Published online Sep 14, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5336

Revised: August 25, 2008

Accepted: September 2, 2008

Published online: September 14, 2008

AIM: To integrate results from different studies in examining the effectiveness of music in reducing the procedure time and the amount of sedation used during colonoscopic procedure.

METHODS: An electronic search in various databases was performed to identify related articles. Study quality was evaluated by the Jadad’s scale. The random effect model was used to pool the effect from individual trials and the Cohen Q-statistic was used to determine heterogeneity. Egger’s regression was used to detect publication bias.

RESULTS: Eight studies with 722 subjects were included in this meta-analysis. The combined mean difference for the time taken for the colonoscopy procedure between the music and control groups was -2.84 with 95% CI (-5.61 to -0.08), implying a short time for the music group. The combined mean difference for the use of sedation was -0.46 with 95%CI (-0.91 to -0.01), showing a significant reduction in the use of sedation in the music group. Heterogeneity was observed in both analyses but no publication bias was detected.

CONCLUSION: Listening to music is effective in reducing procedure time and amount of sedation during colonoscopy and should be promoted.

- Citation: Tam WW, Wong EL, Twinn SF. Effect of music on procedure time and sedation during colonoscopy: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(34): 5336-5343

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i34/5336.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.5336

| Study | Design | Baseline characteristic | Comparison group | Outcome |

| Andrada et al (2004)[35] | RCT | Intervention-31 males 32 females, mean age: 46 (14.22) | Intervention- Listening music until the end of procedure (classical tracts) | Blood pressure, capillary and oxygen saturation, heart rate level of anxiety |

| Control-28 males 27 females, mean age: 49 (13.88) | Control- Usual colonoscopy screening | |||

| Bechtold et al (2006)[36] | RCT | Intervention-41 males and 44 females, age: 58.5 | Intervention- Playing music upon the entrance the patient (same music for all patients) | Dose consumed, time to time, reach cecum, total procedure insertion difficulty scale, experience scale, pain scale, want music next time |

| Control-42 males 39 females, age: 54.1 | Control-50 mg of meperidine and 1 or 2 mg of midazolam | |||

| Harikumar et al (2006)[38] | RCT | Intervention-38 (male + female), age 15 - 60 | Intervention- Listening music (popular film songs based on classical rages, classical music, devotional songs, folk songs, soft instrumental music, and bioacoustics | Pain score, discomfort score, procedure time, recovery time, dose consumed |

| Control-40 (male + female), age 15-60 | Control-2 mg intravenous boluses of midazolam on demand; Colonoscopic procedure performed by endoscopists with experience of performing at least 200 full-length colonoscopic procedure | |||

| Lee et al (2002)[41] | RCT | Intervention 1-33 male 22 female | Intervention 1-Patient-controlled sedation | Dose of propofol, pain score, satisfactory score, willingness to repeat the same mode of sedation. |

| Inter-quartile age range: 46-68 mean age: 54 | ||||

| Intervention 2-29 male 26 female, | Intervention 2-Patient-controlled sedation+ music1 | |||

| Inter-quartile age range: 39-67 mean age: 47 | ||||

| Intervention 3-27 males 28 females, | Intervention 3- Music1 | |||

| Inter-quartile age range: 40-65 mean age: 51 | Could request intravenous administration of diazemuls (0.1 mg/kg) and meperidine (0.5 mg/kg) | |||

| Nasal oxygen (2 L/min) to all patients in the study | ||||

| 1Type of music: classical, jazz, popular (Chinese and English) and Chinese opera | ||||

| Examination performed endoscopists having more than 300 similar procedures before | ||||

| Ovayolu (2006)[42] | RCT | Intervention-14 males 16 females, age: 20-39 (n = 10), 40-59 (n = 11), 60 or above (n = 9) | Intervention- Listening music (classical Turkish music, a slow and relaxing music) | Dose of sedation consumed, anxiety score, pain score, VAS score, willingness to the procedure score and satisfaction score. |

