Published online Aug 28, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5084

Revised: August 11, 2008

Accepted: August 18, 2008

Published online: August 28, 2008

AIM: To evaluate the clinical outcome of Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus.

METHODS: From January 1998 to December 2001, 73 patients with lower thoracic esophageal carcinoma underwent Ivor-Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy. Clinicopathological information, postoperative complications, mortality and long term survival of all these patients were analyzed retrospectively.

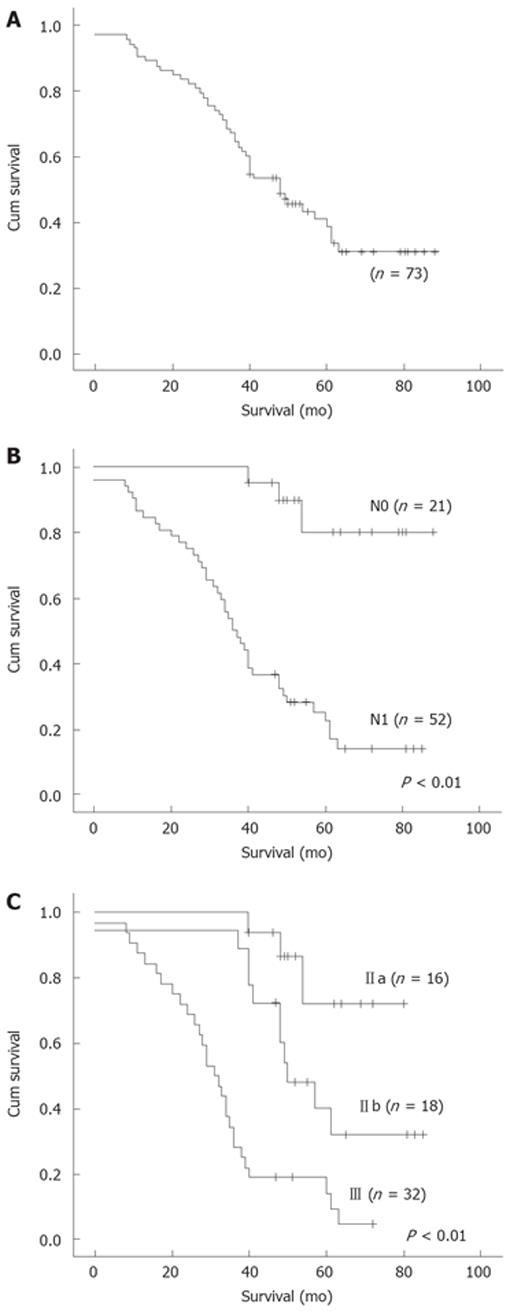

RESULTS: The operative morbidity and mortality was 15.1% and the mortality was 2.7%. Lymph node metastases were found in 52 patients (71.2%). Nodal metastases to the upper, middle, lower mediastini and upper abdomen were found in 13 (17.8%), 15 (20.5%), 30 (41.1%), and 25 (34.2%) patients, respectively. Postoperative staging was as follows: stageI in 5 patients, stage II in 34 patients, stage III in 32 patients, and stage IV in 2 patients, respectively. The overall 5-year survival rate was 23.3%. For N0 and N1 patients, the 5-year survival rate was 38.1% and 17.3%, respectively (χ2 = 22.65, P < 0.01). The 5-year survival rate for patients in stages IIa, IIb and III was 31.2%, 27.8% and 12.5%, respectively (χ2 = 29.18, P < 0.01).

CONCLUSION: Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field (total mediastinum) lymphadenectomy is a safe and appropriate operation for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus.

- Citation: Wu J, Chai Y, Zhou XM, Chen QX, Yan FL. Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(32): 5084-5089

