Published online Jul 28, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4480

Revised: June 3, 2008

Accepted: June 10, 2008

Published online: July 28, 2008

AIM: To investigate the utility of esophageal capsule endoscopy in the diagnosis and grading of esophageal varices.

METHODS: Cirrhotic patients who were undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for variceal screening or surveillance underwent capsule endoscopy. Two separate blinded investigators read each capsule endoscopy for the following results: variceal grade, need for treatment with variceal banding or prophylaxis with beta-blocker therapy, degree of portal hypertensive gastropathy, and gastric varices.

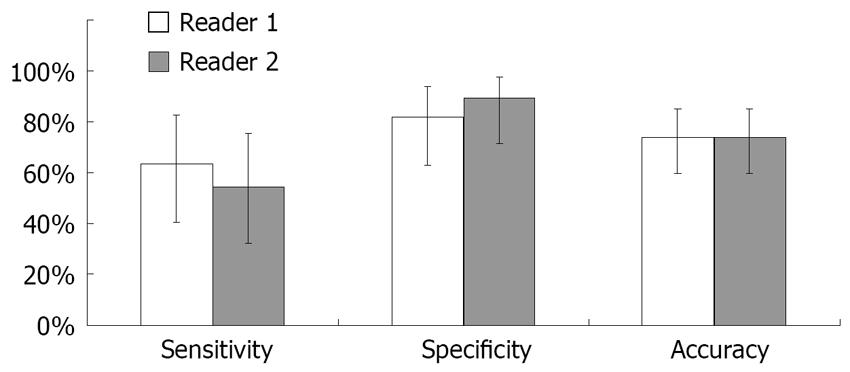

RESULTS: Fifty patients underwent both capsule and EGD. Forty-eight patients had both procedures on the same day, and 2 patients had capsule endoscopy within 72 h of EGD. The accuracy of capsule endoscopy to decide on the need for prophylaxis was 74%, with sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 82%. Inter-rater agreement was moderate (kappa = 0.56). Agreement between EGD and capsule endoscopy on grade of varices was 0.53 (moderate). Inter-rater reliability was good (kappa = 0.77). In diagnosis of portal hypertensive gastropathy, accuracy was 57%, with sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 17%. Two patients had gastric varices seen on EGD, one of which was seen on capsule endoscopy. There were no complications from capsule endoscopy.

CONCLUSION: We conclude that capsule endoscopy has a limited role in deciding which patients would benefit from EGD with banding or beta-blocker therapy. More data is needed to assess accuracy for staging esophageal varices, PHG, and the detection of gastric varices.

- Citation: Frenette CT, Kuldau JG, Hillebrand DJ, Lane J, Pockros PJ. Comparison of esophageal capsule endoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy for diagnosis of esophageal varices. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(28): 4480-4485

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i28/4480.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.4480

Cirrhosis affects 3.6 out of every 1000 adults in North America. A major cause of cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality is the development of variceal hemorrhage, a direct consequence of portal hypertension. The reported prevalence of esophageal varices in patients with chronic liver disease varies from 24% to 81%[1–3]. Variceal hemorrhage occurs in 25%-40% of patients with cirrhosis, and is associated with a mortality rate of up to 30%[12]. Accurate identification of patients with an increased risk of bleeding allows for primary prophylaxis to prevent variceal bleeding. Prophylactic use of beta-blockers has been shown to decrease the incidence of first variceal bleeding and death in patients with cirrhosis, and is currently the standard of care in patients who are at high risk for variceal hemorrhage[45]. Factors predictive of variceal hemorrhage include location of varices, size of varices, appearance of varices, clinical features of the patient, and variceal pressure[6].

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the standard of care for evaluation of varices. An EGD is currently recommended at diagnosis of cirrhosis, and then yearly screening for patients with no varices on initial EGD for patients with progression of their liver disease or every two years for those who remain stable[5]. In patients with small varices, endoscopy should be performed every year to assess for a change in size[7].

