INTRODUCTION

Ghrelin is a 28-amino acid peptide that is synthesized in endocrine cells of the gastric mucosa[1]. The major actions of this recently-discovered peptide include stimulation of growth hormone (GH) release[1–3], regulation of appetite and nutrient ingestion[4–6], and improvement of digestive motility[7–9]. When injected into mice[710], rats[89], or dogs[11], ghrelin accelerates gastric emptying after a liquid or solid meal. In vitro studies showed that in addition to known vagus nerve-dependent mechanisms, the activity of ghrelin is mediated via the enteric nervous system. Ghrelin increases electrically evoked cholinergic neural responses in strips of rat stomach[1213]. The presence of ghrelin and its receptors has been proven morphologically for myenteric neurons of guinea pig stomach and ileum[14], but ghrelin receptors are difficult to identify on smooth muscles[15].

Delayed gastrointestinal transit is a well-known diabetic complication, and may lead to uncomfortable gastrointestinal symptoms, such as frequent vomiting, emaciation, and unpredictable changes in blood glucose, all of which impair the quality of life of diabetic patients[1617]. Gastrointestinal transit of solid or nutrient liquid meals is abnormally slow in about 50% of diabetic patients[16]. Delayed gastrointestinal transit may be associated with cardiac autonomic neuropathy, blood glucose concentration, and gastrointestinal symptoms[16].

Ghrelin has also been shown to accelerate gastric emptying in animal models of postoperative ileus[18], septic ileus[10], and burn-induced slow gastrointestinal transit[19]. Ghrelin injections accelerate gastric emptying after a meal in humans even in the presence of deficient gastric innervation[20]. However, ghrelin has never been studied in a diabetic animal model. It is unknown whether ghrelin can exert a similar prokinetic effect on the impaired gastrointestinal motility of diabetic mice, thus potentially having a clinical role in the treatment of impaired gastrointestinal motility in diabetic patients. In the present study, alloxan-induced diabetic mice were selected as an animal model of diabetic gastroparesis, resulting from autonomic neuropathy injury induced by prolonged hyperglycemia. We tested the effect of this newly-discovered gastric peptide on delayed gastrointestinal transit in diabetic mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Rat ghrelin was obtained from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). Atropine sulphate, phenol red, and alloxan were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Diabetic mouse model

C57 mice (weighing 18-22 g) were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Shanghai Academia Sinica. All procedures for the animal experiments were approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of Shanghai Jiaotong University. The mice were housed in stainless steel cages at a controlled temperature (22 ± 2°C) with a 60%-65% relative humidity in a normal 12-h light and dark cycle. After exposure to a high-fat diet for 3 wk, the mice were fasted overnight with free access to water and injected intraperitoneally with alloxan (0.2 g/kg body weight) dissolved in a sterile normal saline solution. Seventy-two hours later, the fasting blood glucose level in the mice was determined using the glucose oxidase method on a glucose analyzer. Mice with a blood glucose level higher than 11.1 mmol/L were classified as diabetic mice (DM mice). The DM mice were continuously fed without control of blood glucose for 4 wk, and a model of DM mice was established for further investigations.

Animal grouping for gastrointestinal transit studies

Gastric emptying, intestinal and colonic transit studies were then performed. In each study, mice were divided into two groups: a normal (control) group and a diabetic group. Mice in the diabetic group were treated with different doses of ghrelin (0, 20, 50, 100 and 200 &mgr;g/kg) given in a random order with a total of six mice in each subgroup. A dose-response curve for ghrelin was obtained for the experiment. Based on the most effective dose of ghrelin, another group of 6 mice was given atropine (1 mg/kg) injections 15 min before ghrelin injection.

Gastric emptying

After a 12-h fast, the diabetic mice were injected with different doses of ghrelin (0, 20, 50, 100 and 200 &mgr;g/kg). After ghrelin injection, the mice received a gavage feeding (5 mg/kg body weight) of a phenol red test meal (0.5 g/L in 0.9% NaCl with 1.5% methylcellulose). Twenty minutes later, the mice were sacrificed. Their stomachs were clamped with a string above the lower oesophageal sphincter and a string beneath the pylorus to prevent leakage of phenol red. Gastric emptying was determined spectrophotometrically, according to the method previously described with certain slight modifications. The stomach of each individual mouse was resected just above the lower oesophageal sphincter and pyloric sphincter. Phenol red remained partly in the lumen of the stomach. The stomach and its contents were put into 5 mL of 0.1 mol/L NaOH. The stomach was minced. The samples containing the total amount of phenol red present in the stomach were further diluted to 10 mL with 0.1 mol/L NaOH and left at room temperature for 1 h. Five milliliters of the supernatant was then centrifuged at 800 g for 20 min. The absorbance was read at a wavelength of 546 nm on a spectrophotometer (Shanghai Yixian Company, China), and the phenol red content in the stomach was calculated. Percentage of gastric emptying of the phenol red was calculated as [infusion amount-remains]/infusion amount] × 100%.

