Published online Aug 28, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5073

Revised: July 14, 2008

Accepted: July 21, 2008

Published online: August 28, 2008

AIM: To investigate the feasibility of treatment for upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage with personal stage nutrition support.

METHODS: Forty-three patients with upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage were randomly divided into two groups. Patients in group A were treated with personal stage nutrition support and patients in group B were treated with total parental nutrition (TPN) in combination with operation. Nutritional states of the candidates were evaluated by detecting albumin (Alb) and pre-Alb. The balance between nutrition and hepatic function was evaluated by measurement of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin (Tbill) before and after operation. At the same time their complications and hospitalized time were surveyed.

RESULTS: Personal stage nutrition support improved upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage. The nutrition state and hepatic function were better in patients who received personal stage nutrition support than in those who did not receive TPN. There was no significant difference in the complication and hospitalized time in the two groups of patients.

CONCLUSION: Upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage can be treated with personal stage nutrition support which is more beneficial for the post-operation recovery and more economic than surgical operation.

- Citation: Wang Q, Liu ZS, Qian Q, Sun Q, Pan DY, He YM. Treatment of upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage with personal stage nutrition support. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(32): 5073-5077

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i32/5073.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.5073

| Time | Alb (g/L) | TSF (g/L) | Pre-Alb (mg/L) | ||||||

| A | B | P | A | B | P | A | B | P | |

| 1 d before treatment | 40 ± 2.1 | 39 ± 3.2 | 0.11 | 3.51 ± 0.17 | 3.49 ± 0.14 | 0.78 | 340 ± 51 | 341 ± 28 | 0.64 |

| 1 d after treatment | 39 ± 3.6 | 37 ± 2.5 | 0.06 | 3.27 ± 0.26 | 3.18 ± 0.21 | 0.26 | 327 ± 43 | 308 ± 19 | 0.15 |

| 15 d after treatment | 37 ± 2.7 | 35 ± 3.5 | 0.05 | 3.20 ± 0.33 | 2.98 ± 0.25 | 0.45 | 321 ± 37 | 271 ± 21 | 0.001 |

| 30 d after treatment | 38 ± 3.8 | 33 ± 3.2 | 0.001 | 3.28 ± 0.35 | 2.77 ± 0.22 | 0.001 | 325 ± 24 | 236 ± 17 | 0.001 |

| Time | Nitrogen balance (g) | ||

| A | B | P | |

| 1 d before treatment | -10 ± 3.6 | -8 ± 4.1 | 0.17 |

| 1 d after treatment | -11 ± 2.1 | -9 ± 4.5 | 0.81 |

| 15 d after treatment | 2 ± 2.9 | 2 ± 3.1 | 0.95 |

| 30 d after treatment | 6 ± 4.2 | 5 ± 4.8 | 0.51 |

| Time | AST (U/L) | ALT (U/L) | T bill (mol/L) | ||||||

| A | B | P | A | B | P | A | B | P | |

| 1 d before treatment | 26 ± 2.2 | 27 ± 1.9 | 0.27 | 27 ± 1.9 | 26 ± 1.6 | 0.85 | 15 ± 1.6 | 14 ± 1.8 | 0.68 |

| 1 d after treatment | 28 ± 2.4 | 29 ± 2.6 | 0.31 | 29 ± 2.3 | 30 ± 2.4 | 0.24 | 18 ± 2.1 | 19 ± 2.4 | 0.14 |

| 15 d after treatment | 42 ± 3.5 | 44 ± 3.1 | 0.07 | 52 ± 1.8 | 60 ± 1.5 | 0.001 | 30 ± 1.4 | 32 ± 2.6 | 0.004 |

| 30 d after treatment | 35 ± 3.3 | 63 ± 3.6 | 0.001 | 36 ± 2.7 | 65 ± 2.3 | 0.001 | 26 ± 3.7 | 48 ± 3.1 | 0.001 |

| A (n = 20) | B (n = 20) | P | |

| Stoma fistula | 0 | 2 | |

| Infection of incisional wound | 0 | 3 | |

| Abdominal distension | 2 | 0 | |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | 0 | |

| Infection of abdominal cavity | 1 | 1 | |

| Total incidence rate (%) | 20%(4/20) | 30%(6/20) | 0.53 |

| Average stay (d) | 40 ± 2.6 | 50 ± 3.7 | 0.001 |

| Average expenditure(10 thousand yuan) | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 0.001 |