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i32/5084.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.5084

| Stage | TNM | Patients, n (%) |

| I(n = 5) | T1N0M0 | 5 (6.8) |

| IIa (n = 16) | T2N0M0 | 7 (9.6) |

| T3N0M0 | 9 (12.3) | |

| IIb (n = 19) | T1N1M0 | 3 (4.1) |

| T2N1M0 | 15 (20.5) | |

| III (n = 32) | T3N1M0 | 29 (39.7) |

| T4N1M0 | 3 (4.1) | |

| IV (n = 2) | T3N1M1 | 2 (2.7) |

| Complications | Patients | Patients died |

| Pneumonia | 4 (5.5) | 1 (1.4) |

| Vocal cord palsy | 3 (4.1) | 0 (0) |

| Arrhythmia | 3 (4.1) | 0 (0) |

| Anastomotic leakage | 2 (2.7) | 1 (1.4) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| Wound infection | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

| T | N0 | N1 | Prevalence of nodal metastases (%) |

| T1 (n = 8) | 5 | 3 | 37.5 |

| T2 (n = 22) | 7 | 15 | 68.2 |

| T3 (n = 40) | 9 | 31 | 77.5 |

| T4 (n = 3) | 0 | 3 | 100 |

| Metastatic location | Patients with negative lymph node (n) | Patients with positive lymph node (n) | Frequency of nodal metastases (%) |

| Upper mediastinum | 60 | 13 | 17.8 |

| Middle mediastinum | 58 | 15 | 20.5 |

| Lower mediastinum | 43 | 30 | 41.1 |

| Upper abdomen | 48 | 25 | 34.2 |

Radical esophagectomy with lymphadenectomy remains the mainstay of curative therapy for esophageal carcinoma. Complete resection of esophagus and regional lymph node (R0 resection) are essential to improve long-term survival[1-3]. For carcinomas of the lower thoracic esophagus, different tumor characteristics between the Western and Eastern countries cause various attitudes on their surgical management[4]. Depending on the attending surgeon’s philosophy, surgical approaches to carcinomas of the lower thoracic esophagus vary from the conventional left thoraco-abdominal approach[5,6] to the transhiatal approach without thoracotomy[7-9], Ivor Lewis approach[10-12], and recently reported thoracoscopic approach[13-15]. On the other hand, controversy continues over the optimal extent of lymphadenectomy to be performed with esophagectomy. Some authors do not favor lymphadenectomy considering lymph node involvement as systemic disease with no hope for cure, and the primary goal of surgical intervention is palliative, with a low surgical morbidity and mortality[8]. However, some authors prefer two-field lymphadenectomy and regard it as a standard surgical procedure[10,12,16]. What is more, other authors, mainly from Japan, advocate three-field lymphadenectomy in order to obtain accurate staging, control locoregional recurrence and improve long-term survival[17-20].

At our hospital, the main surgical approach to lower thoracic esophageal carcinoma is the Ivor Lewis approach, instead of left thoraco-abdominal approach that is widely adopted in China, because Ivor Lewis approach provides a wider extent of lymphadenectomy than left thoraco-abdominal approach, and the chance of obtaining R0 resection is greater. The aim of this study was to retrospectively assess our results of Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus.

From January 1998 to December 2001, 73 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus underwent Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field lymph node dissection at Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, Hangzhou, China. There were 65 men and 8 women. Median age was 57 years (range, 39 to 78 years). Preoperative evaluation was performed for all patients with a barium swallow examination, endoscopy with biopsy, ultrasonography of the neck and upper abdominal compartment. Cardiac and pulmonary functions were also routinely performed for these patients to determine their ability to withstand the planned surgical procedure. Before treatment, diagnosis of all patients was established histologically. No patient received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before operation. Postoperative staging was based on the 2002 UICC-TNM classification[21].

Duration of surgery, operative blood loss, and the number of lymph nodes were recorded. Postoperative complications were also recorded. Operative mortality was defined as any death during the first 30 d after operation or during the same hospital stay.

All patients underwent Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy. In brief, all resections were carried out by initial abdominal exploration through an upper midline laparotomy. The stomach was mobilized on the right gastric and gastroepiploic arteries. The left gastric artery was divided at its origin, and all lymph nodes along the celiac axis and its three branches along the left aspect of the portal vein, in front of the inferior vena cava, along the diaphragmatic pillars, and in front of the left adrenal gland were en bloc resected. A pyloromyotomy was performed routinely for all the patients. No drainage procedure was done. After the abdominal stage, a right posterolateral thoracotomy was performed. The thoracic dissection included removal of azygous arch with its associated lymph nodes, thoracic duct, and the low paratracheal, subcarinal, paraesophageal, and parahiatal nodes in continuity with the resected esophagus. In addition, upper mediastinal, paratracheal lymphatic tissue including lymph nodes of the left and right recurrent laryngeal nerves were also removed. Denudation of the lesser curvature was usually performed in the pleural cavity. After resection of the specimen, an anastomosis was constructed between the stomach and esophagus. The anastomosis was located in the apex of the chest in all patients.

