INTRODUCTION

Recurrence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a serious problem of HCV positive patients receiving liver transplantation, because it has been universally documented as the leading cause of allograft destruc-tion[12]. Although interferon (IFN) based therapy in combination with ribavirin for recurrent HCV infection has been widely accepted after liver transplantation, it induces various adverse effects related to bone marrow suppression such as thrombocytopenia and leukopenia, resulting in its interruption. Until recently, no approved treatment for thrombocytopenia in patients with HCV infection is available except for splenectomy or partial splenic embolization (PSE). However, it was most recently reported that the efficacy of eltrombopag, an orally active thrombopoietin-receptor agonist, for thrombocytopenia in patients with cirrhosis is associated with hepatitis C[3]. At present, this drug is not available in our country, and thus splenectomy is the treatment of choice to overcome this problem. Kishi et al[4] performed splenectomy concurrently with liver transplantation for all HCV-positive liver transplant patients. However, the indication for concomitant splenectomy still remains controversial.

As for splenectomy, laparoscopic splenectomy (LS) is employed as the minimal invasive surgery for various diseases including a normal-size spleen in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) as well as a huge-size spleen in hypersplenism due to liver cirrhosis[5]. It is believed that LS is relatively contra-indicated for patients with previous abdominal surgery, especially with upper abdominal surgery[6]. However, it was reported that the incidence of adhesion after organ transplantation is very low[78]. Wasserberg et al[9] revealed that post-surgical adhesion formation is significantly reduced in rats receiving tacrolimus immunosuppression after intestinal transplantation.

We therefore performed LS in a female patient with recurrent HCV infection after living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT), which did not lead to any complications. She developed severe thrombocytopenia after antiviral therapy using IFN. This is the first case of LS after LDLT.

CASE REPORT

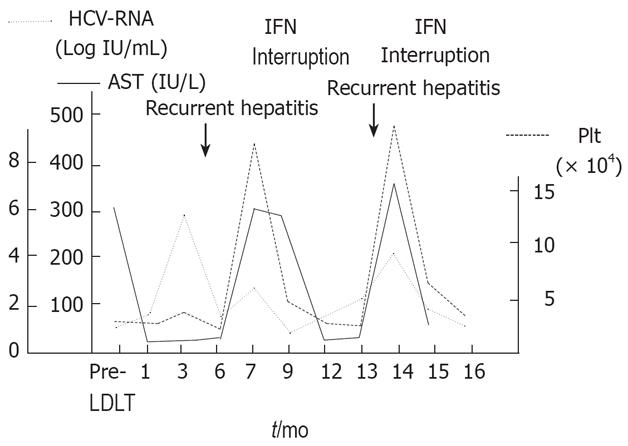

A 60-year-old female received LDLT with an ABO identical left lobe graft from her second son for liver failure due to hepatitis C-related cirrhosis at our institution. She was discharged without any postoperative complications. Six months after LDLT, however, her liver function was elevated and she was diagnosed as recurrent HCV infection by liver biopsy. IFN (alpha 2b) monotherapy (3 mega units, 3 times a week) was started 7 mo after LDLT and the levels of liver enzyme and HCV-RNA were notably improved. After 11 mo, however, her platelet count decreased to 32 000/&mgr;L, and thus INF treatment was discontinued. After interruption, her liver enzyme and HCV-RNA levels were remarkably elevated again 13 mo after LDLT. IFN therapy was started again when her platelet count was 70 000/&mgr;L and discontinued when her platelet count decreased to 39 000/&mgr;L (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Changes in serum levels of AST, HCV-RNA and platelet after LDLT.

