Published online Jul 14, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4185

Revised: June 17, 2008

Accepted: June 24, 2008

Published online: July 14, 2008

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of endoscopic treatment in patients who undergo OLTx or LRLTx and develop biliary complications.

METHODS: This is a prospective, observational study of patients who developed biliary complications, after OLTx and LRLTx, with duct-to-duct anastomosis performed between June 2003 and June 2007. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was considered unsuccessful when there was evidence of continuous bile leakage despite endoscopic stent placement, or persistence of stenosis after 1 year, despite multiple dilatation and stent placement. When the ERCP failed, a percutaneous trans-hepatic approach (PTC) or surgery was adopted.

RESULTS: From June 2003 to June 2007, 261 adult patients were transplanted in our institute, 68 from living donors and 193 from cadaveric donors. In the OLTx group the rate of complications was 37.3%, while in the LRLTx group was 64.7%. The rate of ERCP failure was 19.4% in the OLTx group and 38.6% in LRLTx group. In OLTx group, 1 patient was re-transplanted and 8 patients died. In the LRLTx group, 2 patients underwent OLTx and 8 patients died. The follow-up was 23.3 ± 13.13 mo and 21.02 ± 14.10 mo, respectively.

CONCLUSION: Although ERCP is quite an effective mode of managing post-transplant bile duct complications, a significant number of patients need other types of approach. Further prospective studies are necessary in order to establish whether other endoscopic protocols or new devices, could improve the current results.

- Citation: Tarantino I, Barresi L, Petridis I, Volpes R, Traina M, Gridelli B. Endoscopic treatment of biliary complications after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(26): 4185-4189

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i26/4185.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.4185

Biliary complications are the most frequent problem after liver transplantation. The available data show that the rate of biliary complications in transplant recipients ranges between 8% and 20%. This rate of complications is higher for living-related liver transplantation (LRLTx) vs orthotopic liver transplantation (OLTx)[12]. Biliary complications may include: anastomotic stricture, biliary leaks, stones or debris and Oddi dysfunction. Often patients develop more than one complication[3]. Whether the rate of biliary complications is lower in patients with the duct-to-duct anastomosis than with choledoco-jejunum anastomosis is unknown. However, the duct-to-duct anastomosis is usually preferred because it can easily be reached with an endoscopic procedure, which the published data has proven to be very effective[1].Early diagnosis is crucial, as the treatment may improve graft function and help to avoid repeated surgery. Patients often show unspecific symptoms, such as fever or anorexia, even without pain[3]. More often patients are asymptomatic but have high liver functions test (LFT) values and/or bilirubin levels. Abdominal ultrasonography often shows no biliary dilatation, while liver biopsy (used in many centers) does not appear to be conclusive in this type of patient[4]. Interpreting the histologic findings of bile duct damage and bile flow impairment can be confusing. Typical findings of extra-hepatic bile duct obstruction include portal edema, proliferation of ducts and ductules, neutrophilic cholangitis, and hepatocanalicular cholestasis. However, concomitant histologic findings of cellular rejection from associated biliary stasis or infection can confuse the primary diagnosis and lead to a misdiagnosis of rejection[4]. When comparing histologic features from patients with and without biliary strictures, Campbell et al[5] found that cholangitis was the only biopsy feature significantly associated with a documented stricture. Therefore, a low threshold to obtain an early cholangiogram should exist. Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has shown a 93% diagnostic accuracy, with sensitivity and specificity over 90% and a PPV equal to 86%[6]. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) remains the gold standard when suspicion of biliary complications is high, and allows a direct approach to interventional procedures[3].Some studies have already been published on the endoscopic treatment of biliary complications, and show a success rate of approximately 70%-80% of cases[6–10].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of endoscopic treatment in patients who undergo OLTx or LRLTx and develop biliary complications.

This is a prospective, observational study of patients who developed biliary complications after cadaveric and living-related liver transplants (OLTx and LRLTx) with duct-to-duct anastomosis between June 2003 and June 2007.