Currently, there is no universally accepted grading system for varices. Reliability of endoscopy is affected by inter-observer variability[89]. The subjective grading, invasiveness, risks of sedation, and cost of EGD has prompted a search for other alternatives. As of yet, no alternative had proven to be as accurate as EGD.

Several pilot studies have been published comparing capsule endoscopy (CE) to EGD for variceal screening. Eisen et al studied 32 patients, and found an overall concordance rate of 96.9% for the diagnosis of esophageal varices and 90.6% for the diagnosis of portal hypertensive gastropathy[10]. Lapalus et al performed unsedated EGD and capsule endoscopy in 21 patients, with an accuracy of 84.2% for the presence or absence of esophageal varices[11].

Herein, we report the results of a study designed to assess the ability of capsule endoscopy to correctly identify the presence of esophageal varices and related features of portal hypertension in patients undergoing screening or surveillance endoscopy, and to determine the need for treatment or prophylaxis of esophageal varices.

All patients enrolled were from the patient population of Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, California. Patients were eligible if they were scheduled to undergo EGD for screening or surveillance of esophageal varices. Screening was performed in patients with either biopsy-proven cirrhosis, or biochemical and imaging studies consistent with cirrhosis. Surveillance was performed in patients who had previously been diagnosed with esophageal varices via EGD and were repeating the test to assess for progression of varices. Patients who had previously undergone banding of esophageal varices were included in the study if they were stable and had not had a variceal hemorrhage for ≥ 6 mo. Consecutive patients scheduled for EGD as screening or surveillance of esophageal varices were screened for eligibility to participate. All patients were age > 18 years, able to give informed consent, and hemodynamically stable.

Exclusion criteria included dysphagia, known Zenker’s diverticulum, the presence of cardiac pacemaker or other implantable electro-medical devices, pregnancy, or a scheduled MRI within 7 d after capsule ingestion. Patients also were excluded if they had a history of or risk for intestinal obstruction, including any prior abdominal surgery of the gastrointestinal tract other than uncomplicated cholecystectomy or appendectomy.

All patients who consented underwent capsule endoscopy and EGD on the same day or within 72 h. The endoscopies were performed under moderate sedation by three staff hepatologists at Scripps Clinic. The hepatologists were blinded to the results of the capsule endoscopy, but not to the patient’s prior history or previous endoscopy findings. Photographs were taken of any pertinent findings at endoscopy and grading of varices was agreed to by all three physicians after unblinding.

EGDs and CEs were both graded by the following scale: F0, no varices; F1, small straight varices; F2, tortuous varices and < 50% of esophageal radius; F3, large and tortuous varices with or without red spots[612]. Presence or absence of high risk stigmata, defined as neovascularization or red or white spots was noted separately. Each observer decided whether or not treatment was indicated based on presence of F2 or F3 varices or the presence of high risk stigmata on any size varix. Portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) was graded on the following scale: none, mild (mucosal mosaic pattern), moderate (mosaic mucosal pattern with occasional red spots), or severe (mosaic mucosal pattern, extensive red or black spots, active oozing)[1314]. Portal hypertensive gastropathy was diagnosed on capsule endoscopy via photographs of any area of the gastric mucosa as it was not possible to assess the location of the visualized area. The presence or absence of gastric varices was noted separately, as well as other findings unrelated to portal hypertension such as esophagitis, gastritis (defined as erythema or erosions of gastric lining), peptic ulcer disease, or duodenal lesions.

Capsule endoscopy was administered in the following manner in all patients. After imbibing 100 mL of water with 0.6 mL of simethicone, patients lay supine and then ingested the pill with 5 mL of water without raising their head. Any difficulty with ingestion was recorded by the administrator, and patients were instructed not to speak after pill ingestion. After 2 min supine, they were raised to a 30 degree incline. After another 2 min they were raised to 60 degrees, and after 1 min at 60 degrees the patient imbibed a sip of water. They then sat up completely and imbibed another sip of water, at which time they were placed in the left lateral decubitus position in order to improve visualization of the fundus. Three minutes after being placed on their left side the patients were instructed to sit up or walk around for the remaining 12 min of the examination.

