INTRODUCTION

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) produced in some cancers is thought to be an autocrine growth factor[12]. Therefore, patients with G-CSF-producing cancer generally have a poor prognosis, and early diagnosis and treatment are required. Biliary cancer, such as cholangiocellular and gallbladder carcinoma are reported to produce G-CSF in some cases[3–10], however, extrahepatic bile duct cancer that produces G-CSF has not yet been reported.

This report describes a case of extrahepatic bile duct cancer that produced G-CSF, in which neither regional lymph node metastasis nor massive progression was observed by radiological examination, but autopsy showed multiple organ metastasis.

CASE REPORT

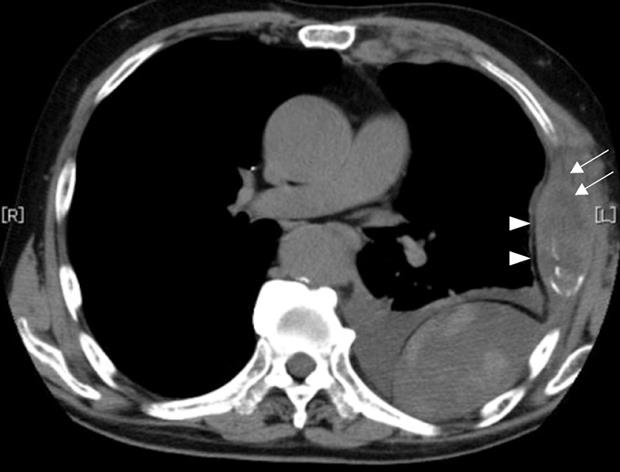

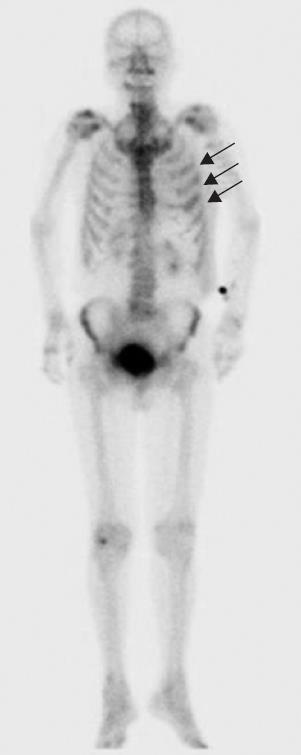

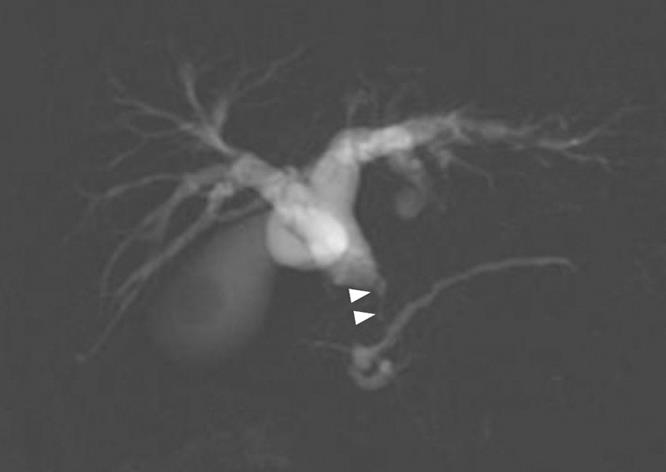

A 79-year-old man who suffered from left lateral chest pain for one month was referred to our department for treatment of a tumor on the left chest wall and extrahepatic bile duct cancer found during an annual medical examination. His body temperature was 36.9°C. From the left axillar to anterior axillary line of the left chest wall, many nodules, 5-10 mm in diameter, were palpated, without tenderness. He had no history of chest trauma. Chest radiography showed massive pleural effusion and a tumor that elevated smoothly from the left chest wall, near which the fifth rib could not be traced (Figure 1). Enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) depicted a mass with necrosis inside the tumor and enhancement on its border, as well as two osteolytic lesions on the seventh thoracic vertebra, swelling of many anterior mediastinal and left axillary lymph nodes, and pleural effusion around extrapleural fluid collection (Figure 2). Enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest showed extensive enhancement of the muscle and connective