Published online Apr 28, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2586

Revised: March 5, 2008

Published online: April 28, 2008

Chordomas are rare tumors which originate from the remnants of the notochord. These tumors are locally aggressive and have a predilection for the ends of the axial skeleton. An important prerequisite for optimal management of these tumors is a correct preoperative diagnosis. The present case is the first report of the use of endoscopic ultrasound to obtain transrectal fine needle aspiration biopsy of a presacral chordoma. A review of the prior computer tomography (CT) scans allowed us to calculate the tumor volume doubling time (18.3 mo). Transrectal biopsy of chordomas is controversial, however we believe that such concerns are not justified.

- Citation: Gottlieb K, Lin PH, Liu DM, Anders K. Transrectal EUS-guided FNA biopsy of a presacral chordoma-report of a case and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(16): 2586-2589

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i16/2586.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.2586

Presacral chordomas are rare tumors that pose radiographic and clinical diagnostic challenges. In most instances, a preoperative pathological diagnosis is important in order to plan the optimal management strategy. Tumors located deep in the pelvis pose technical challenges due to the loco-regional anatomy. Although several methods of obtaining tissue [surgical, computer tomography (CT) guided and percutaneous ultrasound guided sampling] have been described, there is much controversy regarding the appropriateness of transrectal biopsy in patients with a suspected chordoma. Transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy (TRUS) of lesions of the prostate is well established, however, the size and nonflexible nature of the transducers is a limiting factor. A Medline search using search terms chordoma, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) (or endosonography) produced no results. In this article, we describe the first reported use of EUS with fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy for the characterization and diagnosis of a presacral chordoma. We discuss the pathophysiology of chordoma, and the controversies that surround the use of transmural biopsy.

A 60-year-old registered nurse who had undergone a radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer 6 years ago presented with increasing pelvic pain. The PSA was non-detectable. The patient was concerned about recurrence of the prostate cancer. A non-contrast pelvic CT scan demonstrated a presacral tumor measuring 45.9 mm by 35.3 mm (Figure 1). Pelvic CT scans from 6 years ago, that were obtained as part of his prostate cancer work-up, were reviewed. In retrospect, these showed a pubococcygeal tumor measuring 17.6 mm by 14.8 mm. Using an ellipsoid volume formula, the tumor volume doubling time was determined to be 548 d (18.3 mo).

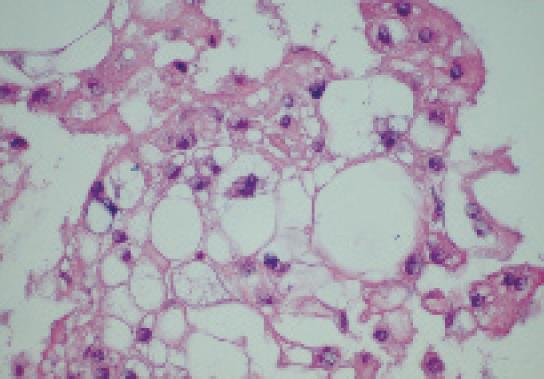

The patient was referred for EUS, which revealed a well circumscribed, echo-rich tumor with a safe window for FNA (Figure 2). FNA biopsies were obtained using the Olympus GF-UC140P curved-linear array echoendoscope (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan). Quick stains suggested mesenchymal origin of the tumor. The final cytology and immunohistochemistry was diagnostic of a chordoma (Figure 3).

