INTRODUCTION

Myelin sheath tumors comprise schwannoma, neu-rofibroma, neurofibromatosis and neurogenic sarcoma. More than 90% are benign[1] and present in young to middle-aged subjects (twice in women than in men). They are usually asymptomatic and hence discovered incidentally[2]. Schwannoma is more common than neurofibroma. Its origin is often single. The 10% with a multiple origin[3] are classified as neurofibromatosis II, a disorder of autosomal dominant inheritance[4]. When located in gastrointestinal tract, schwannoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma and leiomyoblastoma constitute the gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST)[5]. Peripheral nerve sheath tumors account for 2%-6% of the GIST, but there are few reports of neurogenic tumors in the biliary system. The retroperitoneum is rarely involved[6]. Schwannomas arise only occasionally in the extrahepatic ducts and provoke symptoms by compressing adjacent structures[7]. Their symptoms were so varied to make their preoperative diagnosis very difficult. A cholestatic syndrome in a healthy woman is described in this report.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 41-year-old woman who presented with ingravescent pruritus lasting one month, a 4 kg weight loss and scleral subicterus. Her clinical and family history were devoid of significance. There was no history of drug intake. The physical examination evidenced a normal spleen and the absence of lymphadenopathies in the explorable sites. There was evidence of diffuse scratching lesions on the lower limbs and subicteric sclerae.

Laboratory results: RBC 4.49 × 106/L (4.2-5.4), WBC 4.76 × 103/L (4-10), hemoglobin 14.4 g/dL (12-16), ESR 21 mm/s, PCR 0.76 mg/L (< 3), LDH 412 U/L (313-618), total proteins 8.7 g/dL (6.3-8.2), total bilirubin 2.1 mg/dL (0.2-1.3), conjugated bilirubin 1.4 mg/dL (0-0.4), bile acids 6.8 μmol/L (0-6), AST 90 U/L (< 40), ALT 161 U/L (9-56), GGT 290 U/L (12-58), ALPh 192 U/L (38-126), amylase 60 U/L (30-110), antimitocondrial antibody negative, CEA 1.3 ng/mL (< 5), CA 19-9 48.5 U/mL (< 37), CA-125 39.6 U/mL (< 35).

