INTRODUCTION

Diving is a difficult underwater activity in which environmental conditions can affect body structure and function. Barotrauma is caused by compression during descent or expansion during ascent, of the gas filled spaces of the body and it may be associated with pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum and embolism. Decompression sickness may occur when gas, which has dissolved in tissues at depth, eventually produces bubbles which occasionally result in severe cardiorespiratory and neurological emergencies[1].

Approximately 13% of divers complain of gastrointestinal disturbances upon ascent, while most of them present as aerophagy[2]. Rarer, more severe diving-associated gastrointestinal manifestations have been reported in the literature, including a few cases of gastrointestinal barotraumas, mainly gastric rupture[3–6] and a case of small bowel infarction due to thrombosis of mesenteric veins[7]. We describe a clinical case of ischemic colitis in a 27-year-old male admitted to our emergency department, who manifested abdominal pain while he was in the process of scuba diving 20 meters undersea, followed by bloody diarrhoea as soon as he ascended to sea level. Taking into account his past medical history, the thorough impeccable clinical and laboratory examinations and presence of no other factors predisposing to ischemia of the colon, we assume that a possible relationship between the diving conditions and the pathogenesis of ischemic colitis may exist. This case, is as far as we know, the first report relating scuba diving with acute ischemic colitis.

CASE REPORT

A 27-year-old male novice scuba diver came to the emergency department of our hospital, accompanied by his father, suffering from lower abdominal pain with concurrent bloody diarrhoea. He reported that 2 h earlier, he was submerged for approximately 5 min at a depth of 20 meters when he experienced an acute and intense lower abdominal pain with a simultaneous urge to defecate. Further, he insisted that although under stress, his ascent had been completely normal, under control and in accordance with a scheduled dive plan. Immediately after reaching the surface, he had two loose bowel movements followed by bloody diarrhoea and tenesmus. Our patient was a non-smoker, was taking no medication, and his past medical history was limited to a known Gilbert’s syndrome. When admitted to the accident and emergency department his vital signs were: blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg, pulse rate of 72 bpm and respiratory rate of approximately 12 breaths/min. Physical examination revealed a moderate abdominal tenderness at the left lower quadrant and a mild abdominal distention, while per rectum examination confirmed the presence of fresh blood in the lumen with no other apparent physical signs of clinical importance detected.

