INTRODUCTION

Ischemic colitis is the most common ischemic injury of the gastrointestinal tract. Although it can occur at any age, approximately 90% of the patients were over 60 years of age[1]. It is usually self-limited and is often called transient ischemic colitis.

We encountered a 41-year-old male patient, who presented with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea, and had been diagnosed as having ulcerative colitis. The colonoscopy showed ulcerative colitis, but the rectum was spared from inflammation. Corticosteroids did not relieve the disease, but aggravated the symptoms. On an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan and CT angiography, the mesenteric and splenic veins were absent with numerous venous collaterals for drainage. The final diagnosis was ischemic colitis with obstruction of the mesenteric and splenic veins. In this report, we describe this unusual case of ischemic colitis caused by chronic venous insufficiency.

CASE REPORT

A 41-year-old man, a Bangladeshi migrant worker in Korea, was admitted to our hospital with a three-year history of lower abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. He was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, treated with oral corticosteroids in an outside clinic, and referred to our facility for further evaluation. The physical examination was remarkable for lower abdominal tenderness without rebound. A routine blood analysis revealed a slightly decreased level of hemoglobin (109 g/L), hematocrit (33.8%), white cell count (14.12 × 109/L) and platelets (106 × 109/L). Urea and electrolytes, glucose, amylase and liver function were normal but the patient had a slightly raised level of C-reactive protein (6.7 mg/L). The patient was presumed to have ulcerative colitis with moderate to severe activity and was treated with corticosteroids. After 48 hours, he underwent a flexible sigmoidoscopy, which showed a 3-cm sized deep ulceration at the rectosigmoid junction, and friable mucosa in a diffuse circumferential distribution. Severe colitis with superimposed infection was suspected because of mild fever, and antibiotic treatment was added. Blood and stool cultures were negative. There was a minimal improvement in the clinical course, but his symptoms were not totally alleviated. Two weeks after admission, a colonoscopy was performed to evaluate the extent and other causes of the disease. It demonstrated colitis with markedly edematous mucosa and tortuous and dilated veins throughout the colon, but the rectal mucosa was spared from inflammation. The fine granularity of the mucosa was associated with friability, and contact bleeding with mucus was observed (Figure 1A-D). The biopsy specimens obtained from the edematous colonic mucosa and the ulcer of the rectosigmoid junction showed nonspecific chronic inflammation.

