Published online Jul 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4400

Revised: May 27, 2008

Accepted: June 3, 2008

Published online: July 21, 2008

Severe reactions to mesalamine products are rarely seen in pediatric patients. We report a case of a 12-year-old boy who had a severe cardiac reaction to a mesalamine product Asacol. Past medical history is significant for ulcerative colitis (UC) diagnosed at 9 years of age. Colonoscopy one week prior to admission revealed pancolitis. He was treated with Asacol 800 mg three times per day and prednisone 20 mg/d. He was subsequently admitted to the hospital for an exacerbation of his UC and started on intravenous solumedrol. He had improvement of his abdominal pain and diarrhea. The patient complained of new onset of chest pain upon initiating Asacol therapy. Electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed non-specific ST-T wave changes with T-wave inversion in the lateral leads. Echocardiogram (ECHO) revealed low-normal to mildly depressed left ventricular systolic function. The left main coronary artery and left anterior descending artery were mildly prominent measuring 5 mm and 4.7 mm, respectively. His chest pain completely resolved within 24-36 h of discontinuing Asacol. A repeat echocardiogram performed two days later revealed normal left ventricular function with normal coronary arteries (< 3.5 mm). Onset of chest pain after Asacol and immediate improvement of chest pain, as well as improvement of echocardiogram and ECG findings after discontinuing Asacol suggests that our patient suffered from a rare drug-hypersensitivity reaction to Asacol.

- Citation: Atay O, Radhakrishnan K, Arruda J, Wyllie R. Severe chest pain in a pediatric ulcerative colitis patient after 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(27): 4400-4402

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i27/4400.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.4400

Mesalamine is a well-known treatment for ulcerative colitis. Drug reactions to mesalamine are uncommon, and most often include skin rash and hypereosinophilia[1]. Severe reactions to mesalamine products are rarely seen in pediatric patients. Cardiac complications have been reported as a rare extraintestinal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and mainly manifest as pericarditis[2–4]. However, cardiac complications may be associated as a very rare drug reaction to 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) products[156]. The difficulty lies in distinguishing between these two etiologies. We herein report a case of a 12-year-old boy with ulcerative colitis who had a severe cardiovascular reaction to a mesalamine product, Asacol.

This is a 12-year-old boy with a past medical history significant for ulcerative colitis (UC) diagnosed at 9 years of age, along with psoriasis and arthritis. He was initially placed on steroids and Pentasa when he was first diagnosed. The Pentasa was discontinued after he developed a rash. It was difficult to distinguish his psoriasis from a potential drug reaction as a cause of the rash. He was subsequently weaned from his steroids after approximately 2 mo.

He presented to the hospital three years after his initial diagnosis with a two-month history of exacerbation of his UC. His symptoms continued to progress. He had 6-8 bloody stools per day 2 wk prior to hospital admission. Colonoscopy 6 wk into the flare revealed pancolitis. He was started on Asacol 800 mg three times per day and prednisone 20 mg once a day for his UC flare. The patient was subsequently admitted for worsening abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea as well as fever, fatigue, myalgia, and extremity pain. He also complained of new onset of severe chest pain progressively worsening since starting Asacol therapy. The chest pain was not related to exercise and not associated with palpitations, shortness of breath, syncope, pallor, cyanosis or altered by changes in posture or breathing.