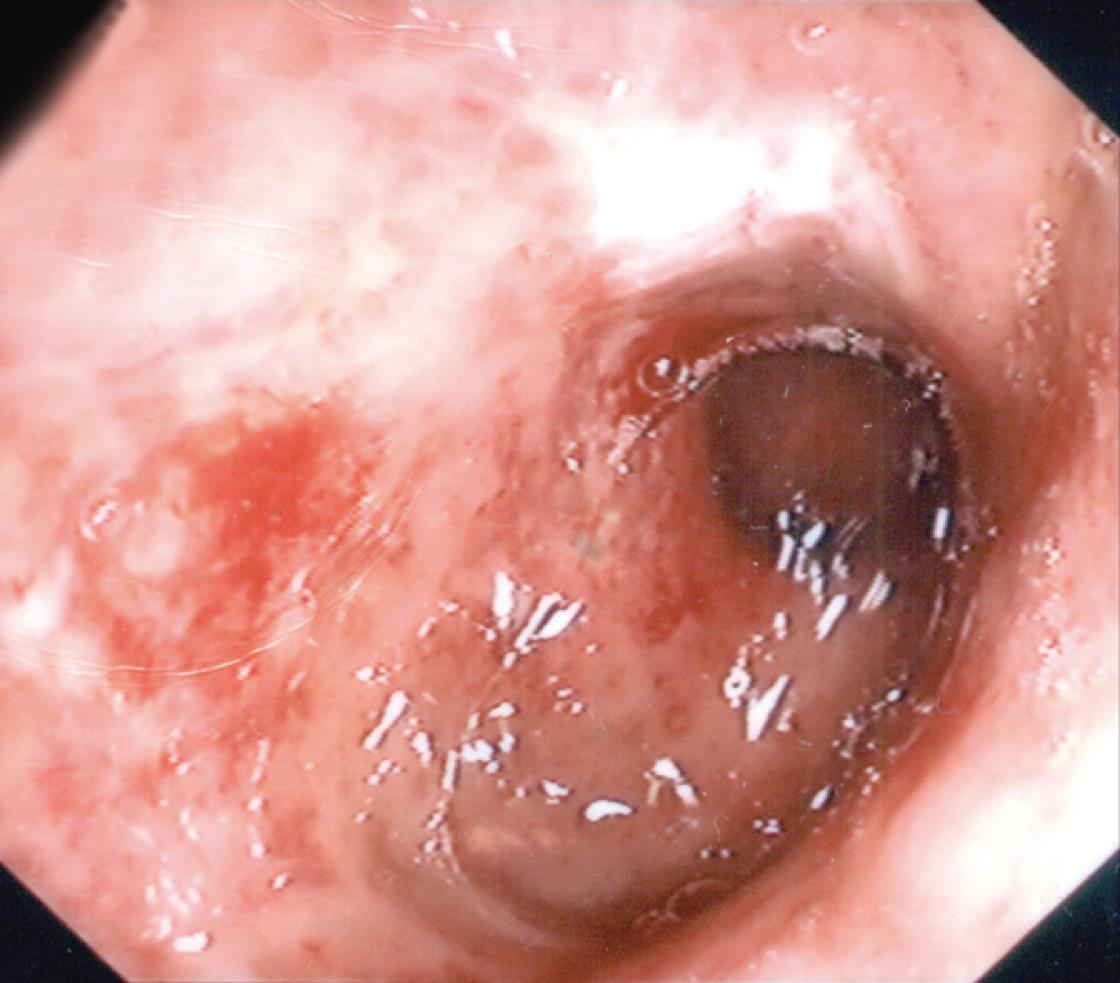

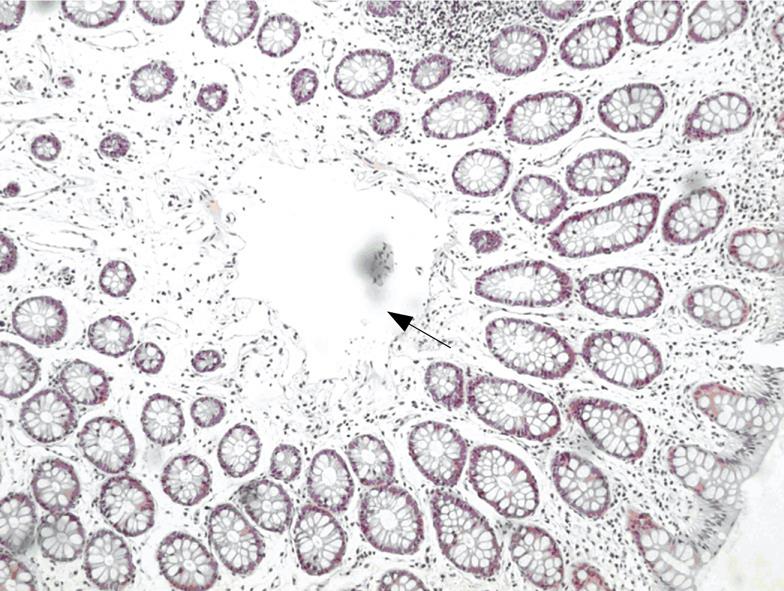

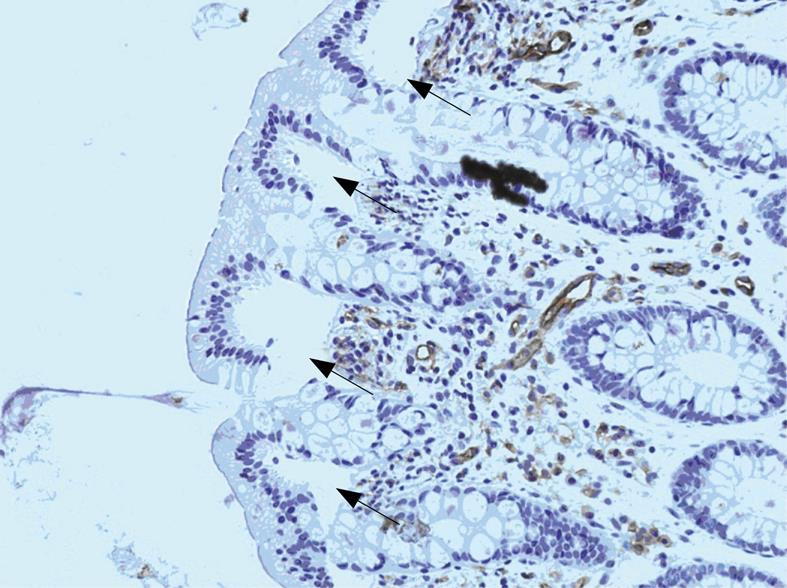

Laboratory results were: Hematocrit (HCT): 47.1%, white cell counts (WCC): 7.800/&mgr;L with 63% neutrophils, 27% lymphocytes, 7% monocytes and 3% eosinophils, platelet (PLT): 236.000/&mgr;L, total-bilirubin: 2.73 mg/dL, Direct-bilirubin: 0.25 mg/dL and serum lactic dehydrogenase: 223 U/L. Coagulation tests including prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), fibrinogen, protein S, protein C, antithrombin III and V leiden factor were in the normal range. Urea and electrolytes, antiphospholipid antibodies, serum amylase, blood gases and all other tests including urine analysis were also normal. Chest and abdominal X-rays plus ultrasound examination of both upper and lower abdomen did not reveal any pathological findings. Colonoscopy, with inspection of the terminal ileum, performed 24 h later, revealed an edematous mucosa of the sigmoid colon in extent of 20 cm, with redness, superficial ulcerations and submucosal