| Control-14 males 16 females, age: 20-39 (n = 5), 40-59 (n = 11), 60 or above (n = 14) | Control- Usual colonoscopy screening; procedure performed by an expert endoscopist with experience of performing at least 200 full-length procedure previously | |||

| Schimann et al (2002)[44] | RCT | Intervention-25 males 34 females, mean age: 52.3 (13.9), | Intervention- Music from radio | Request of sedation (midazolam), oxygen supplement, procedure time |

| Control-33 males 27 females, mean age: 55.8 (13.5) | Control- Conventional procedure | |||

| Smolen et al (2002)[45] | RCT | Intervention-10 male 6 females, mean age: 58.83 (13.64) | Intervention-Listening music (classical, jazz, pop rock and easy listening) | Sedation, anxiety and heart rate |

| Control-7 males 9 females, mean age: 61.06 (9.48) | Control-Undergo standard colonoscopy procedure including explanation of the procedure by the nurse; receive a standard pre-procedure sedation consisting of a slow intravenous injection of 1 mg of midazolam in combination with 50 mg of meperidine | |||

| Uedo et al (2004)[46] | Intervention-7 males 7 females, mean age: 54 (6) | Intervention- Listen the music (easy listening style) from the beginning and during procedure | Salivart cortisol levels | |

| Control-11 males 4 females, mean age: 54 (8) | Control- Usual procedure for undergoing colonoscopy, no anxiolytic medications, no antisecretory agents |

| Study (year of publication) | Is the study randomized? | Is the procedure appropriate & reported? | Is the study blind to the assessors? | Is the blinding method appropriate & reported? | Were the groups similar at baseline? |

| Andrada et al (2004)[35] | C | C | C | C | C |

| Bechtold et al (2006)[36] | C | C | N | NA | C |

| Harikumar et al (2006)[38] | C | C | C | C | P1 |

| Lee et al (2002)[41] | C | P | C | N | C |

| Ovayolu et al (2006)[42] | C | C | N | NA | C |

| Schiemann et al (2002)[44] | C | N | N | NA | P2 |

| Smolen et al (2002)[45] | C | N | N | NA | C |

| Uedo et al (2004)[46] | C | N | N | NA | C |

In 2005, colorectal cancer was the fourth most frequent cancer type worldwide for both sexes and colon cancer accounted for about 655 000 deaths per year[1]. Most colon cancers develop from polyps that grow abnormally in the colon. If polyps grow unnoticed and are not removed, they may become cancerous. Indeed, colorectal cancer is among the most preventable and curable cancers and with early detection 75%-90% of them can be prevented[2]. The aim of screening is to find precancerous polyps so they can be removed before they become cancerous. Screening for colon cancer has been shown to be effective in reducing mortality[3].

Colonoscopy is now the recommended method for screening colon cancer[4]. During a colonoscopy procedure, physicians insert a colonoscope into the rectum of a patient from the anus and slowly guide it into the colon for direct visualization and diagnosis[5]. As can be imagined, it is not a comfortable experience. In fact, many people refuse to undergo colonoscopy because of discomfort and anxiety[6], some feel out of control with what would be happening during the procedure and were fearful of looking foolish[7]. Even those who agree to undergo a colonoscopy feel frightened and anxious before the procedure[8]. After it, they express it was an unpleasant and stressful experience[9]. Therefore, most physicians prefer to perform colonoscopy with conscious sedation[10] although some still start the procedure without sedation, particularly in non-anxious patients[11].

Since the use of sedation is risky-it may contribute to the occurrence of cardiovascular events and is associated with the risk of cardio-respiratory complication[12,13] especially for elderly patients[14]-pand costly, non-pharmacological methods for alleviating patients’ discomfort and anxiety have been developed and music therapy is one of them. The use of music therapy to promote relaxation has a long history in medicine[15,16]. The ancient Chinese medical reference, Yellow Emperor’s Classics of Internal Medicine, mentioned the use of music for treatment[17], while ancient Indian treatises, like Samaveda, stated the therapeutic utility of music[18]. Earlier studies show the effectiveness of music on patients with acute myocardial infarctions[19] and receiving intensive medical/surgical care[20]. The effects of music on different screening procedures were examined during the early 1990s. For example, Fullhart[21] and Palakanis[6] studied anxiety in patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy and Bampton[22] assessed the role of relaxation music on patient tolerance of gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. Since then, more and more studies have examined the effect of music during colonoscopy, but no conclusion has yet been reached about its effectiveness. Recently, a meta-analysis[23] focusing on the general endoscopic procedure was published and the authors reported significantly lower anxiety levels and shorter procedure times. The aim of this meta-analysis is to integrate results from different studies in examining the effectiveness of music in reducing procedure time and amount of sedation used during colonoscopy.