After surgery, all patients returned to the intensive care unit for 2 d on average. On day 5 after surgery, patients underwent contrast X-ray study for assessment of esophagogastric anastomosis and then received enteral feeding.

Postoperative data were collected at the outpatient clinic. Follow-up data were obtained by telephone. The follow-up time ranged 0-88 mo (median 47 mo). Survival time was defined as the period from the date of surgery until death or the most recent follow-up investigation (September 2005), with none lost to follow-up.

Survival analysis was carried out with the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used for comparisons. Estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CI95) were given for 5 years. Fisher’s exact two-tailed test was used to compare categorical data. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All the 73 patients acquired complete resection (R0 resection). The postoperative stage and TNM classification are shown in Table 1. Of the 8 patients with pathological T1 tumors, 2 had muscularis mucosae tumors and 6 had submucosal tumors. Nodal involvement was found in 3 of the 6 patients with submucosal tumors. Of the 3 patients with pathological T4 tumors, 2 had liver involvement and 1 had lung involvement. Combined resections were performed for the 3 patients. Metastases were found in celiac nodes of 2 patients with M1 disease.

The operation time was 243 ± 40 min. The operative blood loss was 365 ± 230 mL. The number of lymph nodes resected was 31 ± 11 (median, 27). Postoperative complications are listed in Table 2. Complications occurred in 11 patients (15.1%, CI95 6.9%-23.3%). Of the 73 patients, 2 (2.7%, CI95 0%-6.5%) died due to pneumonia and anastomotic leakage, respectively, within 30 d of the operation.

Lymph node metastases were found in 52 patients and the prevalence of nodal metastasis was 71.2% (CI95 60.8%-81.6%). As shown in Table 3, the prevalence of nodal metastases increased with increasing tumor depth, but the difference was not statistically significant. The prevalence of nodal metastases was 37.5% in T1 stage patients, 77.5% in T3 stage patients, which was statistically significant (χ2 = 5.06, P = 0.025). Other differences in the two stages were not statistically significant (T1 vs T2, T1 vs T4, T2 vs T3, T2 vs T4, T3 vs T4).

The frequencies of nodal metastases in different anatomical regions are shown in Table 4, which were statistically significant (P = 0.004). The frequency in lower mediastinum (41.1%) was higher than that in upper (17.8%, χ2 = 9.53, P = 0.007), and middle mediastini (20.5%, χ2 = 7.23, P = 0.007). The frequency in upper abdomen (34.2%) was higher than that in upper mediastinum (17.8%) (χ2 = 5.12, P = 0.024). Other differences in frequencies between the two regions were not statistically significant. Among the 52 patients with lymph node involvement, 13 (25.0%, CI95 13.3%-36.7%) had skip nodal metastases without invasion of peritumoral nodes. Isolated lymph node involvement was observed in the upper mediastinum of 6 patients (4 with positive left recurrent laryngeal nerve nodes, 2 positive right left laryngeal nerve nodes) and in the upper abdomen of 7 patients with positive left gastric arterial nodes, respectively. These patients (17.8%, CI95 9.0%-26.6%) did not undergo two-field lymphadenectomy but received incomplete resections (R1 resection of microscopically residual tumors or R2 resection of macroscopically residual tumors). Had upper mediastinal lymphadenectomy not been performed, six patients (8.2%, CI95 1.9%-15.5%) would not have undergone upper mediastinal lymphadenectomy but received inaccurate staging.

The 5-year survival rate was 23.3% (CI95 13.5%-32.9%) for all patients (Figure 1A). The 5-year survival rate was 38.1% (CI95 17.4%-58.8%) and 17.3% (CI95 7.0%-27.6%) for N0 and N1 patients, respectively (χ2 = 22.65, P < 0.01, Figure 1B). The 5-year survival rate for patients in stages IIa, IIb, and III was 31.2% (CI95 8.9%-53.5%), 27.8% (CI95 7.1%-48.5%) and 12.5% (CI95 1.0%-24.0%), respectively (χ2 = 29.18, P < 0.01, Figure 1C).

