Published online Apr 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2044

Revised: January 28, 2008

Published online: April 7, 2008

AIM: To determine factors predictive for esophageal varices in severe alcoholic disease (SAD).

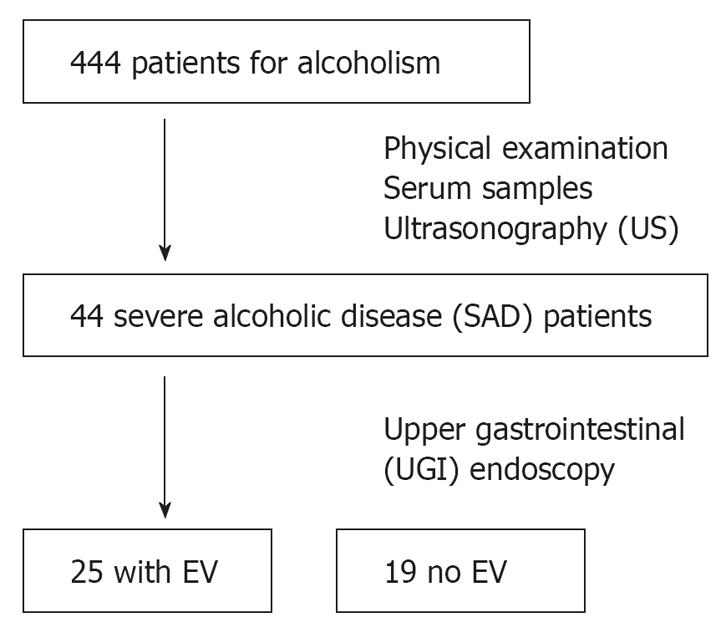

METHODS: Abdominal ultrasonography (US) was performed on 444 patients suffering from alcoholism. Forty-four patients found to have splenomegaly and/or withering of the right liver lobe were defined as those with SAD. SAD patients were examined by upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopy for the presence of esophageal varices. The existence of esophageal varices was then related to clinical variables.

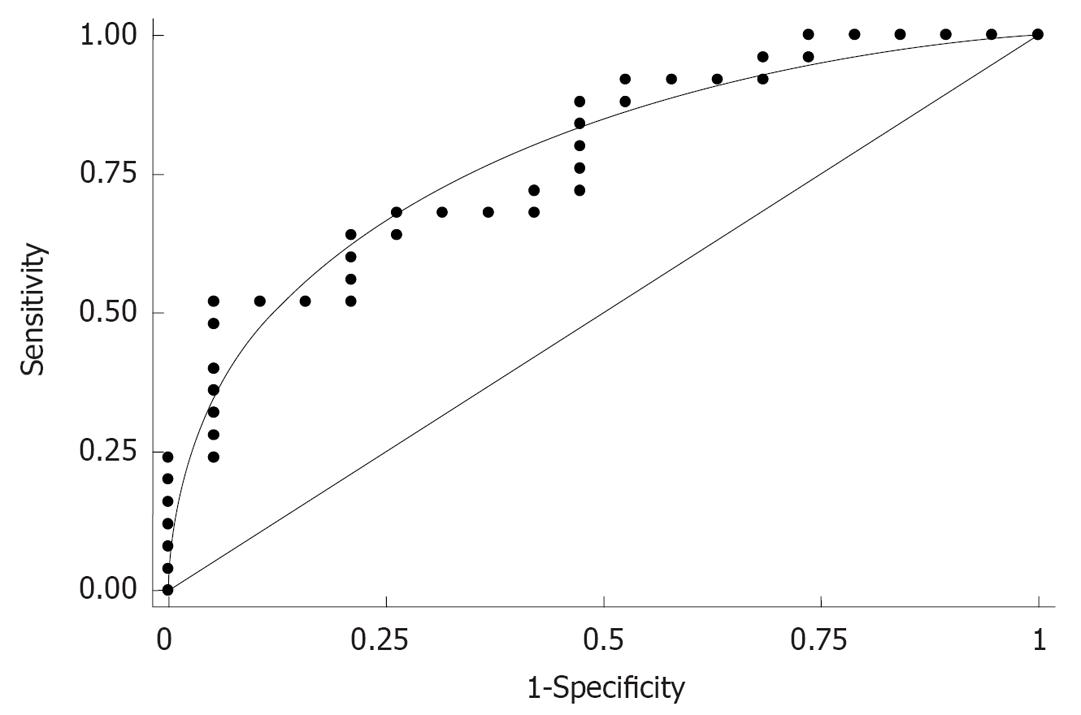

RESULTS: Twenty-five patients (56.8%) had esophageal varices. A univariate analysis revealed a significant difference in age and type IV collagen levels between patients with and without esophageal varices. A logistic regression analysis identified type IV collagen as the only independent variable predictive for esophageal varices (P = 0.017). The area under the curve (AUC) for type IV collagen as determined by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) for predicting esophageal varices was 0.78.