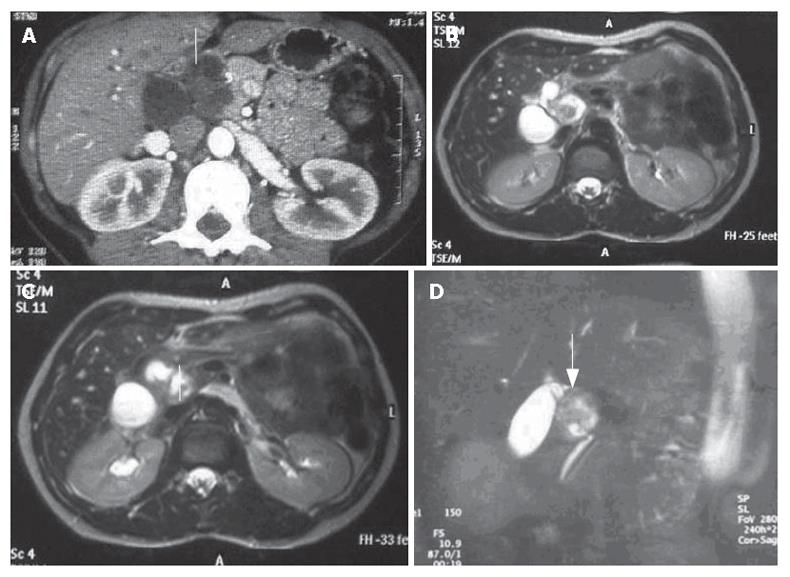

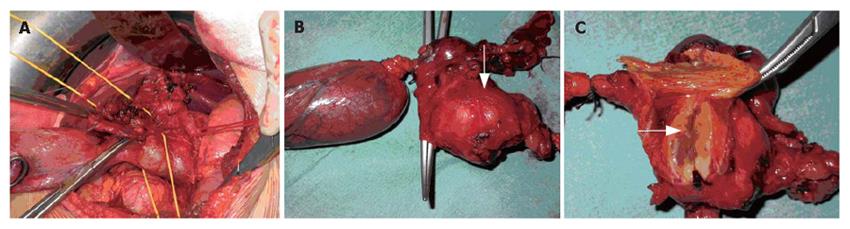

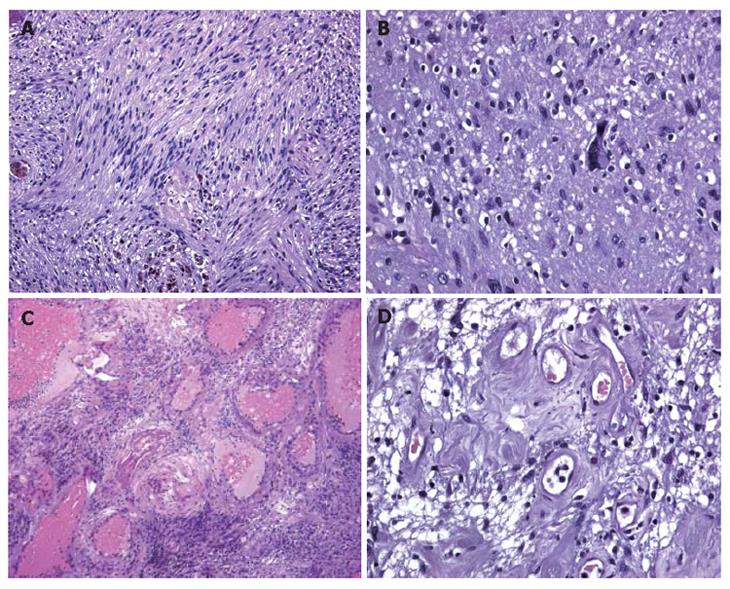

A CT scan (Figure 1A) revealed a lesion between the head of the pancreas and the gall bladder infundibulum near to the middle segment of the common bile duct. The mass was heterogeneous with a diameter of 3 cm. The upstream bile ducts were slightly dilated. The gall bladder was overdistended and contained a 2 cm stone in the fundus. Cholangio-MRI with the secretin test (Figure 1B-D) dislcosed a hypointensive signal in the weighted T1 sequences. The mass was assigned to the pancreatic isthmus. Its size and lack of uniformity were confirmed and a neoplastic origin was suspected. A good response to secretin showed that the function of the pancreas was unimpaired. Biliopancreatic echoendoscopy ruled out involvement of the pancreas, confirmed distention of the gall bladder and disclosed a solid, non-vascularised formation with many anaechogenic areas. Its contiguity with the portal axis rendered percutaneous biopsy inadvisable and exploratory laparotomy was performed. The formation involved the intermediate tract of the common bile duct between its confluence with the cystic duct and the prepancreatic tract (Figure 2A). The middle segment of the common bile duct was resected, together with the gall bladder (overdistended, but uninflamed) and the lymph nodes. A bilio-digestive Roux-en-Y anastomosis was performed on the loop. Gross inspection showed an intramural lesion under the mucosa with a diameter of 4 cm (Figure 2B and C). Histological examination revealed the proliferation of interwoven bundles of fused cells, occasionally separated by slacker, oedematous areas with a pseudocystic appearance (Figure 3A). There were also a few cells with an hyperchromic, atypical and bizarre nucleus (Figure 3B), ectatic, congested and partially thrombosed vessels (Figure 3C), and signs of perivascular hyalinisation (Figure 3D).

Figure 1 A: CT scan showing a very heterogeneous formation with a liquid content in close contiguity to the CBD (white arrow); B, C, D: Cholangio-MRI reveals a solid formation with a hypointensive signal in the weighted T1 sequences at the pancreatic isthmus (white arrows) with dilation of the upstream bile ducts.

Figure 2 Intraoperative view of involvement of the intermediate tract of the common bile duct between its confluence with the cystic duct (A) and the prepancreatic tract (B) and (C) Gross inspection showing that the lesion (arrows) is solid and situated intramurally and below the mucosa in close contiguity with the CBD.

Figure 3 A: Histological examination showing that inter-woven bundles of fused cells separated by slacker, oedematous areas with a pseudocystic appearance (Antoni A schwannoma growth pattern); B: Histological examination showing a few cells with hyperchromic, atypical and bizarre nuclei.

