Published online Oct 14, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5920

Revised: September 4, 2008

Accepted: September 11, 2008

Published online: October 14, 2008

We report an unusual pathological entity of a pseudoaneurysm of the right hepatic artery, which developed two years after the resection of a type II hilar cholangiocarcinoma and secondary to an excessive skeletonization for regional lymphadenectomy and neoadjuvant external-beam radiotherapy. After a sudden and massive hematemesis, a multidetector computed tomographic angiography (MDCTA) showed a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm. Angiography with embolization of the pseudoaneurysm was attempted using microcoils with adequate patency of the hepatic artery and the occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm. A new episode of hematemesis 3 wk later revealed a partial revascularization of the pseudoaneurysm. A definitive interventional radiological treatment consisting of transarterial embolization (TAE) of the right hepatic artery with stainless steel coils and polyvinyl alcohol particles was effective and well-tolerated with normal liver function tests and without signs of liver infarction.

- Citation: Briceño J, Naranjo &, Ciria R, Sánchez-Hidalgo JM, Zurera L, López-Cillero P. Late hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: A rare complication after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(38): 5920-5923

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i38/5920.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.5920

Bleeding from a pseudoaneurysm of major visceral arteries as a result of an adjacent septic condition or an intraoperative injury may lead to a troublesome emergency. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm can result in hemorrhage into the biliary tract when an abnormal communication is established between the vessel and the bile duct. Degeneration and weakness of hepatic arterial wall can be secondary to a trauma (accidental or iatrogenic) or an inflammation of the biliary tract [1,2]. A mechanical injury of the artery during operation, mainly due to lymph node dissection for malignancy, may be a clear predisposing factor for delayed arterial bleeding after hepatobiliary surgery.

We report an unusual pathological entity of a pseudoaneurysm of the right hepatic artery, which developed two years after the resection of a type II hilar cholangiocarcinoma. This resulted in catastrophic upper gastrointestinal bleeding, which was ultimately treated by an aggressive combination of interventional radiological procedures.

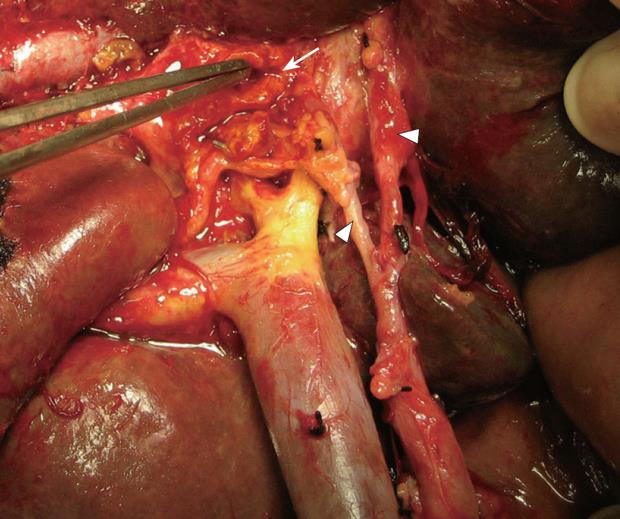

A 78-year-old man with cholangiocarcinoma involving the proximal bile ducts (hilar cholangiocarcinoma or Klatskin tumor) was referred for surgical treatment in July 2005. Abdominal pain, discomfort, anorexia, weight loss, pruritus and jaundice with bilirubin of 18 mg/dL were the main symptoms. After a magnetic resonance imaging cholangiography, the patient was diagnosed as having a type II cholangiocarcinoma (Bismuth-Corlette modified classification) without invasion of main portal vein, the proper hepatic artery or its branches[3] and a preoperative stage IB, according to AJCC staging system (T2N0M0). Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage and subsequent placement of a temporary endoprosthesis were performed prior to resection. A standard extrahepatic biliary tract excision associated with segment I resection was performed through an inverted T-incision. Skeletonization for regional lymphadenectomy with removal of neural and lymphoid tissues from hepatoduodenal ligament and liver hilus was also added (R0 resection) (Figure 1). Bilio-enteric continuity was restored by hepatojejunostomy to a Roux-en-Y loop of jejunum. Three duct orifices (right, left and segment I bile ducts) were anastomosed. The pathological result of the lymphadenectomy revealed metastases to two perihilar lymph nodes (N1). The postoperative stage was IIB (T2N1M0). The patient was discharged 11 d later without complications. Adjuvant therapy consisted of a gemcitabine-based regimen (1000 mg/m2 as a 30-min infusion every 2 wk until achieving 6 treatment cycles) combined with conventional external-beam radiotherapy (5000 cGy given with an equivalent total dose in a 200 cGy/25 fractions). The time interval between operation and before starting chemo-radiotherapy was 6 wk.