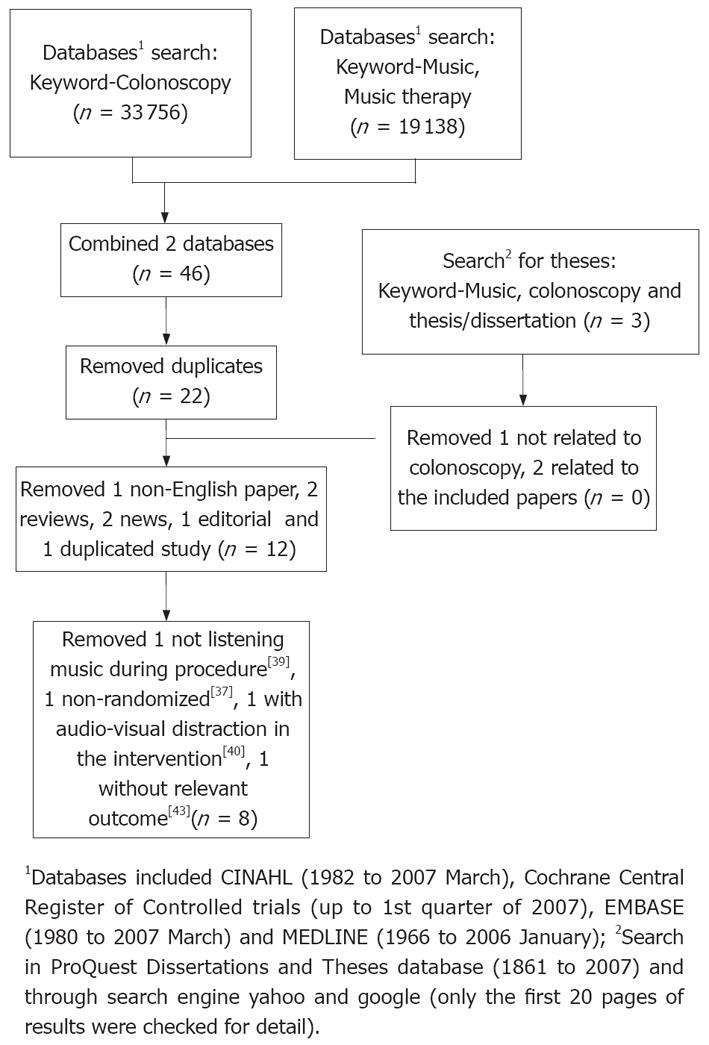

We identified studies to evaluate the effect of listening to music during colonoscopy. The electronic search was conducted on six databases, namely, AMED-Allied and Complementary Medicine (1985 to 2007), ACP journal club (1991 to 2007), CINAHL (1982 to March 2007), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (up to 1st quarter of 2007), EMBASE (1980 to March 2007), and MEDLINE (1966 to March 2007). Only two sets of keywords, i.e. Colonoscopy and Music/Music, were used to include as many articles as possible. We also attempted to identify any potential unpublished studies such as theses and dissertations using the above keywords through the ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database, and the web using Internet search engines, Google and Yahoo, with thesis or dissertation as additional keywords. Reference lists of the collected papers were also checked for any potential articles.

Only randomized controlled studies reported in English were included. At least one of the comparison groups included listening to music during colonoscopy as part of the intervention.