Chordomas are rare tumors which are locally aggressive but rarely metastasize. In the United States, the age-adjusted incidence is 0.8 per million[1]. Chordomas are believed to arise from benign notochordal remnants. However, this theory has recently been challenged by Yamaguchi et al who proposed that chordomas instead arise from benign notochordal cell tumors[2]. The microscopic hallmark of these tumors is the presence of characteristic large cells with numerous cytoplasmic vacuoles known as physaliphorous (Greek: droplet bearing) cells. Chordomas constitute only a small percentage of osseous or neurogenic tumors, and are rarely seen in children or adolescents. Men are affected more frequently than women[1]. Although not malignant in the usual sense, chordomas are locally destructive and have a remarkable tendency for local recurrence after cytoreductive surgery. The tumors can also metastasize. Chordomas are rare in humans, but in a series of 533 ferrets with tumors, chordomas constituted 5% of all neoplasms and 86% of bone tumors[3]. About one-half of chordomas are located in the sacro-coccygeal region and approximately 30%-35% are present at the base of the skull. However, chordomas can occur anywhere along the vertebral column[1]. Macroscopically, the tumors are lobulated gelatinous and brownish-grey in color, and occasionally appear translucent. Histologically, these tumors are characterized by the presence of the above noted physaliphorous cells which are very rich in mucin and glycogen. These cells are distributed in cords of irregular lobules embedded in a matrix of reticular fibers and an amorphous intercellular substance that contains chondroitin sulfate, hyaluronic acid and keratin sulfate[4]. Morphologically, chordomas are similar to chondrosarcomas which, however, lack the physaliphorous cells, and some older studies without the help of immunohistochemical analysis may have inadvertently lumped these distinct entities together.

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice and radiation therapy is often used as supplemental treatment. However, since the extent of tumor resection is difficult to ascertain, and the use of terms such as local failure and disease free survival are difficult to standardize, it is difficult to interpret the results of the small series of treated patients[5]. Recently, encouraging results have been obtained with tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib. However, a detailed discussion of the therapeutic options is beyond the scope of this report, and the interested reader is referred to a recent review published in 2007[6].

The notion that chordomas are slow growing tumors requires qualification. As Crockard et al pointed out[5], some chordomas grow fast and there appears to be a good correlation between the rate of tumor growth and prognosis. In their study of skull-base chordomas, 24 patients were followed prospectively by serial MRIs after the initial surgery to evaluate the regrowth rates. The data was correlated with histological features and Ki67 labeling index as a measure of proliferation. Volume doubling times and labeling index showed a close correlation although most of the cases clustered around volumetric doubling-time of around 25 mo. It is not clear whether growth rate of recurrent tumors is the same as the growth rate of untreated tumors, and whether growth rate of the larger sacro-coccygeal tumors is different from that of tumors at the skull-base, which become symptomatic earlier. Our patient had a volumetric doubling time of 18.3 mo which is within the expected range based on the data presented by Crockard et al[5].

Controversy exists as to the best approach for biopsy, since several published reviews state that transrectal and transmural biopsies may incur a risk of tumor tract seeding and poor outcomes. This demands a more in-depth evaluation. Needle tract seeding with tumor is rare but well described for prostate cancer. A Medline search of “chordoma-tract (or track) seeding” produced no results. The same search using the Google internet search engine retrieved as a first hit a review in a family practice journal entitled “What was this retrorectal tumor?” The hyperlink referred to the full article[7] where a box with a red “Key Point” label stated: “A preoperative biopsy should not be performed with a retrorectal mass because of the risks of biopsy tract seeding and infection.” Two references are cited to support this advice. One of the two (a review by Fourney and Gokaslan[8]) refers to another review (Samson et al[9]) as the sole supporting evidence that transrectal biopsies should not be done. We will revisit the Samson paper shortly. The other cited source[10] is a 22 years old review which stated the following: “Of our 30 patients with chordomas, 16 received a curable resection. Nine had preoperative transrectal or trans-sacral biopsies. Recurrent tumors, including four instances of distant metastasis, subsequently developed in six of these patients. Seven patients in whom biopsy was not done received total resection, and only one patient had a recurrent tumor. In addition to recurrence, there were three complications after biopsy: two rectal abscesses and one fecal fistula. A biopsy has no role in diagnosis of retrorectal tumors unless the tumor is unresectable or highly likely to be metastatic.” Clearly, rectal biopsies or biopsies of any sort should not be done if they are followed by abscess or fistula formation in 33 percent of the cases. However, this is hardly the current experience. No causality between biopsies and poor outcomes has been established. We should also note that the authors do not discuss about the need to resect the rectum, they just observed the fact that the cases which had undergone the type of transrectal biopsy available at the time were more likely to be associated with recurrent disease in their study. No statistical tests were done. If we apply Fisher’s exact test to their data, which is appropriate here, these differences were not significant (P = 0.0514).

