INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic or percutaneous biliary stenting is the preferred method of palliative treatment for malignant biliary strictures[1–4]. As the stents are used frequently and for long periods of time, biliary stent-related duodenal perforation is not an uncommon complication, which is potentially life threatening[5–9]. Biliary metallic stent-induced retroperitoneal perforation resulting in aortoduodenal fistula has not been reported as yet. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing the lethal complication of a bleeding aortoduodenal fistula following biliary metallic stent-related duodenal perforation.

CASE REPORT

A 69-year-old woman presented herself with symptoms of abdominal pain and melena that started to worsen 2 d or 3 d before. An uncovered biliary wall stent (Boston Scientific, Marlboro, MA), 5 cm in length, was inserted two years before when the patient was diagnosed with a locally advanced pancreatic cancer. One year later, endoscopic removal of the uncovered wall stent was attempted because of stent clogging and tumor ingrowth. However, the attempt was unsuccessful, and resulted in a partial deformity of the distal end of the stent. A covered biliary wall stent, 6 cm in length, was reinserted into the stent. The patient received gemcitabine chemotherapy for 2 mo and recently took analgesics. She also frequently received folk remedies, such as massage of the epigastrium with downward palm-pressure.

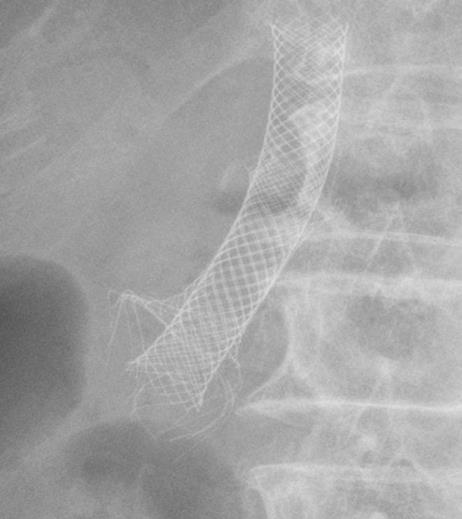

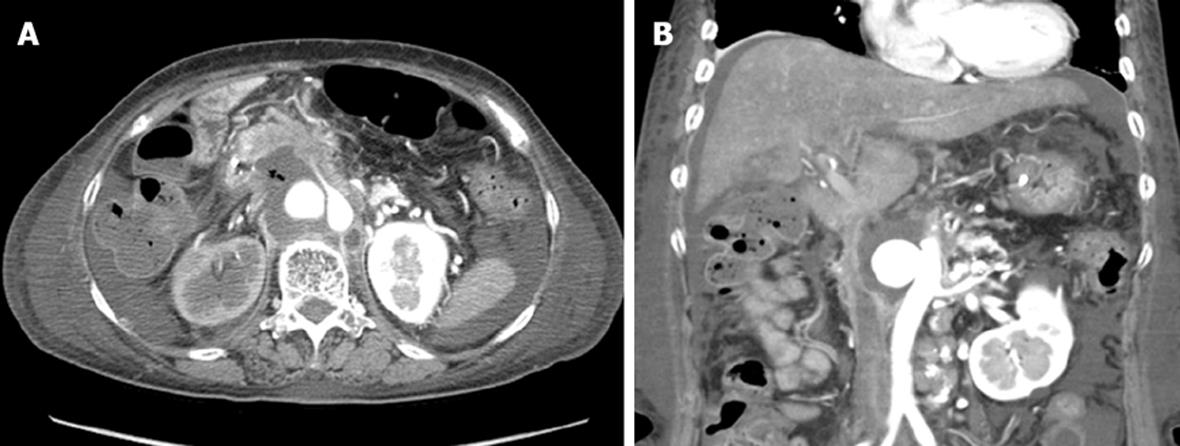

Upon presentation, clinical examination revealed mild epigastric tenderness and abdominal distension without rebound tenderness. Laboratory tests showed 21.88 × 109/L (4.0-10.8 × 109/L) white blood cells, 8.5 g/dL (13-18 g/dL) hemoglobin, 36 IU/L (60-160 IU/L) amylase, 10 IU/L (0-60 IU/L) lipase, and 152 IU/L (39-117 IU/L) alkaline phosphatase. Comparisons of two simple abdominal X-rays, one taken recently and the other 2 mo before, found that the stents were slightly migrated distally and the outer stent’s distal tip was compressed, shooting out radially in all directions (Figure 1). Abdominal computer tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a biliary stent with lesions arising from the head of the pancreas, compressing the second part of the duodenum. Air bubble densities were traced from the pancreatic head to the lower para-aortic lesions (Figure 2).

Figure 1 Simple abdomen examination demonstrating compression of deformed distal tip of the outer biliary metallic stent shooting out radially in all directions.

Figure 2 Abdominal CT scan showing biliary metallic stents with a lesion arising from the pancreatic head and the trajectory of air bubble densities traced from the pancreatic head to the lower paraaortic lesions.