For each eligible study, we extracted information on author/s, year of publication, age distribution, gender proportion, other demographic data, intervention, outcome measures, and results. The data extraction form was modified from the data extraction form of van Tulder[24]. Two investigators (WT and EW) of the study independently extracted the data, which was then summarized by one of them. Agreement was reached on the extracted data before proceeding to data analysis.

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Jadad’s scale[25]. The quality variables recorded in the criteria list included the procedure of patient allocation, information regarding withdrawals and dropouts, blinding of patients, and outcome assessment. A maximum of five points can be obtained using the scale. However, as blinding of patients is difficult while assessing behavioral interventions[26], only blinding of outcome assessors was considered in the scale. Furthermore, as withdrawals and attrition of patients were unlikely in such a short period, such item in the Jadad’s scale was also ignored. Therefore, the maximum points obtainable for each study became four. Besides the Jadad’s scale, one additional question was extracted from van Tulder[24] for assessing the comparability of the two comparison groups.

Random-effect models were used to combine the outcome effect, i.e. the (standardized) difference between treated and control groups, for each study[27]. Heterogeneity was examined using the Q-test and I2[27]. All analyses were conducted using RevMan[27]. Publication bias was examined by funnel plot and Egger’s regression[28].

The electronic search was conducted in May 2007 and 19 records were found. The title and abstracts of these papers were examined and it was found that one was written in Portuguese[29], one was a systematic review focus on pain[30], one was a discussion paper on the use of sedation[31], one was an editorial[32], and two were news[33,34]. One paper[35] occurred twice in our search as the surname of the first author was recorded differently in two electronic databases (EBASE and MEDLINE), so one was removed. Hence, only 12 studies[35-46] were included and the full articles were obtained for further examination. A study[37] was found to be a non-randomized study and was excluded and another study[43] not examining the procedure time nor the amount of sedation was also excluded. One study[39] required their subjects in the intervention group to listen to music before the colonoscopy procedure on a voluntary basis. The author was contacted to see how many subjects in the intervention group listened to music during the procedure. Although the author implied that most of the subjects continued to listen to music during the procedure, the study was excluded because not all participants in the intervention group listened to music during the procedure. Another study[40] provided audiovisual distraction to patients instead on listening to music alone and the effect may have been enhanced; therefore, it was also excluded from the analysis.

As to the search of potential theses or dissertations, one doctoral dissertation[47] and two master theses[48,49] were identified and their abstracts were obtained. However, one[48] was not related to colonoscopy and the others[47,49] related to the papers from previous search[40,45]. A flowchart is provided to show the search history (Figure 1).

A total of 722 subjects were involved in 8 studies (Table 1), four from Europe[35,36,42,44], two from the US[36,45], and three from Asia[38,41,46]. Two studies[38,45] provided different types of music for their patients to choose from. Four studies broadcasted the music through headphones/earphones[35,38,41,45], three broadcasted as background music[36,42,44], and one did not specify the media method[46]. Seven studies mentioned that all colonoscopy procedures were conducted by an experienced colonoscopist[42,46] or a group of experienced colonoscopists[35,36,38,41] for both comparison groups.

All of the included studies were randomized controlled studies and only five of them reported the method of randomization[35,36,38,41,42]. No information on attrition was reported in any study probably because most of the procedures were completed in a relatively short period of time. Incomplete procedures were reported in two studies but no significant incomplete rates were detected[35,41]. Although it would be impossible to blind the subjects, outcomes assessor was blinded in two studies[35,38] by requesting the patients in the control group to take the earphones. Six studies[35,36,41,42,45,46] showed that baseline characteristics between control and treatment groups were comparable. One study did not provide the test statistics[44] and one did not report the baseline characteristics[38] (Table 2). Overall, five studies[35,36,38,41,42] got 2 points (half) or above in our modified Jadad’s scale.