The primary causes of death secondary to gastrointestinal fistulae and leakage include malnutrition, electrolyte imbalance, and sepsis. Without help of an experienced nutrition team, patients with gastrointestinal fistulae and leakage may not tolerate nutrition support and would have more severe pain due to the doctor’s negligence. Nutritional support can improve wound healing[1] and gastrointestinal permeability[2], decrease catabolic response to injury[3] and bacterial translocation[4], and achieve better clinical outcomes, including a decrease in complications and hospital stay time and cost saving[5-8]. It is necessary to find a perfect treatment for gastrointestinal fistulas. More studies have been done on the gastrointestinal fistula, especially on upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage. Absolute diet has been recognized as a routine diet during treatment of digestive fistula and leakage, and total parental nutrition (TPN) has been accepted by many doctors. We have successfully treated acute pancreatitis with “personal stage nutrition support” in the past 10 years. On this basis, we wonder if we can develop a new way of “personal stage nutrition support” for upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage.

Forty-three patients (27 males and 16 females) with upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage were selected from Zhongnan Hospital Wuhan University from January 2005 to November 2007. Their age was 20 to 72 years with a mean age of 51.3 ± 2.6 years. The occurrence of upper gastrointestinal fistula was due to emergency of trauma in 6 patients, post-operation for gastric ulcer in 13 patients, excision of duodenum ulcer in 8 patients. Sixteen patients had leakage after gastric perforation neoplasty. Patients with malnutrition or liver dysfunction induced by cancer, tuberculosis, severe anemia, malabsorption, hepatitis, hepatic cirrhosis and other severe cardiovascular disease were excluded. Endoscopy revealed the position of the fistula and leakage above the Vater ampulla. All patients had no severe abdominal cavity infection before surgery and were divided into group A and group B. Group A, that received personal stage nutritional support, served as an experimental group. Group B that received TPN served as a control group. Those who did not finish the treatment plan were excluded. All patients were numbered randomly. During the treatment, all data including electrolyte, liver function, renal function, blood analysis and complications were submitted to professor Yue-Ming He to decide whether it was necessary for the patients to quit from or receive the treatment plan.

