Published online Mar 21, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1797

Revised: December 7, 2007

Published online: March 21, 2008

Fibro-muscular dysplasia (FMD) is a rare but well documented disease with multiple arterial aneurysms. The patients, usually women, present with various clinical manifestations according to the specific arteries that are affected. Typical findings are aneurysmatic dilatations of medium-sized arteries. The renal and the internal carotid arteries are most frequently affected, but other anatomical sites might be affected too. The typical angiographic picture is that of a "string of beads". Common histological features are additionally described. Here we present a case of a 47-year-old woman, who was hospitalized due to intractable abdominal pain. A routine work-up revealed a liver mass near the portal vein. Before a definite diagnosis was reached, the patient developed massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding. In order to control the hemorrhage, celiac angiography was performed revealing features of FMD in several arteries, including large aneurysms of the hepatic artery. Active bleeding from one of these aneurysms into the biliary tree indicated selective embolization of the hepatic artery. The immediate results were satisfactory, and the 5 years follow-up revealed absence of any clinical symptoms.

- Citation: Shussman N, Edden Y, Mintz Y, Verstandig A, Rivkind AI. Hemobilia due to hepatic artery aneurysm as the presenting sign of fibro-muscular dysplasia. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(11): 1797-1799

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i11/1797.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.1797

A 47-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency department (ED) with epigastric abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for 2 d. The patient denied fever or changes of bowel habits. The pain did not subside following a medication with antacids and H2 blockers prior to admission.

Physical examination revealed a soft abdomen with epigastric tenderness and the absence of jaundice and peritoneal irritation signs. It revealed no further findings.