CONCLUSION: This study suggests that the level of type IV collagen has a high diagnostic accuracy for the detection of esophageal varices in SAD.

- Citation: Mamori S, Searashi Y, Matsushima M, Hashimoto K, Uetake S, Matsudaira H, Ito S, Nakajima H, Tajiri H. Serum type IV collagen level is predictive for esophageal varices in patients with severe alcoholic disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(13): 2044-2048

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i13/2044.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.2044

Regular daily drinking is more likely to result in liver damage than intermittent drinking. The longer this pattern is maintained, the more likely it is that alcoholic hepatitis, and subsequently cirrhosis, will develop[1]. In patients with cirrhosis, the incidence of esophageal varices increases by nearly 5% per year, and the rate of progression from small to large varices is approximately 5%-10% per year[23]. Bleeding from esophageal varices is common among patients with cirrhosis. Bleeding from varices may occur in 15%-68% of patients with varices[4]. Variceal hemorrhaging is associated with a high mortality and with high hospital costs[5]. Both, beta-blockers and endoscopic procedures, have been established as effective preventive modalities for variceal hemorrhage[56]. Therefore, the early detection of esophageal varices is critical for the effective prevention of variceal hemorrhage[7]. Adding an accurate serum marker for hepatic fibrosis to the model may improve the diagnostic accuracy in predicting esophageal varices without performing liver biopsy. Moreover, developing an accurate non-invasive diagnostic model might also decrease the costs for the prevention of hemorrhaging from varices[7].

In daily medical practice, it is common to encounter patients with liver damage from chronic alcohol consump-tion. Moreover, when the alcoholic patient is examined, it is often evident that alcoholic liver damage is progressing. Once alcoholic cirrhosis is established, esophageal varices develop in the majority of patients, as found during prolonged follow-up[8]. Nevertheless, alcoholic patients tend to be indifferent regarding self health, and are not likely to undergo periodic consultations. We therefore examined predictive factors for esophageal varices in severe alcoholic disease.

The 444 consecutive patients considered for this study were hospitalized at the Tokyo Medical Center of Alcohol Related Disabilities in Tokyo, Japan, between April and September 2005, July 2006, and June 2007 for alcoholism.

A complete physical examination was performed by a senior physician. The recorded variables included age, gender, height, body weight, mean alcohol consumption, duration of alcohol abuse, jaundice, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy.

After an overnight fast, serum samples were obtained from all patients for test purposes, including a complete blood cell count, blood platelets, bilirubin, aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GTP), albumin, prothrombin index (ratio between patient and control Quick time expressed in percentage), and type IV collagen (Mitsubishi Chemical Medience Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Ultrasonography (US) was performed by experienced gastroenterologists during the stay in hospital. The spleen was visualized with the patient in the right lateral decubitus position. Measurements were then taken in the sagittal (S) and transverse (T) planes, with the maximum dimension being recorded in each plane[9]. Splenomegaly was defined as a spleen index (S × T × 0.9) > 30. Alcoholic patients with splenomegaly and/or withering of the right liver lobe were defined as severe alcoholic disease patients (SAD) and included into the study. Patients with the following criteria were excluded: (1) the presence of suspected hepatocellular carcinoma on US; (2) the presence of extra-hepatic infectious or inflammatory disease; (3) treatment by any drug known to affect liver fibrosis; (4) seropositivity for the hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C virus, and/or human autoimmune antibodies. Finally, we identified 44 SAD patients (Table 1).

