Published online Jun 14, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3594

Revised: April 30, 2008

Accepted: May 7, 2008

Published online: June 14, 2008

Ascites is not an uncommon manifestation of certain solid tumors like gastrointestinal malignancies, ovarian cancer and breast cancer. However, it is unusual to encounter ascites in patients with hematological malignancies especially chronic leukemia. The patient described here presented with massive ascites and blood lymphocytosis. Further studies confirmed the diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with ascites. The ascitic fluid was exudative, consisting of mature-looking B-lymphocytes, which were morphologically and immunophenotypically similar to peripheral blood and bone marrow cells. The patient was treated with chemotherapy and achieved a good response and diminution of ascitic fluid accumulation.

- Citation: Siddiqui N, Al-Amoudi S, Aleem A, Arafah M, Al-Gwaiz L. Massive ascites as a presenting manifestation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(22): 3594-3597

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i22/3594.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.3594

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most common hematological malignancy in the elderly. The disease is often indolent or slowly progressive. Approximately 40% of the patients are asymptomatic in the initial stages and the diagnosis is first made on the basis of a complete blood count when more than 5 × 109/L lymphocytes are found on differential white cell count and confirmed by a characteristic immunophenotyping pattern of peripheral blood or bone marrow lymphocytes. The common clinical features of the disease are lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, malaise and weight loss. Bacterial infections, most often pneumonias, are fairly common in these patients. Less common complications are infiltration of various organs and transformation of the leukemia into other hematological malignancies. Ascites, however, is very rare in CLL patients particularly at the time of initial diagnosis. Development of ascites in CLL has been described at the time of relapse or transformation into prolymphocytic leukemia or Richter’s syndrome[1–3]. It was only once reported as an initial manifestation of the disease and also as a case of chylous ascites[4].

A 75-year-old man was referred to our institute in March 2004 because of progressively increasing abdominal distension over a four-month period. More recently, he had also noticed weight loss, fatigue and night sweats. There was no history of change in bowel or bladder function, use of tobacco or alcohol. There was no history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension or heart disease. He had never required hospitalization prior to this admission.

Physical examination revealed an elderly man in obvious discomfort due to abdominal distension. He had generalized symmetrical lymphadenopathy including bilateral cervical, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes. There was minimal peripheral edema. His abdomen was protuberant with bulging flanks and a positive fluid thrill. There was no hepatosplenomegaly and no stigmata of chronic liver disease.

