Published online Jan 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.85

Revised: October 8, 2007

Published online: January 7, 2008

AIM: To explore if C-reactive protein (CRP) levels might serve as a prognostic factor with respect to the clinical course of Crohn’s disease and might be useful for classification.

METHODS: In this retrospective cohort study we enrolled 94 patients from the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) database of the University Medical Centre Utrecht. CRP levels during relapse were correlated with the number of relapses per year. Severity of relapses was based on endoscopic reports and prednisone use. Furthermore, patients were categorized in a low or high CRP group based on their CRP response during relapse and demographic and clinical features were compared.

RESULTS: Overall, a positive correlation between CRP levels, number of relapses, and severity of relapse was found (respectively rs = 0.31, P < 0.01 and rs = 0.50, P < 0.001). Employing a cut-off level of 15 mg/L, the index CRP level was found to discriminate patients with respect to the number of relapses per year, as well as for severity of relapses (respectively 0.25 ± 0.16 vs 0.36 ± 0.24, P < 0.05 and 4.4 ± 1.2 vs 3.2 ± 1.1 on a 10-point visual analogue scale, P < 0.001 for the high CRP and low CRP groups respectively). In addition, the high CRP group showed more cumulative days of prednisone use per year (107 ± 95 vs 58 ± 48, P < 0.05), as well as a better response to infliximab (93 % vs 33 %, P = 0.06).

CONCLUSION: A higher CRP level during relapse seems to be associated with a more severe clinical course of disease.

- Citation: Koelewijn CL, Schwartz MP, Samsom M, Oldenburg B. C-reactive protein levels during a relapse of Crohn’s disease are associated with the clinical course of the disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(1): 85-89

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i1/85.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.85

Crohn’s disease (CD) is thought to result from an ongoing activation of the mucosal immune system leading to an inappropriate innate immune response to normal luminal factors in a genetically susceptible individual[12]. The clinical expression of CD is heterogeneous with a wide spectrum of patterns and different clinical courses. Classification of CD is, therefore, difficult[3]. In the Vienna Classification, distinct definitions to categorize patients with CD have been formulated[4]. This classification distinguishes between age (< or > 40 years), anatomical localization (terminal ileum, colon, ileocolon, upper gastrointestinal) and disease behaviour (non-stricturing/non-penetrating, stricturing and penetrating). However, it has been shown to be unreliable in predicting the course of the disease[56]. Currently, it is not known whether other tools, such as the recently developed Montreal classification will prove to be superior in this respect[78].

C-reactive protein (CRP), an acute phaseprotein produced by hepatocytes upon activation by proinflam-matory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1α and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is widely used as a parameter of inflammatory activity in a variety of infectious and inflammatory diseases[9–11]. Moreover, it has been found to correlate with clinical parameters of disease activity in CD[12–18].

We hypothesized that a high serum CRP level during a relapse predisposes patients to a more severe course of the disease. In the present study, we studied retrospectively the putative association between the height of CRP levels during a relapse and the clinical course of disease in patients with CD.

In this retrospective cohort study, 94 patients with CD were selected from the IBD database of the University Medical Centre Utrecht, comprising the records of all patients diagnosed with IBD in the period 1994-2005. CD patients were eligible if they were 18 years of age or older, had experienced at least one well-documented relapse during which serum CRP values were determined, and from whom records over a period of at least 4 years of follow-up were available. Excluded were patients with other chronic inflammatory diseases, concomitant infections or other serious comorbidity.

Data were collected from electronic and clinical charts. The index CRP level used for analysis had to be measured during a relapse which was confirmed by (ileo) colonoscopy and/or a small bowel follow-through examination. The highest CRP level during this exacerbation, within the first 4 wk after the onset of symptoms, was taken as an index CRP level. Severity of the index exacerbation was assessed retrospectively by two independent, blinded reviewers based on the endoscopic reports and recorded on a 10-point visual analogue scale (VAS). The mean of both scores was used for analysis.

