CASE REPORT

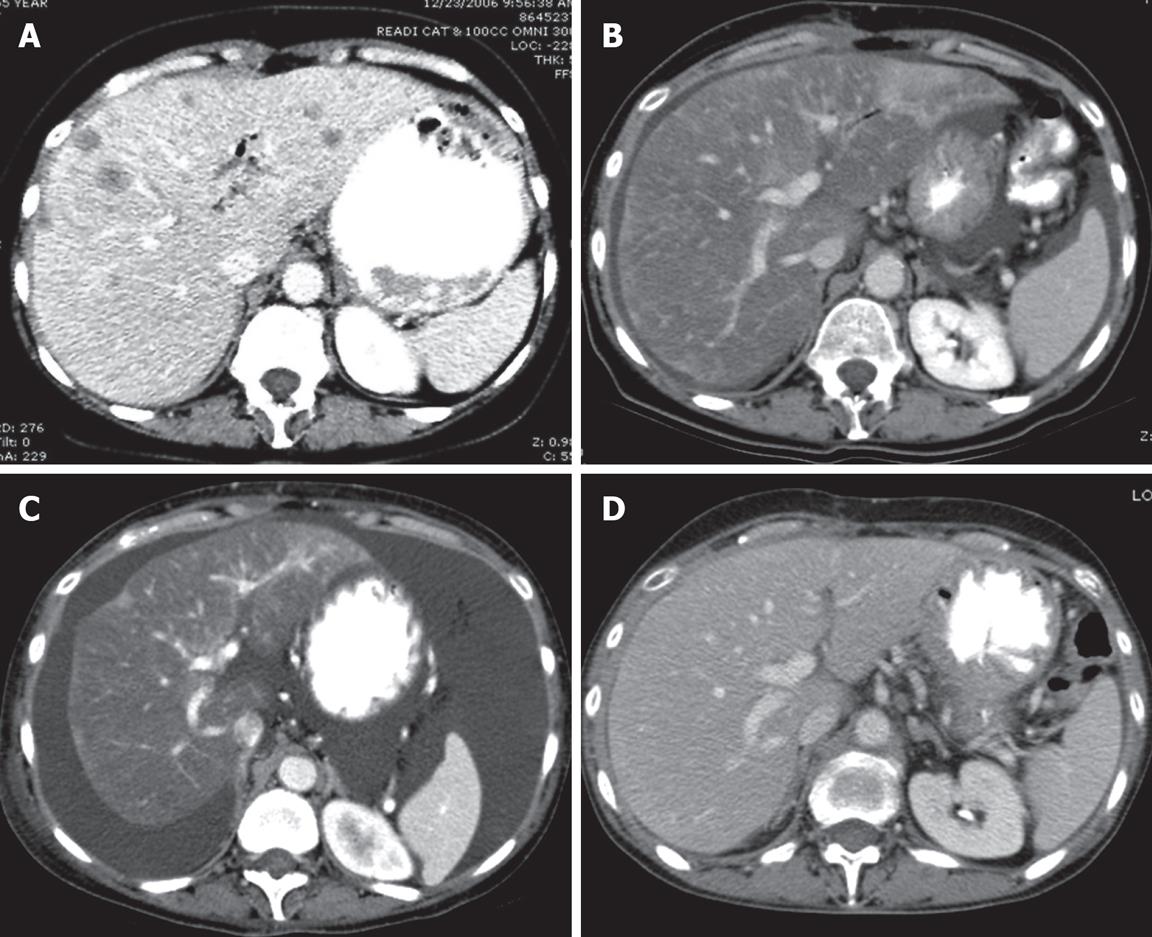

A 55-year-old woman presented to our institution in November 2006 with newly diagnosed, untreated metastatic pancreatic cancer, as well as biopsy-proven liver metastases and peritoneal deposits. She was asymptomatic with an ECOG performance status of 0, had no risk factors for hepatitis or cirrhosis, and her physical examination was unremarkable. Her hemoglobin was 102 (120-160 g/L), albumin was 33 (35-50 g/L), alkaline phosphatase was 300 (30-130 U/L), and total bilirubin was 1.54 g/L (less than 1.20 g/L). CA19-9 and CEA were elevated at presentation to 464 (0-37.0 U/mL) and 12.5 (0-3.0 ng/mL), respectively. A CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis in December 2006 revealed multiple bilateral lung nodules which measured 5 mm or less, a 4.7 cm × 3.2 cm neoplasm at the head of the pancreas, and innumerable liver metastases (Figure 1A).

Figure 1 Computed tomography (CT) of the liver.

CT scan is the initial imaging study. A: CT of the liver after contrast enhancement showing numerous liver metastases; B: CT scan 4 mo after initial study showing marked diminution of the metastases and marked fatty infiltration of the liver; C: The liver 2 mo after B showing no evidence of metastasis but findings which simulate cirrhosis with ascites, and irregular contours with retraction. This constellation of CT findings is consistent with a diagnosis of peudocirrhosis; D: CT scan 2 mo after C showing a nearly normal liver and only a trace of ascites present in the pelvis (image not shown).