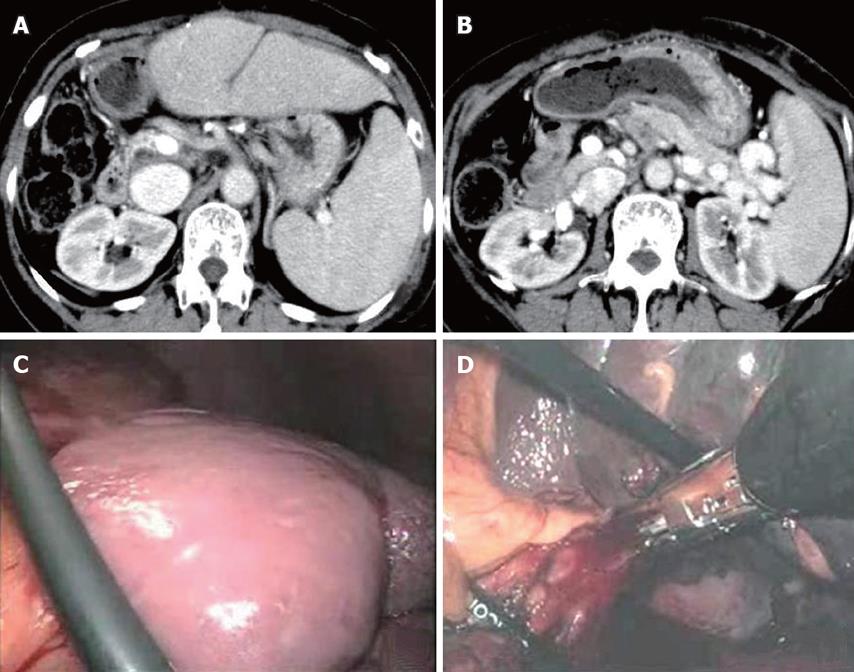

She was then admitted to our institution to receive splenectomy for thrombocytopenia 15 mo after LDLT. At admission, her laboratory test showed elevated levels of liver and biliary enzymes (157 IU/L AST, 184 IU//L ALT, 201 IU/L γ-GTP, 3.5 mg/L T-Bil, 2.7 mg/L D-Bil) and viral load of HCV-RNA was 5.4 LogIU/mL (genotype 1b). An abdominal enhanced CT demonstrated the enlarged spleen of 140 mm in maximum diameter and collateral vessels derived from the splenic vein (Figure 2A-B).

Figure 2 Abdominal enhanced CT showing splenomegaly with 140 mm in maximum diameter (A) and development of collateral veins around the splenic vein (B), no peritoneal adhesion to abdominal wall and around the spleen (C), and splenic hilum stapled with linear staplers (D).

We decided to perform LS even after LDLT, because the trial of LS was acceptable since LS is potentially successful because the operation filed of LDLT is mainly the right upper abdomen and the mobilization of spleen from the retroperitoneum under laparoscopic approach as much as possible makes a skin incision smaller even if LS is converted to open surgery. In addition, as LS after LDLT is not widely recognized and also has significant short term and long term considerable risks such as infectious complications, we gave the patient sufficient information about splenectomy.

The patient was placed at a right semidecubitus position under general anesthesia. The pneumo-peritoneum was introduced with the open Hasson's technique at the left lateral to the umbilicus and intra-abdominal findings did not show any adhesion to abdominal wall and around the spleen (Figure 2C). Thus, we started dissection of the splenocolic ligament and parietal peritoneum using the vessel sealing system (Ligasure AtlasTM) from the lower pole to the upper pole through the lateral side of spleen. After enough mobilization of the spleen, we stapled the splenic hilum with linear staplers (Figure 2D) and delivered the crushed spleen from the extended wound. The operation time was 2 h and 32 min and the amount of bleeding was 72 g. The weight of spleen was 260 g.

