INTRODUCTION

A primary aortoenteric fistula (PAEF) is a rare but often life-threatening cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding[1–5]. PAEFs have a mortality rate of nearly 100% in the absence of surgical intervention, and diagnosis is not established preoperatively[2–5]. Diagnostic procedures are often non confirmatory and can sometimes impede urgently needed surgical intervention[346]. Although it is infrequent, gastrointestinal endoscopy may be a double-edged sword when PAEFs coexist with multiple bleeding sites[7]. Here, we report such a case in which the cause of death was massive gastrointestinal bleeding due to a PAEF after leaving the hospital.

CASE REPORT

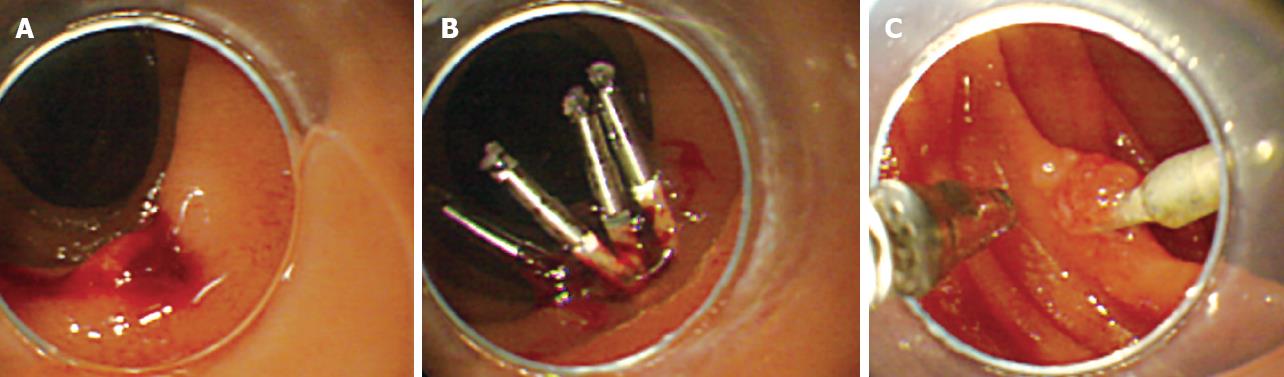

A 68-year-old man went to a hospital after suffering from melena for several days. He was conscious but looked pale. He had a blood pressure of 120/60 mmHg. His hemoglobin level was 5.7 g/dL and his hematocrit was 19.8%. An abdominal examination appeared normal, and no abdominal mass was observed. An emergency gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a bleeding ulcer in the second part of the duodenum (Figure 1A). Other potential sources of acute bleeding were excluded. The patient was diagnosed with a probable duodenal ulcer, which was the presumed source of his bleeding. Endoscopic hemoclipping was performed (Figure 1B), and the patient received a blood transfusion and hemostatic agents. Following these procedures, the patient had no signs of hemorrhaging and recovered from anemia. After a follow-up endoscopy on the 13th d (Figure 1C), the patient was discharged from the hospital. However, the following day, the patient complained of lumbago and abdominal distension. In the middle of the night, he suddenly entered into a state of shock, experienced a cardiac arrest, and was taken to the hospital. In the emergency room, a nasogastric tube was inserted and nasogastric aspiration was performed producing 880 mL of blood.

Figure 1 Endoscopic image showing a bleeding ulcer in the second part of the duodenum (A), the endoscopic clipping procedure revealing no other bleeding site detected by upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy (B), and follow-up gastrointestinal endoscopic view 12 d after hemostatic procedure (C).

Only one hemoclip remained on the scar of the duodenal ulcer.