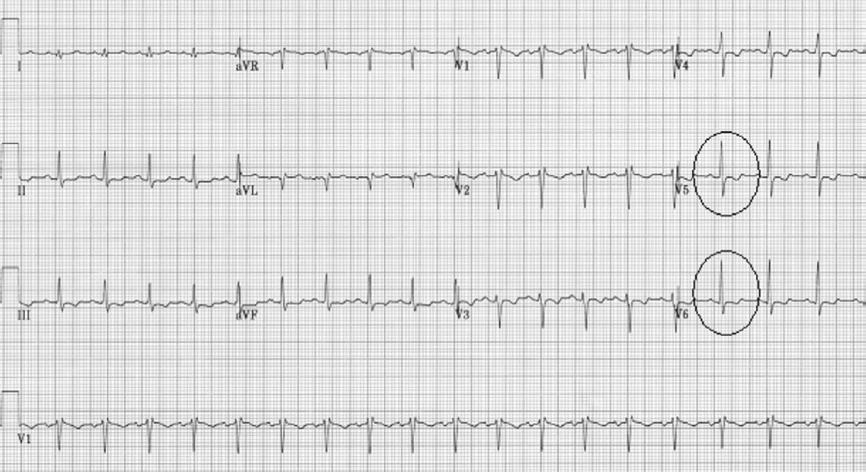

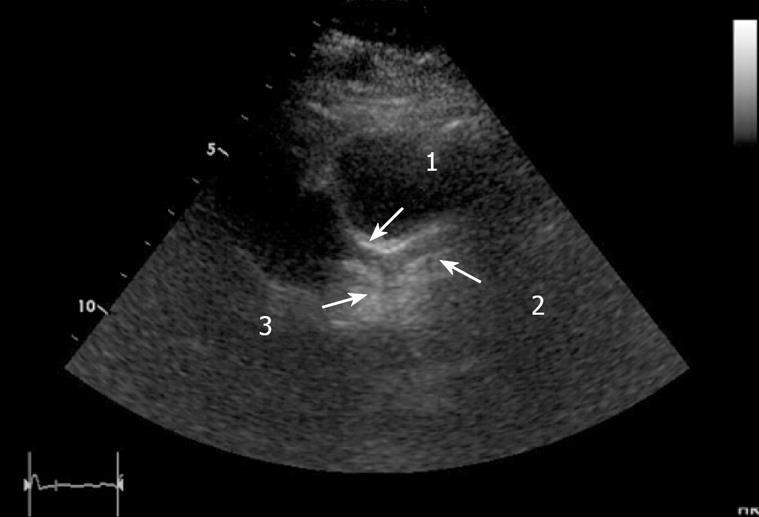

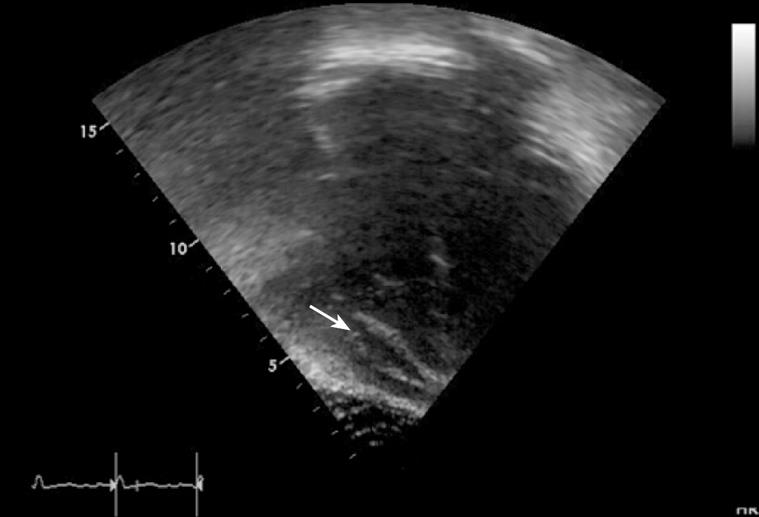

On admission, his vitals included a temperature of 38°C, pulse rate of 126 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute and a blood pressure of 107/65 mmHg. He was started on intravenous solumedrol 8 mg every 6 h with subsequent improvement of his abdominal pain and diarrhea. Chest pain, however, persisted and the chest pain worsened shortly after ingesting Asacol. Electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed and revealed non-specific ST-T wave changes with T-wave inversion in the lateral leads (Figure 1). Troponin T, CK-MB, Brain Natruritic Peptide, and CRP levels were ordered to evaluate for possible pericarditis or a myocardial abnormality. The results of this lab work were normal. Echocardiogram (ECHO) revealed low-normal to mildly depressed left ventricular systolic function. Calculated shortening fraction was 26% and left ventricular size was within normal limits. The left main coronary artery and left anterior descending artery were mildly prominent measuring 5 mm and 4.7 mm, respectively (Figure 2). The ECHO also revealed trivial circumferential pericardial effusion that was hemodynamically insignificant (Figure 3). A spiral CT scan ordered to evaluate for possible pulmonary embolism in the setting of an elevated d-dimer was unremarkable except for a small amount of pericardial fluid.