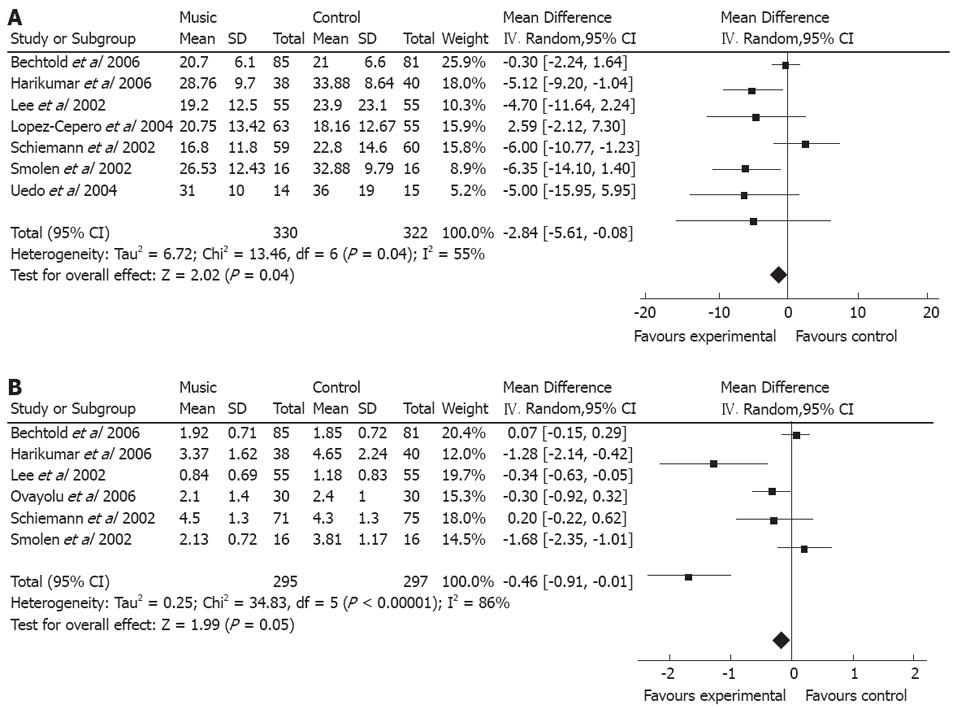

The total time taken for the procedure between music and control groups was measured in seven studies[35,36,38,41,44-46]. Six of them[36,38,41,44-46] showed a reduction of time in the music group but only in one case was this significant[44]. Since two studies[36,38] did not provide the means or standard deviations, the corresponding authors of the studies were contacted to obtain this information. Authors from both studies[36,38] generously provided the means and standard deviations of the respective parameters and therefore their results could be included in the analysis. The combined mean difference between the treated and control groups was -2.84 with 95% CI (-5.61 to -0.08). The Q-value and the I2 were 13.46 (P = 0.04) and 55%, suggesting possible heterogeneity among the studies. Publication bias was not detected using Egger’s regression method (P = 0.9133).

Six studies[36,38,41,42,44,45] examined the use of sedation, i.e. midazolam in mg, and four[38,41,42,45] showed a reduction in the music group. Sedation was given or added based on patients’ request[38,41,44] or colonoscopists’ decision[36,42]. The means and standard deviations of the 2 studies[36,38] were requested from the authors. The combined mean difference for the six trials was -0.46 with 95% CI (-0.91 to -0.01), showing a marginally significant reduction of the use of sedation in the music group. The Q-test and I2 were respectively 34.83 (P < 0.001) and 86% suggesting strong heterogeneity. Publication bias was not detected using Egger’s regression method (P = 0.1150).

Colon cancer is the fourth leading cause of death among all cancers[1] but remains one of the most preventable and curable cancers if detected early[2]. Screening for colon cancer has been shown to be an effective method of reducing the risk of mortality, but the compliance rate is still low probably due to the unpleasant feeling of patients during the procedure[9]. Non-pharmacological methods for alleviating patients discomfort and anxiety have been developed and, in the early 1990s, Palakanis[6] demonstrated that listening to music before and during sigmoidoscopy was effective in reducing one’s anxiety. Colonoscopy has been the recommended procedure for screening colon cancer[4] and more studies have been conducted in examining the effect of listening to music during this procedure.