To overcome the gap between the number of donations and number of patients listed for OLTx, our institute decided to accept “extended criteria donors” (ECD). An ECD was defined as: age > 60 years; macrovesicular steatosis > 30%; prolonged intensive care unit stay (> 7 d); hemodynamic risk factors, including under this term the following conditions: prolonged hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 60 mmHg for more than 2 h); use of dopamine > 10 mcg/kg per min for more than 6 h to sustain blood pressure; need for 2 inotropic drugs to sustain donor blood pressure for more than 6 h; cold ischemic time > 12 h; and hypernatraemia (Na peak > 160 Meq/L) before aortic cross clamp.

With regard to the diagnosis of biliary complications, abdominal ultrasonography with Doppler was routinely performed in order to rule out vascular alterations, but indication for ERCP was based on increased LFT values and MRCP for the OLTx group. In the LRLTx group all patients had a T-tube insertion during the transplant, so the diagnosis of biliary complications was made on T-tube cholangiogram.

Separate databases were created for patients who underwent OLTx and LRLTx. For each patient, the following data were recorded: demographic information and clinical data, type of biliary complication, time of onset, type of endoscopic treatment, number of procedures received, recovery-time, need for other treatment, surgery or re-OLTx, and final outcome.

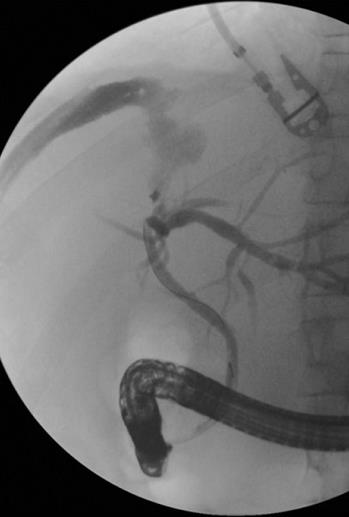

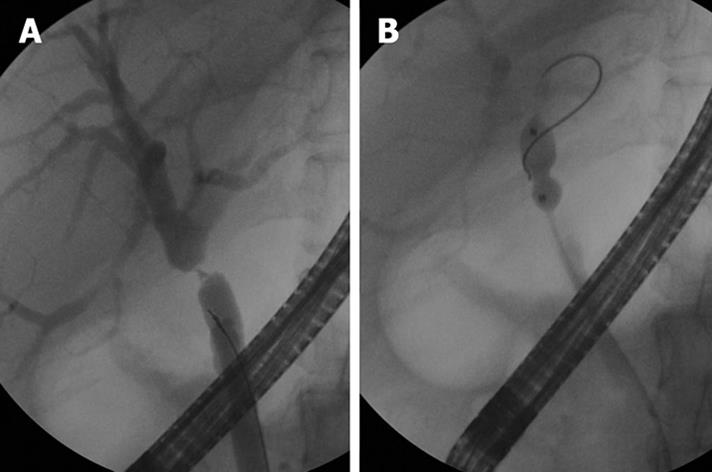

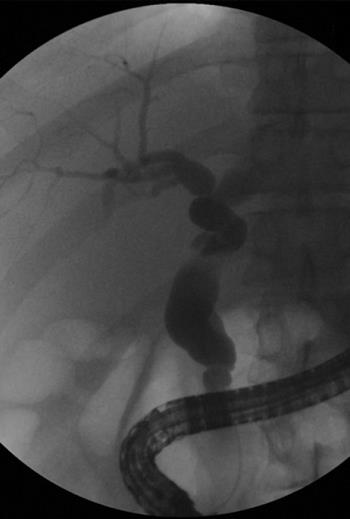

All biliary complications were initially treated with standard ERCP, performing the conventional procedure: sphincterotomy plus stent placement for biliary leak (Figure 1) and progressive pneumatic dilatation, and double stent placement for stricture (Figure 2). Sphincterotomy alone for Oddi dysfunction, diagnosed as a lack of biliary and contrast flow through the papilla and dilatation of the choledochus (manometry of Oddi is nor available at our Institute, Figure 3); and finally, stone removal with Fogarty balloon or Dormia for stones. For cases requiring more than one procedure, ERCPs were repeated every 3 mo. ERCP was considered unsuccessful when biliary damage was not resolved despite an adequate endoscopic treatment: more precisely, when there was evidence of continuous bile leakage despite endoscopic stent placement, and/or persistence of stenosis, after 1 year, despite multiple dilatation and stent placement. When the endoscopic treatment failed, a percutaneous trans-hepatic approach (PTC) or surgery, with Roux-en-Y choledochojejunostomy, was adopted.