haemorrhages (Figure 1). The histological study of specimens taken from the affected area showed findings compatible with ischemic colitis, while the pathologist noticed presence of air in the lamina propria but not intravascularly (Figures 2 and 3). No air was detected in the colon wall by magnetic resonance tomography performed 2 d after admission.

Figure 1 Endoscopic image of patient’s ischemic colitis.

Figure 2 ΗΕ staining of colonic mucosa with an air bubble in the lamina propria (arrow).

Figure 3 Immunohistochemistry for CD31 revealing lack of staining in the areas of air bubbles in the lamina propria (arrows).

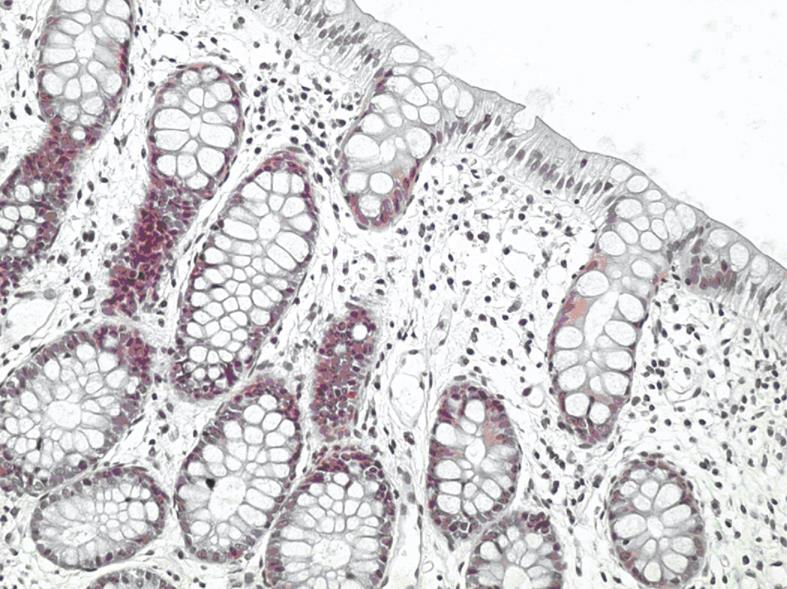

The patient recovered uneventfully with bloody diarrhoea ceasing a few hours after admission and abdominal pain progressively diminishing till disappearance in 48 h. The patient was discharged with complete comeback 4 d after admission. The follow-up colonoscopy two mo later showed complete endoscopic and histologic healing of the mucosa (Figure 4) with the patient free of any clinical symptoms.