Capsule endoscopies were read by two separate investigators, who were blinded to EGD findings, patient medical history, and reading of the other investigator. Both capsule readers had prior experience in endoscopic evaluation and diagnosis of esophageal varices. Prior to the study, both readers underwent training as recommended by the capsule manufacturer, consisting of review of a CD Rom and participation in an online course, which included review of 10 cases of capsule endoscopy. Each CE was read twice by each investigator on two separate occasions at least 60 d apart. Capsule images were evaluated for the presence and grade of esophageal varices, the presence and grade of PHG, the presence of gastric varices, and any other findings. Esophageal transit time and time spent reading each examination was recorded.

One week after capsule ingestion, each patient was contacted by telephone to assess for symptoms of capsule retention. At that time, patient satisfaction was assessed. Patients were asked if they would be willing to undergo CE or EGD again, and which study they preferred.

Statistical analysis was performed to assess sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of CE versus EGD in determining need for prophylaxis or treatment. A weighted kappa scale was used to determine agreement of variceal grade by CE compared to EGD, as well as inter- and intra-observer agreement[14–17]. Inter-observer agreement was defined as comparing results from Reader 1 to results from Reader 2. Intra-observer agreement measured results from the first read and results from the second read of each reader independent of the other reader. The sample size of 50 was chosen because with these numbers one typically will expect a standard deviation of 0.10 and coefficients of variation of 15% or less.

The study was approved by the local institutional review board.

Fifty-five patients were screened to participate in the study. Five patients were not included: 2 patients refused, 1 patient had a history of an esophageal stricture, and 2 patients had history of surgery on the gastrointestinal tract. Fifty patients successfully underwent EGD and esophageal capsule endoscopy. In most cases, patients underwent CE on the same day as and just prior to EGD. There were two patients who underwent CE on a different day but within 72 h and two patients who underwent CE immediately after EGD. Median esophageal transit time was 249.5 s (range, 1-352 s). The esophageal transit times were as follows: 2 capsules 0-5 s, 15 capsules 5-60 s, and 33 capsules 60-352 s. Five patients (10%) had a mild amount of difficulty swallowing the capsule, and four patients (8%) had a moderate amount of difficulty, one of whom had to swallow it in a sitting position.

Demographics of the patients can be seen in Table 1. Thirteen patients (26%) were undergoing surveillance of varices and had a history of previous variceal banding; the remainder were undergoing screening examinations. The patients who were undergoing surveillance had not been banded for at least 6 mo, and previously had been obliterated. All patients had undergone banding in the past for history of variceal bleeding. Based on EGD findings, prevalence of esophageal varices was 66%: 17 patients had no varices, 16 patients with F1 varices, 15 patients with F2 varices, and 2 patients with F3 varices. 5 patients underwent banding at the time of EGD.

| Patient population (%) | |

| Male gender | 34 (68) |

| Average age | 58 (range, 25-74) |

| Average MELD1 | 9.48 (range, 6-23) |

| Average Child-Pugh | 6.8 (range, 5-13) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 40 (80) |

| Hispanic | 6 (12) |

| African American | 3 (6) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (2) |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | |