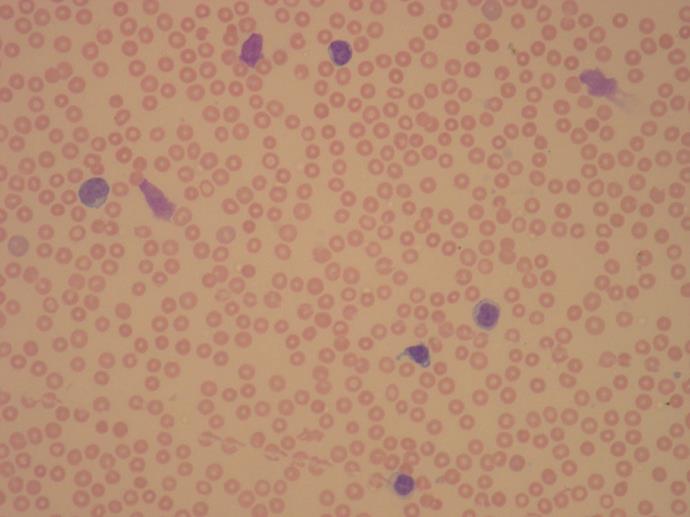

On admission, his complete blood count revealed a white blood cell count of 45.2 × 109/L, hemoglobin of 119 g/L, and platelet count of 62 × 109/L. The absolute lymphocyte count was 33 × 109/L. Peripheral blood smear examination showed lymphocytosis with mature lymphocytes and many smear cells (Figure 1). The lymphocytes were of variable small to medium size and most revealed round nuclei with some displaying nuclear irregularity. Prolymphocytes were only 8%. Flow cytometry performed on the peripheral blood showed the lymphocytes to be positive for CD5, CD19, CD20, CD23 and FMC7 and negative for CD10 and CD7. Bone marrow examination showed diffuse infiltration of the marrow with around 95% of the cells being lymphocytes. Many smear cells were seen. Normal hematopoiesis was markedly reduced. Cytogenetic studies did not reveal any chromosomal abnormalities. Serum protein electrophoresis disclosed low total protein with a normal percentage of albumin (56%). Serum immunoelectrophoresis revealed a decrease in both the serum IgG level (6.88 g/L; normal, 8-18) and IgM level (0.30 g/L; normal, 0.6-2.5).

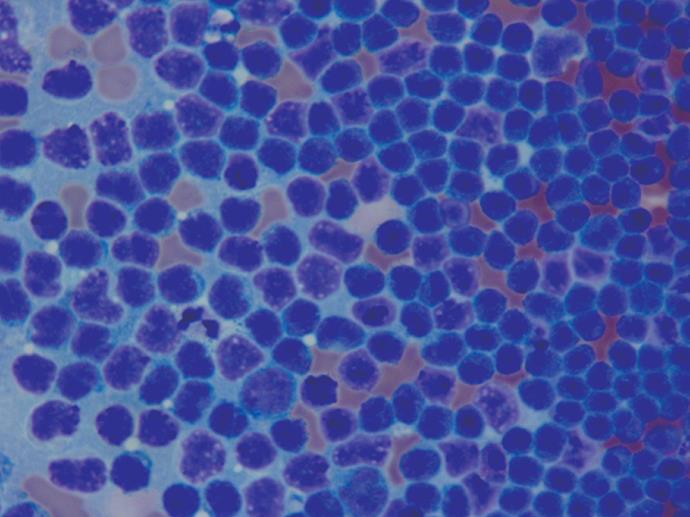

His electrocardiogram was normal and a chest X-ray showed mediastinal lymphadenopathy. CT scan of the thorax and abdomen disclosed multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the axilla, mediastinum, abdomen and inguinal region. There was gross ascites with edema of the abdominal wall. Liver, spleen and the peritoneum appeared normal with no evidence of portal hypertension. At this stage, two liters of clear yellowish ascitic fluid was removed for symptomatic relief and laboratory analysis. Biochemistry of the ascitic fluid revealed the total protein was high, 13 g/L, and glucose and lactate dehydrogenase were normal. Thus, the fluid was exudative with a low serum ascitic albumin gradient. On microscopic evaluation, it was a highly cellular specimen consisting of numerous non-cohesive, small monomorphic lymphoid cells containing hyperchromatic nuclei with coarsely granular chromatin and mesothelial cells seen in the background (Figure 2). Morphological picture and immunophenotyping by flow cytometry of the ascitic fluid were consistent with small lymphocytic lymphoma/leukemia cells similar to blood and bone marrow. The gram-staining, culture and acid fast bacilli were negative.

Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies were performed to rule out a coexisting gastrointestinal malignancy as a cause of ascites. The endoscopic findings along with serum α-fetoprotein were normal. Hepatitis B and C studies were negative.

