induced by eating or drinking, was considered the beginning of a reflux episode, and the following rise to pH above 4 was considered the end of such an episode. To be accepted as a gastropharyngeal reflux event, the decrease at the proximal probe had to be abrupt and simultaneous with the decrease at the distal probe, or it was preceded by a decrease in pH of a similar or larger magnitude at the distal probe. Thus, acid episodes induced by oral intake, aero-digestive tract residue and secretions, proximal probe movement or loss of mucosal contact in which the proximal pH decline may precede the esophageal pH drop were not included as gastropharyngeal reflux episodes.

The variables assessed for gastroesophageal reflux at the distal probe were the total percentage of time the pH was < 4, the percentage of time the pH was < 4 in the supine and upright positions, the number of episodes the pH was < 4, the number of episodes the pH was < 4 for ≥ 5 min, the duration of the longest episode the pH was < 4 and the DeMeester composite score[12].

The variables assessed for gastropharyngeal reflux at the proximal probe were the total percentage of time the pH was < 4, the percentage of time the pH was < 4 in the supine and upright positions, and the number of episodes the pH was < 4.

For the diagnosis of GERD at the distal probe, two different aspects were analyzed[13,14]; (1) the total reflux time: the total proportion of the recorded time with pH < 4; a value of > 4% was considered abnormal; (2) the number of reflux episodes: the total number of pH episodes with pH< 4 during the recording; a value of > 35 episodes was considered abnormal.

For the diagnosis of gastropharyngeal reflux disease (GPRD) at the proximal probe, we considered more than 0.1% for the total time, 0.2% for the upright time and 0% for the supine time of pH < 4 to be pathological. For the number of reflux episodes, more than 4 reflux episodes were considered pathological[15,16].

The data are expressed as mean ± SE unless otherwise noted. The student t-test was used to assess the statistical significance of age, the body mass index, the pressure and length of the LES and the parameters of ambulatory pH monitoring between the two groups. The differences in gender, alcohol intake, smoking, typical reflux symptoms, indications for pH monitoring, reflux esophagitis, hiatal hernia, ESEM, GERD and GPRD, as defined by the ambulatory pH monitoring between the two groups were assessed using the χ2 test. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical calculations were performed using the SPSS version 12.0 for Windows software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

A total of 264 patients with normal esophageal motility and 195 patients with the diagnosis of IEM were included in this study. Age, gender, the body mass index, typical reflux symptoms and indications for pH monitoring were not different between the two groups. There was no difference in the frequency of reflux esophagitis and hiatal hernia between the two groups (Table 1).

The LES pressure was lower in the patients with IEM than in those patients with normal esophageal motility. All the variables showing gastroesophageal reflux at the distal probe were not different between the two groups. There was no difference in all the variables showing gastropharyngeal reflux at the proximal probe between the two groups (Table 2).

The frequency of GERD and GPRD, as defined by ambulatory pH monitoring was not different between the two groups (Table 3, Figure 1).

Esophageal acid clearance consists of two processes, first is rapid removal of most of the intraluminal refluxate, which is achieved by gravity and primary or secondary peristalsis (volume clearance), and this is followed by a slow neutralization of the acidified mucosa by the swallowed saliva (chemical clearance). Previous analysis of the relationship between peristaltic dysfunction and the efficacy of esophageal emptying, with using concurrent manometry and fluoroscopy, illustrated that absent or incomplete peristaltic contractions invariably resulted in little or no volume clearance and ineffective esophageal propulsion of a bolus occurs when the amplitude of the peristaltic waves is below 30 mmHg[17]. Thus, peristaltic dysfunction could potentially prolong esophageal acid clearance by delaying the first phase, that of esophageal emptying.