Studies demonstrated that extensive submucosal lymphatic drainage to the esophageal wall causes a unique pattern of nodal metastases[1,2,4]. It was reported that the prevalence of nodal metastases of lower thoracic esophageal carcinoma is up to 70%[1-3]. Lymphatic dissemination is an early event of esophageal carcinoma, and involved nodes are found in 30%-40% of submucosal tumors[2,3]. These data are consistent with our results (71.2% and 50%, respectively). It has been documented that the likelihood of nodal metastases of esophageal carcinoma depends on the depth of tumor invasion of the esophageal wall[2,3]. The prevalence of nodal metastases increased with the increasing tumor invasion depth in this study. The prevalence of nodal metastases had no difference between the two groups according to their T status, suggesting that it may be related to the small sample size. Unlike squamous cell carcinoma of the upper thoracic esophagus, which shows lymphatic flow is mainly in the upward direction along the esophageal wall, squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus, which shows lymphatic spread is mainly in the downward direction along the esophageal wall[2,4], which is consistent with our findings. Although to some degree, the frequencies of lower mediastinal and upper abdominal metastases were higher than those of upper and middle mediastinal metastases, the frequency of upper mediastinal metastases (17.8%) was still not as low as that of middle mediastinal metastases (20.5%) in the patients with lower thoracic esophageal carcinoma. An even higher frequency of upper and/or middle mediastinal metastases (30%-40%) has been reported[2,4]. In our study, skip nodal metastases were found in 25% of nodal positive patients. Of the 52 patients, 6 (11.5%) and 7 (13.5%) had positive nodes in the upper mediastinum and abdomen, respectively. Hosch et al[22] reported that skip metastases nodal positive patients and a frequent event in esophageal cancer. Based on these nodal metastatic features, in order to obtain R0 resection, lymphadenectomy with upper mediastinal dissection should be performed for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower esophagus.

The greater the number of lymph nodes is removed, the greater the chance of obtaining a R0 resection, and the more precisely the disease can be staged[1-3,11]. The extent of lymphadenectomy for a cancer in the thoracic esophagus has been classified by the Consensus Conference of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus (ISDE) as a standard, extended, total, or three-field lymphadenectomy[23]. The optimal lymphadenectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus is still debatable. Of the 4 types of lymphadenectomy, three-field lymphadenectomy can, most likely, achieve a R0 resection and accurate staging. The question is whether it definitely improves the long-term survival of patients. However, most data are available from nonrandomized retrospective historical studies in Japan. Igaki et al[4] reported that three-field lymphadenectomy could prolong the survival time of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus compared to 2-field lymphadenectomy for nodal metastases present in the upper and/or middle mediastinum. Fujita et al[24] reported that there is no difference in survival rate for patients with lower thoracic esophageal cancer between the two procedures of lymphadenectomy. Three-field lymphadenectomy has its obvious advantages and disadvantages[16,18]. Hence, two field lymphadenectomy seems to be a more reasonable choice of treatment for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus. This viewpoint is far out weighed by the fact that the emphasis on three-field lymphadenectomy has shifted to lymphadenectomy along the recurrent laryngeal nerve chains, where lymph nodes could be dissected through two-field lymphadenectomy[16]. Among the other three types of lymphadenectomy, total (mediastinal) lymphadenectomy which was applied in this study, provides more chances to obtain a R0 resection and accurate staging than the other two types of lymphadenectomy. As our data show, if a standard lymphadenectomy was performed, positive nodes would be left intact, thus only R1 or R2 resection could be achieved, leading to stage migration from N0 to N1 in 6 patients (8.2%). If an extended lymphadenectomy was performed, stage migration from N0 to N1 would occur in 4 patients (5.5%), which can be explained by the fact that the extent of standard lymphadenectomy does not cover the upper and left upper mediastini. Total (mediastinal) lymphadenectomy is therefore an alternative for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus. Then, which surgical approach could satisfy the demand for total lymphadenctomy? Transhiatal approach without thoracotomy is unlikely to be chosen. In the left thoraco-abdominal approach we used previously, upper mediastinal lymph nodes are not available. In the McKeown approach (anterolateral right thoracotomy), a radical lymphadenectomy is more difficult to achieve than the Ivor Lewis approach[5,12]. Thoracoscopic approach to esophageal carcinoma remains to be investigated and no systemic data are available to support its advantages over the minimally invasive approach to esophagectomy[25]. Ivor Lewis approach which allows complete visualization of mediastinum, especially upper mediastinum, seems to be most appropriate for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus.