Interestingly, Fourney and Goskalan[8] state in their review that fine needle aspiration cytology should be done in almost all cases but not through the rectum or vagina. The single supporting reference for this statement is a paper summarizing the experience with sacro-coocygeal chordomas over a 20 years period at the Massachusetts General Hospital from 1972 to 1992 by Samson et al[9]. The authors of this older series state that “in three patients the rectum and anus were included in the resection after a diverting colostomy had been performed. In two of these patients the procedure was necessary because a transrectal biopsy had been performed, which Mindell has stated to be inappropriate.” The only other information we have is that these two cases had been referred to the authors for further management. The conclusion that transrectal biopsies were the culprit was probably the opinion of the attending physician abstracted from the chart or the opinion of the reviewers. Could this be referral bias and attribution bias? Readers will note that in one of the three cases, colostomy was necessary and no transrectal biopsy had been performed. To conclude from this limited data that transrectal biopsies lead to poor outcome appears unsound. We also do not know whether or not these biopsies were cutting (core) needle biopsies or FNA biopsies, guided by ultrasound. In the 1970’s, transrectal biopsies were often carried out with digital guidance[11]. Mindell stated more than 25 years ago[4]: “For instance, the biopsy should not be done through the rectum, or complete removal may necessitate resection of the rectum” but the author provided no cases or references to illustrate this belief. That the author is discussing about core biopsies rather than FNA cytology can be inferred from the following passage in the same paragraph: “Occasionally needle biopsy through a direct posterior route is satisfactory if both the surgeon and the pathologist are familiar with the techniques of obtaining adequate specimens through a needle and of preparing small plugs of tissue for histological examination”.

We believe that we have shown that there is no convincing data that transrectal biopsies of chordomas, especially if performed under real-time ultrasound guidance, are inherently more risky than transrectal biopsies of, for example, prostate cancer. There are several reports of recurrence of prostate carcinoma in the submucosa of the rectum along the needle tract as evidenced by the presence of small nodules or micrometastases observed at surgery for other reasons[12], but the overall risk of this is extremely small. It is hard to conceive that this should be any worse in tumors which grow much more slowly than even prostate cancer. Transrectal FNA biopsies may actually have a theoretical advantage since the needle tract is typically the shortest.

We believe that biopsy of a suspected chordoma is essential. If a chordoma is found the patient should be encouraged to seek treatment at a referral center where relevant experience exists. Of all the biopsy modalities available, transrectal FNA biopsy under ultrasound guidance seems to offer the best risk-benefit ratio.

| 1. | McMaster ML, Goldstein AM, Bromley CM, Ishibe N, Parry DM. Chordoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1973-1995. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12:1-11. |

| 2. | Yamaguchi T, Watanabe-Ishiiwa H, Suzuki S, Igarashi Y, Ueda Y. Incipient chordoma: a report of two cases of early-stage chordoma arising from benign notochordal cell tumors. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1005-1010. |

| 3. | Munday JS, Brown CA, Richey LJ. Suspected metastatic coccygeal chordoma in a ferret (Mustela putorius furo). J Vet Diagn Invest. 2004;16:454-458. |

| 4. | Mindell ER. Chordoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:501-505. |

| 5. | Crockard HA, Steel T, Plowman N, Singh A, Crossman J, Revesz T, Holton JL, Cheeseman A. A multidisciplinary team approach to skull base chordomas. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:175-183. |

| 6. | Casali PG, Stacchiotti S, Sangalli C, Olmi P, Gronchi A. Chordoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:367-370. |

| 7. | Silverman AT, Parker GS, Lake TR, Saad SA. What was this retrorectal tumor? J Fam Pract. 2006;62 Available from: URL: http://www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=4136. |

| 8. | Fourney DR, Gokaslan ZL. Current management of sacral chordoma. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E9. |

| 9. | Samson IR, Springfield DS, Suit HD, Mankin HJ. Operative treatment of sacrococcygeal chordoma. A review of twenty-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1476-1484. |

| 10. | Jao SW, Beart RW Jr, Spencer RJ, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM. Retrorectal tumors. Mayo Clinic experience, 1960-1979. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:644-652. |