tissue around the ribs, as well as a cavity within the muscle. Bone scintigraphy showed an abnormal opaque uptake in the left third to fifth ribs and vertebrae (Figure 3). Cytodiagnosis of the pleural and extrapleural effusion showed solitary atypical cells, regarded as histiocytes, scattered in numerous inflammatory cells. Those atypical cells had swelling nuclei and a distinct eosinophilic nucleolus; however, it was difficult to diagnose the lesion as an adenocarcinoma from the chromatin pattern. Abdominal CT demonstrated a gradually enhanced tumor in the distal bile duct, without any regional lymph node and liver metastasis (Figure 4), and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed stenosis of the distal common bile duct (Figure 5). Laboratory data showed an increase in the following: white blood cell count (WBC) 21 460 cells/&mgr;L (neutrophils, 18 240 cells/&mgr;L), ALP 536 IU/L, γ-GTP 300 IU/L, LDH 251 IU/L, CRP 4.33 mg/dL, but carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and DU-PAN-2, a tumor marker which is especially elevated in pancreato-biliary cancer patients, were within the normal limit. The neutrophil alkaline phosphatase (NAP) score was elevated to 381 to exclude chronic myeloblastoid leukemia.

Figure 1 Chest radiography revealed massive plural effusion and a tumor elevating smoothly from the left chest wall (arrowheads), near which the fifth rib could not be traced.

Figure 2 Chest CCT depicted a mass with necrosis inside the tumor (arrows) and enhancement of its border (arrowheads), and extrapleural tumor and pleural effusion.

Figure 3 Bone scintigraphy showed an abnormal opaque uptake in the left third to fifth ribs (arrows).

Figure 4 Abdominal CT revealed a gradually enhanced tumor in the distal bile duct (arrows), without any regional lymph node or liver metastasis.

Figure 5 MRCP revealed stenosis (arrow heads) of the distal common bile duct.