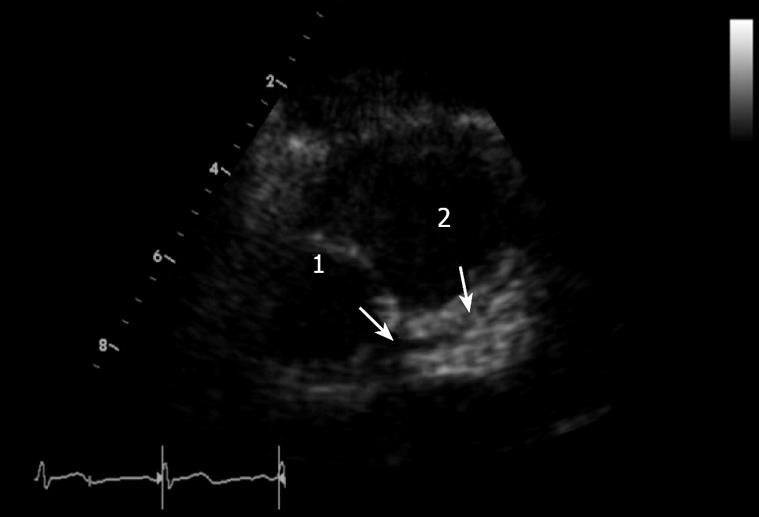

The patient’s chest pain completely resolved within 24 h after discontinuation of Asacol. A repeat echocardiogram performed two days later revealed normal left ventricular function with a shortening fraction of 33%, normal coronary arteries (< 3.5 mm) and a trivial pericardial effusion. The patient was subsequently discharged from the hospital on prednisone and methotrexate. His UC remained in remission upon follow-up by his pediatric gastroenterologist 2 mo after hospital discharge. An ECHO and ECG were also repeated in the follow-up 2 mo after hospital discharge, revealing continued resolution of coronary artery dilation (Figure 4). The ECG was normal without the S-T wave abnormality noted 2 mo earlier.

Mesalamine has been found to be a beneficial medication in the treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis. The mechanism of action of mesalamine is unknown; however, it is thought to exert its action topically as opposed to systemically. Mucosal production of arachidonic acid metabolites, through both the cyclo-oxygenase and the lipoxygenase pathways, is thought to be increased in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Mesalamine acts by a variety of mechanisms which include blocking cyclo-oxygenase thereby inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, reducing antioxidant and pro-inflammatory cytokine synthesis, reducing lymphocyte metabolism and reducing expression of adhesion molecules. All these work to decrease inflammation in the colon[78].

Chest pain along with electrocardiographic and echocardiogram findings in a pediatric patient on a 5-ASA product should alert the physician to the possibility of drug reaction. We have presented a pediatric patient with ulcerative colitis who developed cardiac signs and symptoms associated with pericarditis soon after starting a 5-ASA product. Determining the etiology of pericarditis in this setting can be complex as this presentation has been reported as a rare extraintestinal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease[2–4]. Chest pain may be associated with other more common gastrointestinal conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Chest pain in IBD may also be caused by respiratory infection and pleural inflammation which were ruled out in our patient. Patients with IBD have a higher propensity to develop pulmonary embolism (PE) and patients often present with acute onset of chest pain[4]. The normal spiral chest CT ruled out PE in our patient.

In our case, there was a temporal relationship between the onset of the chest pain and the administration of Asacol. The characteristics of the chest pain were not typical of pericarditis but the ST-T wave changes and the pericardial effusion which resolved after discontinuation of the Asacol were suggestive of the diagnosis. Normal troponin and CKMB levels do not support the diagnosis of myocarditis, although there was a mild but clear change in ventricular systolic function which also resolved after the Asacol was stopped. It is unclear why the coronary arteries were mildly prominent at the time of the diagnosis, which would suggest a vasculitis process such as Kawasaki disease.

This case illustrates the importance of eliciting a thorough medical history and being aware of the timing when new medications are started. It is imperative that any new onset of chest pain, especially in this setting, should be evaluated via cardiac enzymes, EKG and echocardiogram to quickly diagnose any complication caused by either the inflammatory bowel disease itself or a rare adverse drug reaction.

| 1. | Waite RA, Malinowski JM. Possible mesalamine-induced pericarditis: case report and literature review. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:391-394. |

| 2. | Bansal D, Chahoud G, Ison K, Gupta E, Montgomery M, Garza L, Mehta JL. Pleuropericarditis and pericardial tamponade associated with inflammatory bowel disease. J Ark Med Soc. 2005;102:16-19. |

| 3. | Hyttinen L, Kaipiainen-Seppanen O, Halinen M. Recurrent myopericarditis in association with Crohn's disease. J Intern Med. 2003;253:386-388. |

| 4. | Su CG, Judge TA, Lichtenstein GR. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:307-327. |

| 5. | Ishikawa N, Imamura T, Nakajima K, Yamaga J, Yuchi H, Ootsuka M, Inatsu H, Aoki T, Eto T. Acute pericarditis associated with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) treatment for severe active ulcerative colitis. Intern Med. 2001;40:901-904. |

| 6. | Iaquinto G, Sorrentini I, Petillo FE, Berardesca G. Pleuropericarditis in a patient with ulcerative colitis in longstanding 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1994;26:145-147. |

| 7. | Stein RB, Hanauer SB. Comparative tolerability of treatments for inflammatory bowel disease. Drug Saf. 2000;23:429-448. |

| 8. | Nielsen OH, Munck LK. Drug insight: aminosalicylates for the treatment of IBD. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:160-170. |