The total number of relapses during follow up was assessed. These relapses were defined as a period of inflammatory activity accompanied by progressive symptomatology which was confirmed by (ileo) colonoscopy and/or a small bowel follow-through examin-ation and requiring hospitalization and/or initiation of treatment with steroids or other immunosuppressive drugs. Another primary endpoint was the use of prednisone, measured in number of days during follow up.

Furthermore, age at the time of the diagnosis of CD, duration of the disease, localization and behaviour of CD according to the Vienna Classification, the presence of granulomas in pathology specimens, smoking behaviour, surgical treatment and treatment with immunosuppressives other than prednisone (azathioprine, mesalazine, methotrexate, budesonide, cortisone enema’s or infliximab) were noted.

Analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, version 12.0. The correlation between the index CRP value and the primary outcome measures were calculated employing a bivariate correlation with a non-parametric distribution (Spearman’s rho). Differences in the primary, as well as the secondary outcomes of the Low C-reactive protein subgroup (LCRP) and High C-reactive protein subgroup (HCRP) groups were calculated with the Mann Whitney U test to compare means (non-parametric distribution) and the chi-square test to compare the differences in distribution (non-parametric distribution).

All tests were 2-tailed analysed. Data are presented in mean ± SD or otherwise stated. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

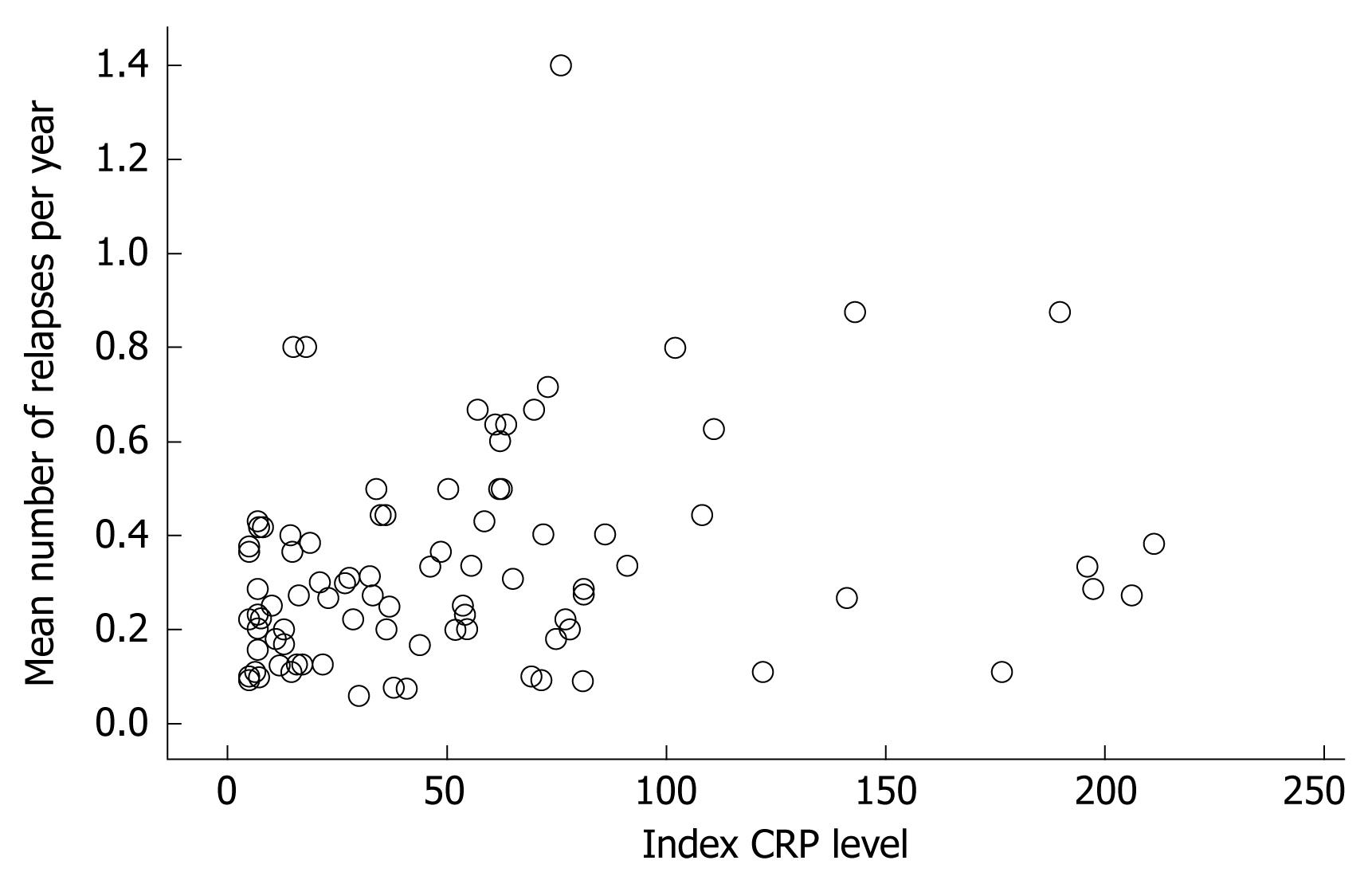

For the whole group, a significant positive correlation between the index CRP level and the number of relapses per year was noted (rs = 0.31, P < 0.01, Figure 1). Severity of relapses was correlated with the index CRP level as well (rs = 0.50, P < 0.001). The severity was based on the mean score of both independent reviewers with an interobserver correlation of rs = 0.71, P < 0.001. The correlation between the index CRP level and cumulative use of prednisone per year was small but significant, rs = 0.22, P < 0.05.