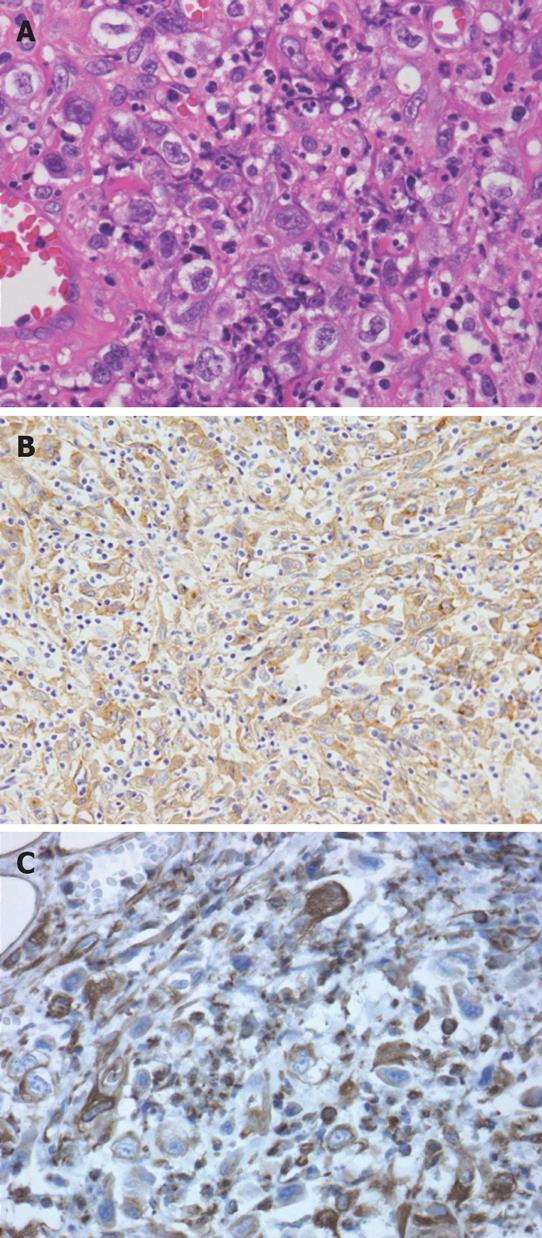

Histological examination of the nodule on the chest wall that was partially resected for diagnosis revealed scattered atypical cells among numerous fibroblasts, macrophages and neutrophils in the skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. These atypical cells showed positive immunohistochemical staining for pan-cytokeratin and vimentin, but not for desmin, which excluded leiomyosarcoma (Figure 6). Since such atypical cells had no epithelial connection or basement membrane, they were thought to be reactive mesothelial and not carcinoma cells. Therefore, the pathological diagnosis was considered to be either proliferative myositis or nodular fasciitis-like granuloma.

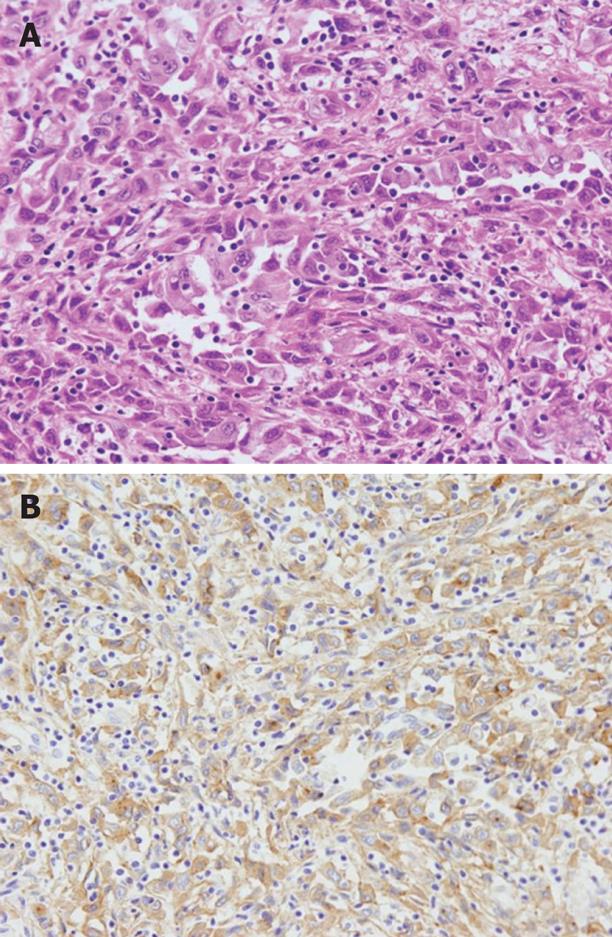

Figure 6 Histological examination of the resected chest wall showed scattered atypical cells among numerous inflammatory cells (A).

Immunohistochemistry for pan-cytokeratin as an epithelial cell marker (B) and vimentin as a mesenchymal cell marker (C) both showed positivity in these atypical cells.

Eighteen days after admission the patient’s appetite, consciousness and daily activity deteriorated, and WBC was elevated to 86 050 cells/&mgr;L (neutrophils, 80 880 cells/&mgr;L) without pyrexia. Until then, no bacterium was seen in the sputum, pleural effusion and fluid in the chest wall cavity. Expecting an improvement of his general condition and inflammation of myositis on the left chest wall, we drained pleural effusion fluid and the patient received an injection of dexamethasone. However, his general condition and laboratory data did not improve. WBC increased to 106 040 cells/&mgr;L (neutrophils, 91 900 cells/&mgr;L) before death. Twenty-seven days after admission, a multiple cerebral infarction was found, which had not been observed 7 d earlier. The patient died the following day and underwent an autopsy.