Autopsy findings

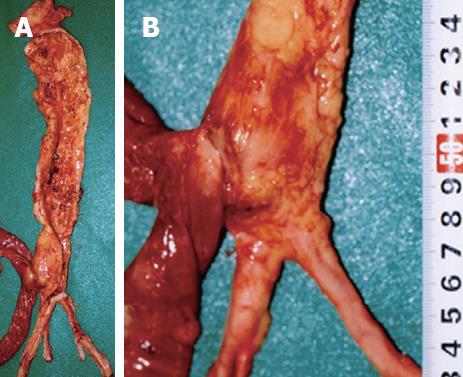

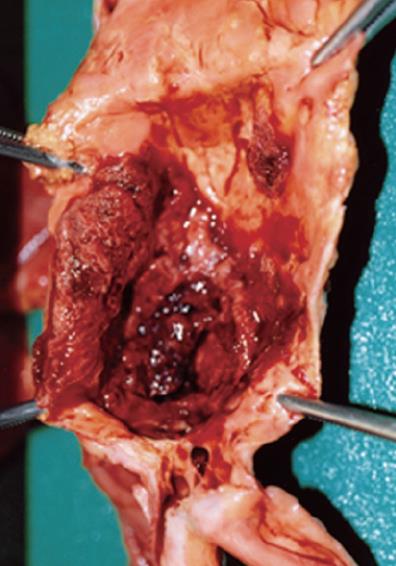

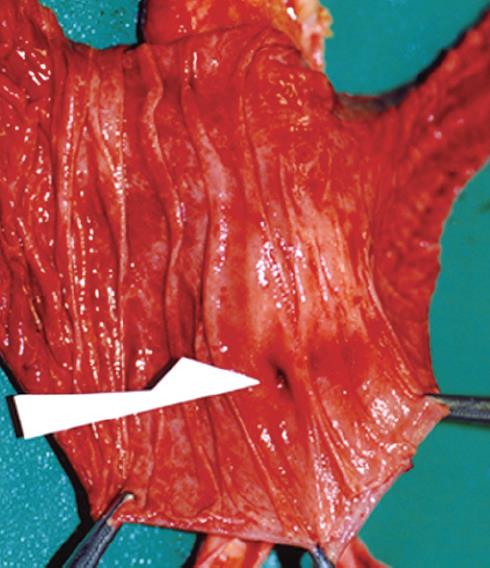

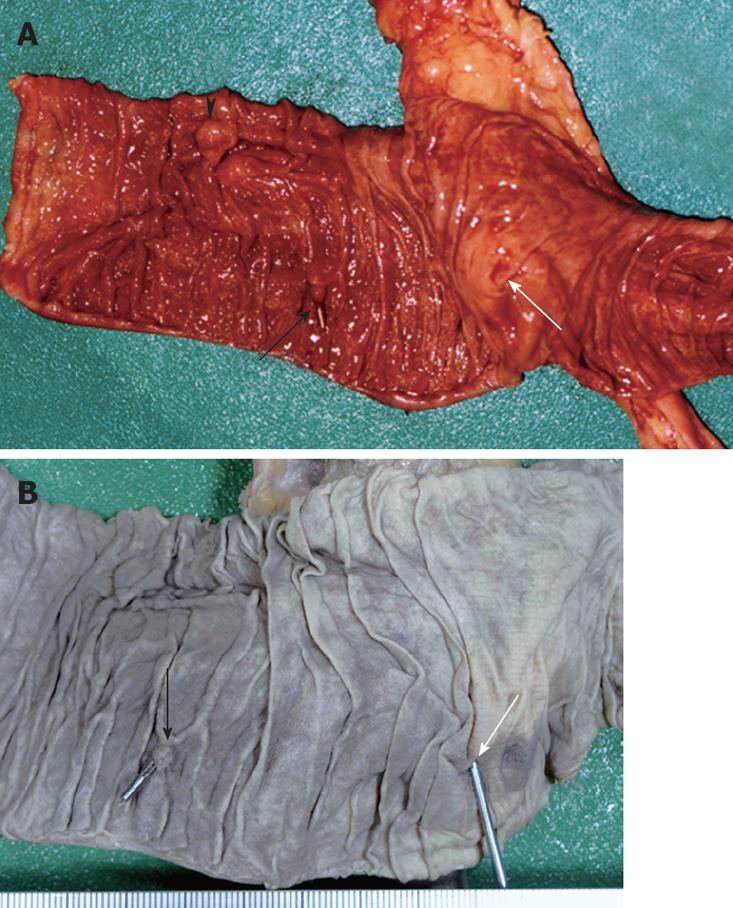

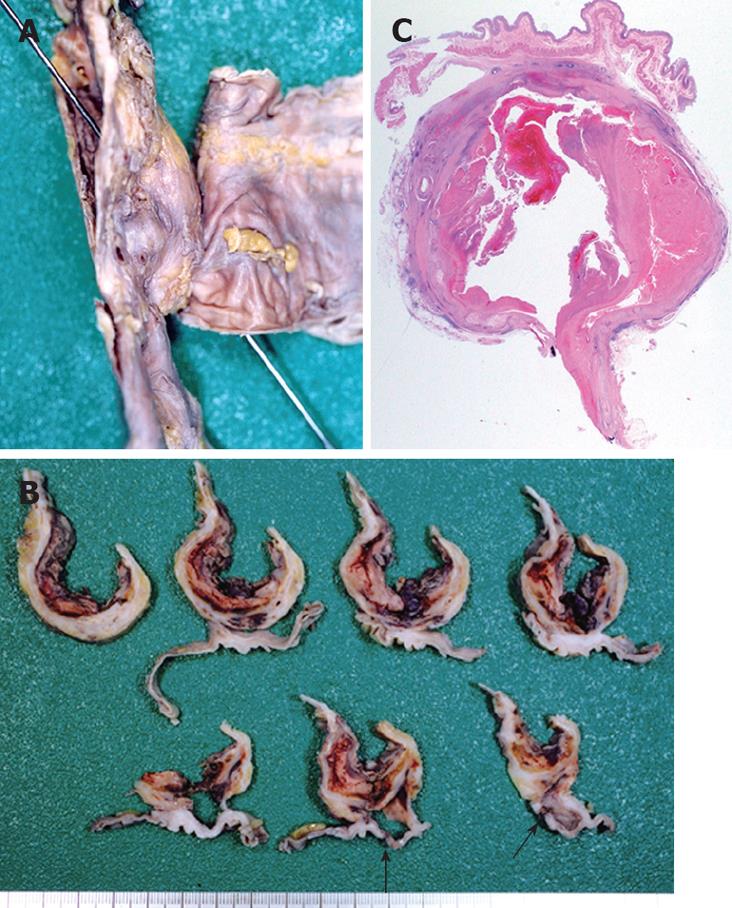

The patient measured 162 cm in height and weighed 58 kg. Postmortem hypostasis on the back was very slight. No petechiae were observed in the palpebral conjunctivae. External examination revealed no injuries except for those caused by clinical procedures performed in the emergency room. Internal examination revealed that the gastrointestinal tract was dilated and contained 2200 mL of clotted blood between the stomach and jejunum. No abdominal organ injury and blood were found in the abdominal cavity. An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) was located above the bifurcation of the aorta and resembled a fusiform swelling, 4 cm in diameter and 5 cm in length. An AAA with atherosclerosis thrust forward, adhering firmly to the digestive duodenal wall (Figure 2). The inferior mesenteric artery was hardly identified due to fibrous adhesion. The internal surface of the AAA had highly-calcified atheromatous ulcers covered with mural thrombus (Figure 3). A pinhole rupture was located on the third part of the duodenal mucosa (Figure 4) and fistulized into the adjacent AAA. A scarred ulcer with a hemoclip was observed on the second part of duodenal mucosa (Figure 5). No other origin of bleeding was found in the gastrointestinal tract.

Figure 2 The presence of a firm adhesion between the AAA and the digestive duodenal wall located on the third part of duodenum (A), and magnification of the firm adhesion between the anterior site of the abdominal aorta and the posterior serosa of the duodenum (B).