From June 2003 to June 2007, 261 adult patients were transplanted in our institute, 68 from living donors and 193 from cadaveric donors (2 were re-transplants after LRLTx failure). In the OLTx group with duct-to-duct anastomosis, 72/193 (37.3%) had biliary complications, while the rate in the LRLTx group was 44/68 (64.7%, Table 1). The follow-up was 22.18 ± 13.6 mo.

| OLTx (72/193) | LRLT (44/68) | |

| Stenosis | 55 | 20 |

| Leak | 5 | 12 |

| Stenosis + leak | 4 | 6 |

| Oddi dysfunction | 6 | 5 |

| Stenosis + stones | 1 | 1 |

| Biliary sludge | 1 | 0 |

| Time of onset (mo) | 5.1 (SD, 7.1) | 3.7 (SD, 3.97) |

The highest rate of complications, 78.6%, was observed during the first 6 mo after transplantation. Biliary leaks occurred in 9 (12% of all complications) patients: 5 with leak alone and 4 with an associated anastomotic stricture. All biliary leaks occurred at the anastomosis, and were diagnosed within 3 mo of transplant. Of the 5 patients with leaks alone, 2 recovered well after endoscopy (within 3 mo), 2 required PTC, and 1 is still in follow-up. Of the 4 patients with leaks and stenosis, 1 recovered after 3 ERCPs (6 mo), 1 needed percutaneous stent placement, and 2 are in follow-up.

Anastomotic stenosis occurred in 60 patients (80% of all complications): 4 of them with biliary leak and 1 with associated biliary stones. In 45/60 patients (75%) the diagnosis was done within 6 mo. Of the 55 patients with stenosis alone, 27 recovered well with endoscopic treatment within 1 year, while 2 recovered after 18 mo (success rate, 52.7%). Seventeen patients are still in follow-up. Eleven patients required further treatment: 10 required PTC (2 required subsequent surgery), while 1 patient was treated directly with surgical anastomosis reconstruction. The patient with biliary stenosis and stones recovered after a single ERCP with dilatation and stone removal. The patients with biliary stenosis and leak are described above.

One patient presented biliary sludge at 1 mo after transplant, which was solved with an ERCP session with sphincterotomy and stone removal.

Six patients had Oddi dysfunction after an average of 4 mo post-transplant. These patients were treated with sphincterotomy and recovered after one procedure. Three patients with high levels of cholestatic index and MRI positive for anastomosis stricture showed a normal cholangiography, so no therapy was undertaken.

Finally, in the OLTx group, we observed 14 ERCP failures (19.4%): 13 patients needed PTC with internal-external stent placement (2 of them required surgery), and 1 underwent surgical biliary anastomosis reconstruction. The mean follow-up was 23.3 mo (4-52 mo). During the follow-up, 1 patient was re-transplanted due to graft failure. Eight patients died during follow-up (Table 2).

| OLTx (n = 72) | LRLT (n = 44) | |

| Number of procedures | 3.2 (SD, 2.4) | 3.5 (SD, 2.9) |

| Success rate (%) | 80.56 | 61.37 |

| Mean follow-up (mo) | 23.34 (SD, 13.13) | 21.02 (SD, 14.10) |

| PTC | 13 | 15 |

| Surgery | 3 | 6 |

| RE-OLTX | 1 | 2 |

| Death | 8 | 8 |

The highest rate of complications (79%) was observed in the LRLTx group during the first 6 mo after transplant. Biliary leaks occurred in 18 patients (40.9% of all complications). In 6 patients the leak was associated with anastomotic stricture. All leakages were observed at anastomosis, and all were diagnosed within 2 mo of transplantation. With regard to the 12 patients with leak alone, 3 recovered with ERCP after 1 mo, 3 mo and 4 mo, respectively, (average of 2.3 procedures). Of the 8 patients who did not recover despite the endoscopic treatment, 7 were treated with PTC (3 required subsequent surgery), and one was directly treated surgically due a large leak. The last patient treated by ERCP is still in follow-up. Of the 6 patients with leak and anastomosis stenosis, 4 are still in follow-up, 1 recovered with percutaneous approach and 1 surgically. None of the patients in this subgroup recovered after ERCP.