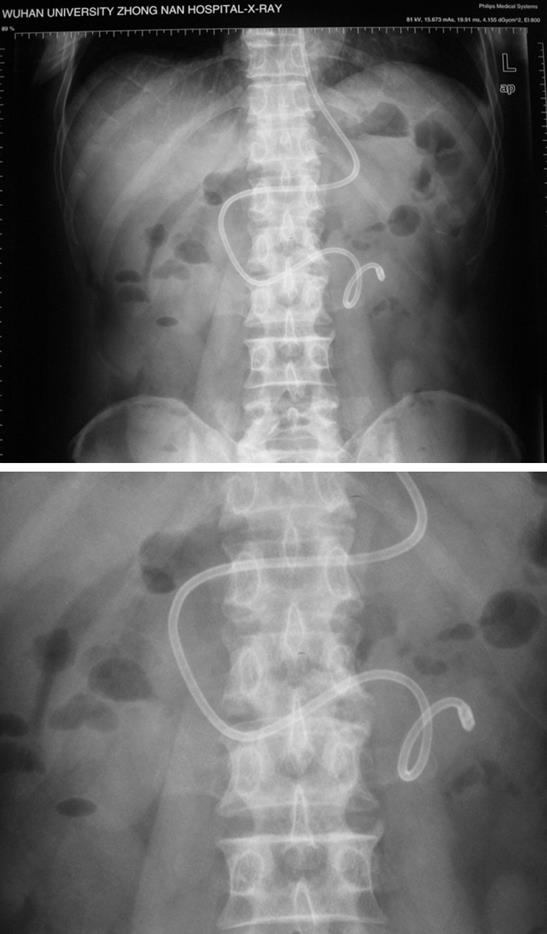

Nutrition support for group A was carried out in three steps: TPN stage, parental nutrition (PN) + enteral nutrition (EN) stage, and total enteral nutrition (TEN) stage. (1) TPN stage lasted 4-10 d (mean 7.8 ± 2.2 d). All the patients were asked to take absolute diet and supplied with 10-20 g/d albumin (Alb) and somatostatin. (2) PN + EN stage lasted 8-15 d (mean 11.6 ± 3.0 d). When the function of stomach and intestine recovered with the signal of outgas or defecation, EN was performed. In brief, one spiral nasojejunal feeding tube (Nutricia Company, Holland) was placed in the intestine below Treitz ligament (Figure 1) with the help of intestine enterokinesia after removal of the spiral coil guide wire. The distance from the tip of the tube to the orificium fistula was greater than 30 cm. The position of the nasojejunal tube should be confirmed by X-ray after 8-12 h since auscultation and pH aspiration techniques are inconclusive[9]. Nutrient substance was injected into jejunum through the spiral nasojejunal feeding tube. At the same time, we provided the patients with part parental nutrition as supplements. Chinese folk foods such as rice-water, fruit juice, vegetable soup, gravy soup, bean juice, as well as milk and peptison, could be used as nutrient substances and must be discontinued as soon as complications including stomachache, abdominal distension or diarrhea occurred. After we changed the speed and quantity of injection, all patients finished the stage. During this stage, somatotropin was also used. (3) TEN stage lasted 6-8 d (mean 7.5 ± 1.2 d). After completion of the PN + EN stage, we started the third stage, namely TEN stage which was started with closure of the fistula by endoscopic examination. After 35 d, the patients were asked to drink fresh water and take food. Gastrointestinal decompression and drain were performed through the spiral nasojejunal feeding tube in the first stage. At the same time, water and electrolyte disturbances must be prevented by changing ingredient and quantity of nutrient substances. Antibiotics (ceftriaxone sodium) and gastric acid secretion inhibitors (omeprazole) were given by intravenous drip in the first stage.

Patients in group B were given TPN through a central venous catheter which was inserted into the superior vena cava via one of the subclavian veins and advanced into the superior vena cava before and after operation. Basic heat energy was calculated depending on Harris-Benedict’s formula, the mean heat energy was 10460kJ (2000-2500 kcal) per day. Nutritional liquids containing glucose and amino acids were supplied with 8368 kJ (2000 kcal). Amino acids (9.4-14.1 g) were provided every day and 500-1000 mL of 10% intralipid was given to meet the need of fat. No hyperlipemia occurred in our patients. Gastrointestinal decompression and drain were carried out for 7 d. Antibiotics (ceftriaxone sodium) and gastric acid secretion inhibitors (omeprazole) were given by intravenous drip for 7 d.

The electrolyte, liver and renal function, and blood analysis were monitored for preventing electrolyte disturbances and infection. Fluid needs could usually be met by giving 30-35 mL/kg body weight although allowance must be made for excessive losses from drains and fistulae, etc. The feeds contain adequate electrolytes to meet the daily requirement of sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium and phosphate, although specific requirements may vary greatly.

Five hundred microliter serum segregated from peripheral blood was analyzed by chromatometry to measure the levels of Alb, TSF and pre-Alb. Liver function analysis was completed by Department of Laboratory, Zhongnan Hospital, Wuhan University

Twenty four-hour urine was collected to determine the level of nitrogen output as previously described[10] 1 d before operation and 1, 15 and 30 d after operation, respectively. Total nitrogen was calculated with the following formula: total nitrogen = nitrogen input-(nitrogen output + 3).

The complications, hospitalize time and expenditure were compared after recovery and discharge of the patients.

Data were analyzed with unpaired t test using SPSS 13.0. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Two patients were excluded from our study because they had to accept abdominal cavity drainage for severe abdominal cavity infection. As one of them could not tolerate nasojejunal feeding tube, his data were not included in our statistical analysis. The remaining 40 patients were divided into group A and group B, 20 in each group. Patients in group A received personal stage nutrition support, patients in group B underwent operation and received TPN. We found that there was no significant difference in the levels of Alb, TSF and pre- Alb between the two groups of patients before and after operation. The levels of Alb (g/L), TSF (g/L) and pre-Alb (mg/L) in patients of group B were lower than those in patients of group A (Table 1). No significant difference in nitrogen balance was found between the two groups (Table 2). Thirty days after operation, the levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST, U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT, U/L) and total bilirubin (Tbill, mol/L) were much higher in group B than in group A (Table 3), indicating that personal stage nutrition support can alleviate the impairment of liver function caused by extended TPN. The complications and the mean hospital stay time of the patients in group A were less than those of the patients in group B (Table 4). The mean cost for the patients in group A was lower than that for the patients in group B.

The traditional treatment of gastrointestinal fistula is surgical operation in combination with prolonged nutrition support. So it is very important to find the best way to support patients with enough nutrition which may achieve good results. Gastrointestinal fistula, especially upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage are hard to recover. TPN has been widely used in treatment of gastrointestinal fistula. Priorities of the management of gastrointestinal fistulas include restoration of blood volume and correction of fluid, electrolyte and acid-base imbalance, control of infection and sepsis with appropriate antibiotics and drainage of abscesses, as well as TPN and TEN[11].