Based on the index CRP levels two groups were created, the LCRP and HCRP group, with a cut-off level of 15 mg/L. Twenty-seven patients had a serum CRP level of ≤ 15 mg/L and 67 had a CRP level of > 15 mg/L. Baseline characteristics of the subgroups are given in Table 1. The baseline characteristics of the groups were similar. There were no differences between the two groups regarding gender distribution, mean age, age at the time of diagnosis, disease localization and disease behaviour according to the Vienna classification.

| Index serum CRP level during relapse (mg/L) | ≤15 | > 15 | P-value |

| LCRP | HCRP | ||

| n | 27 | 67 | |

| Time of follow-up, yr (SD) | 10.8 (4.0) | 10.3 (3.7) | NS |

| Demographic factors | |||

| Sex: men | 12 (44.4%) | 32 (47.7%) | NS |

| Mean age, yr (SD) | 45 (13.5) | 42 (11.0) | NS |

| Clinical features | |||

| Age at time of diagnosis (SD) | 27.0 (8.3) | 27.4 (10.8) | NS |

| Duration of disease, yr (SD) | 18.0 (10.2) | 14.3 (7.3) | NS |

| Localization | |||

| Terminal ileum | 6 (22.2%) | 8 (11.9%) | NS |

| Colon | 7 ( 25.9%) | 31 (46.2%) | |

| Ileocolon | 13 (48.1%) | 26 (38.8%) | |

| Upper gastrointestinal | 1 (3.7%) | 2 (3.0%) | |

| Behaviour | |||

| Non-stricturing non penetrating | 13 (48.1%) | 26 (38.8%) | NS |

| Stricturing | 7 (25.9%) | 15 (22.4%) | |

| Penetrating | 7 (25.9%) | 26 (38.8%) |

Table 2 shows the clinical findings, drug use, surgeries and related factors in the two groups. The numbers of relapses were respectively 0.25 ± 0.16 and 0.36 ± 0.24 per year in the LCRP and HCRP group (P < 0.05). The mean severity of the index exacerbation on a 10-point VAS was 4.4 ± 1.2 in the HCRP and 3.2 ± 1.1 in the LCRP group (P < 0.001). The number of courses of prednisone did not differ between the groups, but patients in the HCRP group were treated significantly longer with prednisone than LCRP-patients, 107 ± 95 vs 58 ± 48 d per year (P < 0.05).