Anastomotic stenosis occurred in 27 patients: 1 patient had associated stones. Six patients had associated leak (discussed above). Anastomotic strictures occurred in 61.3% of patients with biliary complications. Of the 20 patients with anastomotic stricture, 9 recovered with the endoscopic treatment alone after a mean of 3.4 procedures (45% success rate); 5 patients are still in follow-up; and 6 required a percutaneous approach. The patient with stenosis and stones did not recover despite 7 ERCPs, and was treated successfully with a percutaneous approach. Five patients had Oddi dysfunction and recovered after 1 ERCP with sphincterotomy.

Finally, in the LRLTx group we observed 17 patients in whom the ERCP failed (38.6%): 15 were treated with PTC (4 requiring subsequent surgical treatment), and 2 were sent directly to surgery after ERCP failure. The follow-up was 21.02 ± 14.10 mo, with a maximum of 59 mo and a minimum of 3 mo. During the follow-up, 2 patients underwent OLTx due to graft failure. Eight patients died (Table 2).

This report shows the results and follow-up of a large cohort of patients who developed biliary complications after liver transplantation (from both cadaveric and living donors) and were treated with ERCP. As previously reported, even in our transplant recipient population, biliary complications are very frequent. Moreover, complications occur more frequently in the LRLTx than in the OLTx recipients. The high rate observed in our OLTx group may be explained by the broad use of extended donor criteria (EDC) at our institute: 46.1% (89/193) of OLTx recipients received a marginal allograft. In the sub-group of patients receiving marginal livers the rate of biliary complications was higher (41.6%) than in non-marginal graft recipients (33.6%), though this difference was not statistically significant.

The extensive use of LFT and MRI for diagnosis of biliary disease results in a correct indication for ERCP: no false negative and 3 false positive (with normal cholangiography at ERCP) were observed. Most of the complications (about 80%) occurred within 6 mo of transplant (early complications); the most frequent was the anastomotic stricture, even if biliary leaks accounted for approximately 40% of all complications in the LRLTx group.

In this series, biliary complications were initially treated with a standard ERCP, using the conventional procedures: sphincterotomy with stent placement for biliary leak, and with progressive pneumatic dilatation, and double stents placement for stricture; sphincterotomy alone for Oddi dysfunction and stone removal with Fogarty balloon for stones. In the cases for which more than one session was required, the ERCPs were repeated every 3 mo (as maximum). The evidence of continuous bile leakage despite the endoscopic stent placement, or the persistence of stenosis after 1 year despite multiple dilatation and stent placement, was considered criteria for switching to another type of treatment: PTC as first choice, or surgery with biliary anastomosis reconstruction if the PTC approach failed or in the event of a very large leak. This approach led to a higher success rate in the OLTx group than in the LRLTx group: the ERCP was successful in 80.56% of the OLTx recipients, vs 61.37% for the LRLTx group. If we analyze the complications separately, the success rate for the treatment of anastomotic stenosis was the same in the both groups, but the success rate for the leak treatment was lower in the LRLTx group. The mean follow-up was long enough to allow us to view these data as reliable (22.18 ± 13.6 mo).

In conclusion, our data confirmed that, although ERCP is a quite effective mode of managing post-transplant bile duct complications, a significant number of patients need other types of approach. Therefore, different techniques should be considered in order to improve the results. For instance, large, fully-covered metallic stents could improve the results for biliary leakage, and, in patients with stenosis, reduce the number of dilatation sessions. Partially covered metal stents have been employed in an effort reduce stricture recurrence and to maintain duct patency; these stents are effective in the initial treatment of stricture but long term success is limited due to problems with stent patency[11]. The use of fully covered metal stents (removable) for leaks and strictures has not been tested yet, so further prospective studies are necessary in order to establish whether these new devices could improve the current results.