Our results show that listening to music during the colonoscopy would effectively reduce the mean procedure time and the amount of sedation used. One possible explanation for the reduction of sedation is that patients in the music group are more relaxed and with less anxiety. Therefore, the physician can complete the procedure in a shorter period of time and use less sedation[45]. The reduction of procedure time implies a reduction of the anxious, frightening, and unpleasant time spent while undergoing the procedure and may be useful in enhancing the compliance rate.

It was reported that conscious sedation with midazolam contributed to the occurrence of cardiovascular events during colonoscopy[12] and was associated with the risk of cardio-respiratory complication[14]. Avoidance of sedation may provide a quicker patient discharge, less need for monitoring, and overall cost savings[50]. Our results also found a significant reduction in anxiety score, but only weak evidence was observed for pain score, blood pressure, and mean recovery time.

Besides the above-mentioned beneficial effects to patients, two advantages of listening to music during colonoscopy are cheapness and ease of implementation[51]. Although cassette players and compact disc players were used in most of the included studies, digital players, like MP3 players, may be a better choice in the future[52]. With advanced technology, a thumb-sized MP3 player can store hundreds of songs at a much lower cost. Therefore, more choices can be given to patients, which is important as personal preference has a strong impact on one’s responses to music[53].

No harmful effects from listening to music were reported in any study in the meta-analysis and other references that we read. Only one shortcoming about patients listening to music through headphone/earphone was the isolation of verbal communication between patients and the medical staff during the procedure. However, broadcasting the music as background music might disturb the staff conducting the procedure probably because an imposed choice of musical selection can be annoying to the listener[53].

Recently, a meta-analysis was published on a similar topic[23] but there are several differences between that study and the present one. First of all, colonoscopy was the focus of this paper. Second, this study’s search strategy was more comprehensive, meaning that more databases were included and theses/dissertations were also identified. Third, besides the numerically combined results, the characteristics of all included studies were presented and discussed in the text or in the table.

Although our findings confirm the effectiveness of listening to music during the colonoscopy procedure, several areas are worth further investigation. These include the choice of music, the mode of broadcasting music (earphone, background, or both), the possibility of using placebo to the patients in the control group, the possibility of blinding to the colonoscopist/s or medical staff involved in the procedure, the interaction of the medical staff to background music as well as the effect of playing audiovisual materials. Finally, it was suggested that the role of music should be considered whenever applicable[54].

Our results confirm that patient listening to music during colonoscopy is an effective way in reducing procedure time, anxiety, and the amount of sedation. More importantly, no harmful effects were observed for all the studies. Therefore, listening to music during colonoscopy should be recommended.

Colonoscopy is the recommended method for screening colon cancer but many people are unwilling to receive it because of fearing the pain, anxiety and other reasons. The use of music in medical research has long history and the beneficial effects of listening music during colonoscopy have been widely reported.

A meta-analysis was conducted to integrate results from different studies in examining the effectiveness of music in reducing the procedure time and the amount of sedation during colonoscopy.

Our results show that listening to music during colonoscopy may effectively reduce the mean procedure time and the amount of sedation used.

Listening to music during colonoscopy should be promoted because of its beneficial effect and negligible cost.

This is a research on a kind of a complementary and alternative medicine, a “music therapy”.

Peer reviewer: Yoshiharu Motoo, MD, PhD, FACP, FACG, Professor and Chairman, Department of Medical Oncology, Kanazawa Medical University,1-1 Daigaku, Uchinada, Ishikawa 920-0293, Japan

S- Editor Zhong XY L- Editor Negro F E- Editor Zhang WB

| 1. | WHO. Facts sheets, Cancer, WHO 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/index.html. |

| 2. | Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, Godlee F, Stolar MH, Mulrow CD, Woolf SH, Glick SN, Ganiats TG, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594-642. |

| 3. | Selby JV, Friedman GD, Quesenberry CP Jr, Weiss NS. A case-control study of screening sigmoidoscopy and mortality from colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:653-657. |

| 4. | Davila RE, Rajan E, Baron TH, Adler DG, Egan JV, Faigel DO, Gan SI, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, Lichtenstein D. ASGE guideline: colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:546-557. |