| Index serum CRP level during relapse (mg/L) | ≤15 | > 15 | P-value |

| LCRP | HCRP | ||

| Clinical findings | |||

| Mean number of relapses per year (SD) | 0.25 (0.16) | 0.36 (0.24) | < 0.05 |

| Mean severity of the index relapse according to endoscopic reports, on a 10 points visual analogue scale (SD) | 3.18 (1.09) | 4.39 (1.24) | < 0.001 |

| Drug use | |||

| Number of patients with prednisone use | 23 (85.2%) | 62 (92.5%) | NS |

| Mean number of days of prednisone use per year (SD)1 | 58 (48) | 107 (95) | < 0.05 |

| Surgeries | |||

| Number of patients who underwent ≥ 1 surgeries | 12 (44.4%) | 27 (37.3) | NS |

| Total number of surgeries23 | 2.0 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.09) | NS |

| Related factors | |||

| Smoking: n | 23 | 58 | |

| smokers | 8 (34.8%) | 24 (41.4%) | NS |

| non-smokers | 11 (47.8%) | 24 (41.4%) | |

| quitted smokers | 4 (17.4%) | 10 (17.2%) | |

| Presence of granulomas: n | 22 | 51 | |

| 8 (36.4%) | 25 (49.0%) | NS |

There was no significant difference in the number of patients on infliximab in both groups, 20.9 % in the HCRP and 11.1% in the LCRP group, but the response rate was higher in the HCRP subgroup compared to the LCRP subgroup, respectively 92.8% vs 33.3%, P = 0.06.

In the follow-up of patients in the HCRP and LCRP groups, the percentages of azathioprine (77.6 vs 66.7), mesalazine (98.5 vs 100), budesonide (71.6 vs 63.0), cortisone enema’s (43.3 vs 44.4) and methotrexate (4.5 vs 3.7) use did not differ significantly, nor did the total number of CD-related surgeries [1.7 (SD 0.1) vs 2.0 (SD 0.6) per patient], construction of stomas (22.4 % vs 22.2 %) or development of fistulas and/or abscesses (26.9 % vs 18.5%).

There were no significant differences between smokers and non-smokers. Patients with granulomas were significantly younger (38.4 ± 8.5 vs 45.4 ± 13.3 years, P < 0.05) and tended to be younger at the time of diagnosis (24.2 ± 5.9 vs 29.7 ± 12.1 years, P = 0.09) compared with patients without granulomas. Other differences were not detected.

We hypothesized that the CRP response during a relapse of CD discriminates between phenotypic subsets of patients with an aggressive or more benign course of disease and predicts the response to drugs. We found a significant but relatively modest correlation between level of CRP during the index exacerbation and the number, as well as the severity of relapses per year. A significant, but rather small, correlation between CRP level and prednisone use was revealed. LCRP and HCRP groups were found to be comparable regarding baseline characteristics but the number and severity of relapses was significantly higher in HCRP patients. Furthermore, patients in the HCRP group appeared to respond better to infliximab infusions. The latter phenomenon is in line with literature. This apparently more aggressive disease behaviour in the HCRP patients was not reflected in a higher frequency of drug use other than prednisone. A possible explanation is the tertiary referral setting of this study, resulting in enrolment of relative severe cases of CD in most of whom immunomodulators were already prescribed.

Interestingly, we found the index CRP and severity of relapse based on endoscopic reports to be correlated. CRP levels are found to be weakly associated with clinical activity indices by several authors[1419–21], although this has not been reported consistently[22]. Colombel et al reported a striking correlation of CRP levels with radiologic findings of perienteric inflammation[12]. Whether involvement of mesenteric adipocytes in the immune response results in an increased CRP level and, in the long run, the course of disease, is a matter of speculation. We could not confirm the data from Floren et al, who reported an exclusive ileal disease distribution in a group of CD patients with a CRP level below the level of 10 mg/L. In this study the LCRP group had a significant lower body mass index as well, while no differences were found in the frequency and distribution of CARD15 variants[23]. The association of colonic disease phenotype, cigarette smoking or the presence of granulomas with relapses as reported in other studies was not reproduced in the current study either[24–30].