| Hepatitis C | 24 (48) |

| Hepatitis C and alcohol | 7 (14) |

| Alcohol | 6 (12) |

| Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | 6 (12) |

| Other2 | 7 (14) |

In determining need for prophylaxis using EGD as the gold standard, sensitivity of CE was 63% (95% CI, 0.40-0.83; SD, 0.04), specificity was 82% (95% CI, 0.63-0.94; SD, 0.03), and accuracy was 74% (95% CI, 0.59-0.85; SD 0.04; Figure 1). The accuracy was not improved when patients with prior banding were excluded or when patients with difficulty swallowing the capsule were excluded. Positive predictive value in this population was 73% (95% CI, 0.48-0.91; SD, 0.04) and negative predictive value was 74% (95% CI, 0.55-0.88; SD, 0.04). There was no association between time of esophageal transit of the capsule and accuracy of the results, assessed by splitting the group at the median time of 249 s and comparing the two groups. Inter-rater reliability for need for prophylaxis was 0.56 (moderate agreement). Intra-rater reliability was 0.61 (good) for Reader 1 and 0.41 (moderate) for Reader 2. For grade of varices, agreement between EGD and CE was 0.53 (moderate). Inter-rater reliability for grade of varices was 0.77 (good), and intra-rater reliability was 0.76 (good) for Reader 1 and 0.69 for Reader 2.

Two patients (4%) had gastric varices. One of these patients had gastric varices suspected on CE by Reader 2, and neither of the patients had large esophageal varices requiring primary prophylaxis. It was not possible to gauge the location of the varices based on the capsule photographs.

Forty-five patients (90%) had portal hypertensive gastropathy: 28 patients with mild disease and 17 patients with moderate disease. In determining the presence or absence of PHG, sensitivity was 96% (95% CI, 0.78-0.99) and specificity was 17% (95% CI, 0.05-0.39). Accuracy was 57% (95% CI, 0.41-0.71). Inter-rater reliability for presence of PHG was 0.61 (good).

Seventeen patients (34%) had other findings seen on EGD. Seven patients had gastritis seen on EGD, two of which were detected by CE. Two patients had Barrett’s esophagus; one was detected by Reader 1 and one was detected by Reader 2. Two patients had esophagitis seen on EGD but not on CE. One patient had gastric polyps and one had duodenal polyps seen on EGD, and neither was detected on CE. One patient had an esophageal ring seen on EGD that was also detected on CE by Reader 2. One patient had scarring from prior banding that was seen on EGD but not CE. 11 patients underwent biopsy at time of EGD: 10 to rule out H pylori and one for diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus.

There were no complications from either CE or EGD. Thirty-six patients (72%) were satisfied equally with EGD and CE. Thirteen (26%) preferred CE to EGD, and one patient preferred EGD to CE. There were no instances of capsule retention.

Complications of portal hypertension remain one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Up to 33% of cirrhotics will experience bleeding from varices, and 70% of these will be plagued with recurrent variceal bleeding[126]. In 1998, an AASLD single-topic symposium on portal hypertension devised the following current recommendations for variceal screening: EGD at time of diagnosis of cirrhosis, and if no varices were present, on a biyearly basis if liver function is stable, or yearly if liver function worsens, and yearly if small varices were present on initial screening[7]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of beta-blocker therapy for reduction of risk of variceal bleeding and related mortality, decreasing the risk of variceal bleeding by 50%[18–20]. Recent data have suggested that variceal banding is also effective as primary prevention of variceal bleeding in patients with high risk varices[18–21]. Despite these recommendations, compliance with screening has been quite poor. Arguedas et al in 2001 reported that just 46% of cirrhotic patients underwent variceal screening by EGD prior to referral for liver transplantation, despite having a diagnosis of cirrhosis for a median duration of 3 years[22]. Results of a survey of practicing gastroenterologists suggested an even lower screening rate of 39%[23].

Alternative methods to EGD have been studied for variceal screening, including transnasal endoluminal ultrasound[24], platelet count/spleen diameter ratio[25], multidetector computed tomography esophagography[26], and esophageal capsule endoscopy[101127]. To date, no method has proven accurate enough to replace EGD.