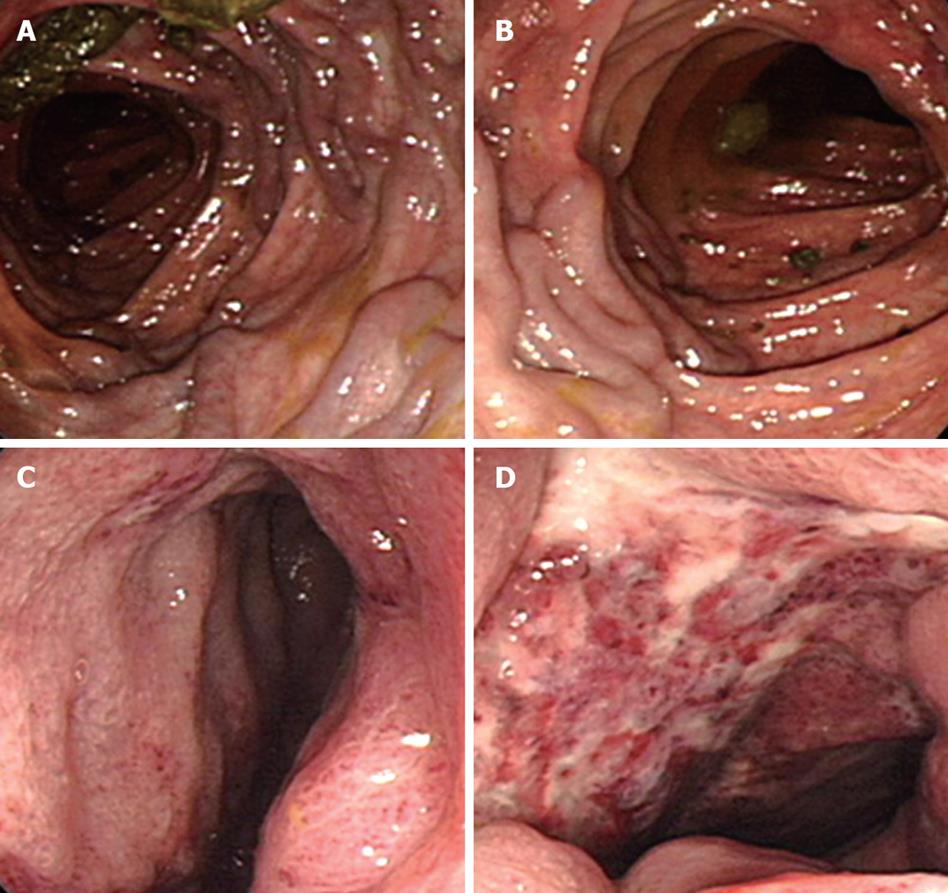

Figure 1 Colonoscopic findings.

A, B: Tortuous and dilated submucosal veins in the colonic mucosa; C: Diffuse and edematous mucosa with fine granularity resembling ulcerative colitis; D: A deep ulceration at rectosigmoid junction.

A dynamic abdominal CT was performed. On arterial phase CT, diffuse edematous thickening of the colon with dilated and tortuous peripheral branches of colic arteries was seen. The rectosigmoid colon appeared markedly thickened. Major abdominal arteries including the celiac axis, splenic artery, superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) were all normal in size and shape. However, on venous phase CT, the splenic vein, superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) were absent. Dilated and tortuous peripheral colic veins drained into the portal vein via tortuously dilated intraperitoneal collaterals (Figures 2A and B, and 3A-C). Venous blood of gastrointestinal tract and spleen drained into the portal vein via various routes of the collateral venous pathway that are similar to the intra-abdominal venous collaterals in patients with portal hypertension. The main collateral venous routes in our patient were pericolic and mesenteric collaterals, splenic hilar and perigastric collateral-pancreaticoduodenal collaterals-the portal vein. Some venous drainage of the lower portion of the left colon drained into the left renal vein via the left gonadal vein. In addition, the venous collaterals of the rectosigmoid colon drained into the bilateral internal iliac veins. The patient refused angiographic evaluation for the anomalous abdominal venous system.

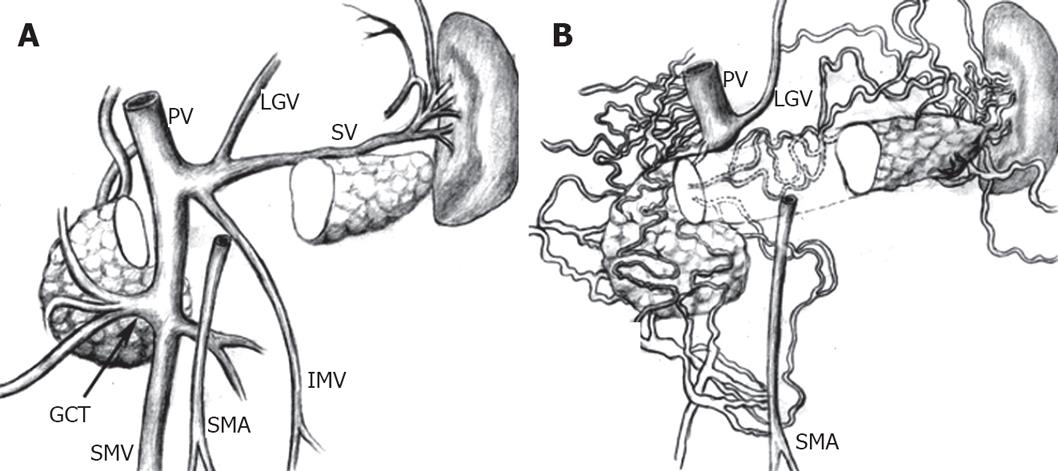

Figure 2 Dynamic abdominal CT.

A: The normal anatomy of the main portal vein and its tributaries including the portal vein (PV), left gastric vein (LGV), gastrocolic trunk (GCT), splenic vein (SV), SMA, SMV, and IMV are schematically illustrated; B: The normal mesenteric vein (SMV and IMV) and splenic vein are absent. Numerous collateral venous channels developed to drain venous blood from gastrointestinal tract to portal vein.