Our study has its limitations. The severity of index relapses was scored retrospectively and the presence of relapses during the follow-up period was assumed if certain criteria were met in the charts. We tried to overcome these limitations by using blinded assessment of the index colonoscopies by two gastroenterologists and by defining strict criteria for relapse in the follow-up phase. The number of courses of prednisone had to be scored retrospectively as well, which only gives a global impression. In addition, we had to choose a cut-off level of CRP to create two groups. In literature, there is only one comparable study[23] in which 10 mg/L was used as the cut-off level. We found that a CRP level of 15 mg/L discriminated the two groups optimally.

In conclusion, this study showed that the level of CRP during a relapse of CD can serve as a prognostic factor for the number and severity of relapses. Patients with a CRP level > 15 mg/L experienced more and more severe relapses, were treated more extensively with prednisone and responded better to infliximab therapy. However, we consider these differences too small to be of use in clinical decision making.

Crohn’s disease (CD) may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract and is characterized by a broad spectrum of clinical presentations and a variable disease course. Disease flares occur randomly and cannot be predicted reliably. The aim of the present study was to explore the value of C-reactive protein (CRP) as a prognostic factor with respect to the clinical course of CD.

Early identification of CD patients with a propensity to an aggressive or more benign disease course could be of major clinical importance; this might guide the clinician in deciding what maintenance therapy should be prescribed and could even result in early initiation of aggressive induction therapy to avoid flares or complications. To date, a simple parameter, reliably predicting disease activity and flares is not available. From all laboratory markers, CRP seems to be the most promising candidate in this respect. Not all patients with confirmed disease activity, however, display raised CRP levels. We hypothesized that this group constitutes a distinct, benign phenotype, possibly requiring less intensive treatment.

A high CRP level during relapse is positively correlated with the severity and frequency of relapses. Furthermore, this was found to be associated with longer courses of steroids and a better response following infliximab administration.

These findings suggest that phenotypes can be identified using a biochemical parameter such as CRP, which predicts to a certain extent the course of disease and response to drugs. The differences found in this study, however, are too small to guide clinical decision making and the use of CRP in this setting should be seen as an additive tool.

High CRP and low CRP responders are patients that respectively react with a high CRP level and a low CRP level during a relapse of Crohn’s Disease.

This is an important contribution to the literature of inflammatory bowel disease. The study is well conceived and the report is well written.

| 1. | Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:417-429. |

| 2. | Ahmad T, Tamboli CP, Jewell D, Colombel JF. Clinical relevance of advances in genetics and pharmacogenetics of IBD. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1533-1549. |

| 3. | Farmer RG, Hawk WA, Turnbull RB Jr. Clinical patterns in Crohn's disease: a statistical study of 615 cases. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:627-635. |

| 4. | Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, D'Haens G, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Jewell DP, Rachmilewitz D, Sachar DB, Sandborn WJ. A simple classification of Crohn's disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:8-15. |

| 5. | Louis E, Collard A, Oger AF, Degroote E, Aboul Nasr El Yafi FA, Belaiche J. Behaviour of Crohn's disease according to the Vienna classification: changing pattern over the course of the disease. Gut. 2001;49:777-782. |

| 6. | Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, Parc R, Gendre JP. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:244-250. |

| 7. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5-36. |

| 8. | Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749-753. |

| 9. | Emery P, Gabay C, Kraan M, Gomez-Reino J. Evidence-based review of biologic markers as indicators of disease progression and remission in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2007;27:793-806. |

| 10. | Johnson HL, Chiou CC, Cho CT. Applications of acute phase reactants in infectious diseases. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 1999;32:73-82. |