| 5. | Waye JD, Rex DK, Williams CB. Colonoscopy: Principles and practice. 1st ed. Malden, Mass. Oxford: Blackwell Sci Pub 2003; 655. |

| 6. | Palakanis KC, DeNobile JW, Sweeney WB, Blankenship CL. Effect of music therapy on state anxiety in patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:478-481. |

| 7. | Salmon P, Shah R, Berg S, Williams C. Evaluating customer satisfaction with colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 1994;26:342-346. |

| 8. | Salmore RG, Nelson JP. The effect of preprocedure teaching, relaxation instruction, and music on anxiety as measured by blood pressures in an outpatient gastrointestinal endoscopy laboratory. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2000;23:102-110. |

| 9. | Kim LS, Koch J, Yee J, Halvorsen R, Cello JP, Rockey DC. Comparison of patients' experiences during imaging tests of the colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:67-74. |

| 10. | Balsells F, Wyllie R, Kay M, Steffen R. Use of conscious sedation for lower and upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examinations in children, adolescents, and young adults: a twelve-year review. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:375-380. |

| 11. | Fisher NC, Bailey S, Gibson JA. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of sedation vs. no sedation in outpatient diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 1998;30:21-24. |

| 12. | Ristikankare M, Julkunen R, Laitinen T, Wang SX, Heikkinen M, Janatuinen E, Hartikainen J. Effect of conscious sedation on cardiac autonomic regulation during colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:990-996. |

| 14. | Yuno K, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Hifumi K, Omori M. Intravenous midazolam as a sedative for colonoscopy: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:981-984. |

| 15. | Rorke MA. Music therapy in the age of enlightenment. J Music Ther. 2001;38:66-73. |

| 16. | West M. Music Therapy in Antiquity. Horden P, editor. Music as medicine: the history of music therapy since antiquity. Aldershot; Brookfield, Vt: Ashgate 2000; 51-68. |

| 17. | Ni MS. The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of internal medicine: A new translation of the Neijing Suwen with commentary. Boston: Shambhala Pub 1995; 14-17. |

| 18. | Katz JB. Music Therapy: Some Possibilities in the Indian Tradition. Horden P, editor. Music as medicine: the history of music therapy since antiquity. Aldershot; Brookfield, Vt: Ashgate 2000; 84-102. |

| 19. | White JM. Music therapy: an intervention to reduce anxiety in the myocardial infarction patient. Clin Nurse Spec. 1992;6:58-63. |

| 20. | Updike P. Music therapy results for ICU patients. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1990;9:39-45. |

| 21. | Fullhart JW. Preparatory information and anxiety before sigmoidoscopy: a comparative study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 1992;14:286-290. |

| 22. | Bampton P, Draper B. Effect of relaxation music on patient tolerance of gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:343-345. |

| 23. | Rudin D, Kiss A, Wetz RV, Sottile VM. Music in the endoscopy suite: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Endoscopy. 2007;39:507-510. |

| 24. | van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine. 2003;28:1290-1299. |

| 25. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. |

| 26. | Monninkhof E, van der Valk P, van der Palen J, van Herwaarden C, Partridge MR, Zielhuis G. Self-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Thorax. 2003;58:394-398. |

| 27. | Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program] Version 5. 0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration 2008; . |

| 28. | Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. |

| 29. | Arruda Alves PR, Roncaratti E, Habr Gama A. Reduction in salivary levels of cortisol by music therapy during colonoscopy. GED-Gastrenterologia Endoscopia Digestiva. 2004;23:83-84. |

| 30. | Cepeda MS, Carr DB, Lau J, Alvarez H. Music for pain relief. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;23:CD004843. |

| 31. | Lazzaroni M, Bianchi Porro G. Preparation, premedication, and surveillance. Endoscopy. 2005;37:101-109. |

| 32. | Lotufo PA. The noise stops you from hearing good music: the possibilities for a mortality reduction program for cancer of the colon and rectum in Sao Paulo. Sao Paulo Med J. 2003;121:95-96. |

| 33. | Kurth T, Krevvsky B, Chiu C. Late-breaking news. Bottom Line Health. 2007;21:1. |