The patient began systemic chemotherapy with gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) and oxaliplatin (100 mg/m2) every other week in December 2006. On a restaging CAT scan obtained after 3 cycles of treatment, innumerable hepatic metastases appeared less conspicuous. After 8 cycles of the therapy, she remained clinically well, CEA and CA19 were declined by > 50%, and CT scan on 4/10/2007 revealed nearly complete resolution of pulmonary nodules and hepatic metastases while the pancreatic mass remained stable. Fatty infiltration of the liver and new ascites were noted (Figure 1B).

In May 2007, she developed increasing bilateral ankle edema and ascites, associated with dyspnea, progressive weight gain, and declining performance status. Gemcitabine and oxliplatin were discontinued. The ascites and fluid retention continued to worsen despite escalation of diuretics, and serum albumin decreased to 24 g/L, cardiac echocardiogram and duplex Doppler ultrasound of the lower extremities revealed no evidence of congestive heart disease or venous thrombosis. CT scan on June 7, 2007 revealed worsening ascites with a stable pancreatic mass. However, it also revealed a lobular hepatic contour, segmental atrophy, and capsular retraction mimicking the appearance of cirrhosis (Figure 1C). Hepatic Doppler ultrasound on June 21, 2007 revealed patent splenic, portal confluence, and hepatic veins with normal direction of flow. Her albumin declined to a nadir of 17 g/L. Bilirubin and ALT (SGPT) were normal, and AST (SGOT) was < 2X upper limit of normal. The patient underwent a large volume paracentesis and the serum-to-ascites albumin gradient was greater than 11 g/L, indicating portal hypertension as the cause of her ascites. She was managed with aggressive diuresis and weekly albumin infusions. Over the next three months, she had marked improvement in her overall status with resolution of peripheral edema, diminished ascites, and normalization of albumin to 37 g/L. The patient’s follow-up CT scan 14 wk after discontinuation of chemotherapy revealed a near resolution of pseudocirrhotic appearance of the liver and ascites along with a decrease in the size of the pancreatic head mass (Figure 1D). CA19-9 was decreased further to 64.

DISCUSSION

In patients with metastatic cancer involving the liver, treatment with chemotherapy can result in areas of retracted tumor tissue and scarring. This entity is referred to as pseudocirrhosis because it resembles macronodular cirrhosis radiographically and can be associated with hepatic decompensation, while lacking of the classic pathologic attributes of cirrhosis[1]. Pseudocirrhosis has been reported almost exclusively in patients undergoing treatment for metastatic breast cancer. We report herein the first case of pseudocirrhosis arising in a patient with metastatic pancreatic cancer.

A wide range of chemotherapeutic agents are associated with pseudocirrhosis in patients with breast cancer, including adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, cisplatin, carmustine, tamoxifen, paclitaxel, megestrol acetate, vinblastine, etoposide, thiotepa, ifosfamide, navelbine, and vincristine[1–3]. Patients exhibit radiographic findings of cirrhosis, such as capsular retraction with volume loss and lobulation of the liver contour adjacent to the treated metastatic disease[13–5]. The degree of change tends to correlate with the extent of metastatic burden in the liver[4]. In the series by Young et al, 52% and 27% of cases resulted in ascites and splenomegaly, respectively[1]. While it is rare, there are case reports on severe manifestations of portal hypertension, such as hepatic encephalopathy or variceal bleeding, associated with pseudocirrhosis, suggesting that the life threatening clinical consequences can be equivalent to those seen in classic cirrhosis despite the differences in respective pathophysiology[136].

The mechanism of pseudocirrhosis arising in the setting of chemotherapy-induced regression of liver metastases is unclear. It has been proposed that tumor shrinkage and subsequent scar formation around the treated liver lesions are a possible mechanism, since volume loss and capsular retraction typically occur adjacent to the treated metastases. Alternatively, nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) in response to chemotherapy-induced hepatic injury has been proposed as the causal mechanism of pseudocirrhosis[178]. The formation of regenerative hepatic nodules with subsequent compression and atrophy of intervening parenchyma without hepatic fibrosis is the hallmark of NRH[1]. NRH has been associated with various chemotherapeutic agents including oxaliplatin, 5-FU, and agents used in acute leukemia[79–11]. Oxaliplatin has been linked to the development of hepatic sinusoidal lesions, with areas of hepatic regeneration which can occasionally reach a pattern of NRH. However, clinically significant hepatic decompensation in association with these histopathologic findings has not been reported with oxaliplatin. Gemcitabine-associated liver toxicities have been very rarely reported[12–15].

To our knowledge, this represents the first reported case of pseudocirrhosis arising in the setting of regression of liver metastases from pancreatic cancer. The absence of a liver biopsy is the major limitation in fully understanding the etiology of this patient’s pseudocirrhosis. Since this patient had dramatic resolution of liver metastases and declining tumor markers prior to developing pseudocirrhosis, we cannot distinguish between tumor regression with scar formation or hepatotoxic effects of chemotherapy as potential mechanisms. However, the complete resolution of the radiographic and clinical hallmarks of pseudocirrhosis with cessation of chemotherapy suggests that, in this case, pseudocirrhosis was due, in part, to chemotherapy-associated hepatic injury

In conclusion, this case illustrates that pseudocirrhosis can occur in pancreatic cancer as well as in breast cancer. Clinicians should be aware of this entity when treating patients with extensive liver metastases from pancreatic cancer. Early recognition and appropriate management, including discontinuation of implicated chemotherapeutic agents, cannot only prevent further liver damage and life-threatening consequences of portal hypertension, but can also lead to a full recovery of liver function.