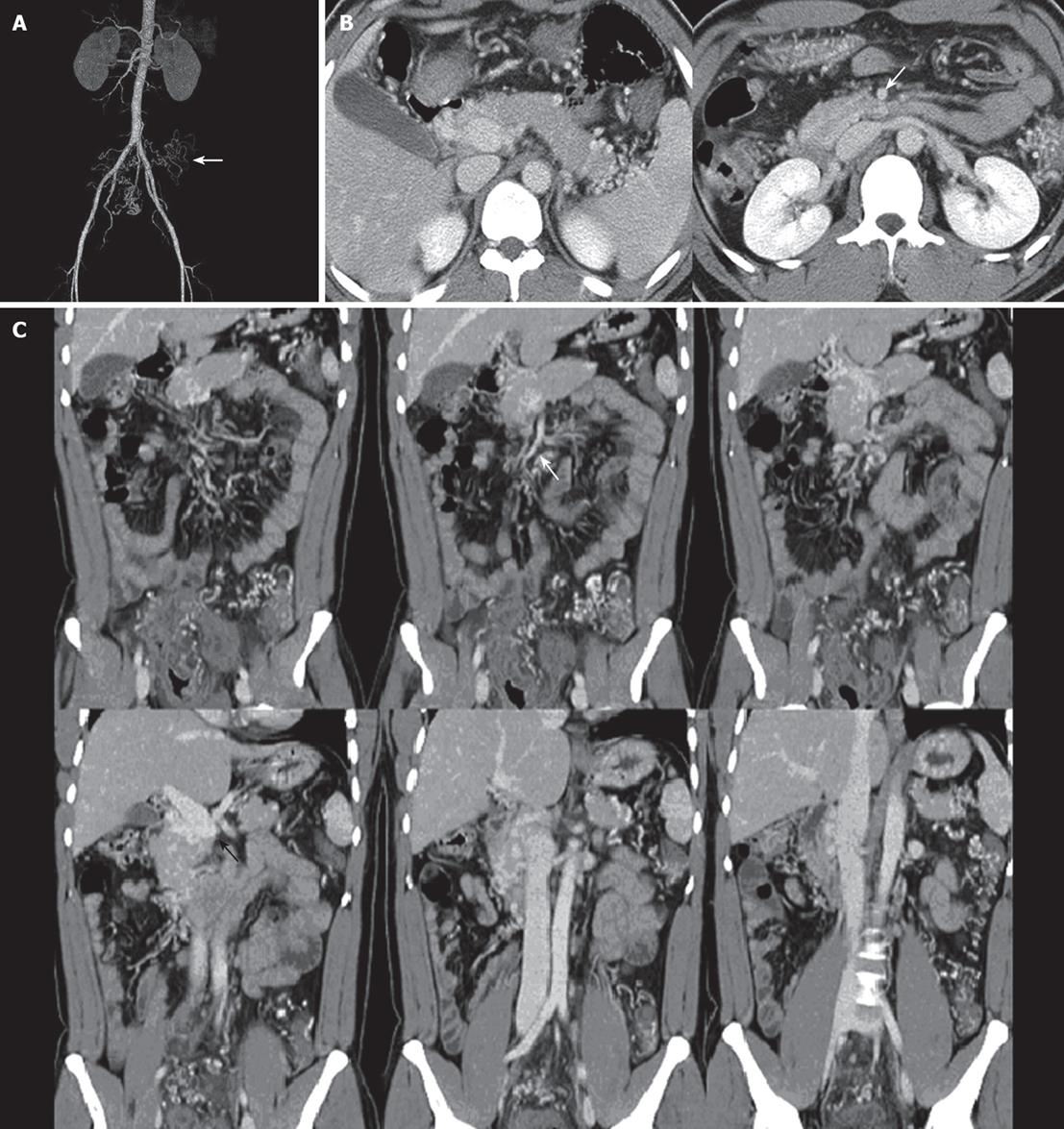

Figure 3 Abdominal CT arteriography.

A: Normal shape and course of SMA, IMA, and splenic artery, tortuous and dilated distal branches of SMA and IMA around rectosigmoid colon; B: An axial and C: Coronal reformatted abdominal CT reveal the absent splenic vein, SMV, and IMV with numerous intra- and peripancreatic collaterals. Distal end portal vein is abruptly ended (black arrow) and SMA is normal (white arrow). Note prominent dilated pericolic arteries and venous collaterals, and markedly

thickened sigmoid colon.

The final diagnosis was ischemic colitis with obstruction of the mesenteric and splenic veins. Corticosteroids did not relieve the disease, but aggravated the symptoms. The patient discontinued steroid therapy and gradually responded to oral aminosalicylates. After nine months, he was in remission and re-evaluated by sigmoidoscopy. It showed some improvement of the colonic inflammation and a complete resolution of the ulcer in the rectosigmoid area.