| Esophageal varice | Yes (n = 25) | No (n = 19) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 49.6 ± 7.0 | 55.5 ± 9.2 | < 0.05 |

| Sex (male/female) | 20/5 | 15/4 | NS |

| Total alcohol intake (kg) | 1075.9 ± 646.9 | 1018.4 ± 684.9 | NS |

| MCV (fL) | 97.7 ± 12.4 | 95.9 ± 12.0 | NS |

| Plt (/&mgr;L) | 12.6 ± 6.1 | 13.9 ± 9.8 | NS |

| PT (%) | 62.6 ± 16.2 | 69.3 ± 18.8 | NS |

| AST (IU/L) | 80.9 ± 72.6 | 96.1 ± 85.1 | NS |

| ALT (IU/L) | 44.4 ± 2.6 | 45.2 ± 28.5 | NS |

| GTP (IU/L) | 453.6 ± 594 | 410.2 ± 374.3 | NS |

| T -Bil (mg/dL) | 2.7 ± 3.2 | 2.4 ± 1.9 | NS |

| Alb (g/dL) | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | NS |

| Collagen type IV (ng/mL) | 712.3 ± 355.6 | 404.3 ± 198 | < 0.001 |

| Ascites (yes/no) | 6/19 | 2/17 | NS |

| Encephalopathy (yes/no) | 1/24 | 2/17 | NS |

For each patient, upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopy was performed by an endoscopist. The purpose of endoscopy was to evaluate the presence of esophageal varices (Figure 1). The endoscopist evaluated esophageal varices with the Esophagogastric Varices Grading System of the Japan Society for Portal Hypertension[10]. The endoscopist performed UGI endoscopy without knowledge of serum data.

The results were expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences between the groups were examined for statistical signifi-cance using the Mann-Whitney U test and a χ2 test where appropriate. Independent predictive factors associated with esophageal varices were assessed by a multivariate analysis using a logistic regression model. The sensitivity and specificity of collagen type IV for predicting esophageal varices was determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the STATA 10.0 software program (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