GERD motility abnormalities are part of the nonspecific motor disorders that have been described many years ago[18], and IEM has been found in 20%-50% of the patients with GERD[19]. In addition, there have been some studies suggesting a link between IEM and delayed esophageal acid clearance[3,5,20]. When GERD patients underwent pH monitoring, there were significantly more recumbent and upright reflux episodes and delayed acid clearance in the patients with IEM than in those patients without IEM[3,20]. A greater frequency of IEM was found in patients with respiratory presentations of GERD (chronic cough, asthma and laryngitis) and identification of IEM was particularly useful for patients with supraesophageal GERD[5].

In present study, we selected the patients who had normal esophageal motility and IEM among the patients who received the endoscopy, esophageal manometry and ambulatory pH monitoring due to supraesophageal symptoms. We then analyzed the degree of gastroesophageal and gastropharyngeal reflux in both group. Our results indicated that IEM was not associated with GPRD as well as GERD, as defined by ambulatory pH monitoring. In addition, all the variables for gastropharyngeal reflux and gastroesophageal reflux were not higher in the patients with IEM than those with normal esophageal motility. These findings are consistent with the previous studies[21,22] showing that there was no association between esophageal dysmotility and abnormal acid reflux in patients with supraesophageal GERD symptoms. We also examined the degree of gastroesophageal and gastropharyngeal reflux according to the severity of IEM, but there was no association (data not shown), which was similar to the previous report[23] showing that the severity of IEM was not different in erosive and in nonerosive GERD patients. These results suggest that IEM alone is unlikely to be the major determinant of abnormal esophageal acid exposure.

Although many studies have assessed the link between IEM and esophagitis, this issue remains controversial. Most of the previous studies restricted the enrolled subjects to the GERD patients. IEM was associated with reflux esophagitis in some studies of patients with confirmed GERD[6,24]. However, other studies showed that the presence of reflux esophagitis was similar between the patients with IEM and those patients with normal esophageal peristalsis[20] and there was no difference in the severity of IEM when comparing the erosive and non-erosive GERD patients[23]. In our present study, we included the patients who had normal esophageal motility and IEM over a defined period, providing that the ambulatory study had been done in the absence of anti-secretory therapy, thereby insuring the presence of a control group with normal esophageal acid exposure. Our result showed that reflux esophagitis was not associated with IEM.

There were some merits of this study when comparing it with the previous studies. First, in contrast to previous reports[5,21,22] that focused on an association between IEM and supraesophageal reflux disease, our study limited the enrolled subjects to patients with normal esophageal motility and those with IEM to maximize the effect of IEM on GPRD. Second, in the current analysis, we defined GERD and GPRD according to the strict criteria of ambulatory 24-h dual-probe pH monitoring, which is the best available test for diagnosing GPRD, as well as GERD[7]. Third, because all the patients in the current study underwent upper endoscopy, we were able to classify them according to the presence or absence of esophagitis and hiatal hernia.

There were some limitations in this study. First, the ambulatory pH monitoring is not 100% accurate and it has a sensitivity as low as 70% in patients with esophagitis, and the sensitivity is substantially lower in patients with nonerosive disease[25], so that some of our patients may have been misclassified. Yet, we included a large number of cases (459 cases), so this limitation was probably lessened. Second, a great deal of controversy exists about the location of the proximal probe. Recording the pH in the hypopharynx is technically difficult. Acid exposure in the hypopharynx can easily be missed because of the relatively large space within the hypopharynx[15]. On the contrary, placement of the proximal probe in or below the upper esophageal sphincter allows for more permanent contact with the mucosa during the 24-h period and this results in fewer artifacts[15,16]. We used a dual-site pH probe with electrodes placed at the tip and 15 cm proximal to the tip, and we could not choose the exact location of the proximal probe. Yet in most cases (75.4%, 346/459), the proximal probe was located in the UES. So, for the diagnosis of GPRD, we used the criteria proposed by Smit et al[15,16].

Why is IEM not associated with GPRD as well as GERD? Conventional manometry may be unable to evaluate the “true effectiveness” of esophageal peristalsis[26,27]. In addition, the refluxed acid is neutralized by both the esophageal submucosal secretions and the swallowed salivary secretions, so it becomes non-acid reflux material. Therefore, even though this non-acid refluxate in the upper level actually increased in the patients with IEM, the proximal pH probe cannot detect it. To solve this problem, a prospective study using a combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH measurement, which are able to detect both acid and non-acid reflux, as well as the proximal extent of the refluxate, will be needed.