TPN has many advantages. For example, it is accepted by patients more easily, the supplement of water and electrolyte are more convenient, nutrient substances are infused through veins, etc[12]. TPN is a form of nutritional support most suitable to patients with gut failure[13]. On the other hand, TPN provides sufficient heat and nutrient substances to meet the need of metabolism. Glyconeogenesis can be inhibited, thus keeping a positive nitrogen balance. In our research, there was no significant difference in nitrogen balance between the two groups. All the patients were switched from negative nitrogen balance to positive nitrogen balance. At the same time many disadvantages were discovered such as metabolic disturbance, catheter septicemia alteration in liver function and cholestasis[14], especially when patients received prolonged TPN, which is consistent with our findings. The levels of AST, ALT and Tbill were much higher in group B than in group A 30 d after TPN. In the stress condition, proper nutritional support may provide necessary nutrients, reduce clinical complications and promote patients’ recovery from illness[12]. TPN provides significant benefits to patients[15]. In the stress stage, all of our patients were given TPN. When the stress condition of patients improved, they should be supported with EN followed by TEN. Gramlich et al[16] reported that EN could significantly decrease the incidence of infectious complications and may cost less, and they believe that EN should be the first choice of nutritional support. Goonetilleke[17] holds that all patients should accept EN after operation. Zaloga[18] and Marik[19] believe that the gastrointestinal tract is the preferred route for nutritional support in hospitalized patients. Patients with a functioning gastrointestinal tract should be fed enterally. Patients with upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage have a functioning intestine and can receive EN through a spiral nasogastric feeding tube which can arrive at the upper jejunum enterokinesia. In our study, patients with upper gastrointestinal fistula could accept EN after the stress condition was over. EN has many advantages. For instance, it can relieve the burden on the liver and protect the liver against damage and infection and maintain the balance of visceral blood flow compared with TPN. Enteral nutrition after stress can maintain immunocompetence and gut barrier integrity, and promote wound healing and reduce septic complications[20]. Early enteral feeding can prevent enterogenic infection in severely burned patients[21]. However, EN also has many disadvantages leading to abdominal distension, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, etc, which are consistent with the findings in our study. It was reported that TPN can substantially improve the prognosis of gastrointestinal fistula patients by increasing the rate of spontaneous closure and improving the nutritional status of patients requiring repeat operations[11]. In the stress stage, EN is not suggested because a lot of digestive fluid is secreted in the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas which may destroy gastrointestinal fistula. Therefore, TPN was used in all of our patients in the first stage. However, the length of stress stage, nutrition state and recovery speed were all different in each patient. This is why we established the “personal stage nutrition support”. As soon as the stress stage was over, we could give the patients EN together with PN in the PN + EN stage. Satinsky[22] reported that all patients should be supported with PN + EN after operation. We suggest that even surgical patients could be provided with personal stage nutrition support including PN + EN. We should provide nutrition support in the three stages for patients with upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage. Since TPN and EN have their advantages and disadvantages, we should make use of their advantages as much as we possibly can. Significant differences were found in complications, hospitalized time and cost between the two groups. When EN and PN are applied, strategies should be adopted to optimize their benefits and minimize their potential harms. This is why we used personal stage nutrition support but not operation in treatment of patients with upper gastrointestinal fistula. We believe that it is feasible to cure upper gastrointestinal fistula with personal stage nutrition support.

Much research work has been done on gastrointestinal fistula, especially on upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage, but there are many discussions about how to provide nutrition for patients. Absolute diet has been accepted as a routine diet in the treatment of digestive fistula and leakage, and total parental nutrition (TPN) is widely used by many doctors. We tried to find a better treatment modality for upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage in this study.

Many randomized controlled clinical trials as well as meta-analysis and systematic reviews have been performed to compare enteral nutrition (EN) with parental nutrition (PN). However, no definite conclusion is available. Some people considered that EN with PN should be employed according to the state and development of disease.

In the present study, we, for the first time, put forward the concept of personal stage nutrition support and applied it in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage in combination with operation.

We have successfully treated acute pancreatitis with “personal stage nutrition support” in the last 10 years. On this basis, we wonder if we can develop a new treatment modality with “personal stage nutrition support” for patients with upper gastrointestinal fistula. A spiral nasojejunal feeding tube has been used for provision of enteral nutrition for several years outside of China.