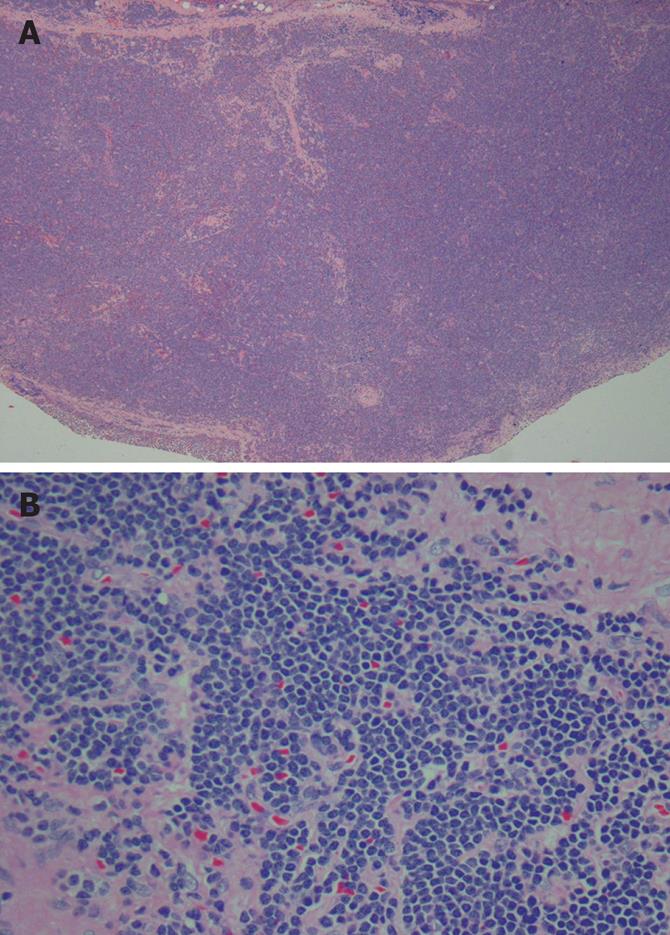

The lymph node biopsy showed total nodal efface-ment, with perinodal tumor infiltration and diffuse proliferation of small lymphoid cells (Figure 3). These cells were small and round with minimal degree of nuclear irregularity and scant cytoplasm. Several proliferating centers containing paraimmunoblasts were also present. These paraimmunoblasts were larger in size than the background lymphocytes having round nuclei with a vesicular chromatic pattern and medium to large nucleoli. These were found in aggregates that appeared pale and scattered in between the small lymphocytes.

Based on CD5/CD19 positive lymphocytosis, lymphadenopathy and thrombocytopenia, a diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Rai stage V was made[5]. It was interesting to notice that the peripheral blood, bone marrow and ascitic fluid studies showed a clonal proliferation of mature lymphocytes.

In view of the above diagnosis, the patient was commenced on cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisolone (CVP) chemotherapy. He received three cycles of chemotherapy with a good response. His blood count normalized with disappearance of the lymph nodes and there was a remarkable reduction in the rate of accumulation of ascites. Unfortunately, after the third cycle of therapy, the patient failed to attend the oncology clinic (having had to travel more than 1000 kilometers on each occasion) and was lost to follow-up.

In 1982, May and Costanzi reported a known case of CLL whose relapse was heralded by development of splenomegaly with massive ascites[6]. The ascitic fluid was a transudate with polymorphonuclear leukocytes and mononuclear cells. On cytopathology, there were no lymphocytes or abnormal cells. They attributed the cause of ascites to be periportal infiltration of the liver and marked infiltration of the spleen leading to portal hypertension. A similar case of portal hypertension caused by intra-hepatic block in CLL was later reported by Mouly[7].

Clonal evolution is common in CLL during the course of the disease. This disease may convert to prolymphocytic leukemia, diffuse large-cell lymphoma or acute leukemia. “Prolymphocytoid” transformation of CLL is characterized by appearance of increasing number of large cells with irregular nuclei, i.e., prolymphocytes and development of hepatosplenomegaly. Ascites and pleural effusion have occasionally been described in this setting[2]. The ascitic fluid consists of prolymphocytes and is an exudate with low albumin gradient. Our patient had a very small population of prolymphocytes in the peripheral blood and none in the ascitic fluid, therefore transformation of CLL to “prolymphocytic leukemia” was not considered.

About 3%-10% cases of CLL may transform to diffuse large-cell lymphoma when it is called “Richter’s syndrome”. This is usually a terminal event with very poor prognosis. A few cases of ascites developing at the time of Richter’s transformation have been described in the literature[389]. The ascitic fluid in these cases showed large blast-like lymphoma cells similar to the cells in the lymph node biopsy. In our patient, the ascitic fluid consisted of mostly small mature-looking lymphocytes consistent with CLL and not diffuses large cell lymphoma or acute leukemia.

