Published online Sep 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5471

Revised: July 28, 2008

Accepted: August 3, 2008

Published online: September 21, 2008

Piodermal gangrenosum (PG) is an uncommon ulcerative cutaneous dermatosis associated with a variety of systemic diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), arthritis, leukaemia, hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis. Other cutaneous ulceration resembling PG had been described in literature. There has been neither laboratory finding nor histological feature diagnostic of PG, and diagnosis of PG is mainly made based on the exclusion criteria. We present here a patient, with ulcerative colitis (UC) who was referred to the emergency section with a large and rapidly evolving cutaneous ulceration. Laboratory and microbiological investigation associated with histological findings of the ulcer specimen allowed us to exclude autoimmune and systemic diseases as well as immuno-proliferative disorders. An atypical presentation of PG with UC was diagnosed. Pulse boluses of i.v. methyl-prednisolone were started, and after tapering steroids, complete resolution of the skin lesion was achieved in 3 wk. The unusual rapid healing of the skin ulceration with steroid mono-therapy and the atypical cutaneous presentation in this patient as well as the risk of misdiagnosis of PG in the clinical practice were discussed.

- Citation: Aseni P, Sandro SD, Mihaylov P, Lamperti L, Carlis LGD. Atypical presentation of pioderma gangrenosum complicating ulcerative colitis: Rapid disappearance with methylprednisolone. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(35): 5471-5473

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i35/5471.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.5471

Piodermal gangrenosum (PG) is an uncommon ulcera-tive cutaneous dermatosis associated with a variety of systemic conditions including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), arthritis, haematological malignancies, paraproteinemia and hepatitis[1-5]. Many other cutaneous ulcerations resembling PG have been described in literature[6-10]. There has been neither laboratory finding nor histological feature diagnostic of PG, and diagnosis of PG is mainly established by exclusion criteria. We described here a patient with ulcerative colitis (UC) who manifested atypical presentation of PG. After diagnosis, a rapid healing of the large and painful skin ulceration was obtained by high doses of i.v. steroid therapy.

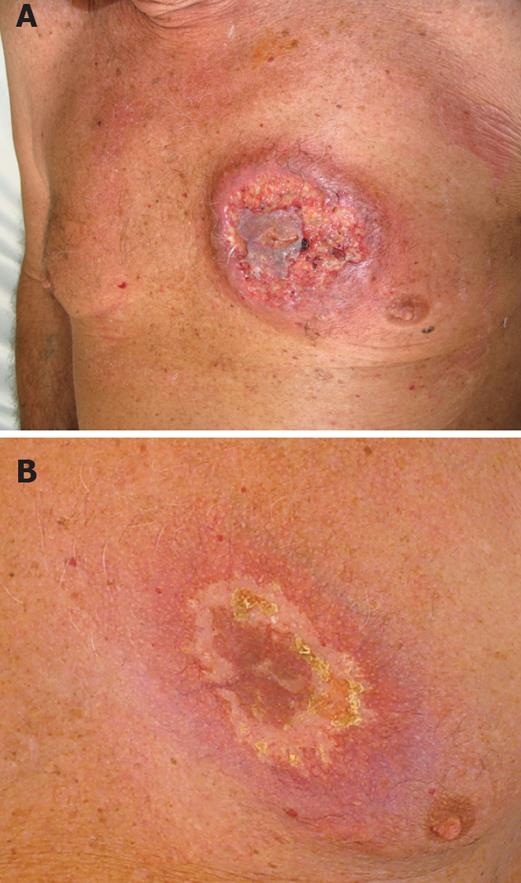

An 82-year-old man was referred to the emergency section with a round painful cutaneous ulcer of 15 cm in diameter in the left mammary region. The edges were undermined and presented with granulated tissues, crusts, and purulent exudates (Figure 1A). One month before a lesion appeared in the same skin area presenting as a small red plaque with surrounding erythema. This was supposed to be a consequence of a mosquito bite according to his family doctor. The lesion rapidly progressed to a wider and painful cutaneous ulceration over the past month. Antimicrobial treatment with amoxicillin and ciprofloxacin was totally ineffective and the patient required paracetamol and codeine every 6 h for pain relief.

The patient was admitted to our hospital 3 years before due to rectal bleeding and anaemia. UC was diagnosed. Therefore, the patient received prednisone and mesalazine therapy (10 mg/d and 800 mg thrice/d, respectively). Prednisone was tapered and stopped after 3 mo, whereas mesalazine administration was continued.

On examination, the patient presented with mild hyperthermia (37.5-38°C). He complained of 3-5 daily episodes of diarrhoea but without rectal bleeding. No lymphadenopathy was observed. The lesion was very painful. A swab and microbiological examination of the specimen from the ulcer was negative for bacteria and fungi. Routine laboratory investigations revealed white cell count of 13.8 × 109/L with neutrophilia. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 32 mm/h. Liver and kidney function tests, immunoglobulin, protein electrophoresis, anticoagulation panel were normal. Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test, HIV test, anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic, antinuclear and anti-DNA antibodies, rheumatoid factor, LE test, were all negative, and cryoglobulins were absent.

Chest X-ray, venous and arterial functional studies were normal. A skin biopsy of the lesion was performed under local anaesthesia. Histological analysis showed focal necrotizing flogosis associated with ulceration and peripheral lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltration extending through the dermis and subcutaneous tissue; extravascular red blood cell infiltration was also present.