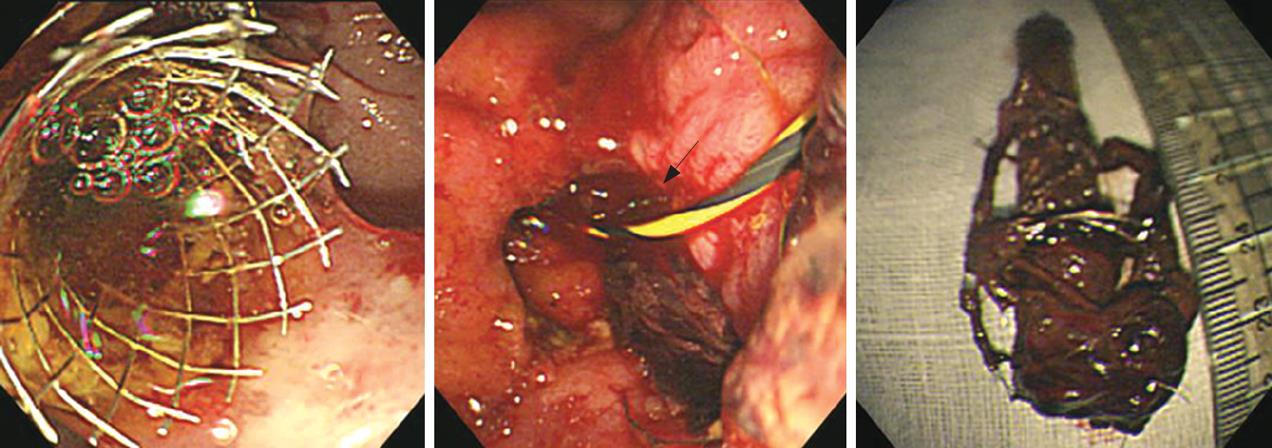

An endoscopy demonstrated that the bare metal barbs deformed in the stent were seen to have impacted and penetrated the neighboring wall of the duodenum. Following removal of the stents with a rat-tooth forceps without any additional injury, a circular hole with bleeding corresponding to the perforation was evident (Figure 3). We then planned to place a covered self-expandable metal stent into the duodenum, instead of placing a nasobiliary drainage for a short time due to desaturation and instability of the patient. After removal of the stent and treatment with parenteral nutrition and intravenous antibiotics, the patient felt well with no abdominal pain. However, 3 d later, she complained again of abdominal pain and melena. So a follow-up abdominal CT was performed, which showed decreased air densities in the same area. However, a newly developed circular contrast collecting aortic aneurysm was found in the adjacent para-aortic lesion (Figure 4). On the following day, unexpected and massive hematemesis and hematochezia occurred, and the patient died due to bleeding.

Figure 3 EGD.

A: On previous admission (one year ago), placement of a stent into a stent due to clogging; B: On the present admission, a circular hole with bleeding (arrow) caused by stent-induced perforation following removal of stents; C: Retrieved biliary metallic stents showing deformed barbs of the uncovered wall stent tip on the distal portion of the covered wall stent.

Figure 4 Abdominal CT scan showing decreased air densities in the pancreatic head to the paraaortic area (A) and a circular contrast collecting aneurysm of aorta (B).

DISCUSSION

Early occurrence of iatrogenic duodenal perforations is generally apparent during papillotomy and stent placement. Late presentations of duodenal perforations caused by biliary prosthesis are much rarer, but they are potentially life threatening and require immediate management[10–12].

Although the uncovered wall stent is easily embedded in the bile duct epithelium[1314], the prolonged in situ uncovered wall stent may lose its framework, causing the stent to become weak because of its woven structures. In the present case, the stent’s distal end was partially destroyed by repeated tries to remove it and it might have migrated distally during the follow-up. Under these circumstances, with repeated external abdominal pressure, the inner covered stent might have acted on the distal tip of the outer uncovered wall stent as a vehicle with a straining and compressing force. These factors are believed to have increased the intensity of trauma to the adjacent duodenal wall. Consequently, the deformed wire barbs of the outer wall stent’s distal tip caused stent-induced retroperitoneal perforation and fistula.

The mainstays of treatment for early perforations without systemic upset are nasogastric suction, antibiotics, bowel rest and parenteral nutrition[15]. Our patient received conservative treatment and improved after stent removal. However, the patient suddenly bled to death due to the onset of an aortic aneurysm, the aortic wall might have been eroded as a result of retroperitoneal para-aortic irritation or inflammation through the fistula.

In summary, we can learn some lessons from this case. One is that stent-induced late perforation and related lethal complications may develop as a result of a distally migrated uncovered stent with sharp distal barbs and deformity caused by repeated stent removal trials and external abdominal pressure. The other is that early diagnosis and management are essential to prevent significant complications.