Figure 4 HE staining of normal histologic appearance of our patient’s colonic mucosa, 2 mo after the ischemic colitis episode.

DISCUSSION

Abdominal discomfort and belching due to air swallowing are quite frequent manifestations during diving, with more severe gastrointestinal complications scarcely described. Gastric rupture due to expansion of intra-gastric air during a quick ascent to sea level has been described in a few case reports[3–6]. Massive pneumoperitoneum without rupture of an abdominal hollow viscous organ, possibly caused by lung barotrauma has also been reported[8]. Gertler et al have presented a case of mesenteric vein thrombosis as a unique complication of decompression sickness[7]. Finally, we must emphasize that a confirmed case of acute ischemic colitis in association with scuba diving has never been reported.

In our case, the patient’s clinical manifestations of ischemic colitis initiated with acute abdominal pain while at a depth of 20 meters under sea, progressing to bloody diarrhoea on the surface. Several environmental parameters during diving can alter body function and structure[1], as for approximately every 10 meters of descent in sea water ambient pressure increases by 100 kPa (1 bar). The air trapped in body cavities including the gastrointestinal tract, is therefore subjected to compression during descent and expansion during ascent to sea level, which may lead to tissue damage such as gastric rupture[3–6]. Decompression sickness occurs when the partial pressure of gas trapped in the hollow cavities of the body raises in direct proportion to the increase in ambient pressure. This leads to large volumes of inert gas, mainly nitrogen, which dissolve in tissues while at depth transforming to bubbles during ascent to sea level. In addition breathing workload increases due to a combination of increased gas density, increased hydrostatic pressure and altered respiratory mechanisms. Finally, a number of unpredictable events such as malfunction of a diving equipment or technical issues, as well as panic attacks or hypothermia of the diver, may increase the existing physical and/or psychological stress. In our case, except for the arduous and stress inducing conditions during underwater activity, other factors predisposing to ischemic colitis were not identified.

Our patient’s past medical history was free of thrombotic events whilst complete examination and evaluation of the patient, including specific blood tests, did not reveal any type of coagulopathy. On the other hand, the pathophysiologic mechanism of decompression sickness could predispose to vascular obstruction and venous infarction[9]. The partial pressure of body gases increases during a scuba dive, resulting in a time-dependent concentration of mainly nitrogen in body fluids and tissues. Bubbles can be formed during ascent due to rapid decrease of barometric pressure. Bubbles are formed predominately in the venous circulation, although in overwhelming decompression sickness they can be found in the arterial circulation also[10], causing vascular obstruction due to coalition. Although bubble formation is considered as the causative mechanism of decompression sickness, a series of heamatological disorders leading to a hypercoagulable state have been described[911]. In vitro experiments concluded that increased vascular permeability, vascular obstruction due to fat emboli and interaction of the bubble surface with the cellular elements of the blood, may contribute to the pathogenesis of decompression sickness[912]. Mesenteric vein thrombosis[7], retinal artery occlusion[13] and vascular obstruction due to fat emboli[14], have previously been reported as unique complications of decompression sickness. The presence of trapped air in the lamina propria, likely of intravascular origin, demonstrated in biopsies taken from the colonic area with ischemic lesions, supports the thesis that decompression sickness was the main cause of our patient’s colonic ischemia. Vascular bubbles and bowel wall congestion are the visceral changes described in decompression sickness[15]. It has recently been reported that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be superior to autopsy in the demonstration of gas in intraparenchymal blood vessels of internal organs[16]. Our patient’s MRI scan didn’t reveal any intravascular air bubbles, which can be attributed to the 48 h delay between the scan and the onset of the acute episode. Finally, a procedure that may lead to rapid alleviation of decompression sickness symptoms[368] is recompression, which in our case was not implemented due to the rapid clinical improvement and complete recovery of the patient.

In conclusion, this unusual case emphasizes the probability that scuba diving can cause colonic ischemia, even in young patients with no known coagulation disorders or other factors predisposing to colonic ischemia.

Peer reviewer: Luis Rodrigo, Professor, Gastroenterology Service, Hospital Central de Asturias, c/Celestino Villamil, s.n., Oviedo 33.006, Spain