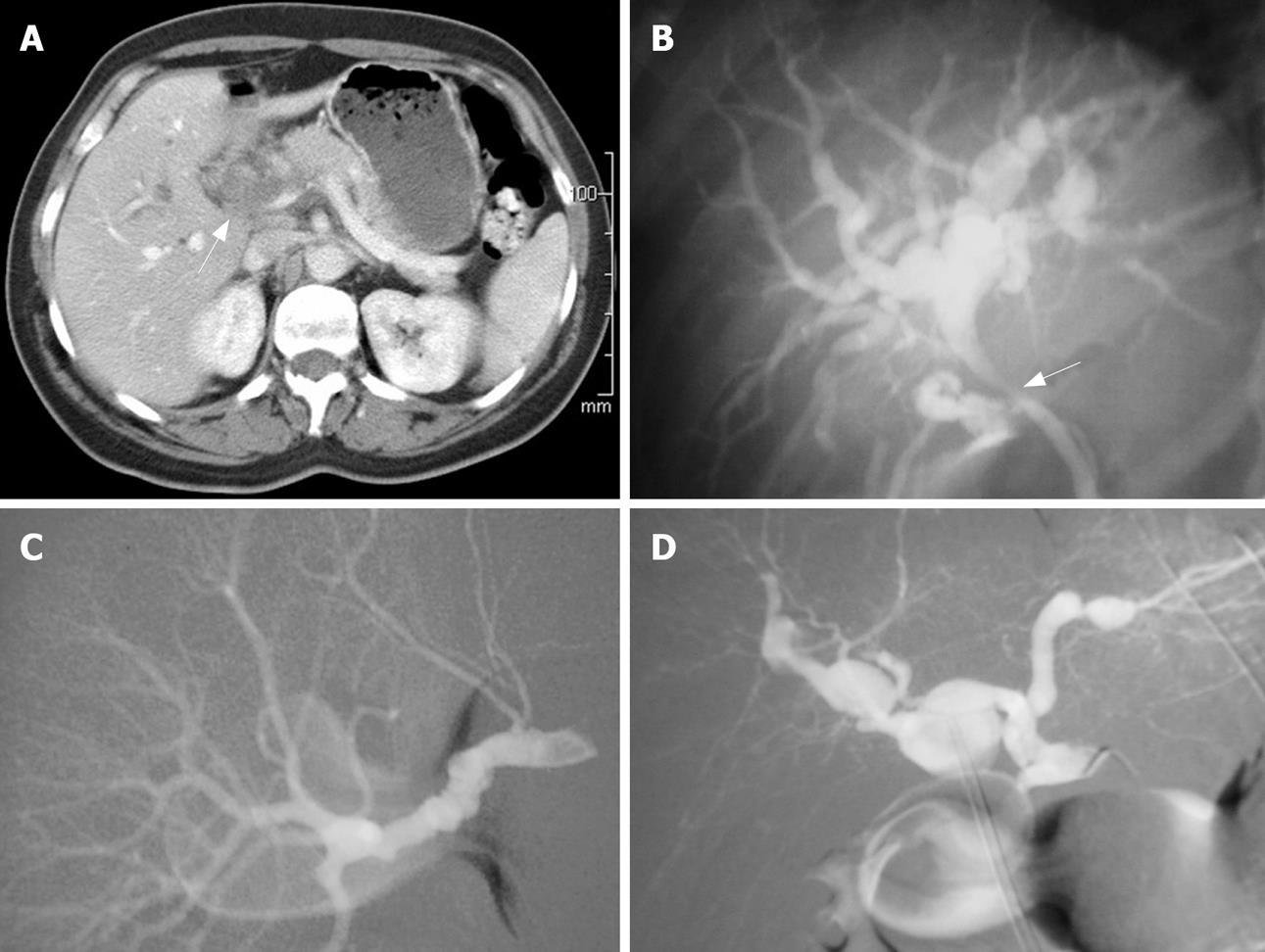

Upon admission, white blood count, liver function test, bilirubin levels, and amylase activity were within the normal range. Abdominal X-ray was within normal limits. Abdominal ultrasound (US) demonstrated a cystic structure near the hepatic hilum. Gastro-duodenoscopy was performed without revealing any pathology. An abdominal CT scan demonstrated a soft tissue mass encapsulating the portal vein and hepatic artery causing intra-hepatic biliary tree dilatation (Figure 1A). Following an increase of the total bilirubin level of up to 0.39 g/L, endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreaticography (ERCP) was performed. ERCP revealed a common hepatic duct stricture with proximal biliary dilatation (Figure 1B). A stent was inserted without complications. Biliary brush biopsy was taken and turned out to be normal. With the working diagnosis of a neoplastic process, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guided biopsy was scheduled. While awaiting the procedure, the patient's condition stabilized, the pain resolved, and she was discharged. A few days later she presented with complaints of severe abdominal pain accompanied by jaundice and hematemesis. Upon arrival to the ED her pulse was non-palpable and systolic blood pressure was 70 mmHg. After aggressive fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion emergent gastro-duodenoscopy was performed, once again without any pathologic finding. Abdominal US revealed the described soft tissue mass which had doubled in size and appeared to be pulsating. With the working diagnosis that the tissue mass was of vascular origin, angiography was carried out. The hepatic, renal, and iliac arteries had a radiographic appearance of a “string of beads” (Figure 1C and D), which characterizes fibro-muscular dysplasia (FMD). In order to prevent further bleeding from hepatic artery aneurysms to the biliary system, embolization of the proper hepatic artery using a thrombogenic coil was performed. Elevated levels of bilirubin indicated concurrent ERCP which revealed a clogged stent, obstructed by blood clots, and which thus was replaced. After the procedure the patient did not suffer from gastrointestinal bleeding, and elevated liver enzyme levels gradually resolved. The patient was discharged 52 d after her first admission.

Today, 5 years after the first symptoms, the patient has no clinical signs or symptoms related to hepatic artery embolization, and no laboratory or radiographic changes are evident.

FMD is a disorder which leads to arterial stenosis and most commonly affects the renal and internal carotid arteries in 60%-75% and 25%-30% of cases, respectively[12]. It is double as common among females and most cases are diagnosed in patients younger than 50 years.

The pathogenesis is not well understood and might include a genetic predisposition, hormonal influences, mechanical factors, or ischemia. All of the above mentioned parameters might contribute to deposition of fibrous lesions, which are classified into five categories according to the affected arterial layer and the histological pattern[3].