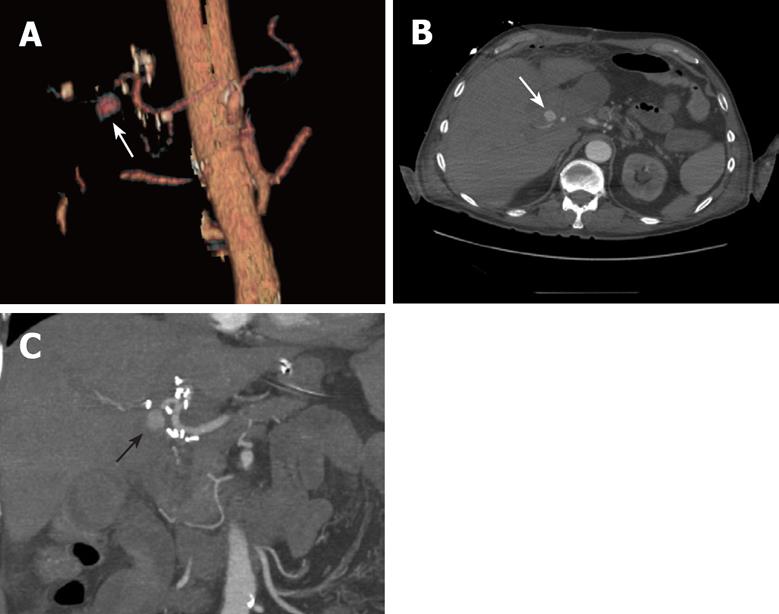

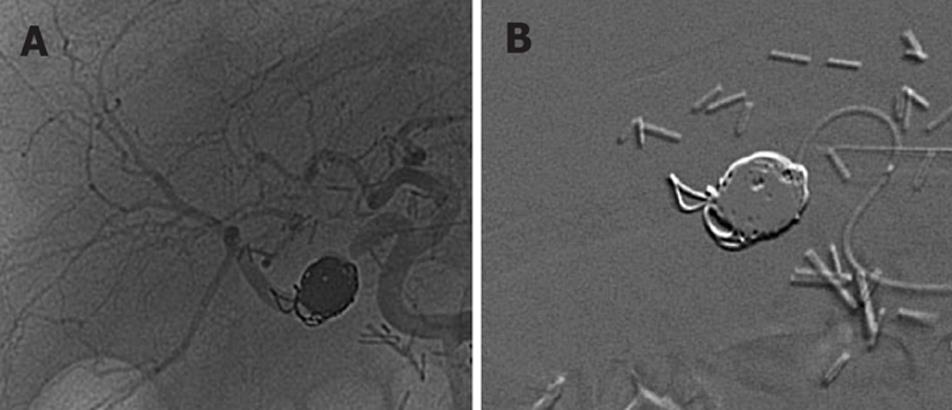

In October 2007, the patient developed a transient minor gastrointestinal bleeding without hemodynamic repercussion and an upper digestive endoscopy disclosed no evidence of gastroduodenal bleeding. Ten days later, the patient was readmitted because of a sudden and massive hematemesis, causing hypovolemia and shock. After an initial resuscitation in ICU, hemodynamic stability was achieved. An upper digestive endoscopy only revealed an hemorrhage from the Y-limb jejunum. A multidetector computed tomographic angiography (MDCTA) was performed with a multidetector 16-row computed tomography scanner. Arterial phase images were obtained after intravenous injection of 150 mL of contrast material at a rate of 4 mL/s using the bolus triggering technique (Figure 2)[4]. This technique precisely detected a large pseudoaneurysm originating from the right hepatic artery. Angiography was carried out immediately with a 4 Fr. catheter. Contrast was seen jetting into the aneurysm, but no communication with the intestine could be proven. Embolization of the pseudoaneurysm was attempted using microcoils to stop the inflow into the pseudoaneurysmal lumen. Patency of the hepatic artery and its branches, and the occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm were confirmed (Figure 3). The patient was discharged in acceptable clinical condition with an uneventfully outcome.