Biliary complications are the most frequent problem after liver transplantation. This rate of complications is higher for living-related liver transplantation (LRLTx) vs orthotopic liver transplantation (OLTx). Early diagnosis is crucial, as the treatment may improve graft function and help to avoid repeated surgery. Some studies have already been published on the endoscopic treatment of biliary complications and show a success rate of approximately 70%-80% of cases. But no standardized treatments in a long follow up were tested.

Although our data confirmed that Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopan-creatography (ERCP) is a quite effective mode of managing post-transplant bile duct complications in a long follow up, a significant number of patients need other types of approach. Therefore, different techniques should be considered in order to improve the results. Partially covered metal stents have been employed in an effort to reduce stricture recurrence in benign stenosis and to maintain duct patency, but these stents are effective only in the initial treatment of strictures and the long term success is limited due to problems with stent patency. For instance, large, fully-covered metallic stents (removable) could improve the results for biliary leakage, and in patients with stenosis, reduce the number of dilatation sessions. The use of fully covered metal stents for leaks and strictures has not been tested yet, so in our opinion further prospective studies are required in order to establish whether these new devices, could improve the current results.

This is a large prospective study on transplanted patients (both from cadaveric and live donors), in which the endoscopic treatments and the criteria of endoscopic therapy failure were well defined and standardized. The mean follow-up is long enough to allow us to view these data as reliable.

Management of patients who underwent liver transplant from cadaveric and living donors, with duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis, who develop biliary complications.

This paper shows the long term results of a large cohort of patients treated with a well standardized endoscopic therapy; it clearly defines the criteria of endoscopic treatment failure with the appropriate timing to shift for other techniques. The long follow up allows the readers to consider the consistency of the results.

| 1. | Thuluvath PJ, Pfau PR, Kimmey MB, Ginsberg GG. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: the role of endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:857-863. |

| 2. | Bentabak K, Graba A, Boudjema K, Griene B, Debzi N, Bekkouche N, Yahiatene S, Fellah N, Benmoussa D, Faraoun SA. Adult-to-adult living related liver transplantation: preliminary results of the Hepatic Transplantation Group in Algiers. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2873-2874. |

| 3. | Thuluvath PJ, Atassi T, Lee J. An endoscopic approach to biliary complications following orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2003;23:156-162. |

| 4. | Ludwig J, Batts KP, MacCarty RL. Ischemic cholangitis in hepatic allografts. Mayo Clin Proc. 1992;67:519-526. |

| 5. | Campbell WL, Sheng R, Zajko AB, Abu-Elmagd K, Demetris AJ. Intrahepatic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Radiology. 1994;191:735-740. |

| 6. | Boraschi P, Braccini G, Gigoni R, Sartoni G, Neri E, Filipponi F, Mosca F, Bartolozzi C. Detection of biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation with MR cholangiography. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;19:1097-1105. |

| 7. | Stratta RJ, Wood RP, Langnas AN, Hollins RR, Bruder KJ, Donovan JP, Burnett DA, Lieberman RP, Lund GB, Pillen TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Surgery. 1989;106:675-683; discussion 683-684. |

| 8. | Greif F, Bronsther OL, Van Thiel DH, Casavilla A, Iwatsuki S, Tzakis A, Todo S, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. The incidence, timing, and management of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 1994;219:40-45. |

| 9. | Pfau PR, Kochman ML, Lewis JD, Long WB, Lucey MR, Olthoff K, Shaked A, Ginsberg GG. Endoscopic management of postoperative biliary complications in orthotopic liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:55-63. |

| 10. | Khuroo MS, Al Ashgar H, Khuroo NS, Khan MQ, Khalaf HA, Al-Sebayel M, El Din Hassan MG. Biliary disease after liver transplantation: the experience of the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:217-228. |

| 11. | Judah JR, Draganov PV. Endoscopic therapy of benign biliary strictures. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3531-3539. |