Morbidity increases with the extent of lymphadene-ctomy but does not lead to a higher mortality[11]. Pneumonia was the most common complication in this study, which is consistent with previous reports[10-12]. Vocal cord palsy caused by lymphadenectomy around recurrent laryngeal nerves also occurs occasionally. Functional mediastinal lymphadenectomy can preserve the bronchial artery and bronchial branches of the vagus nerve, thus reducing the respiratory complications[20,26]. To prevent vocal cord palsy, electrocautery close to the recurrent laryngeal nerve and drawing the nerve with a vessel tape should be avoided during lymphadene-ctomy[19].

The overall 5-year survival rate of our patients was only 23.3%, which may be due to the small sample size in our study. On the other hand, the survival of patients was ascertained in September 2005 when 15 patients were alive at the most recent follow-up. Accordingly, this overall survival rate could not completely explain the effect of treatment since we did not make comparisons with others. However, there was a significant difference in the survival rate between the two groups of patients with different N status and different stages. This series were proved to be more homogenous with regard to the clinical variables, such as tumor site and pathological type. The surgical procedure performed in this series revealed more R0 resection and staging information than other surgical procedures (except three-field lymphadenectomy). Compared to other surgical procedures, Ivor Lewis esophagectomy with two-field (total mediastinal) lymphadenectomy could achieve better results in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus. Because of the small sample size used in this study, further studies are needed to confirm our results.

In conclusion, Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field (total mediastinal) lymphadenectomy is a safe and appropriate surgical procedure for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower esophagus.

Radical esophagectomy with lymphadenectomy is still the mainstay of curative therapy for esophageal carcinoma. This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical outcome of Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with two-field lymphadenctomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus.

Adenocarcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus is a common pathological type in Western countries, while squamous cell carcinoma is the main type in Eastern countries. The attitudes to the surgical approach and the extent of the lymphadenectomy for the lower thoracic esophageal carcinoma are different in Western and Eastern countries. Western general thoracic surgeons prefer the transhiatal approach and limited extent of lymphadenectomy, whereas Eastern general thoracic surgeons prefer the transthoracic approach and 2-field or 3-field lymphadenectomy.

In China, the left thoracoabdominal approach and standard 2-field lymphadenectomy are widely performed for lower thoracic esophageal carcinoma. In our clinical practice, however, they are widely performed as upper mediastinal lymphadenectomy. Furthermore, the prevalence of upper mediastinal nodal involvement is not low. 3-field lymphadenectomy is still controversial. This type of lymphadenectomy is not routinely performed in our institution. We prefer the Ivor Lewis approach with total mediastinal 2-field lymphadenectomy in the treatment of this disease.

Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy with 2-field lymphadenectomy is a safe surgical procedure for squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus.

Ivor Lewis subtotal esophagectomy is a laparotomy followed by a right thoracotomy. Two-field total mediastinal lymphadenectomy involves resection of bilateral upper mediastinum in addition to a standard lymphadenectomy.

The paper is scientific, innovative and readable, showing the advanced level of clinical research in gastroenterology both at home and abroad.

Peer reviewer: Dusan M Jovanovic, Professor, Institute of Oncology, Institutski Put 4, Sremska Kamenica 21204, Serbia

S- Editor Li DL L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Lerut T, Coosemans W, Decker G, De Leyn P, Moons J, Nafteux P, Van Raemdonck D. Extended surgery for cancer of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. J Surg Res. 2004;117:58-63. |

| 2. | Akiyama H, Tsurumaru M, Udagawa H, Kajiyama Y. Radical lymph node dissection for cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg. 1994;220:364-372; discussion 372-373. |

| 3. | Collard JM, Otte JB, Fiasse R, Laterre PF, De Kock M, Longueville J, Glineur D, Romagnoli R, Reynaert M, Kestens PJ. Skeletonizing en bloc esophagectomy for cancer. Ann Surg. 2001;234:25-32. |

| 4. | Igaki H, Tachimori Y, Kato H. Improved survival for patients with upper and/or middle mediastinal lymph node metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus treated with 3-field dissection. Ann Surg. 2004;239:483-490. |