| 11. | Yeh ET. CRP as a mediator of disease. Circulation. 2004;109:II11-II14. |

| 12. | Colombel JF, Solem CA, Sandborn WJ, Booya F, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Bodily KD, Fletcher JG. Quantitative measurement and visual assessment of ileal Crohn's disease activity by computed tomography enterography: correlation with endoscopic severity and C reactive protein. Gut. 2006;55:1561-1567. |

| 13. | Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Laboratory markers in IBD: useful, magic, or unnecessary toys? Gut. 2006;55:426-431. |

| 14. | Fagan EA, Dyck RF, Maton PN, Hodgson HJ, Chadwick VS, Petrie A, Pepys MB. Serum levels of C-reactive protein in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Eur J Clin Invest. 1982;12:351-359. |

| 15. | Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. C-reactive protein as a marker for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:661-665. |

| 16. | Boirivant M, Leoni M, Tariciotti D, Fais S, Squarcia O, Pallone F. The clinical significance of serum C reactive protein levels in Crohn's disease. Results of a prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;10:401-405. |

| 17. | Shine B, Berghouse L, Jones JE, Landon J. C-reactive protein as an aid in the differentiation of functional and inflammatory bowel disorders. Clin Chim Acta. 1985;148:105-109. |

| 18. | Filik L, Dagli U, Ulker A. C-reactive protein and monitoring the activity of Crohn's disease. Adv Ther. 2006;23:655-662. |

| 19. | Chamouard P, Richert Z, Meyer N, Rahmi G, Baumann R. Diagnostic value of C-reactive protein for predicting activity level of Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:882-887. |

| 20. | Cellier C, Sahmoud T, Froguel E, Adenis A, Belaiche J, Bretagne JF, Florent C, Bouvry M, Mary JY, Modigliani R. Correlations between clinical activity, endoscopic severity, and biological parameters in colonic or ileocolonic Crohn's disease. A prospective multicentre study of 121 cases. The Groupe d'Etudes Therapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives. Gut. 1994;35:231-235. |

| 21. | Solem CA, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. Correlation of C-reactive protein with clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and radiographic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:707-712. |

| 22. | Gonzalez S, Rodrigo L, Martinez-Borra J, Lopez-Vazquez A, Fuentes D, Nino P, Cadahia V, Saro C, Dieguez MA, Lopez-Larrea C. TNF-alpha -308A promoter polymorphism is associated with enhanced TNF-alpha production and inflammatory activity in Crohn's patients with fistulizing disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1101-1106. |

| 23. | Florin TH, Paterson EW, Fowler EV, Radford-Smith GL. Clinically active Crohn's disease in the presence of a low C-reactive protein. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:306-311. |

| 24. | Cosnes J, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, Gendre JP. Smoking cessation and the course of Crohn's disease: an intervention study. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1093-1099. |

| 25. | Lindberg E, Tysk C, Andersson K, Jarnerot G. Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease. A case control study. Gut. 1988;29:352-357. |

| 26. | Silverstein MD, Lashner BA, Hanauer SB, Evans AA, Kirsner JB. Cigarette smoking in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:31-33. |

| 27. | Tobin MV, Logan RF, Langman MJ, McConnell RB, Gilmore IT. Cigarette smoking and inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:316-321. |

| 28. | Heresbach D, Alexandre JL, Branger B, Bretagne JF, Cruchant E, Dabadie A, Dartois-Hoguin M, Girardot PM, Jouanolle H, Kerneis J. Frequency and significance of granulomas in a cohort of incident cases of Crohn's disease. Gut. 2005;54:215-222. |

| 29. | Sahmoud T, Hoctin-Boes G, Modigliani R, Bitoun A, Colombel JF, Soule JC, Florent C, Gendre JP, Lerebours E, Sylvester R. Identifying patients with a high risk of relapse in quiescent Crohn's disease. The GETAID Group. The Groupe d'Etudes Therapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives. Gut. 1995;37:811-818. |