Intestinal and colonic transit

After an overnight fast, mice were given general anesthesia (2%-3% isoflurane inhalation) and underwent abdominal surgery. A small polyethylene tube was placed in the duodenum (or colon) via the stomach (or cecum), 0.5 cm distal to the pylorus (or ileocolic junction), fixed with sutures to the gut wall, and then tunneled through the abdominal wall subcutaneously to exit from the skin at the nape of the neck. Midline incisions were sutured, and mice were left to recover in separate cages. Food and water were abundantly provided. Three days later, after a-12 h fast, the mice were given different doses of ghrelin (0, 20, 50, 100 and 200 &mgr;g/kg) intraperitoneally. After ghrelin injection, a phenol red test meal at 5 mg/kg (0.5 g/L in 0.9% NaCl with 1.5% methylcellulose) was injected into the duodenum (or colon) via the implanted polyethylene tube. After 20 min, the mice were sacrificed. The distance of phenol red transit and the full length of the intestine or colon were calculated. Small intestine or colonic transit was assessed using the percentage ratio of phenol red transit over the full intestinal or colonic length.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was conducted using one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. Data are expressed as mean ± SE. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Gastric emptying and intestinal and colonic transit in diabetic mice

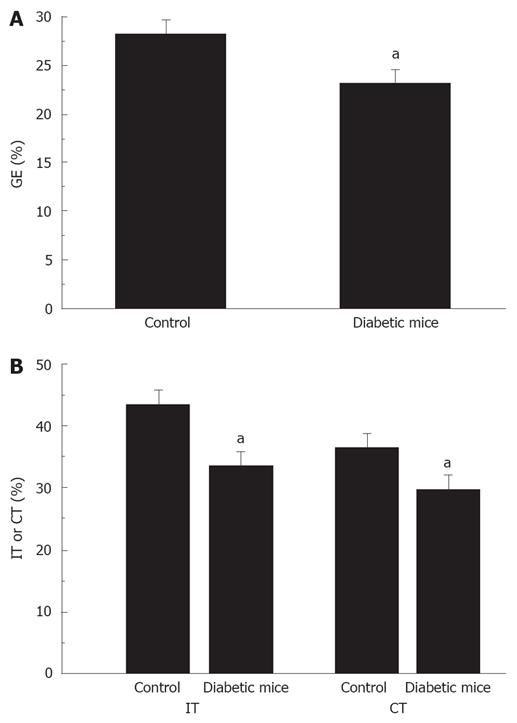

Significantly delayed gastric emptying, intestinal and colonic transits were found in diabetic mice. Gastric emptying was significantly decreased in diabetic mice compared to normal mice (22.9% ± 1.4% vs 28.1% ± 1.3%, P < 0.05, Figure 1A). Also, intestinal transit was significantly decreased in diabetic mice compared to normal mice (33.5% ± 1.2% vs 43.2% ± 1.9%, P < 0.05, Figure 1B). In addition, colonic transit was also decreased in diabetic mice compared to normal mice (29.5% ± 1.9% vs 36.3% ± 1.6%, P < 0.05, Figure 1B).

Figure 1 Delayed gastric emptying and intestinal and colonic transit in diabetic mice.

A: Percentage of gastric emptying was significantly decreased in diabetic mice, aP < 0.05 vs control; B: Percentage of intestinal and colonic transits was significantly decreased in diabetic mice, aP < 0.05 vs control.