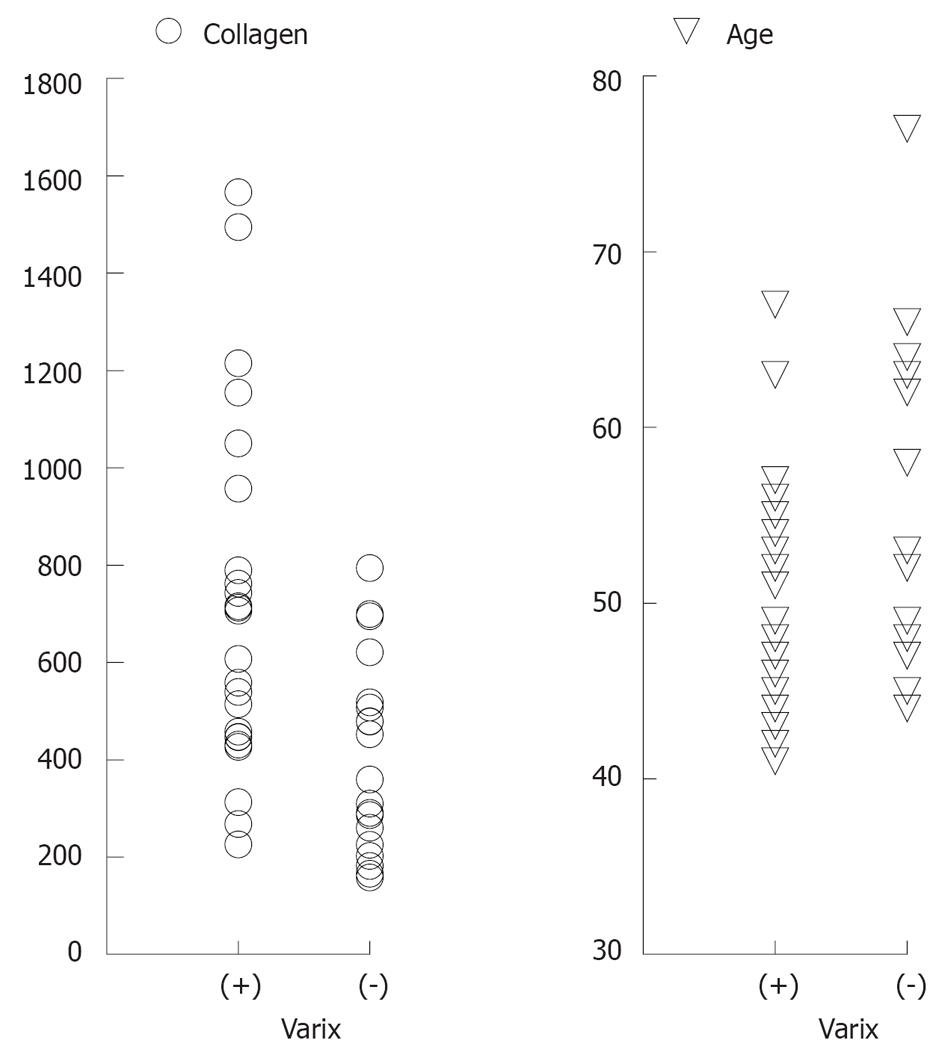

Twenty-five patients (56.8%) had esophageal varices, and 19 (43.2%) had no varice (Figure 1). A univariate analysis revealed a significant difference between patients with and without esophageal varices with regard to age and type IV collagen levels (Table 1 and Figure 2).

These two variables that were significantly linked to the presence of esophageal varices in the univariate analysis, and a factor previously reported[11], age, PT, and type IV collagen, were assessed by multivariate analysis. A logistic regression analysis identified type IV collagen as the only independent variable predictive for esophageal varices (P = 0.017) (Table 2). Whenever the type IV collagen level raised every 150 ng/mL, the odds ratio of esophageal varices doubled.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value |

| Collagen type IV | 2.02 | 1.13-3.60 | 0.017 |

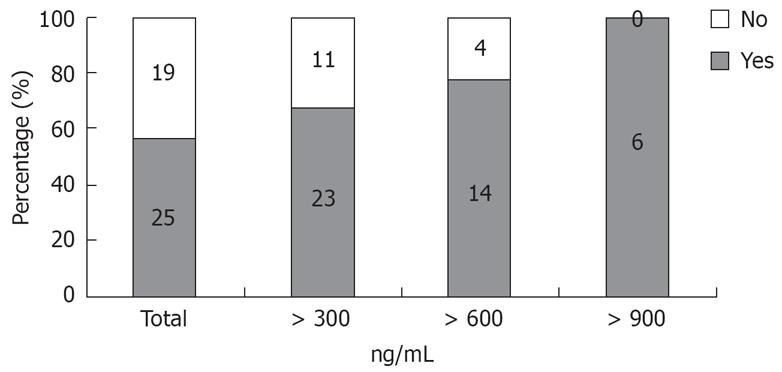

Figure 3 shows the positive predictive values at each cut off point of type IV collagen. The positive predictive value of esophageal varices with a type IV collagen value > 900 ng/mL (n = 6) was 100%.

Finally, the area under the curve (AUC) of type IV collagen as determined by ROC for predicting the presence of esophageal varices was 0.78 (Figure 4).

A rupture of esophageal varices is the most frequent complication of portal hypertension, occurring in one third of all cirrhotic patients, and is associated with a high mortality[1213]. The mortality rate from variceal bleeding is about 20% when patients are treated optimally in a hospital[14]. However, an appreciable proportion of patients with variceal bleeding die before reaching the hospital[15]. Numerous studies have shown that the prevention of UGI bleeding and early detection of esophageal varices reduces mortality, morbidity, and health care costs[16]. Nevertheless, Suzuki et al demanded further studies to determine which strategies are the most beneficial to patients and society in terms of preventing and treating esophageal varices, in a recent article[7]. We thus examined potential esophageal varice prediction factors for SAD on a medical checkup level.

In this study, a non-invasive marker for hepatic fibrosis (type IV collagen) had a high diagnostic accuracy for the detection of esophageal varices. The combination of abdominal ultrasound scan and this marker correctly identified, at a high rate, patients with esophageal varices. These examinations can be conducted on a medical checkup level, so we considered this approach to be of considerable diagnostic value.

A previous report showed the type IV collagen concentration was the most accurate in correctly identifying patients with severe histologic alcoholic hepatitis. At a cut-off of 150 ng/mL, type IV collagen was 89% sensitive and 77% specific[17]. First, patient sorting was conducted via the abdominal ultrasound test in this study. The alcoholic patients with splenomegaly and/or withering of the right liver lobe participated in this study. In these 44 patients, the value of type IV collagen was > 150 ng/mL in all specimens. As a result, when suspecting SAD, we thought it very meaningful to add the abdominal ultrasound test to the characteristics under evaluation.