In conclusion, by analyzing a large cohort of patients who had normal esophageal motility and IEM, we demonstrated that there was no correlation between IEM and GPRD, as well as between IEM and GERD, as defined by ambulatory pH monitoring. Although we do not completely exclude that such an association may be possible, IEM alone cannot be considered a definitive marker for reflux (gastroesophageal or gastropharyngeal).

Ineffective esophageal motility (IEM) is associated with an increased acid clearance times in the distal esophagus. Gastropharyngeal reflux causes supraesophageal manifestations such as globus, chronic cough, hoarseness, asthma, chronic sinusitis, or other otorhinolaryngologic diseases. It might be hypothesized that patients with IEM would be unable to clear refluxed acid; this would lead to a prolonged esophageal dwell time of the refluxed acid and then the refluxed acid would reach to a higher level. As a result, it would be presumed that patients with IEM have more gastropharyngeal reflux than those patients with normal esophageal motility.

The research front in this area is focused on evaluating the association of IEM and gastropharyngeal reflux disease (GPRD), as well as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Although many studies have assessed the link between IEM and esophagitis, this issue remains controversial. Most of the previous studies restricted the enrolled subjects to GERD patients. IEM was associated with reflux esophagitis in some studies of patients with confirmed GERD. However, other studies showed that the presence of reflux esophagitis was similar between the patients with IEM and those patients with normal esophageal peristalsis. This study showed no association between IEM and GPRD, as well as between IEM and GERD in a large series of patients who underwent ambulatory 24-hour dual-probe pH monitoring, for the evaluation of supraesophageal symptoms.

There are few reports on the association between IEM and GPRD. Most previous studies are symptom-based and lack objective tests such as ambulatory 24-h dual-probe pH monitoring. This study is the largest study to evaluate the association of IEM and GPRD in patients who underwent ambulatory 24-h dual-probe pH monitoring for the evaluation of supraesophageal symptoms.

IEM is not associated with GPRD, as well as GERD. Further studies using a combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH measurement, which are able to detect both acid and non-acid reflux, as well as the proximal extent of the refluxate, will be needed.

Ineffective esophageal motility (IEM) is defined as contractions with an amplitude of less than 30 mmHg and/or with a rate of nontransmission to the distal esophagus in number of 30% or more of water swallows. Esophageal acid reflux into the laryngeal and pharyngeal areas causes extraesophageal manifestations such as chronic cough, hoarseness, asthma, globus sensation, chronic sinusitis, or other otorhinolaryngologic diseases. This condition is called as gastropharyngeal reflux disease (GPRD).

This is an interesting study since physicians who perform esophageal manometry frequently find IEM. This study is well structured and definitions of esophagitis, GERD and GPRD are adequate since they were based on endoscopy and 24-h dual esophageal pH monitoring.

Peer reviewers: Diego Garcia-Compean, MD, Professor, Faculty of Medicine, University Hospital, Department of Gastroenterology, Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon, Ave Madero y Gonzalitos, 64700 Monterrey, N.L.Mexico; Fabio Pace, Professor, Division of Gastroenterology, “L. Sacco” University Hospital, University of Milan, Via G. B. Grassi, 74, Milano 20157, Italy