The research provides a new treatment modality for upper gastrointestinal fistula and leakage with personal stage nutrition support. The new concept is interesting and informative. The paper is well organized except for correction of some errors in writing and punctuation.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Bernardino Rampone, Department of General Surgery and Surgical Oncology, University of Siena, viale Bracci, Siena 53100, Italy

S- Editor Zhong XY L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Schroeder D, Gillanders L, Mahr K, Hill GL. Effects of immediate postoperative enteral nutrition on body composition, muscle function, and wound healing. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1991;15:376-383. |

| 2. | Hadfield RJ, Sinclair DG, Houldsworth PE, Evans TW. Effects of enteral and parenteral nutrition on gut mucosal permeability in the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1545-1548. |

| 3. | Mochizuki H, Trocki O, Dominioni L, Brackett KA, Joffe SN, Alexander JW. Mechanism of prevention of postburn hypermetabolism and catabolism by early enteral feeding. Ann Surg. 1984;200:297-310. |

| 4. | Gianotti L, Alexander JW, Nelson JL, Fukushima R, Pyles T, Chalk CL. Role of early enteral feeding and acute starvation on postburn bacterial translocation and host defense: prospective, randomized trials. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:265-272. |

| 5. | Carr CS, Ling KD, Boulos P, Singer M. Randomised trial of safety and efficacy of immediate postoperative enteral feeding in patients undergoing gastrointestinal resection. BMJ. 1996;312:869-871. |

| 6. | Taylor SJ, Fettes SB, Jewkes C, Nelson RJ. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial to determine the effect of early enhanced enteral nutrition on clinical outcome in mechanically ventilated patients suffering head injury. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2525-2531. |

| 7. | Delmi M, Rapin CH, Bengoa JM, Delmas PD, Vasey H, Bonjour JP. Dietary supplementation in elderly patients with fractured neck of the femur. Lancet. 1990;335:1013-1016. |

| 8. | Kudsk KA, Croce MA, Fabian TC, Minard G, Tolley EA, Poret HA, Kuhl MR, Brown RO. Enteral versus parenteral feeding. Effects on septic morbidity after blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma. Ann Surg. 1992;215:503-511; discussion 511-513. |

| 9. | Stroud M, Duncan H, Nightingale J. Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. Gut. 2003;52 Suppl 7:vii1-vii12. |

| 10. | Thompson M, Owen L, Wilkinson K, Wood R, Damant A. A comparison of the Kjeldahl and Dumas methods for the determination of protein in foods, using data from a proficiency testing scheme. Analyst. 2002;127:1666-1668. |

| 11. | Dudrick SJ, Maharaj AR, McKelvey AA. Artificial nutritional support in patients with gastrointestinal fistulas. World J Surg. 1999;23:570-576. |

| 12. | Makhdoom ZA, Komar MJ, Still CD. Nutrition and enterocutaneous fistulas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:195-204. |

| 13. | Jeejeebhoy KN. Total parenteral nutrition: potion or poison? Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:160-163. |

| 14. | Ren JA, Mao Y, Wang GF, Wang XB, Fan CG, Wang ZM, Li JS. Enteral refeeding syndrome after long-term total parenteral nutrition. Chin Med J (Engl). 2006;119:1856-1860. |

| 15. | Jiang XH, Li N, Li JS. Intestinal permeability in patients after surgical trauma and effect of enteral nutrition versus parenteral nutrition. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1878-1880. |

| 16. | Gramlich L, Kichian K, Pinilla J, Rodych NJ, Dhaliwal R, Heyland DK. Does enteral nutrition compared to parenteral nutrition result in better outcomes in critically ill adult patients? A systematic review of the literature. Nutrition. 2004;20:843-848. |

| 17. | Goonetilleke KS, Siriwardena AK. Systematic review of peri-operative nutritional supplementation in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. JOP. 2006;7:5-13. |

| 18. | Zaloga GP. Parenteral nutrition in adult inpatients with functioning gastrointestinal tracts: assessment of outcomes. Lancet. 2006;367:1101-1111. |

| 19. | Marik PE. Maximizing efficacy from parenteral nutrition in critical care: appropriate patient populations, supplemental parenteral nutrition, glucose control, parenteral glutamine, and alternative fat sources. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:345-353. |

| 20. | Braunschweig CL, Levy P, Sheean PM, Wang X. Enteral compared with parenteral nutrition: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:534-542. |

| 21. | Peng YZ, Yuan ZQ, Xiao GX. Effects of early enteral feeding on the prevention of enterogenic infection in severely burned patients. Burns. 2001;27:145-149. |

| 22. | Satinsky I, Mittak M, Foltys A, Kretek J, Dostalik J. [Comparison various types of artificial nutrition on postoperative complications after major surgery]. Rozhl Chir. 2005;84:134-141. |