Figure 3 The AAA has severe atherosclerosis with calcification and clotted blood on the aneurysm inside the aortic lumen.

Figure 4 A rupture and the size of a pinhole with no degeneration or inflammation of the third part of the duodenal mucosa as indicated by the white arrow.

Figure 5 A scar on the clipped ulcer indicated by the black arrow, papilla Vater indicated by the black triangle, and a rupture on the third part of duodenal mucosa located in front of the firm adhesion indicated by the white arrow in the duodenal mucosa specimen (A), and a postclipping scar indicated by the black arrow and a rupture indicated by the white arrow in the formalin-fixed specimen of the duodenal mucosa (B).

The rupture was located approximately 6 cm from the anal side of the postclipping scar.

Microscopic investigations

Histological examination revealed a fibrous adhesion between the aorta and duodenal serosa. The aneurysm contained atheromatous degeneration covered by a mural thrombus with a layer of fibrin. The internal and external elastic membranes were destroyed and the media of the artery was thinned under the most advanced plaque. Fibroblast proliferation and granulation tissue were revealed in the adventitia of the aorta and perivascular tissue. Inflammation of the duodenum was more serious at the serosa, but there were no signs of inflammation of the duodenal mucosa (Figure 6). Because repair reaction of the aorta was broader than that of the duodenum, inflammation may originate out of the aorta.

