INTRODUCTION

Lead is a toxic metal that affects many organ systems and functions in humans. In the majority of adults, chronic lead poisoning comes from exposures to work places and can occur in numerous work settings, such as manufacturing, lead smelting and refinement or due to use of batteries, pigments, solder, ammunitions, paint, car radiators, cable and wires, certain cosmetics[1]. In some countries, lead is added to petrol. Inorganic lead is absorbed from the respiratory or gastrointestinal tract. Approximately 30%-40% of inhaled lead is absorbed into the blood stream[2]. Gastrointestinal absorption varies depending on nutritional status and age. Iron is believed to impair lead uptake in the gut, while iron deficiency is associated with increased blood lead concentrations in children. Once absorbed, 99% of circulating lead is bound to erythrocytes for approximately 30-35 d (only 1% of absorbed lead is found in plasma and serum) and is dispersed into the soft tissues of liver, renal cortex, aorta, brain, lungs, spleen, teeth, and bones in the following 4-6 wk. The clinical manifestations can vary from individual to individual. Diagnosis of lead toxicity is mainly based on the elevated blood lead levels (BLL). There is a general correlation between toxic effects of lead and BLL. New data implicate that lower blood lead levels, previously considered normal, can cause cognitive dysfunction, neurobehavioral disorders, different neurological damages, hypertension and renal impairment[3–6].

Toxicity of petrol is usually associated with inhalation of vapor leading to dysfunction of the central nervous system. Ingestion of petrol by adults is rare and happens accidentally during siphoning of petrol tanks. The incidence of petrol ingestion in children is relatively low. An accidental ingestion of petrol causes acute symptoms of gastrointestinal tract including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. We report a rare case of extreme gastric dilation caused by long-term petrol ingestion.

CASE REPORT

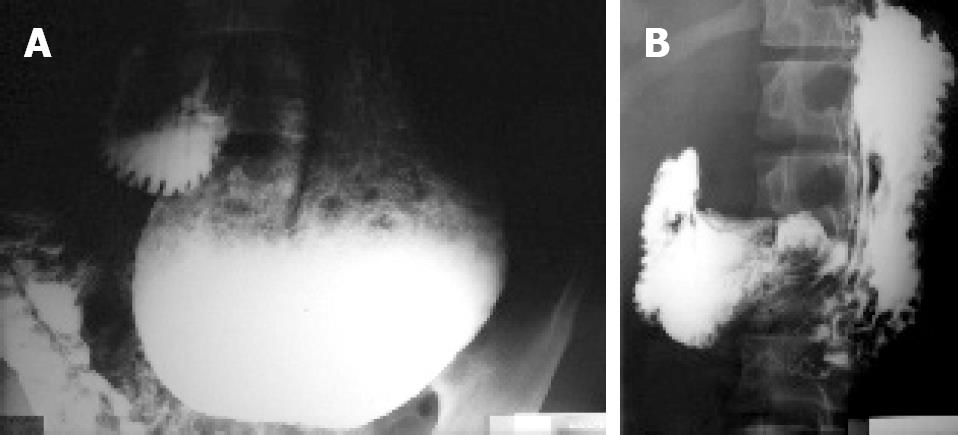

A previously healthy 16-year-old young man was admitted to our hospital due to a 6-mo history of exhaustion, dizziness, nausea, abdominal cramps and constipation. He was not drug addictive. At admission to our hospital, he was pale, with slightly icteric eyes, normal heart and lungs, generalized abdomen tenderness, but no hepatosplenomegaly. Neurological examination was normal. Laboratory investigation revealed normocytic anemia, 117 g/L hemoglobin, 7 &mgr;mol/L iron (normal 11-30 &mgr;mol/L), 26 &mgr;mol/L bilirubin (normal 0-20 &mgr;mol/L), 21 &mgr;mol/L unconjugated bilirubin, 41 IU/L AST (normal 0-30 IU/L), 56 IU/L ALT (normal 0-41 IU/L). Blood tests showed that white blood cells, platelets, urea, creatinine, acid uric, albumin, HBsAg, anti-HCV, anti-HIV, and urine were normal or negative. Chest radiography and abdominal ultrasound were normal. X-ray examination of the stomach revealed extreme gastric dilation (Figure 1A). The stomach descended into the pelvis. Gastroscopy showed chronic erosive gastritis. Colonoscopy was normal. After supportive therapy, the patient was discharged without explanation for gastric dilation. Control hospitalization in our hospital was four months later. During that time, he was feeling well and had no abdominal pains. Physical examination at admission was normal. Laboratory investigations displayed that hemoglobin was decreased to 111 g/L and iron to 8 &mgr;mol/L while bilirubin was increased to 32 &mgr;mol/L (unconjugated 30 &mgr;mol/L). Red blood cells, white blood cells, aminotransferases, urea, creatinine, acid uric and urine returned to normal. Coombs test was negative. Stool examination was negative for parasites. X-ray examination of stomach was the same as in previous hospitalization. Then we intended to do more aggressive medical examinations but the patient told that he was selling petrol on the street before he had symptoms three years ago. It was an illegal work and the patient was afraid to admit it before. During the siphoning, he often swallowed a small amount of petrol. We, therefore, determined his lead blood level (BLL) which was 30 mcg/dL (normal < 10.0 mcg/dL). Urinary excretion of aminolevulinic acid was normal. It was obvious that the patient had chronic lead poisoning but we did not treat him because his condition was good due to no longer lead exposure. We saw the patient four years later during his military service. In that period, he sometimes felt nausea and paresthtesia in fingers and toys. Physical examination was normal. Laboratory analyses were normal except for an increased bilirubin value of 43 &mgr;mol/L (unconjugated 37 &mgr;mol/L). Serum lead concentration was normal (2.66 mcg/dL). X-ray examination revealed that his stomach retuned to its normal size and position (Figure 1B). Nerve conduction studies showed mixed sensory-motor polyneuropathy.