DISCUSSION

Ischemic colitis is a well-recognized clinical phenomenon, although its precise etiology remains unclear. It may manifest a spectrum of severity from mild, transient mucosal erosion to fibrous scarring with stricture formation and even transmural infarction. Some cases are caused by acute macrovascular mesenteric occlusion due to surgical trauma[2], thromboembolism[3–5], or atherosclerosis[6]. However, chronic venous insufficiency is rarely associated with ischemic colitis. Ischemic colitis typically develops spontaneously without signs of major vascular occlusion, and viable intestine is present elsewhere in the tract. Isolated case reports have described development of ischemic colitis in conjunction with mild allergy, hypertension, rectal prolapse, acute pancreatitis, sickle cell crisis, colon cancer, systemic lupus erythematosus, amyloidosis, anticardiolipin antibody syndrome, Buerger’s disease, and Kawasaki syndrome[7–9]. Other case reports described the association between development of ischemic colitis and use of some agents (progesterone, ergotamine derivatives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and danazol)[10], intravenous vasopressin therapy[11], renal transplantation[12], chronic intermittent peritoneal dialysis[13], cocaine abuse, snake bite and marathon running[7].

Clinical presentation is usually acute, with cramping abdominal pain of abrupt onset, abdominal distention, and bloody diarrhea. There may be local signs of peritoneal irritation over the affected segment, and if mucosal ulceration is present, bacterial invasion may also occur. However, manifestations vary widely, from severe pain with transmural infarction and early perforation to mild abdominal pain and only slight tenderness[14].

It is extremely difficult to differentiate ischemic from ulcerative colitis. Moreover, ischemic and idiopathic ulcerative colitis may coexist[15]. An endoscopic finding of ulcerative colitis is characterized by a uniform inflammatory reaction in the colonic mucosa, without intervening areas of normal mucosa. The majority of cases arise in the rectum, and some authorities believe that the rectum is always involved in an untreated patient[16]. With inflammation, the mucosa becomes erythematous and granular, and the vascular pattern becomes obscured by edema. In this patient, a similar pattern of mucosal lesions was observed as mentioned above. However, while making the diagnosis as ulcerative colitis, we found that (1) the rectal mucosa was free from inflammatory reaction; (2) although the patient did not have a fulminant clinical course, a deep ulceration was observed; and (3) the disease was resistant to corticosteroid therapy and instead aggravated his clinical course. Color Doppler scans were used to differentiate the bowel-wall thickening in ischemic colitis from that seen in inflammatory bowel disease[7].

Generally, major arterial or venous branches are easily detected on arterial or venous phase CT. The SMV is located anteriorly and to the right of the SMA and posteriorly medial to the head of the pancreas. The SMV tributaries are the ileocolonic, pancreatoduodenal, and gastroepiploic veins. The IMV originates anterior to the sacrum as the superior rectal (hemorrhoidal) vein and receives branches from the sigmoid and descending colon as it ascends to the left of midline, adjacent to the inferior mesenteric artery and left gonadal vein. In the upper abdomen, the IMV passes from posterior to the distal duodenum, anterior to the left renal vein, and then anterior to the SMA before anastomosing with the portal venous system. The splenic vein is easily detected beneath the pancreas and drains to the portal vein[17]. In this patient, the proximal SMV, IMV and most of splenic vein were absent despite the presence of a normal SMA and IMA and splenic artery. The tortuous and dilated distal branches of SMA and IMA around the entire colon were seen on arterial phase CT and no remarkable SMV and IMV were noted on venous phase CT except for the prominent collateral veins. Instead of a normal splenic vein beneath the pancreas, tortuous splenic hilar venous collaterals developed and drained into the portal vein via the peripancreatic venous collaterals. Although we have no direct angiographic evidence, the anomaly described in this report appears unique. We presume the congenital absence of the SMV, IMV, and splenic vein results from excessive involution of proximal vitelline veins.

In this case, the arterial blood supply and venous drainage might have been balanced for a long time because of numerous abdominal venous collaterals. In addition, a possible breakage of this balance may cause venous stasis and ischemia of the gastrointestinal tract. Impaired colonic venous drainage may be a possible cause or vulnerable to the development of ischemic colitis. The relationship between the absence of mesenteric veins with possible venous stasis and ischemic colitis is not clearly established. Although the patient is currently doing well after medical and conservative treatment, a long-term follow-up is needed as there is little information in the literature regarding the outcome of the absence of the proximal mesenteric veins and its influence upon venous drainage.