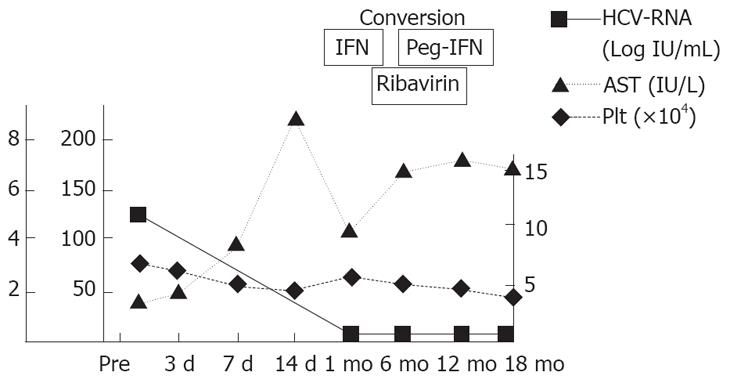

After splenectomy, her platelet count immediately increased and we could restart IFN monotherapy from postoperative day (POD) 7. Furthermore, since her platelet count increased to 225 000/&mgr;L on POD 14, we could convert IFN monotherapy to combination therapy of IFN (convert to peg-IFN 1 mo after operation) and ribavirin, resulting in no detectable viral marker 18 mo after LS and achievement of sustained viral response (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Changes in serum levels of AST, HCV-RNA and platelet count after operation.

DISCUSSION

Since Delaitre[10] performed the first laparoscopic splenectomy (LS) in the last decade, it has gained more and more respect because of its minimal invasion. Similarly to other laparoscopic procedures, it is characterized by shorter hospital stay, lower perioperative complication rate, better cosmetic result and earlier return to full working activity, which are the most important advantages over the open approach. In recent years, extension of its indications has been noted and this operation has been employed for diseases with normal size spleen such as ITP and huge size spleen such as hypersplenism related to liver cirrhosis. Furthermore, patients with thrombocytopenia caused by IFN therapy for recurrent HCV infection are good candidates for LS in order to overcome this problem[511]. Kent et al[5] reported that patients undergoing LS for thrombocytopenia associated with IFN therapy can improve their thrombocytopenia and their platelet count remains above 100 000/&mgr;L during subsequent pegylated-IFN therapy. However, no reports are available on successful LS after LDLT for the improvement of thrombocytopenia, as a result of PubMed search using laparoscopic splenectomy and liver transplantation as the key words.

It was reported that concomitant splenectomy with LDLT is necessary to prevent the progression of thrombocytopenia caused by postoperative antiviral therapy[412]. On the other hand, it is well known that concomitant splenectomy with LDLT induces several severe complications, such as postoperative portal vein thrombosis, re-bleeding, increasing intraoperative bleeding, and severe infection[1314]. Therefore, indications for concomitant splenectomy should be decided carefully. Although we perform splenectomy concurrently with LDLT to modulate portal venous pressure, especially when the portal venous pressure is over 20 mmHg after reflowing[15], we do not perform concomitant splenectomy for introduction of IFN therapy routinely at present.

Sohara et al[11] have reported the efficacy of PSE on overcoming IFN-related thrombocytopenia after liver transplantation. But in our hospital, LS is regarded as the first-line treatment for thrombocytopenia in patients with cirrhosis associated with hepatitis C, because PSE induces various severe complications, such as abscess of spleen, persistent fever, severe abdominal pain and the efficacy of PSE lasts for only one year and it is necessary to perform several times of PSE for good results[16–18].

Although LS has been accepted as a minimum invasive method, abdominal surgery used to be a relative contraindication to LS because of some complications related to peritoneal adhesions including other organ injury[6]. DeRoover[19] reported the first case of LS after orthotopic liver transplantation and described mild peritoneal adhesion found at intra-operation. In addition, various laparoscopic surgeries including incisional hernia repair, proctocolectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass after liver transplantation have been successfully performed in recent years[20–22] with a very low incidence of adhesion[7–9]. We successfully performed LS after LDLT.

In conclusion, LS can be performed safely even after LDLT, and LS after LDLT is a feasible and less invasive modality for thrombocytopenia caused by antiviral therapy.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Vincent Lai, Derby NHS Foundation

Trust, Utooxeter Road, Derby DE22 3NE, United Kingdom;

Dr. Raymund Rabe Razonable, Division of Infectious

Diseases, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester 55905,

United States; Dr. Byung Chul Yoo, Professor, Division

of Gastroenterology, Department of M, Samsung Medical

Center,SungKyunKwan University School of Medicine, 50

Irwon-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul 135710, Korea