Three weeks later, the patient suffered from a new episode of hematemesis, requiring readmission and supportive treatment. A new angiography displayed a partial revascularization of the pseudoaneurysm (Figure 4A). A definitive interventional radiological treatment was decided, consisting of transarterial embolization (TAE) of the right hepatic artery with stainless steel coils and polyvinyl alcohol particles (Figure 4B). Liver function tests were normal, with a transient elevation of transaminases. Embolization of the complete right hepatic artery was well-tolerated, without signs of liver infarction. The patient is in good clinical condition 5 mo after this last procedure.

Three major predisposing factors for delayed arterial bleeding after hepatobiliary surgery have been suggested[1]: (1) digestion of hepatic arterial wall due to infectious bile from anastomotic leakage; (2) arterial irritation by localized abscess in the inferior hepatic space; and (3) a mechanical injury of the artery during operation, mainly due to lymph node dissection for malignancy. The result is the formation of an arterial sac with a possible rupture into the biliary tract, and consequently, hemobilia. Surgery of the biliary tract may damage the hepatic artery by the dissection or suture, which may result in an arteriobiliary fistula or in a false aneurysm eroding into the extrahepatic bile ducts[5]. When a patient develops bleeding 1 or 2 wk after surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma, especially when the event is sudden in onset with hemobilia, arterial injury should be suspected. However, a late catastrophic bleeding requiring life-supporting treatment is unusual after surgery for Klatskin tumor. To our knowledge, there is only one case reported by Siablis et al[6] in which a hemobilia secondary to hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm after a resected IIIb Klatskin tumor appeared two years later due to a nearby biloma. In the absence of previous biliary leakage, we propose different explanations for the etiology of artery pseudoaneurysm in the present case report: (1) an excessive skeletonization for regional lymphadenectomy with removal of neural and lymphoid tissues; and (2) postoperative external-beam radiotherapy. Usually, the vasculature is injured by skeletonization for lymphadenectomy during radical surgery and too-tight ligation around the arterial conduit[7,8]. External radiotherapy may cause a degeneration of the arterial media. These two factors, alone or associated, can cause an iatrogenic trauma of the hepatic artery wall and, subsequently, the development of a false arterial sac. Another factor may be the short time interval between operation and before starting chemo-radiotherapy (6 wk), which probably contributed to the pre-existing vessel trauma and affecting optimal wound healing. However, the presence of positive lymph nodes suggested a more advanced disease than planned preoperatively and, consequently; chemo-radiotherapy was administered promptly after surgery in this patient.

MDCTA is a non-invasive modality to select patients who must be treated with angiographic intervention or surgery[4]. This technique is better than conventional contrasted-tomography and shows a good correlation with digital subtraction angiography. A sentinel bleeding as a precursor of vessel erosion after biliary surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma may lead to a prompt diagnosis preferentially with MDCTA. We cannot ascertain whether the GI bleeding was coming from an arterio-enteric or an arterio-bilial fistula. However, as shown in Figure 4A, a partial enteric migration of microcoils after the first and selective embolization suggests an arterio-enteric fistula origin.

In the setting of a prior complex bilio-enteric surgery, a new open surgical approach is not recommended because re-entering the previous scarred operative field for repair and hemostasis by suturing hepatic artery or placing a new conduit graft to restore circulation is too difficult and dangerous. Interventional radiology with selective embolization of pseudoanerysm is a safe and a definitive treatment in most of the cases. Angiographic embolization should be performed proximal and distal to the origin of the pseudoaneurysm rather than proceeding with embolization into the pseudoaneurysm cavity[7,9]. Newer technology detachable coils developed for neurovascular procedures may play a role in occluding pseudoaneurysms. These coils are placed into the pseudoaneurysm through microcatheters. Once they are placed in position adequately filling the space needed and stable, they can be released by a low voltage electric charge through the attachment wire. If the radiologist is not satisfied with coil placement or if the distal flow is compromised it can simply be withdrawn without detachment[10].