Other possible causes of ascites which could be related to CLL are infection leading to subacute bacterial peritonitis, another malignancy or portal hypertension. Although patients with CLL are at high risk of infection, in this patient there was no evidence of a specific organism causing bacterial peritonitis, nor was there any indication of tuberculous peritonitis. There have been some reports of increased incidence of second solid tumors in patients with CLL. Carcinoma of gastrointestinal tract and lung were ruled out in our patient by normal results of endoscopies and CT scans. Since serum α-fetoprotein was normal and there was no hepatic lesion on CT, hepatocellular carcinoma was also unlikely as a cause of ascites in this patient. The remaining differential diagnosis in this patient may be hepatic cirrhosis, heart failure, or renal disease. However, all of these possibilities were systematically screened and excluded.

In conclusion, the patient described here had an unusual presentation of CLL. The ascitic fluid consisted of mature B-cell type lymphocytes, morphologically and immunophenotypically similar to the peripheral blood and bone marrow cells. The mechanism of ascites in this case can only be speculated. It is possible that despite the normal radiological studies, there may be microscopic peritoneal deposition by leukemia cells or portal system lymphatic obstruction due to extensive lymphatic infiltration. The fact that the ascitic fluid was sterile and most of the cells were mature lymphocytes, like in the blood, suggests that the ascites in this patient was due to infiltration of the peritoneum and was malignant ascites not significantly different from that found in solid tumors. A liver biopsy in this case might have been helpful in confirming a normal histology but it was not done as it was not indicated in the opinion of the managing team. It is interesting to note that there was a good response to chemotherapy with marked reduction in ascites. Unfortunately, nothing further can be commented in this regard because of the lack of follow-up after three cycles of chemotherapy. In view of the continued increase in the number of cases diagnosed with CLL, a greater awareness of the possibility of development of ascites as a presenting manifestation of this disease may be beneficial to the physicians caring for patients with ascites.

| 1. | Mamode C, Beauregard P, Langevin S, Mongeau CJ. [Chronic lymphoid leukemia complicated with ascites]. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14 Suppl D:181D-184D. |

| 2. | Shimoni A, Shvidel L, Shtalrid M, Klepfish A, Berrebi A. Prolymphocytic transformation of B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia presenting as malignant ascites and pleural effusion. Am J Hematol. 1998;59:316-318. |

| 3. | Cuneo A, de Angeli C, Roberti MG, Piva N, Bigoni R, Gandini D, Rigolin GM, Moretti S, Cavazzini P, del Senno L. Richter's syndrome in a case of atypical chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with the t(11;14)(q13;q32): role for a p53 exon 7 gene mutation. Br J Haematol. 1996;92:375-381. |

| 4. | Davis MN, Alloy AM, Chiesa JC, Pecora AA. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia presenting with massive chylous ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:593-596. |

| 5. | Rai KR, Sawitsky A, Cronkite EP, Chanana AD, Levy RN, Pasternack BS. Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1975;46:219-234. |

| 6. | May JT, Costanzi JJ. Ascites in chronic leukemia: a case report and review of the literature. Oncology. 1982;39:55-58. |

| 7. | Mouly S, Cochand-Priollet B, Halimi C, Bergmann JF. [Portal hypertension caused by intra-hepatic block in chronic lymphoid leukemia]. Presse Med. 1996;25:497-498. |

| 8. | Desablens B, Gineston JL, Joly JP, Piprot-Choffat C, Sevestre H, Capron JP. [Immunoblastic lymphoma of the ileocecal region in chronic lymphoid leukemia. Richter's syndrome localized in the intestine and disclosed by ascites]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1987;11:901-903. |

| 9. | Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 31-1983. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia with the recent development of hepatosplenomegaly and ascites. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:297-305. |