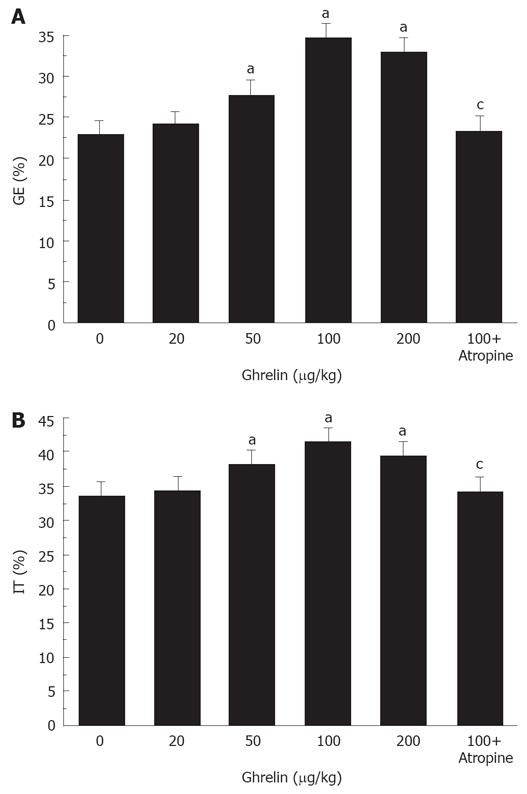

Effect of ghrelin on delayed gastric emptying in diabetic mice

Ghrelin significantly accelerated gastric emptying in diabetic mice. The percentage of gastric emptying was 24.3% ± 2.1%, 27.8% ± 1.0%, 34.5% ± 1.2%, and 32.9% ± 1.1%, respectively, in the mice treated with 20, 50, 100, and 200 &mgr;g/kg ghrelin. Except for the lowest dose, all of these doses normalized the rate of gastric emptying in diabetic mice (P < 0.05, Figure 2A). We considered that 100 &mgr;g/kg ghrelin could most effectively increase the rate of gastric emptying.

Figure 2 Ghrelin significantly increases gastric emptying (A) and intestinal transit (B) in diabetic mice.

aP < 0.05 vs control, cP < 0.05 vs 100 &mgr;g/kg ghrelin.

Effect of ghrelin on delayed small intestinal transit in diabetic mice

Ghrelin significantly accelerated intestinal transit in diabetic mice. The percentage of intestinal transit was 34.6% ± 2.0%, 38.2% ± 1.6%, 41.5% ± 1.9%, and 39.5% ± 1.8%, respectively, in the mice treated with 20, 50,100, and 200 &mgr;g/kg ghrelin. All of these doses except for 20 &mgr;g/kg normalized the delayed intestinal transit (P < 0.05, Figure 2B). As above, 100 &mgr;g/kg ghrelin was considered most effective in accelerating intestinal transit.

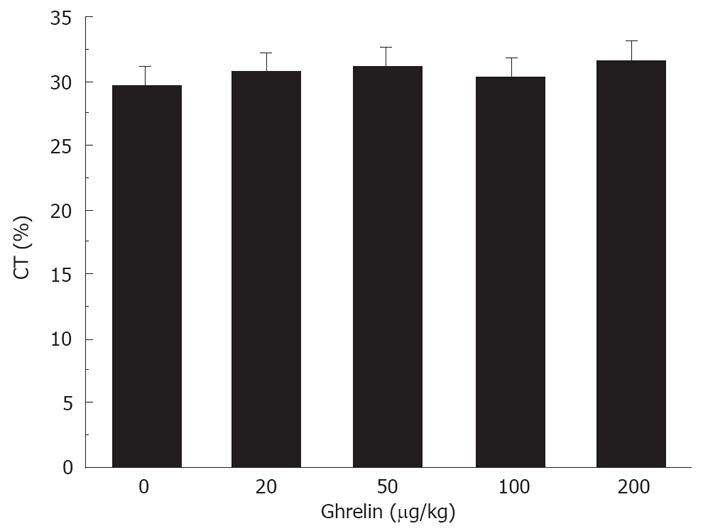

Effect of ghrelin on delayed colonic transit in diabetic mice

Ghrelin had no effect on delayed colonic transit. The percentage of colonic transit was 30.6% ± 1.3%, 30.2% ± 1.8%, 29.2% ± 1.5%, and 31.6% ± 2.2%, respectively, in the mice treated with 20, 50, 100, and 200 &mgr;g/kg ghrelin. None of these doses was able to accelerate intestinal transit (Figure 3).

Figure 3 No effect of Ghrelin on delayed colonic transit in diabetic mice.

Effect of atropine on delayed gastric emptying and intestinal transit in diabetic mice

Atropine blocked the positive effect of 100 &mgr;g/kg ghrelin on gastric emptying and intestinal transit. The percentage of gastric emptying was significantly decreased from 34.5% ± 1.2% to 23.5% ± 1.7% (P < 0.05, Figure 2A). The small intestine transit was significantly decreased from 41.5% ± 1.9% to 34.2% ± 1.6% (P < 0.05, Figure 2B).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, mice with alloxan-induced diabetics had mild or moderate gastroparesis with slow gastric emptying and intestinal transit due to an autonomic neuropathic injury induced by prolonged hyperglycemia as compared with normal controls. Thus, mice with alloxan-induced diabetics could be used as an animal model of diabetic gastroparesis. Significantly delayed gastric emptying, intestinal and colonic transit were seen in the mice with alloxan-induced diabetics. Different doses of ghrelin were able to accelerate gastric emptying and intestinal transit in the diabetic mice, but had no effect on colonic transit. The most effective dose of ghrelin for accelerating upper gastrointestinal transit was 100 &mgr;g/kg per mouse. Atropine blocked the ghrelin effect on gastric emptying and intestinal transit.