The results of our study are different from the two published pilot studies, showing a lower sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for esophageal capsule endoscopy. Because there is known variability in grading of varices by EGD[89], the accuracy of capsule endoscopy when measured against EGD may be wrong. We attempted to decrease this effect by verification of variceal grade diagnosed at endoscopy after unblinding by all physicians involved in the study, through inspection of photographs. Other possible reasons that our study results may vary include the small size of prior studies compared to ours. Our trial size was still somewhat small, but we balanced that expectation with the recognition that a much larger trial would be needed for confirmation of this as a pilot trial. Other confounders for the data could include the absence of complete industry funding in our study as opposed to the prior ones, and our relative lack of expertise with capsule endoscopy or other technical difficulties.

Concern has been raised regarding the utility of capsule endoscopy in patients who have previously undergone banding of esophageal varices. Patients were included in our study if they had not undergone banding for at least 6 mo. We chose to include these patients because we felt that varices would still be able to be diagnosed at esophageal capsule endoscopy. When patients with previous banding were excluded from analysis, our accuracy did not improve significantly. A total of 5 patients out of 13 who were undergoing surveillance for esophageal varices required repeat banding at the time of EGD. This underscores a limitation of capsule endoscopy: that patients with varices seen at diagnosis may then have to undergo EGD for therapy.

There has been some concern about the mixed results of capsule endoscopy use for evaluation of esophageal pathology, such as varices, Barrett’s esophagus, or esophagitis[27–29]. It is thought that the mixed results of capsule endoscopy may have to do with deviations from the standard ingestion procedure recommended by the manufacturer[30]. We note that in our study, all patients were able to successfully swallow the capsule, with only 9 patients having some difficulty, including two patients that needed to lift their heads from the supine position and one patient that had to ingest the pill in the sitting position. We feel that there is little chance these deviations influenced our results. When we looked at patient history of banding, time of esophageal transit, and reader experience/learning curve, none of these factors significantly changed the results of our study. We, therefore, feel that the accuracy reported here may be more reflective of what can be expected with capsule endoscopy use in community gastroenterology practice.

Esophageal capsule endoscopy has been designed specifically to look at the esophagus; there is no way to ensure that full inspection of the gastric mucosa and duodenum will occur, as it would with EGD. When screening for varices, this usually is not an issue. However, as in our study, there are patients who have gastric varices in the absence of significant esophageal varices that would require pharmacologic prophylaxis against bleeding. These patients may be missed if screening was done solely with capsule endoscopy. In addition, capsule endoscopy had poor accuracy for diagnosis of portal hypertensive gastropathy. Capsule endoscopy limits the patient to diagnosis only. In 11 of our patients, biopsies were performed for diagnosis of H pylori or Barrett’s esophagus. Obviously, these biopsies would not have been able to be performed if capsule endoscopy was the only diagnostic method used.

Given our results for capsule endoscopy, we are uncertain if its routine use can replace EGD at this time as a screening tool. It may be useful for those patients who are unable or unwilling to undergo upper endoscopy, but clinicians need to be cognizant of the possibility of a false negative result. At this time, we would recommend use of esophageal capsule endoscopy only in the setting of a clinical trial.

In conclusion, we feel that capsule endoscopy has a limited role in deciding which patients would benefit from EGD with banding or beta-blocker therapy in early cirrhosis, as well as for determining the specific grade of esophageal varices, PHG, or gastric varices. More data is needed to assess accuracy for staging esophageal varices, PHG, and the detection of gastric varices. Clinicians who choose to employ capsule endoscopy as part of their routine clinical practice should be cognizant of the lower accuracy for esophageal variceal screening.

Esophageal varices are found in up to 81% of patient with cirrhosis, and results in significant gastrointestinal bleeding in up to half of patients. In order to prevent variceal bleeding, screening is recommended with upper endoscopy every 1-3 years, with prophylaxis given to those patients with large varices. Esophageal capsule endoscopy is a new device designed to image the esophagus in a noninvasive way. The utility of esophageal capsule endoscopy in the diagnosis of esophageal varices is not known.