| 34. | Kurth T; Anonymous. Tuned up for colon test. Nur Standard. 2006;21:8. |

| 35. | Lopez-Cepero Andrada JM, Amaya Vidal A, Castro Aguilar-Tablada T, Garcia Reina I, Silva L, Ruiz Guinaldo A, Larrauri De la Rosa J, Herrero Cibaja I, Ferre Alamo A, Benitez Roldan A. Anxiety during the performance of colonoscopies: modification using music therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1381-1386. |

| 36. | Bechtold ML, Perez RA, Puli SR, Marshall JB. Effect of music on patients undergoing outpatient colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7309-7312. |

| 37. | Binek J, Sagmeister M, Borovicka J, Knierim M, Magdeburg B, Meyenberger C. Perception of gastrointestinal endoscopy by patients and examiners with and without background music. Digestion. 2003;68:5-8. |

| 38. | Harikumar R, Raj M, Paul A, Harish K, Kumar SK, Sandesh K, Asharaf S, Thomas V. Listening to music decreases need for sedative medication during colonoscopy: a randomized, controlled trial. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;25:3-5. |

| 39. | Hayes A, Buffum M, Lanier E, Rodahl E, Sasso C. A music intervention to reduce anxiety prior to gastrointestinal procedures. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2003;26:145-149. |

| 40. | Lee DW, Chan AC, Wong SK, Fung TM, Li AC, Chan SK, Mui LM, Ng EK, Chung SC. Can visual distraction decrease the dose of patient-controlled sedation required during colonoscopy? A prospective randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2004;36:197-201. |

| 41. | Lee DW, Chan KW, Poon CM, Ko CW, Chan KH, Sin KS, Sze TS, Chan AC. Relaxation music decreases the dose of patient-controlled sedation during colonoscopy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:33-36. |

| 42. | Ovayolu N, Ucan O, Pehlivan S, Pehlivan Y, Buyukhatipoglu H, Savas MC, Gulsen MT. Listening to Turkish classical music decreases patients' anxiety, pain, dissatisfaction and the dose of sedative and analgesic drugs during colonoscopy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7532-7536. |

| 43. | Salmore RG, Nelson JP. The effect of preprocedure teaching, relaxation instruction, and music on anxiety as measured by blood pressures in an outpatient gastrointestinal endoscopy laboratory. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2000;23:102-110. |

| 44. | Schiemann U, Gross M, Reuter R, Kellner H. Improved procedure of colonoscopy under accompanying music therapy. Eur J Med Res. 2002;7:131-134. |

| 45. | Smolen D, Topp R, Singer L. The effect of self-selected music during colonoscopy on anxiety, heart rate, and blood pressure. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15:126-136. |

| 46. | Uedo N, Ishikawa H, Morimoto K, Ishihara R, Narahara H, Akedo I, Ioka T, Kaji I, Fukuda S. Reduction in salivary cortisol level by music therapy during colonoscopic examination. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:451-453. |

| 47. | Lee DWH. The use of patient-controlled and adjunct sedation for colonoscopy. Thesis. Chinese University of Hong Kong. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration 2005; . |

| 48. | Parker DB. The effect of Music Therapy for pain and anxiety versus literature on the immediate and future perceptions of cardiac patients. Thesis. The Florida State University. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration 2004; . |

| 49. | Smolen D, Topp R, Singer L. The effect of self-selected music during colonoscopy on anxiety, heart rate, and blood pressure. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15:126-136. |

| 50. | Takahashi Y, Tanaka H, Kinjo M, Sakumoto K. Sedation-free colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:855-859. |

| 51. | Kemper KJ, Danhauer SC. Music as therapy. South Med J. 2005;98:282-288. |

| 52. | Maag M. Podcasting and MP3 players: emerging education technologies. Comput Inform Nurs. 2006;24:9-13. |

| 53. | Bonny HL. Music and healing. Music Ther. 1986;6A:3-12. |

| 54. | Thaut MH. The future of music in therapy and medicine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1060:303-308. |