In a previous report, Geoffroy and colleagues demonstrated that the independent factors of prothrombin index, alkaline phosphatase activity, and hyaluronate level predicted the presence of esophageal varices[11]. Nevertheless, their proposed model included two age-dependent serum markers, hyaluronate and alkaline phosphatase, both of which rise in serum with aging[18]. We therefore added only the prothrombin index as an examination item. Moreover, another report demonstrated a rise in amino-terminal procollagen III peptide (PIIINP) following alcohol withdrawal that is likely to be caused by intact PIIINP[19]. We thus decided not to include this fibrosis marker as an examination item at the time of hospitalization. Finally, we elected to add GTP and collagen type IV as examination items.

The serum concentration of laminin and type IV collagen have been reported to be increased in patients with alcoholic hepatitis and to correlate with the degree of inflammation[20–26]. In our study, logistic regression identified type IV collagen as the only independent variable predictive for esophageal varices. While based on the findings of these studies, laminin may be predictive for esophageal varices. However, the use of such testing is not covered by the national health insurance program in Japan, so we decided to exclude laminin from this study. We therefore hope that further study of esophageal varices in other countries will help to elucidate and confirm the predictive potential of laminin.

Antler et al found that in younger patients, the most common bleeding sites are those associated with alcoholism (esophageal varices, Mallory-Weiss tears, and hemorrhagic gastritis), accounting for 40%-60% of lesions in patients less than 55 years-of-age[27]. Another report demonstrated that younger patients had a trend toward more variceal bleeds (P = 0.39)[28]. In our research, there was a positive correlation of esophageal varices with younger age (P > 0.05). We think that younger alcoholic patients with high fibrosis markers should be evaluated by GI endoscopy.

In conclusion, this study suggests that the level of type IV collagen has a high diagnostic accuracy for the detection of esophageal varices in SAD. These results show that the non-invasive screening of patients who are at risk for variceal bleeding is possible, and that this approach may assist in the prevention of this most serious complication.

Bleeding from varices may occur in 15%-68% of patients with varices. Variceal hemorrhaging is associated with a high mortality rate, as well as high hospital costs.

The early detection of esophageal varices is critical for the effective prevention of variceal hemorrhaging. Adding an accurate non-invasive diagnostic model may improve the diagnostic accuracy in predicting esophageal varices without performing liver biopsy.

First, patient sorting for alcoholism was conducted via the abdominal ultrasound test in this study. The existence of esophageal varices with severe alcoholic disease was compared according to a number of clinical background variables. A univariate analysis revealed a significant difference in age and type IV collagen levels between the patients with and without esophageal varices. A logistic regression analysis identified type IV collagen as the only independent variable predictive for esophageal varices (P = 0.017). AUC of type IV collagen as determined by ROC for predicting expressed esophageal varices was 0.78.

The combination of an abdominal ultrasound scan and type IV collagen correctly identified, at a high rate, alcoholism patients with esophageal varices.

The type IV collagen and laminin are the major components of basement membranes. Early accumulation of type IV collagen and laminin, thus leading to the formation of basement membrane-like material in the space of Disse (capillarization), is considered a typical characteristic of alcoholic liver disease. The amount of collagen in the space of Disse has been shown to correlate significantly with the presence of alcoholic hepatitis and portal blood pressure.

This short paper summarized well the relevance of type IV collagen as a predictive factor for varices in alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

| 1. | Sutton R, Shields R. Alcohol and oesophageal varices. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30:581-589. |

| 2. | Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, Rinaldi V, De Santis A, Merkel C, Attili AF, Riggio O. Incidence and natural history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2003;38:266-272. |

| 3. | D'Amico G, Morabito A. Noninvasive markers of esophageal varices: another round, not the last. Hepatology. 2004;39:30-34. |

| 4. | Groszmann RJ, de Franchis R, In: Schiff ER, Sorrell MF, Maddrey WC; Portal hypertension. Schiff’s Disease of the Liver. Philadelphia, New York: Lippincott-Raven 1999; 387-442. |

| 5. | Sharara AI, Rockey DC. Gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:669-681. |

