INTRODUCTION

Cholangiocytes are simple epithelial cells that line the intrahepatic biliary tract, which is a three-dimensional network of interconnecting ducts. The primary physiological function of cholangiocytes is the modification bile of canalicular origin and drainage of bile from the liver[1]. In addition to their role in the modification of ductal bile, cholangiocytes also participate in the detoxification of xenobiotics[1]. In recent years, interest in the study of cholangiocytes has increased dramatically due to a rise in the incidence of cholestatic liver diseases and biliary tract cancers (i.e. cholangiocarcinoma) in patients worldwide[2–5].

In diseases of the biliary tree (e.g. primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), liver allograft rejection and graft-versus-host disease), cholangiocytes are the primary target cells[1]. These cholangiopathies cause morbidity and mortality and are a major indication for liver transplantation[1]. In fact, these diseases contribute to 20% of the liver transplants in adults and 50% of those in pediatric patients[6]. Proliferation of cholangiocytes is critical for the maintenance of biliary mass and secretory function during the pathogenesis of chronic cholestatic liver diseases, such as primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Previous studies have demonstrated that proliferating cholangiocytes serve as a neuroendocrine compartment during liver disease pathogenesis and as such secrete and respond to a number of hormones and neuropeptides contributing to the autocrine and paracrine pathways that modulate liver inflammation and fibrosis, which are predicted to play key roles in cholangiocarcinogenesis[7].

Cholangiocarcinomas are adenocarcinomas that arise from the neoplastic transformation of cholangiocytes. Cholangiocarcinoma occurs in approximately 2 per 100 000 people and account for approximately 13% of primary liver cancers[4]. Cholangiocarcinomas can be divided into three categories based upon anatomic location: (1) intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, occurring in the bile ducts residing within the liver; (2) hilar cholangiocarcinoma, occurring at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts; and (3) distal extrahepatic bile duct cancers[8]. The prognosis for cholangiocarcinoma is grim due to lack of early diagnostic modalities and effective treatment paradigms. Cholangiocarcinomas are slow growing, metastasize late during the cancer’s progression, and present with symptoms of cholestasis due to the blockage of the bile duct by tumor growth[8]. In most cases, the tumors are well advanced at the time of diagnosis, which results in limited treatment options[9]. Many of these tumors are too advanced to be removed surgically and chemotherapy and radiation therapy usually are not effective, which indicates the dire need to understand the mechanisms that activate the neoplastic transformation of cholangiocytes and control the growth of cholangiocarcinomas.

RISK FACTORS FOR CHOLANGIOCARCINOMA

Several recent studies have shown that there is an increasing incidence of cholangiocarcinoma world-wide and in particular in Western countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia[410–12]. Although most patients do not have identifiable risk factors for the disease, several risk factor have been established for cholangiocarcinoma[13]. The list of risk factors includes: gallstones or gallbladder inflammation, chronic ulcerative colitis, chronic infection of liver flukes, Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini, and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)[14]. In addition, a recent study revealed several novel risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma[15]. Hepatitis C virus infection, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, obesity and smoking are all associated with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma[15]. The majority of these risk factors have the common features of chronic liver inflammation, cholestasis, and increased cholangiocyte turnover[1617].