Figure 1 X-ray examination showing dilated stomach descending into the pelvis (A) and the stomach having returned to its normal size and position (B).

DISCUSSION

Lead is widely dispersed in the environment. In the world, the main sources of lead exposure are gasoline additives, food-can soldering, lead-based paints, ceramic glaze and drinking water systems, cosmetic and folk remedies. In literature, there are single reports on long-term lead exposure and few reports on lead poisoning from retained bullets[78]. Two-year consumption of homemade wine can cause lead poisoning[9]. Chronic lead poisoning has many symptoms and signs, including pains, numbness or tingling of the extremities, muscular weakness, headache, loss mood disorders, reduced sperm count, and abnormal sperm. Our patient had mixed sensory-motor polyneuropathy and anemia. Lead has effects on cell membrane, interfering with various energy and transport systems, which may explain why it can shorten erythrocyte survival time and cause anemia. Peripheral blood smear could show basophilic stippling in several red cells from a patient with lead poisoning. Lead can interfere with the heme synthetic pathway especially enzyme delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase causing accumulation of aminolevulinic acid and increasing urinary excretion. Since aminolevulinic acid could be detected in urine only when BLL exceeds 35 mcg/dL, it is not a marker of low lead toxicity[10]. Our patient had a lower BLL and normal urinary aminolevulinic acid excretion. Gastrointestinal manifestations of lead poisoning include chronic or recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation, bloating, anorexia and weight loss[11–13]. These symptoms associated with anemia could lead to toxic etiology especially in the absence of other causes. Our patient had a 6-mo history of unexplained abdominal cramps after stopping petrol ingestion. Generally, all toxic effects of petrol are associated with vapor inhalation. A few minutes after vapor inhalation, symptoms resembling alcohol intoxication (dizziness, excitement, incoordination, etc) occur[14]. Accidental ingestion of petrol is very rare and may cause symptoms of acute gastrointestinal irritation. The main health effect associated with petrol exposure is pneumonitis, resulting from pulmonary aspiration of vomitus following ingestion[1516]. No report on long-term petrol ingestion is available. In addition to a number of potentially neurotoxic chemicals (benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene, n-hexane, etc), lead in petrol is a main additive. Since 2000 in most countries, petrol has only been commercially available in unleaded form, but our patient in Serbia, was selling petrol with lead. When lead is inhaled or absorbed through skin, it is toxic to humans. We could not find any other similar case of extreme gastric dilation caused by lead. Srebocan et al[17] have described gastric dilation in a dog with lead poisoning. The pathogenesis of such dilation remains uncertain, but it seems that lead has a paralytic action on gastrointestinal system. Normal gastrointestinal motor function is a complex series of events that require coordination of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, neurons within the stomach and intestine, and the smooth muscle cells of the gut. Abnormalities of this process can delay gastric emptying (gastric stasis) and gastric tonus (gastric ptosis). It seems that reduction of heme body pool caused by lead impairs cyto-dynamics impairing nerve conduction and paralysis of stomach. Diagnostic evaluation of adults with potential lead toxicity includes medical and environmental history, searching for potential sources of exposure, signs and symptoms of lead poisoning, and laboratory examination. BLL is essential for the diagnosis of lead poisoning. However, BLL measures current exposure to lead, but lead may also be incorporated into bone due to prior exposures not shown in BLL until this bone-lead becomes "mobilized" through pregnancy or fracture healing. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) equipment can be used to measure lead concentrations in bones[18]. The standard elevated BLL is above 25 mcg/dL in adults and above 10 mcg/dL in children. BLL was 30 mcg/dL in our patient ten months after stopping petrol ingestion. The decision to treat it with chelating agents depends on a number of factors, including presence of lead-related symptoms, current BLL, duration of excessive lead exposure and symptoms. Patients with BLL over 80 mcg/dL should be treated[19]. Chelation therapy is recommended for individuals with blood lead levels between 40 mcg/dL and 80 mcg/dL if they have lead-related symptoms. The main chemicals used in chelation therapy are ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) administered through injection and oral drug dimercaprol (BAL). Since our patient had a lower BLL, he could recover by avoiding exposure to lead.

In conclusion, this case illustrates that lead poisoning should be taken into consideration in all unexplained cases of gastric dilation.

Peer reviewer: Hitoshi Asakura, Director, Emeritus Professor,

International Medical Information Center, Shinanomachi Renga

Bldg.35, Shinanomachi, Shinjukuku, Tokyo 160-0016, Japan