| 5. | Lerut T, Coosemans W, Decker G, De Leyn P, Moons J, Nafteux P, Van Raemdonck D. Surgical techniques. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92:218-229. |

| 6. | Forshaw MJ, Gossage JA, Ockrim J, Atkinson SW, Mason RC. Left thoracoabdominal esophagogastrectomy: still a valid operation for carcinoma of the distal esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19:340-345. |

| 7. | Hulscher JB, van Sandick JW, de Boer AG, Wijnhoven BP, Tijssen JG, Fockens P, Stalmeier PF, ten Kate FJ, van Dekken H, Obertop H. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1662-1669. |

| 8. | Orringer MB. Transhiatal esophagectomy without thoracotomy for carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg. 1984;200:282-288. |

| 9. | Sanders G, Borie F, Husson E, Blanc PM, Di Mauro G, Claus C, Millat B. Minimally invasive transhiatal esophagectomy: lessons learned. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1190-1193. |

| 10. | Stilidi I, Davydov M, Bokhyan V, Suleymanov E. Subtotal esophagectomy with extended 2-field lymph node dissection for thoracic esophageal cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;23:415-420. |

| 11. | D’Journo XB, Doddoli C, Michelet P, Loundou A, Trousse D, Giudicelli R, Fuentes PA, Thomas PA. Transthoracic esophagectomy for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus: standard versus extended two-field mediastinal lympha-denectomy? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27:697-704. |

| 12. | Visbal AL, Allen MS, Miller DL, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, Pairolero PC. Ivor Lewis esophagogastrectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1803-1808. |

| 13. | Taguchi S, Osugi H, Higashino M, Tokuhara T, Takada N, Takemura M, Lee S, Kinoshita H. Comparison of three-field esophagectomy for esophageal cancer incorporating open or thoracoscopic thoracotomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1445-1450. |

| 14. | Nguyen TN, Hinojosa M, Fayad C, Gray J, Murrell Z, Stamos M. Laparoscopic and thoracoscopic Ivor Lewis esophagectomy with colonic interposition. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:2120-2124. |

| 15. | Smithers BM, Gotley DC, Martin I, Thomas JM. Comparison of the outcomes between open and minimally invasive esophagectomy. Ann Surg. 2007;245:232-240. |

| 16. | Law S, Wong J. Two-field dissection is enough for esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2001;14:98-103. |

| 17. | Altorki N. En-bloc esophagectomy--the three-field dissection. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:611-619, xi. |

| 18. | Fang W, Kato H, Tachimori Y, Igaki H, Sato H, Daiko H. Analysis of pulmonary complications after three-field lymph node dissection for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:903-908. |

| 19. | Tachibana M, Kinugasa S, Yoshimura H, Shibakita M, Tonomoto Y, Dhar DK, Nagasue N. Clinical outcomes of extended esophagectomy with three-field lymph node dissection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2005;189:98-109. |

| 20. | Kakegawa T. Forty years’ experience in surgical treatment for esophageal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2003;8:277-288. |

| 21. | International union against cancer. In: Sobin LH, Wittekind CH, editors. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 6th ed. New York: Wiley-Liss 2002; . |

| 22. | Hosch SB, Stoecklein NH, Pichlmeier U, Rehders A, Scheunemann P, Niendorf A, Knoefel WT, Izbicki JR. Esophageal cancer: the mode of lymphatic tumor cell spread and its prognostic significance. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1970-1975. |

| 23. | Bumm R, Wong J. More or less surgery for esophageal cancer: extent of lymphadenectomy for squamous cell esophageal carcinoma: How much is necessary? Dis Esophagus. 1994;7:151-155. |

| 24. | Fujita H, Sueyoshi S, Tanaka T, Fujii T, Toh U, Mine T, Sasahara H, Sudo T, Matono S, Yamana H. Optimal lymphadenectomy for squamous cell carcinoma in the thoracic esophagus: comparing the short- and long-term outcome among the four types of lymphadenectomy. World J Surg. 2003;27:571-579. |

| 25. | Wu PC, Posner MC. The role of surgery in the management of oesophageal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:481-488. |

| 26. | Pramesh CS, Mistry RC, Sharma S, Pantvaidya GH, Raina S. Bronchial artery preservation during transthoracic esophagectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2004;85:202-203. |