MOLECULAR MECHANISMS CONTRIBUTING TO CHOLANGIOCARCINOGENESIS

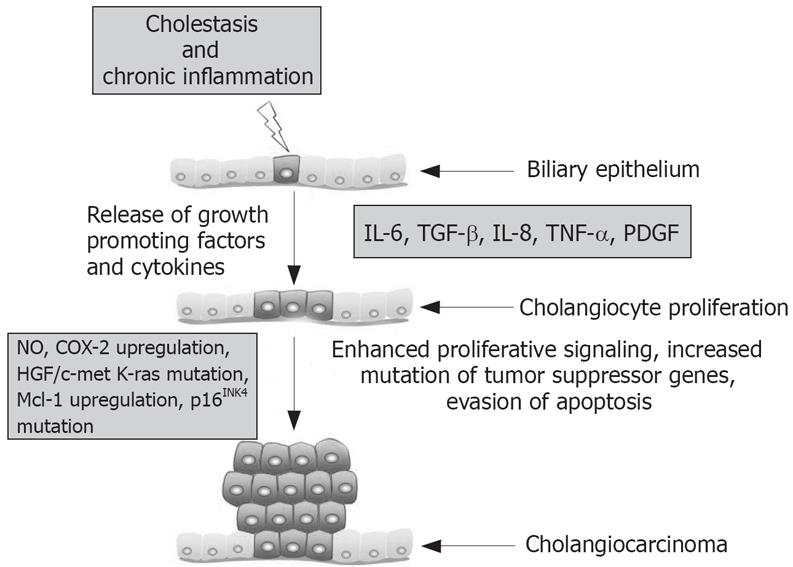

A common and important contributor to the malignant transformation of cholangiocytes is chronic inflammation of the liver. This inflammation is often coupled with the injury of bile duct epithelium and obstruction of bile flow, which increases cholangiocyte turnover (i.e. dysregulation in the balance of cholangiocyte proliferation and apoptosis)[918]. Persistent inflammation is thought to promote carcinogenesis by causing DNA damage, activating tissue reparative proliferation, and by creating a local environment that is enriched with cytokines and other growth factors[19]. Thereby, chronic inflammation creates local environmental conditions that are primed for cells to develop autonomous proliferative signaling by constitutive activation of pro-proliferative intracellular signaling pathways and enhanced production of mitogenic factors. Indeed recent studies have demonstrated that cholangiocytes release cytokines, such as interleukin 6 (IL-6), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), IL-8, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and platelet–derived growth factor (PDGF). These factors can interact with cholangiocytes in an autocrine/paracrine fashion to regulate cholangiocyte intracellular signaling responses, which are thought to be altered during cholangiocarcinogenesis[20].

Cytokines activate inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in cholangiocytes. This results in the generation of nitric oxide, which along with other reactive oxygen species, may alter DNA bases, result in direct DNA damage and trigger the downregulation of DNA repair mechanisms[18]. Nitric oxide can directly or through the formation of peroxynitrite species can lead to the deamination of guanine and DNA adduct formation thereby promoting DNA mutations[1821]. The resultant DNA damage leads to an increased mutation rate and alteration of genes critical to cell proliferation control. Consistent with this line of thought, activating mutations and the overexpression of EGFR, erb-2, K-ras, BRAF and hepatocyte growth factor/c-met (HGF) have been reported for cholangiocarcinoma. In addition, the proto-oncogene c-erbB-2 is activated in patients with cholangiocarcinoma[2223]. Mutations affecting the promoter of the tumor suppressor p16INK4a that result in loss of transcription occur in both PSC and PSC-associated cholangiocarcinoma[24]. Alterations of p53, APC, and DPC4 tumor suppressor genes by a combination of chromosomal deletion, mutation, or methylation; and infrequently microsatellite instability have also been linked to cholangiocarcinoma[25]. In addition to increased ability of cholangiocytes to escape from senescence, activation of iNOS promotes the upregulation of COX-2 in immortalized mouse cholangiocytes suggesting that COX-2 and COX-2 derived prostanoids might play a key role in cholangiocarcinogenesis[2627]. COX-2 also upregulated the expression of Notch, which has been implicated in other cancer types[27].

Cytokines, such as IL-6, appear to play an important role in cholangiocyte evasion of apoptosis. During the pathogenesis of cancer, the activation of evasion of apoptosis pathways helps to prevent cells with accumulating DNA damage from undergoing cell death pathways that normally eliminate such dysfunctional cells. Cholangiocarcinoma cells have been shown to secrete IL-6 and in an autocrine fashion IL-6 activates the pro-survival p38 mitogen activated protein kinase[28]. In fact, IL-6 upregulated the expression of myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1) expression through STAT3 and AKT signaling pathways[2930]. Mcl-1 is an anti-apoptotic protein in the Bcl-2 family of apoptotic proteins. Recently, the cellular expression of Mcl-1 has been shown to be controlled by the small endogenous RNA molecule, mir-29, which is down regulated in malignant cells consistent with Mcl-1 overexpression[31]. Enforced expression of mir-29 reduced Mcl-1 expression the malignant human cholangiocytes, KMCH[31]. Modulation of expression small endogenous RNAs such as mir-29 might represent a therapeutic paradigm for cholangiocarcinomas.