To date, two pilot studies have been published regarding the use of esophageal capsule endoscopy for the diagnosis of esophageal varices. These initial studies were performed in 32 and 21 patients, respectively, and showed high concordance and accuracy for the diagnosis of esophageal varices with capsule endoscopy (96.9% and 84.2%, respectively).

In this publication, 50 patients underwent upper endoscopy and esophageal capsule endoscopy. The capsule endoscopies were independently read by two blinded investigators. The accuracy of capsule endoscopy for diagnosis of esophageal varices was found to be 74% in determining the need for prophylaxis based on the presence of large varices. The sensitivity was 63% and the specificity was 82%. Inter-rater reliability was moderate for determining the need for prophylaxis. Intra-rater reliability was moderate for one reader and good for the other reader. 34% of patients studied had other findings seen at upper endoscopy that were not reliably diagnosed with capsule endoscopy, including gastric varices, gastric and duodenal polyps, esophagitis, and Barrett’s esophagus. Accuracy for diagnosis of portal hypertensive gastropathy was poor at only 57%.

Currently, the use of capsule endoscopy for variceal screening cannot be routinely recommended. Refinements to the capsule procedure may improve the accuracy in the future. Further studies are needed to verify these results.

This paper details the use of esophageal capsule endoscopy for the diagnosis of esophageal varices. Two pilots studies suggested that capsule endoscopy may be useful for detection of large varices. In this largest cohort to date, we found that capsule endoscopy has a poor sensitivity in detecting large varices requiring prophylactic therapy. In addition, there is also poor inter- and intra-observer agreement when using this method for grading esophageal varices. Finally, since three quarters of all patients do not prefer one method over the other, it appears that capsule endoscopy would have a limited role in diagnosis of esophageal varices.

| 1. | Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, Rinaldi V, De Santis A, Merkel C, Attili AF, Riggio O. Incidence and natural history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2003;38:266-272. |

| 2. | Sanyal AJ, Fontana RJ, Di Bisceglie AM, Everhart JE, Doherty MC, Everson GT, Donovan JA, Malet PF, Mehta S, Sheikh MY, Reid AE, Ghany MG, Gretch DR, Halt-C Trial Group. The prevalence and risk factors associated with esophageal varices in subjects with hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:855-864. |

| 3. | Zaman A, Hapke R, Flora K, Rosen H, Benner K. Prevalence of upper and lower gastrointestinal tract findings in liver transplant candidates undergoing screening endoscopic evaluation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:895-899. |

| 4. | de la Mora-Levy JG, Baron TH. Endoscopic management of the liver transplant patient. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1007-1021. |

| 5. | Qureshi W, Adler DG, Davila R, Egan J, Hirota W, Leighton J, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli R, Wheeler-Harbaugh J. ASGE Guideline: the role of endoscopy in the management of variceal hemorrhage, updated July 2005. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:651-655. |

| 6. | Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. The North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:983-989. |

| 7. | Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Burroughs AK, Pagliaro L, Makuch RW, Bosch J, Stiegmann GV, Henderson JM, de Franchis R. Portal hypertension and variceal bleeding: an AASLD single topic symposium. Hepatology. 1998;28:868-880. |

| 8. | Bendtsen F, Skovgaard LT, Sorensen TI, Matzen P. Agreement among multiple observers on endoscopic diagnosis of esophageal varices before bleeding. Hepatology. 1990;11:341-347. |

| 9. | Reliability of endoscopy in the assessment of variceal features. The Italian Liver Cirrhosis Project. J Hepatol. 1987;4:93-98. |

| 10. | Eisen GM, Eliakim R, Zaman A, Schwartz J, Faigel D, Rondonotti E, Villa F, Weizman E, Yassin K, deFranchis R. The accuracy of PillCam ESO capsule endoscopy versus conventional upper endoscopy for the diagnosis of esophageal varices: a prospective three-center pilot study. Endoscopy. 2006;38:31-35. |