| 6. | Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Burroughs AK, Pagliaro L, Makuch RW, Bosch J, Stiegmann GV, Henderson JM, de Franchis R. Portal hypertension and variceal bleeding: an AASLD single topic symposium. Hepatology. 1998;28:868-880. |

| 7. | Suzuki A, Mendes F, Lindor K. Diagnostic model of esophageal varices in alcoholic liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:307-309. |

| 8. | Burroughs AK, McCormick PA. Natural history and prognosis of variceal bleeding. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;6:437-450. |

| 9. | Hosey RG, Mattacola CG, Kriss V, Armsey T, Quarles JD, Jagger J. Ultrasound assessment of spleen size in collegiate athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:251-254; discussion 251-254. |

| 10. | Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Tajiri T. New methods for the management of gastric varices. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5926-5931. |

| 11. | Vanbiervliet G, Barjoan-Marine E, Anty R, Piche T, Hastier P, Rakotoarisoa C, Benzaken S, Rampal P, Tran A. Serum fibrosis markers can detect large oesophageal varices with a high accuracy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:333-338. |

| 12. | Graham DY, Smith JL. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:800-809. |

| 13. | D'Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: a meta-analytic review. Hepatology. 1995;22:332-354. |

| 14. | D'Amico G, De Franchis R. Upper digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. Hepatology. 2003;38:599-612. |

| 15. | Nidegger D, Ragot S, Berthelemy P, Masliah C, Pilette C, Martin T, Bianchi A, Paupard T, Silvain C, Beauchant M. Cirrhosis and bleeding: the need for very early management. J Hepatol. 2003;39:509-514. |

| 16. | Jensen DM. Endoscopic screening for varices in cirrhosis: findings, implications, and outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1620-1630. |

| 17. | Castera L, Hartmann DJ, Chapel F, Guettier C, Mall F, Lons T, Richardet JP, Grimbert S, Morassi O, Beaugrand M. Serum laminin and type IV collagen are accurate markers of histologically severe alcoholic hepatitis in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;32:412-418. |

| 18. | Guechot J, Poupon RE, Poupon R. Serum hyaluronan as a marker of liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:103-106. |

| 19. | Campbell S, Timms PM, Maxwell PR, Doherty EM, Rahman MZ, Lean ME, Danesh BJ. Effect of alcohol withdrawal on liver transaminase levels and markers of liver fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1254-1259. |

| 20. | Annoni G, Colombo M, Cantaluppi MC, Khlat B, Lampertico P, Rojkind M. Serum type III procollagen peptide and laminin (Lam-P1) detect alcoholic hepatitis in chronic alcohol abusers. Hepatology. 1989;9:693-697. |

| 21. | Lotterer E, Gressner AM, Kropf J, Grobe E, von Knebel D, Bircher J. Higher levels of serum aminoterminal type III procollagen peptide, and laminin in alcoholic than in nonalcoholic cirrhosis of equal severity. J Hepatol. 1992;14:71-77. |

| 22. | Niemela O, Risteli L, Sotaniemi EA, Risteli J. Type IV collagen and laminin-related antigens in human serum in alcoholic liver disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 1985;15:132-137. |

| 23. | Niemela O, Risteli J, Blake JE, Risteli L, Compton KV, Orrego H. Markers of fibrogenesis and basement membrane formation in alcoholic liver disease. Relation to severity, presence of hepatitis, and alcohol intake. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1612-1619. |

| 24. | Niemela O, Risteli J, Blake JE, Risteli L, Compton KV, Orrego H. Connective tissue metabolism and alcohol intake in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 1991;1:351-355. |

| 25. | Nouchi T, Worner TM, Sato S, Lieber CS. Serum procollagen type III N-terminal peptides and laminin P1 peptide in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1987;11:287-291. |

| 26. | Robert P, Champigneulle B, Kreher I, Gueant JL, Foliguet B, Dollet JM, Bigard MA, Gaucher P. Evaluation of fibrosis in the disse space in noncirrhotic alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1989;13:176-180. |

| 27. | Antler AS, Pitchumoni CS, Thomas E, Orangio G, Scanlan BC. Gastrointestinal bleeding in the elderly. Morbidity, mortality and cause. Am J Surg. 1981;142:271-273. |

| 28. | Segal WN, Cello JP. Hemorrhage in the upper gastrointestinal tract in the older patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:42-46. |