Figure 6 Formalin-fixed duodenum and aorta specimen demonstrating a sonde inserted from the rupture on the duodenal mucosa to the inside of the aortic lumen (A), horizontal cross sections showing a firm adhesion between the aorta and its wall as well as a rupture (black arrow) on the third part of the duodenum (B); and a microphotograph of a horizontal cross section showing an adhesion between the duodenum and the aorta with atherosclerosis-contained clotted blood (C).

The histology of the duodenal appears normal (HE, × 5).

DISCUSSION

A PAEF, defined as a communication between the native aorta and gastrointestinal tract, is a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding[2389]. A large autopsy series reported an incidence of PAEF of 0.04%-0.07%[127]. A fistula most commonly originates from an AAA, of which 85% are atherosclerotic. AAA is a common disease among middle-aged and older subjects, and its clinical consequences depend on its location and size. The major complications of AAA include rupture into the peritoneal cavity, occlusion of a branch vessel and embolism from atheroma or mural thrombus. PAEF is the rarest complication of AAA. The most frequent site of a fistula is the third part of the duodenum, as in the current case[1–410]. The literature reports that PAEFs are often fatal, with a total mortality rate of 80%-100% and a perioperative mortality rate of 18%-63%[1–379–11]. However, the actual incidence and mortality rates are not known because many patients die of PAEFs before they have been correctly diagnosed[18].

The classical triad of symptoms, i.e. gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal pain, and a pulsating abdominal mass is overemphasized[134], as it occurs in less than 25% of PAEF cases[6]. The diagnosis of a PAEF is difficult because of its nonspecific and subtle clinical presentation[24]. However, PAEFs usually present with a herald bleeding prior to exsanguination[1–49]. Herald bleeding is usually minor and self-limiting, and it is probably due to a spasm of the intestinal wall musculature in response to sudden distention[13]. Bleeding can be further limited by hypotension and thrombus formation[1–3]. Consequently, excessive volume therapy and endoscopy may promote fatal exsanguination[112]. The time interval between a herald bleeding and exsanguination is known to range from hours to months[1–49]. The interval was about 2 wk in the current patient. When the patient dies of fatal exsanguination after going to the hospital due to a herald bleeding, his family may suspect an error in medical treatment.

Frequently, the choice of a diagnostic procedure is based on the clinical condition[135]. Diagnostic imaging techniques, such as contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and angiography, are useful investigation modalities for identifying PAEFs[1–4]. Even if there is limited bleeding at the examination, CT might reveal the size, location, and degree of calcification of an AAA. Fibrous adhesion between the aorta and duodenum might facilitate PAEF identification. In a hemodynamically stable patient with gastrointestinal bleeding, endoscopy is the preferred primary procedure which provides valuable information[1–37]. However, endoscopy rarely reveals confirmatory evidence of a PAEF because stable patients do not often have an active bleeding[121113]. Additionally, endoscopic visualization of a fistula that is present lower than the third part of the duodenum, which is the most common site of PAEF occurrence, is extremely difficult[2414]. In the clinical setting, the absence of identifiable bleeding lesions with initial gastrointestinal endoscopy is regarded by some as a strong indicator for laparotomy[313]. Recently, since the introduction of capsule endoscopy for clinical use, small bowel bleeding from the ampulla of Vater into the terminal ileum can be easily visualized and defined[15]. Capsule endoscopy, which noninvasively captures images of the gastrointestinal mucosa without any pressure load, might be the best strategy for identifying a PAEF. However, if upper endoscopy or colonoscopy detects other coexisting bleeding sites in PAEF patients, the findings may be misleading[346713]. Furthermore, concomitant gastrointestinal lesions are occasionally found in PAEF patients, and this incidence is 25% as indicated in previous series[571316]. In the current patient, a bleeding ulcer was identified as the source of the gastrointestinal bleeding. Hence, the possibility of a PAEF might have been overlooked. Ultimately, the key to early diagnosis of PAEF is an endscopist’s heightened index of suspicion[4513]. Endoscopists need to recognize PAEFs as a potential cause of gastrointestinal bleeding.