| 11. | Lapalus MG, Dumortier J, Fumex F, Roman S, Lot M, Prost B, Mion F, Ponchon T. Esophageal capsule endoscopy versus esophagogastroduodenoscopy for evaluating portal hypertension: a prospective comparative study of performance and tolerance. Endoscopy. 2006;38:36-41. |

| 12. | Idezuki Y. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices (1991). Japanese Society for Portal Hypertension. World J Surg. 1995;19:420-422; discussion 423. |

| 13. | Thuluvath PJ, Yoo HY. Portal Hypertensive gastropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2973-2978. |

| 14. | Stewart CA, Sanyal AJ. Grading portal gastropathy: validation of a gastropathy scoring system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1758-1765. |

| 15. | Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull. 1968;70:213-220. |

| 16. | Fleiss JL, Levin BA, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley 1981; 384. |

| 17. | Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159-174. |

| 18. | Imperiale TF, Chalasani N. A meta-analysis of endoscopic variceal ligation for primary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 2001;33:802-807. |

| 19. | Schepke M, Kleber G, Nurnberg D, Willert J, Koch L, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Hellerbrand C, Kuth J, Schanz S, Kahl S. Ligation versus propranolol for the primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2004;40:65-72. |

| 20. | Lui HF, Stanley AJ, Forrest EH, Jalan R, Hislop WS, Mills PR, Finlayson ND, Macgilchrist AJ, Hayes PC. Primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial comparing band ligation, propranolol, and isosorbide mononitrate. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:735-744. |

| 21. | Khuroo MS, Khuroo NS, Farahat KL, Khuroo YS, Sofi AA, Dahab ST. Meta-analysis: endoscopic variceal ligation for primary prophylaxis of oesophageal variceal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:347-361. |

| 22. | Arguedas MR, McGuire BM, Fallon MB, Abrams GA. The use of screening and preventive therapies for gastroesophageal varices in patients referred for evaluation of orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:833-837. |

| 23. | Hapke R, Zaman A, Benner KG, Flora K, Rosen H. Prevention of first variceal hemorrhage-a survey of community practice patterns. Hepatology. 1997;26:A30 (abstract). |

| 24. | Kane L, Kahaleh M, Shami VM, Caldwell SH, Berg CL, Abdrabbo KM, Yoshida CM, Arseneau KO, Yeaton P. Comparison of the grading of esophageal varices by transnasal endoluminal ultrasound and esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:806-810. |

| 25. | Giannini EG, Zaman A, Kreil A, Floreani A, Dulbecco P, Testa E, Sohaey R, Verhey P, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Mansi C. Platelet count/spleen diameter ratio for the noninvasive diagnosis of esophageal varices: results of a multicenter, prospective, validation study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2511-2519. |

| 26. | Kim SH, Kim YJ, Lee JM, Choi KD, Chung YJ, Han JK, Lee JY, Lee MW, Han CJ, Choi JI. Esophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis: multidetector CT esophagography--comparison with endoscopy. Radiology. 2007;242:759-768. |

| 27. | Sanchez-Yague A, Caunedo-Alvarez A, Garcia-Montes JM, Romero-Vazquez J, Pellicer-Bautista FJ, Herrerias-Gutierrez JM. Esophageal capsule endoscopy in patients refusing conventional endoscopy for the study of suspected esophageal pathology. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:977-983. |

| 28. | Eliakim R, Yassin K, Shlomi I, Suissa A, Eisen GM. A novel diagnostic tool for detecting oesophageal pathology: the PillCam oesophageal video capsule. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1083-1089. |

| 29. | Eliakim R, Sharma VK, Yassin K, Adler SN, Jacob H, Cave DR, Sachdev R, Mitty RD, Hartmann D, Schilling D. A prospective study of the diagnostic accuracy of PillCam ESO esophageal capsule endoscopy versus conventional upper endoscopy in patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:572-578. |