S- Editor Xiao LL L- Editor Rippe RA E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Dodds WJ, Dent J, Hogan WJ, Helm JF, Hauser R, Patel GK, Egide MS. Mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1547-1552. |

| 2. | Orlando RC. Overview of the mechanisms of gastro-esophageal reflux. Am J Med. 2001;111 Suppl 8A:174S-177S. |

| 3. | Leite LP, Johnston BT, Barrett J, Castell JA, Castell DO. Ineffective esophageal motility (IEM): the primary finding in patients with nonspecific esophageal motility disorder. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1859-1865. |

| 4. | Spechler SJ, Castell DO. Classification of oesophageal motility abnormalities. Gut. 2001;49:145-151. |

| 5. | Fouad YM, Katz PO, Hatlebakk JG, Castell DO. Ineffective esophageal motility: the most common motility abnormality in patients with GERD-associated respiratory symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1464-1467. |

| 6. | Diener U, Patti MG, Molena D, Fisichella PM, Way LW. Esophageal dysmotility and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:260-265. |

| 7. | Dobhan R, Castell DO. Normal and abnormal proximal esophageal acid exposure: results of ambulatory dual-probe pH monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:25-29. |

| 8. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. |

| 9. | Nandurkar S, Talley NJ. Barrett's esophagus: the long and the short of it. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:30-40. |

| 10. | Vianna A, Hayes PC, Moscoso G, Driver M, Portmann B, Westaby D, Williams R. Normal venous circulation of the gastroesophageal junction. A route to understanding varices. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:876-889. |

| 11. | Noda T. Angioarchitectural study of esophageal varices. With special reference to variceal rupture. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1984;404:381-392. |

| 12. | Johnson LF, DeMeester TR. Development of the 24-hour intraesophageal pH monitoring composite scoring system. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8 Suppl 1:52-58. |

| 13. | Johnsson F, Joelsson B, Isberg PE. Ambulatory 24 hour intraesophageal pH-monitoring in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 1987;28:1145-1150. |

| 14. | Weusten BLAM, Smout AJPM. Ambulatory monitoring of esophageal pH and pressure. The Esophagus. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2004; 135-150. |

| 15. | Smit CF, Mathus-Vliegen LM, Devriese PP, Schouwenburg PF, Kupperman D. Diagnosis and consequences of gastropharyngeal reflux. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2000;25:440-455. |

| 16. | Smit CF, Tan J, Devriese PP, Mathus-Vliegen LM, Brandsen M, Schouwenburg PF. Ambulatory pH measurements at the upper esophageal sphincter. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:299-302. |

| 17. | Kahrilas PJ, Dodds WJ, Hogan WJ. Effect of peristaltic dysfunction on esophageal volume clearance. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:73-80. |

| 18. | Richter JE, Wu WC, Johns DN, Blackwell JN, Nelson JL 3rd, Castell JA, Castell DO. Esophageal manometry in 95 healthy adult volunteers. Variability of pressures with age and frequency of "abnormal" contractions. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:583-592. |

| 19. | Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE. Ineffective esophageal motility does not equate to GERD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:715-717. |

| 20. | Ho SC, Chang CS, Wu CY, Chen GH. Ineffective esophageal motility is a primary motility disorder in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:652-656. |

| 21. | Vinjirayer E, Gonzalez B, Brensinger C, Bracy N, Obelmejias R, Katzka DA, Metz DC. Ineffective motility is not a marker for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:771-776. |

| 22. | Knight RE, Wells JR, Parrish RS. Esophageal dysmotility as an important co-factor in extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1462-1466. |

| 23. | Lemme EM, Abrahao-Junior LJ, Manhaes Y, Shechter R, Carvalho BB, Alvariz A. Ineffective esophageal motility in gastroesophageal erosive reflux disease and in nonerosive reflux disease: are they different? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:224-227. |

| 24. | Fornari F, Callegari-Jacques SM, Scussel PJ, Madalosso LF, Barros EF, Barros SG. Is ineffective oesophageal motility associated with reflux oesophagitis? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:783-787. |

| 25. | Kahrilas PJ, Quigley EM. Clinical esophageal pH recording: a technical review for practice guideline development. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1982-1996. |

| 26. | Simren M, Silny J, Holloway R, Tack J, Janssens J, Sifrim D. Relevance of ineffective oesophageal motility during oesophageal acid clearance. Gut. 2003;52:784-790. |

| 27. | Tutuian R, Castell DO. Esophageal function testing: role of combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and manometry. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2005;15:265-275. |