Clinical manifestations result from ischemia (due to arterial stenosis), hemorrhage (due to ruptured aneurysms), and embolization of intravascular thrombi formed within the aneurysms. Thus, they may vary widely depending on the arteries involved[4].

A common manifestation of FMD is reno-vascular hypertension due to renal artery stenosis. The clinical presentation of an affected carotid artery may vary from headache and lightheadedness to cerebrovascular accident.

The gold standard imaging technique for the diagnosis of FMD is angiography, which demonstrates several features such as beading of the vessel and concentric stenosis. The classical appearance in the most common of the five pathological subtypes is a “string of beads”[2]. Other diagnostic modalities include duplex-ultrasound, CT-angiography, and MR-angiography[5].

Treatment of FMD depends upon the arteries involved and the clinical presentation. In cases of regional ischemia, revascularization (by either endovascular or surgical approach) is the preferred treatment. Hemorrhagic complications are treated by ligation or embolization of the affected artery. Hemobilia is a rare clinical condition which may be fatal if not treated promptly. It was first described in 1948 following abdominal trauma[6]. Since then, many patients suffering from hemobilia were described, most of them were treated surgically[7]. Endovascular embolization of ruptured hepatic artery aneurysms have been described[89] but not in the context of FMD.

FMD of the hepatic artery is only one of many etiologies that might cause hemobilia and it mandates treatment even if asymptomatic[10]. Only one case in which FMD was the underlying cause for hemobilia was described in the English literature[11]. That patient was treated surgically by ligation of the common hepatic and gastroduodenal arteries. The patient we report was the first who was treated with a minimally invasive endovascular technique for FMD related hemobilia.

In some cases of controllable gastrointestinal bleeding due to FMD related hemobilia, if the patient’s hemodynamic status permits, selective angiography and embolization of ruptured hepatic artery aneurysms may be highly effective. The endovascular approach holds less morbidity and mortality than surgery and serves both as a diagnostic and a therapeutic tool. Success in treating such a patient is dependent upon good communication and cooperation between the surgeon and the interventional radiologist.

| 1. | Luscher TF, Keller HM, Imhof HG, Greminger P, Kuhlmann U, Largiader F, Schneider E, Schneider J, Vetter W. Fibromuscular hyperplasia: extension of the disease and therapeutic outcome. Results of the University Hospital Zurich Cooperative Study on Fibromuscular Hyperplasia. Nephron. 1986;44 Suppl 1:109-114. |

| 2. | Mettinger KL. Fibromuscular dysplasia and the brain. II. Current concept of the disease. Stroke. 1982;13:53-58. |

| 3. | Stanley JC, Gewertz BL, Bove EL, Sottiurai V, Fry WJ. Arterial fibrodysplasia. Histopathologic character and current etiologic concepts. Arch Surg. 1975;110:561-566. |

| 4. | Lüscher TF, Lie JT, Stanson AW, Houser OW, Hollier LH, Sheps SG. Arterial fibromuscular dysplasia. Mayo Clin Proc. 62:931-952. |

| 5. | Carman TL, Olin JW, Czum J. Noninvasive imaging of the renal arteries. Urol Clin North Am. 2001;28:815-826. |

| 6. | Sandblom P. Hemorrhage into the biliary tract following trauma - “traumatic hemobilia”. Surgery. 1948;24:571-586. |

| 7. | Harlaftis NN, Akin JT. Hemobilia from ruptured hepatic artery aneurysm. Report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Surg. 1977;133:229-232. |

| 8. | Nakashima M, Suzuki K, Okada M, Takada K, Kobayashi H, Hama Y. Successful coil embolization of a ruptured hepatic aneurysm in a patient with polyarteritis nodosa accompanied by angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1362-1364. |

| 9. | Srivastava DN, Sharma S, Pal S, Thulkar S, Seith A, Bandhu S, Pande GK, Sahni P. Transcatheter arterial embolization in the management of hemobilia. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:439-448. |

| 10. | Berceli SA. Hepatic and splenic artery aneurysms. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18:196-201. |

| 11. | Unuvar E, Piskin B. Hemobilia from a ruptured hepatic artery aneurysm in a 16-year-old girl. Turk J Pediatr. 1989;31:63-70. |