In the present study, gastric emptying and intestinal and colonic transit were significantly delayed in the mice with alloxan-induced diabetics, which is consistent with the previously reported findings[2122]. Gastrointestinal motility disturbances including esophageal motor dysfunction, gastroparesis, constipation and diarrhea, are common in patients with diabetes mellitus. It was reported that gastrointestinal transit is significantly slower in the diabetic animal model of human diabetes[21–23]. Inhibition of gastrointestinal motility has also been reported in humans with diabetes mellitus[2425]. The pathogenesis of slow gastrointestinal transit in diabetes mellitus patients is not clear, but several mechanisms have been proposed[16]. Among them, autonomic neuropathy, a complication of long-standing diabetes mellitus, has been widely accepted as the culprit. This may lead to the absence of postprandial gastrointestinal response, a reflex that should present in healthy people[24]. Recent studies have shown that an acute change in blood glucose concentration also has a major effect on gastrointestinal motor function in healthy subjects[25]. In particular, acute hyperglycemia inhibits both the gastrointestinal and ascending components of peristaltic reflex. Poor glycemic control has the potential to cause delayed gastrointestinal transit in diabetic patients[26].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the effect of ghrelin on gastrointestinal dysmotility in diabetic mice. Ghrelin possessing prokinetic characteristics increases gastric emptying in healthy mice[2728], gastric emptying[132930], frequency of migrating motor complex, and intestinal transit[3132] in healthy rats. In healthy dogs, ghrelin stimulates antral contractility and antroduodenal coordination, thus increasing gastric emptying[33]. In healthy volunteers[29], subjects with normal weight[34], and gastroparetic[35] human subjects with gastroparesis, ghrelin also increases gastric emptying. The mechanisms underlying the action of ghrelin seem to be neuron-dependent. In vitro, isolated strips of muscle fail to contract significantly when exposed to ghrelin. In vivo, the gastrokinetic effect of ghrelin in rats is abolished by atropine and vagotomy. Diabetic gastroparesis is classically attributed to autonomic neuropathy induced by prolonged hyperglycemia, which did not preclude the gastrokinetic effect of ghrelin in our investigation. Our data strongly suggest that ghrelin can exert a prokinetic action on the upper alimentary tract via the enteric nervous pathway. In our study, atropine blocked the effect of 100 &mgr;g/kg ghrelin on gastric emptying and intestinal transit, suggesting that the prokinetic effect of ghrelin is mediated via the cholinergic pathway in the enteric nervous system. There are other mechanisms involving tachykininergic pathways, as demonstrated in electrical field stimulation studies in isolated rat stomach[13].

Moreover, we found that the dose-response relationships of ghrelin between gastric emptying and colonic transit in diabetic mice were bell-shaped. There are many causes for bell-shaped dose-response curves. Desensitization is one of the possibilities, because ghrelin receptor is susceptible to rapid desensitization[36]. Another possibility is the existence of high and low affinity receptor binding sites in different pathways. In our study, however, ghrelin showed no effect on colon transit, which is consistent with the results seen both in animal models of postoperative ileus[18] and in burn-induced gastrointestinal delayed transit[19]. We believe that this result might be related to the distribution of ghrelin receptors in the gut[3738].

Based on this study, it is reasonable to assume that ghrelin can be used as a potential drug for the treatment of diabetic patents with delayed gastrointestinal transit. Clinically, improvement in gastrointestinal transit facilitates enteral resuscitation, corrects blood glucose concentrations and reduces gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetic patients.

In conclusion, ghrelin accelerates gastric emptying and intestinal transit in diabetic mice, an action that may be mediated via the cholinergic pathway in the enteric nerve system. Ghrelin may have a therapeutic potential for diabetic patients with delayed upper gastrointestinal transit. The physiological role of ghrelin in the gastrointestinal tract remains to be identified, and its pharmacotherapeutic potential deserves to be further explored in diabetic patients suffering from delayed upper gastrointestinal transit.

COMMENTS

Background

Delayed gastrointestinal transit is common in patients with chronic diabetes and is always associated with impairments in quality of life and diabetic control. Ghrelin is a potent prokinetic peptide. The effect of ghrelin on delayed gastrointestinal transit was studied in diabetic mice.

Research frontiers

The effects of ghrelin on gastrointestinal motor activity and roles in motility regulation have been extensively studied. This study is the first to investigate the effects of ghrelin on diabetic mice with delayed gastrointestinal transit.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Ghrelin has been shown to accelerate gastric activity in postoperative and septic ileus animal models. However, it has not been studied in a diabetic animal model.

Applications

According to animal experiments, ghrelin may be used as a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of delayed gastrointestinal transit in diabetes.

Peer review

This paper shows for the first time that ghrelin has an effect on gastric emptying and intestinal transit in diabetic mice, which may be mediated through the cholinergic pathways in the enteric nerve system. These results show that ghrelin can be used as a potential therapeutic drug for the treatment of delayed gastrointestinal transit in diabetes.