The autopsy revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with sarcomatous change, which had slightly invaded into the pancreas in the distal bile duct (Figure 7A). In addition, no other primary cancer was observed macroscopically in the chest and abdomen. The cancer cells showed positive immunohistochemical staining for G-CSF (Figure 7B). The G-CSF concentration in serum samples archived by the hospital was 53, 38 and 134 pg/mL on 21, 23 and 26 d after admission, respectively (normal < 18 pg/mL). This result was obtained 9 d after death. In a specimen of the left chest wall, solitary cancer cells, numerous surrounding inflammatory cells such as neutrophils and macrophages, had invaded into the skeletal muscles, similar to the biopsy tissue. Therefore, the pathological diagnosis of the left chest wall was a metastasis of the bile duct carcinoma with sarcomatous change, and the anterior mediastinal lymph nodes showed the same histological findings. Moreover, under the serosa of the mesentery and liver, some white nodules, measuring 5 mm in diameter, were macroscopically discovered and their histology showed them to be metastases. In addition, histological examination of all the organs in the chest and abdomen demonstrated multiple metastases in the lung, kidney, adrenal gland, mesentery, vertebral bone marrow and mediastinal and para-aortic lymph nodes. In contrast, no metastasis was found in the regional lymph nodes. These findings proved the presence of extensive systemic dissemination of cancer cells.

Figure 7 Histological examination revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with sarcomatous change in the distal bile duct, which slightly invaded into the pancreas (A), and cancer cells showed positive immunohistochemical staining for G-CSF (B).

DISCUSSION

This is believed to be the first report of an extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma that produces G-CSF. A search of PubMed by the key words CSF and biliary cancer, revealed three and five reports, respectively, of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma[3–10], but there have so far been no reports of extrahepatic bile duct malignancy. While two of these patients underwent curative surgery and survived without recurrence for 18 mo and 27 mo, respectively[68], three patients died within 6 mo after palliative or exploratory surgery[359]. In one case, the details of the surgery were unknown[4], and the other was a report of archival histological examination[7]. In a case of rapid progression, the patient died 5 d after admission[10]. As with other organs such as the lung, thyroid and kidney, the prognosis of G-CSF-producing carcinoma in the biliary tract is considered to be poor, and early diagnosis and surgical treatment are needed. In the present case, surgery could not have been performed, even if the diagnosis had been done correctly and rapidly. However, an early examination of G-CSF in the serum would have identified the lesions as multiple metastasis of a common bile duct cancer, thereby leading to more appropriate treatment, such as chemotherapy. To avoid wasting time with additional radiological examination and inefficient treatment such as antibiotics for leukocytosis, G-CSF in serum should be examined when bacterial infection is ruled out for leukocytosis by a routine preoperative examination.

In this case, it was not possible to diagnose the correct extent of the carcinoma, in spite of various radiological and pathological data. This was because the accumulation of inflammatory cells induced by G-CSF produced by the cancer cells in the metastatic lesions mimicked inflammation of the chest wall and vertebra in the radiological and pathological examinations. Furthermore, the lack of loco-regional lymph node and liver metastases in the radiological examination led us to consider other lesions in the differential diagnosis, such as mediastinal lymphadenopathy and chest wall nodules, as an inflammatory reaction from the left chest wall lesion. Although endoscopic ultrasonography was not performed in this case, the loco-regional stage of cancer was diagnosed as stage Ia or Ib. This type of dissociation between the loco-regional and whole body extent of carcinoma has occasionally been reported with gastric cancer[11–13], however, no report has been found regarding extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma. Scattered carcinoma cells in many inflammatory cells, thus indicating sarcomatous change, could not be correctly diagnosed due to these changes, such as the loss of basal membrane and intercellular connection between cancer cells. Shimada et al[14] have reported cholangiocarcinomas with two types of sarcomatous change, spindle and pleomorphic type, which have very poor prognosis, especially the latter type. Moreover, Nakajima et al[15] have shown aggressive intrahepatic spreading and widespread metastasis of the sarcomatous cells of an intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. In the present case, dissociation between the findings of the loco-regional and whole body examination might have been due to sarcomatous change and G-CSF, which is thought to be a growth factor. For a case of extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma that produces G-CSF, an examination for distant metastasis, such as bone scintigraphy and chest CT, should be considered.