FACTORS REGULATING CHOLANGIOCARCINOMA GROWTH

A number of recent studies have shown that the nervous system, neuropeptides and neuroendocrine hormones play a key role in the modulation of cholangiocarcinoma growth[32]. We have demonstrated that proliferating cholangiocytes serve as a neuroendocrine compartment during liver disease pathogenesis and as such secrete and respond to a number of hormones and neuropeptides contributing to the autocrine and paracrine pathways that modulate liver inflammation and fibrosis[7]. The sympathetic nervous system has been shown to have a role in the negative regulation of cholangiocarcinoma growth[33]. The cholangiocarcinoma cell lines, Mz-ChA-1 and TFK-1, express the α2A-, α2B-, and α2C-adrenergic receptor subtypes[33]. Stimulation of the α2 receptors induced an upregulation of intracellular cAMP, which inhibited EGF-induced MAPK activity through an increase in Raf-1 and the sustained activation of B-raf, which resulted in the subsequent reduction of cholangiocarcinoma proliferation[33]. Although muscarinic acetylcholine receptor are expressed by cholangiocytes and play a role in regulating secretin-induced bile flow in rodents, the role of the parasympathetic nervous system has not been evaluated in cholangiocarcinoma and warrants consideration as a factor regulating cholangiocarcinoma growth[3435].

Other neuroendocrine hormones and neurotransmitters have also been shown to play a role in the regulation of cholangiocarcinoma growth. The cholangiocarcinoma cell lines, Mz-ChA-1, HuH-28 and TFK-1, express the gastrin/CCK-B receptor and gastrin inhibits the proliferation and induces the activation of apoptosis in these cholangiocarcinomas through the activation of Ca2+-dependent PKC-α signaling. Most recently, Fava et al have shown that γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) inhibits cholangiocarcinoma cell proliferation and migration[36]. This effect was also evident in vivo with GABA significantly decreasing the growth of cholangiocarcinoma tumor xenografts in nude mice[36].

Female steroid hormones, such as estrogens, have also been shown to play a role in the promoting of cholangiocarcinoma cell growth. 17-β estradiol stimulated the proliferation of human cholangiocarcinoma cells in vitro, which was blocked by tamoxifen[37]. Alvaro et al have demonstrated that human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas express the receptors for both estrogens and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1)[38]. Their study indicates that estrogens and IGF-1 coordinately regulate cholangiocarcinoma growth and apoptosis[38].

Modulation of the endocannabinoid system is currently being targeted to develop possible therapeutic strategies for other cancer types. We recently demonstrated the novel finding that the two major endocannabinoids, anandamide and 2-arachidonylglycerol, have opposing actions on cholangiocarcinoma growth[39]. Interestingly, anandamide was found to be antiproliferative and to promote apoptosis, while, in contrast, 2-arachidonylglycerol stimulated cholangiocarcinoma cell growth[39]. Anandamide was shown to recruited Fas and Fas ligand into lipid rafts resulting in the activation of death receptor pathways and apoptosis in the cholangiocarcinoma cells[39].

CONCLUSION

Cholangiocarcinoma is a devastating neoplasm of the biliary tract that is increasing in incidence. While treatment options are limited, our knowledge base of the factors controlling cholangiocarcinogenesis and cholangiocarcinoma growth has greatly expanded in the past decade. These studies have clearly demonstrated that, during the course of chronic cholestasis and associated liver inflammation, a number of factors are released into the local environment that set into motion a series of events compound genomic damage leading to autonomous proliferation and escape from apoptosis (Figure 1). Several potential areas seem promising for the development of prevention and treatment strategies for cholangiocarcinoma. In particular, inhibition of the COX-2 pathway during PSC warrants further investigation. Also, modulation of cholangiocarcinoma growth by the regulating neural imput or the endocannabinoid system might prove fruitful. Understanding the molecular mechanisms triggering biliary tract cancers will be key for the development of new treatments and diagnostic tools for cholangiocarcinoma.

Figure 1 Summary of key mechanisms regulating cholangiocarcinogenesis.

Supported by a grant award (#060483) to Dr. Glaser from Scott and White Hospital