Histological examination showing a few cells with hyperchromic, atypical and bizarre nuclei; C: Histological examination showing hyalinisation and ectatic and partially thrombosed vessels; D: Histological examination showing perivascular hyalinisation.

Immunohistochemical investigation showed that the tumor cells were vimentin and protein S-100 positive, and alpha-actin, desmin, CD34, cytokeratin pan (clone ARE1/E3) and CD117 negative. The postoperative course was uneventful. The cholestatic and hepatic cytolytic indices normalised after two months, with definite disappearance of pruritus, which continue to be normal after one year .

DISCUSSION

Schwannoma of the bile ducts is particularly rare, and it usually arises in the head, neck, spinal cord and the extremities[8], but rarely in retroperitoneum (6% of primary retroperitoneal tumors)[9]. It is usually located in the para-vertebral regions or in the pre-sacral pelvic zone[2,10]. The bladder and abdominal wall are occasionally involved. Liver, rectal colon and esophageal involvement has been described[11-14], whereas only nine cases of schwannoma of the extrahepatic biliary tract and one case of benign schwannoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament have been reported since the 1970s[7,15-23]. Determination of tumor location must be done with great care when mass exists between the liver and the retroperitoneum, especially when the mass is hypovascular. Pre-surgical diagnosis of the tumor is very difficult because early clinical detection is limited until it gives a palpable mass or compresses the surrounding organs[6].

Diagnosis is usually entrusted to CT and MRI. The gastrointestinal schwannomas appeared as a round or oval homogeneously attenuating, well-defined mass with frequent signs of degeneration, such as cysts and calcifications on CT[24]. Recently it was reported that CTs do not reveal tumor capsule, cystic change, necrosis or calcification in any of the observed schwannomas[25]. Weighted T1 images disclose masses with low-medium signal intensity, whereas this is high in the weighted T2 images owing to alternation of the Antoni A and B areas and secondary degeneration[26].

In the present case, CT illustrated a hypodense and very heterogeneous formation initially referable to duodenal diverticulum. The MRI images were marked by slight weighted T2 hyperintensity due to the partially fluid content. A good response to secretin showed that the function of the pancreas was unimpaired.

We did not employ PET with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake since it has been widely used to quantify the metabolism of malignant bone and soft-tissue malignant tumors, whereas little is known about FDG uptake in benign lesions. FDG PET is of limited value for the preoperative differentiation of schwannoma versus sarcoma[27]. Thus, a high FDG uptake is rather common in schwannoma[28].

The macroscopic growth pattern of the tumor mass was atypical. The two schwannoma growth patterns are called Antoni A and Antoni B. Elongated cells form an irregular, but compact palisade and the tissue arrangement is loose and there are cystic spaces between the cells[29]. In some cases, insufficient vascularisation of the mass may lead to degeneration in the form of cysts, calcifications, haemorrhages and hyalinisation[30]. These degenerative tumors are called “ancient schwannomas”. Morphologic and immunophenotypic features of the lesion pointed to a so-called “ancient schwannoma”, with reactive lymph nodes as described in the literature[31]. Digestive tract schwannomas are different from their soft tissue counterpart; they are not encapsulated and have an intramural growth pattern. Moreover, they are different both histologically and immunohistochimically from peripheral schwannomas. Gastrointestinal schwannomas, as in our case, are usually negative for CD34, CD117 and muscle cell markers, whereas they are strongly positive for vimentin and S100 protein. This typical combination differentiates schwannomas of the digestive tract from GIST. This differentiation is of practical importance. Gastrointestinal schwannomas are benign and associated with a good prognosis since post-surgical recurrences are unusual[32], even when treated only with enucleation. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, on the other hand, present a negative course in more than 50% of the cases[33,34].

The distinctive feature of this case is the complexity of its diagnosis. Conventional radiography was unable to provide a precise picture of the nature and location of the mass. A diagnosis deduced from the instrumental finding often awaits intraoperative and definitive histological confirmation[6]. Despite its complications, resection remains the treatment of choice. In the present case, only explorative laparotomy was able to demonstrate the seat and the nature of the lesion.

Lastly, in our case the postoperative course was uneventful and the cholestatic symptoms regressed two months after the operation.