The best procedure after microcoil-embolization failure is not clear. Some authors suggest good results by placing covered grafts to secure hepatic arterial flow, guiding the blood flow into the proper direction out of the pseudoaneurysmal lumen, avoiding the possibility of interfering with arterial flow to the liver[11-15]. Nonetheless, the dual blood supply to the liver makes it extremely tolerant of arterial occlusion for haemostasis. Indeed, the compensatory arterial circulation to the liver after arterial ligation for the treatment of ruptured hepatic artery has been recognized by Michels et al[16]. At least 26 possible routes of collateral arterial blood supply to the liver from the common hepatic trunk were described. The main collateral pathways to the liver after TAE included the right inferior phrenic artery, the aberrant left hepatic artery and the intrahepatic communicating branches. The main vascular collateral pathways in the liver may be reliable in an “undisturbed or virgin liver”. In post-resection, where the liver may have undergone extensive mobilization, these collaterals may have been disrupted and may be unreliable. However, we performed the procedure without this extensive mobilization of the liver, maintaining the native ligaments of the liver and only mobilizing perihilar and hilar tissues. Phrenic arteries and intrahepatic communicating branches were well preserved. In any case, complete hepatic occlusion cannot be a standard approach, and it has only place as an extreme solution for an extremely urgent patient with selective embolization failure and/or a high-risky surgical intervention. In this setting, TAE on the hepatic artery has generally been considered to be relatively safe if the portal blood flow is preserved.

Peer reviewer: Chao-Long Chen, Professor, Department of Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical Centre, 123, Taipei Rd, Niao Sung Hsiang, Kaohsiung Hsien 83305, Taiwan, China

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Yin DH

| 1. | Okuno A, Miyazaki M, Ito H, Ambiru S, Yoshidome H, Shimizu H, Nakagawa K, Shimizu Y, Nukui Y, Nakajima N. Nonsurgical management of ruptured pseudoaneurysm in patients with hepatobiliary pancreatic diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1067-1071. |

| 3. | Bismuth H, Nakache R, Diamond T. Management strategies in resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1992;215:31-38. |

| 4. | Kayahan Ulu EM, Coskun M, Ozbek O, Tutar NU, Ozturk A, Aytekin C, Haberal M. Accuracy of multidetector computed tomographic angiography for detecting hepatic artery complications after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:3239-3244. |

| 5. | Kelley CJ, Hemingway AP, Mcpherson GA, Allison DJ, Blumgart LH. Non-surgical management of post-cholecystectomy haemobilia. Br J Surg. 1983;70:502-504. |

| 6. | Siablis D, Papathanassiou ZG, Karnabatidis D, Christeas N, Vagianos C. Hemobilia secondary to hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm: an unusual complication of bile leakage in a patient with a history of a resected IIIb Klatskin tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5229-5231. |

| 7. | Yamashita Y, Taketomi A, Fukuzawa K, Tsujita E, Harimoto N, Kitagawa D, Kuroda Y, Kayashima H, Wakasugi K, Maehara Y. Risk factors for and management of delayed intraperitoneal hemorrhage after pancreatic and biliary surgery. Am J Surg. 2007;193:454-459. |

| 8. | Abbas MA, Fowl RJ, Stone WM, Panneton JM, Oldenburg WA, Bower TC, Cherry KJ, Gloviczki P. Hepatic artery aneurysm: factors that predict complications. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:41-45. |

| 9. | Reber PU, Baer HU, Patel AG, Wildi S, Triller J, Büchler MW. Superselective microcoil embolization: treatment of choice in high-risk patients with extrahepatic pseudoaneurysms of the hepatic arteries. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:325-330. |

| 10. | Amesur NB, Zajko AB. Interventional radiology in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:330-351. |

| 11. | Ichihara T, Sato T, Miyazawa H, Shibata S, Hashimoto M, Ishiyama K, Yamamoto Y. Stent placement is effective on both postoperative hepatic arterial pseudoaneurysm and subsequent portal vein stricture: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:970-972. |

| 12. | Maleux G, Pirenne J, Aerts R, Nevens F. Case report: hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm after liver transplantation: definitive treatment with a stent-graft after failed coil embolisation. Br J Radiol. 2005;78:453-456. |

| 13. | Sachdev U, Baril DT, Ellozy SH, Lookstein RA, Silverberg D, Jacobs TS, Carroccio A, Teodorescu VJ, Marin ML. Management of aneurysms involving branches of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries: a comparison of surgical and endovascular therapy. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:718-724. |

| 14. | Tulsyan N, Kashyap VS, Greenberg RK, Sarac TP, Clair DG, Pierce G, Ouriel K. The endovascular management of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:276-283; discussion 283. |

| 15. | Rami P, Williams D, Forauer A, Cwikiel W. Stent-graft treatment of patients with acute bleeding from hepatic artery branches. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28:153-158. |