Necrotizing vasculitis was not observed and the histological changes were consistent with pioderma gangrenosum. Methylprednisolone pulse boluses (500 mg/d for 3 d) were given i.v. Steroid was reduced to 80 mg/d and then tapered to 20 mg/d for 3 wk. The patient healed from skin lesion 20 d after beginning of steroid therapy (Figure 1B).

Brunsting et al[11] in 1930 first described five patients with rapidly progressive and painful suppurative skin ulceration with necrotic and undermined borders that were called PG. This lesion is a neutrophilic dermatosis associated with a variety of systemic diseases, such as paraproteinemia, arthritis, and myeloproliferative diseases, and IBD. In about 50% of the cases, UC is the underlying condition and PG may parallel the severity of the disease[1,9,12]. The pathogenesis of PG is poorly understood and over-expression of interleukin (IL)-8 and IL-16 has been reported, suggesting an over-reactive inflammatory response to a traumatic process. Although the lesion can occur in any surface it is more common on the legs in perineal, vulvar, penile and neck region. Atypical presentations are considered on the arms or in the chest. Weenig et al[6] reported two cases of livedoid vasculopathy, a rare thrombo-occlusive disease of post-capillary venules, which may occur with cutaneous ulcers of the legs characterized by a very similar macroscopic and histological pattern. These lesions may be confused with PG. However, livedoid vasculopathy is not responsive to steroid therapy. Therefore, PG is an excluded diagnosis on the basis of laboratory findings and histology, associated with a high rate of clinical suspicion. The good and rapid clinical responses to steroids associated with other immunosuppressive therapy such as cyclosporine, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide are also important “ex-adiuvantibus” criteria.

Patients with vasculitis associated with or not associated with cryoglobulinemia or those with antiphospholipid-antibody syndrome, and those with Wegener granulomatosis and polyartrite nodosa, may present lesions resembling PG[5,6,8,9,13]. These lesions may be misdiagnosed with PG due to initial response to steroid therapy, but without evidence of complete healing. The clinical pattern of a patient with very painful skin lesion, suffering from IBD should raise the suspicion of PG; however laboratory findings and functional and radiologic analysis to rule out other systemic disease are mandatory for a correct diagnosis.

Other rare malignant lesions, such as lymphoma, leukaemia cutis and Langherans cell histiocytosis can be ruled out according to the histological studies of the specimen.

PG is a diagnosis of exclusion and its misdiagnosis can result in serious clinical consequences.

The chronic UC in our patient based on the exclusion criteria, convinced us to start therapy with a high dose of corticosteroid. The rapid healing of such a large skin lesion is unusual. Some patients refractory to steroid treatment can benefit from the combination of steroid with cyclosporine[14,15]. At the moment, our patient is disease free at 12 mo after diagnosis without clinical symptoms related to UC under a maintenance therapy of 7.5 mg/d prednisone.

Peer reviewer: Alastair JM Watson, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, University of Liverpool, the Henry Wellcome Laboratory, Nuffield Bldg, Crown St, Liverpool L69 3GE, United Kingdom

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Callen JP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. The Lancet. 1998;351:581-585. |

| 2. | Powell FC, Su WP, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: classification and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:395-409; quiz 410-412. |

| 3. | Levitt MD, Ritchie JK, Lennard-Jones JE, Phillips RK. Pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Surg. 1991;78:676-678. |

| 4. | Neesse A, Michl P, Kunsch S, Ellenrieder V, Gress TM, Steinkamp M. Simultaneous onset of ulcerative colitis and disseminated pyoderma gangrenosum. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2007;1:110-115. |

| 5. | Smith JB, Shenefelt PD, Soto O, Valeriano J. Pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with cryoglobulinemia and hepatitis C successfully treated with interferon alfa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:901-903. |

| 6. | Weenig RH, Davis MD, Dahl PR, Su WP. Skin ulcers misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1412-1418. |

| 7. | Hay CR, Messenger AG, Cotton DW, Bleehen SS, Winfield DA. Atypical bullous pyoderma gangrenosum associated with myeloid malignancies. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:387-392. |

| 8. | Schlesinger IH, Farber GA. Cutaneous ulceration resembling pyoderma gangrenosum in the primary antiphospholipid syndrome: a report of two additional cases and review of the literature. J La State Med Soc. 1995;147:357-361. |

| 9. | Norris JF, Marshall TL, Byrne JP. Histiocytosis X in an adult mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1984;9:388-392. |

| 10. | Papi M, Didona B, De Pita O, Frezzolini A, Di Giulio S, De Matteis W, Del Principe D, Cavalieri R. Livedo vasculopathy vs small vessel cutaneous vasculitis: cytokine and platelet P-selectin studies. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:447-452. |

| 11. | Brunsting LA, Undewood LJ. Pyoderma vegetans in association with chronic ulcerative colitis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1949;60:161-172. |

| 12. | Gibson LE, Daoud MS, Muller SA, Perry HO. Malignant pyodermas revisited. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:734-736. |

| 13. | Nguyen KH, Miller JJ, Helm KF. Case reports and a review of the literature on ulcers mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:84-94. |

| 14. | Futami H, Kodaira M, Furuta T, Hanai H, Kaneko E. Pyoderma gangrenosum complicating ulcerative colitis: Successful treatment with methylprednisolone pulse therapy and cyclosporine. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:408-411. |

| 15. | Reichrath J, Bens G, Bonowitz A, Tilgen W. Treatment recommendations for pyoderma gangrenosum: an evidence-based review of the literature based on more than 350 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:273-283. |