Published online Feb 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i7.1141

Revised: December 3, 2006

Accepted: January 15, 2007

Published online: February 21, 2007

Lipoma within an inverted Meckel’s diverticulum presenting with hemorrhage and partial intestinal obstruction is an exceptional clinical entity. We report a case of 47-year-old male with a history of recurrent episodes of partial intestinal obstruction and melena due to a subserosal lipoma located in the base of an inverted Meckel’s diverticulum. According to our knowledge, this is the first case of a lipoma within a Meckel’s diverticulum giving rise to this clinical scenario without the existence of heterotrophic gastric or pancreatic tissues.

- Citation: Karadeniz Cakmak G, Emre AU, Tascilar O, Bektaş S, Uçan BH, Irkorucu O, Karakaya K, Ustundag Y, Comert M. Lipoma within inverted Meckel’s diverticulum as a cause of recurrent partial intestinal obstruction and hemorrhage: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(7): 1141-1143

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i7/1141.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i7.1141

Tumor of Meckel’s diverticulum occurs infrequently. Moreover, the association of a lipoma within the inverted Meckel’s diverticulum as a leading point of bleeding and recurrent episodes of partial intestinal obstruction is such an unusual circumstance that might be considered quite impossible.

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most prevalent congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract, which is reported to occur in 1%-3% of the general population and autopsy series[1,2]. However, the lifetime risk of complication development in patients with Meckel’s diverticulum was proposed to be less than 5% in recent investigations[3]. These complications included intestinal obstruction, intussusceptions, inflammation and bleeding.

Lipomas are the rare benign tumors of the small intestine with no malignant potential and mostly encountered incidentally during investigation of the gastrointestinal tract for another reason, since they are usually asymptomatic[4]. As small intestinal lipoma is relatively infrequent, it is even a rarer source of gastrointestinal bleeding.

We present a case of a 47-year-old man with fatigue, chronic abdominal pain and tarry stool due to an inverted Meckel's diverticulum with a subserosal lipoma. This is a special case that has not appeared in literature over the past 4 decades. Although the incidence of Meckel’s diverticulum is high, inversion is a scarsely diagnosed entity and the association of a lipoma within the inverted Meckel’s diverticulum as a leading point of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage without the existence of heterotopic gastric and pancreatic tissues and recurrent partial intestinal obstruction is an exceptional case.

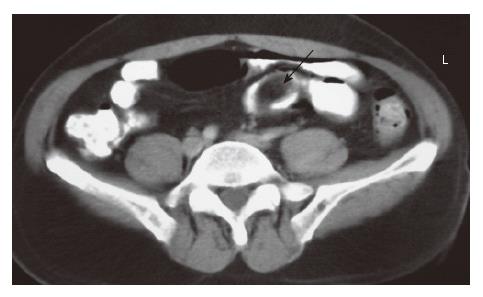

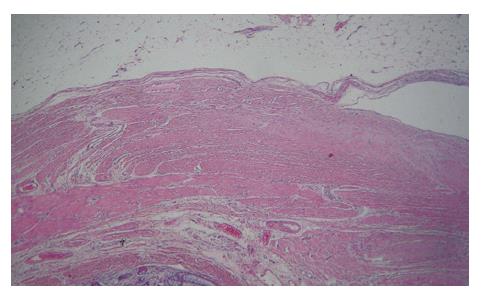

A 47-year-old man was admitted to our clinic with fatigue, recurrent episodes of constipation and abdominal pain. Melena was mentioned on admission. He denied vomiting, fever, or chills. He had had symptoms intermittently for about 4 mo, leading to several hospital visits. Over the previous 2 mo, the episodes of pain became more pronounced with radiation to his back. The patient was not using any specific medication and his medical history did not suggest a major disease. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 37°C, a pulse rate of 90 beats per minute (bpm), a blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg, and a respiration rate of 18 breaths per minute. The patient was pale-looking without abdominal tenderness, guarding or rebound and norm active bowel sounds were auscultated. Examination of heart and lungs revealed no abnormal findings. Rectal examination revealed tarry fecal content. Clear gastric content was obtained on nasogastric aspiration. The initial laboratory workup was as follows: hematocrit, 33%; hemoglobin, 11.2 g/dL; white blood cells, 10 500/mm3 with a normal differential count; platelets, 195 000/mm3; blood glucose, 87 mg/dL; blood urea, 25 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.8 mg/dL; SGOT, 32 IU/L; SGPT,25 IU/L; LDH, 54 IU/L; total bilirubin, 0.4 mg/dL; direct bilirubin, 0.2 mg/dL; and Na+, 138 meq/L; andK+, 3.7meq/L. Fecal occult blood test was positive. A gastrointestinal cause was sought in order to explain the patient’s hemorrhage. He had received upper and lower gastrointestinal tract endoscopic examinations without identification of a specific bleeding etiology except a little amount of blood residue in terminal ileum. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed mildly dilated loops of proximal small bowel and a polypoid, 4 cm × 2 cm mass lesion with fatty density localized in the left lower quadrant and a suspicious filling defect in cecum (Figure 1). A pedinculated lipoma was assumed to be the underlying cause of recurrent partial intestinal obstruction and bleeding. He was taken to the operating room with the diagnosis of symptomatic small bowel lipoma. At surgery, an inverted Meckel’s diverticulum induced by a pedinculated subserosal lipomatous solid mass nearly obstructing the lumen with ulcer and hemorrhage was found 40 cm from the ileocecal valve (Figure 2). Segmental resection of the ileal loop harboring the lesion was carried out and an end-to-end ileo-ileal anastomosis was performed. The lipoma within the inverted Meckel’s diverticulum as a leading point of obstruction and bleeding was 5 cm long and 3 cm in diameter. Pathologic evaluation of the specimen confirmed the diagnosis of a subserosal lipoma within the inverted Meckel’s diverticulum and revealed neither heterotrophic gastric and pancreatic tissue nor signs of malignancy (Figure 3). Five days after intervention, the patient was discharged from the hospital without any complication.

The omphalomesenteric duct connects the mid gut and yolk sac in seven weeks of gestation and during the eighth week, it normally undergoes obliteration[5]. Under circumstances of failure or incomplete vitelline duct obliteration, a spectrum of abnormalities appears, the most common of which is Meckel’s diverticulum. Omphalomesenteric fistula, enterocysts or a fibrous band connecting the small intestine to the umbilicus are the other pathologies that can be encountered. As the location of the Meckel’s diverticulum varies among individuals, they are usually detected in the antimesenteric side of the ileum within 100 cm of ileocecal valve. Meckel’s diverticulum possesses various complication risks including intestinal obstruction, intussusception, inflammation and bleeding. Inversion of a Meckel’s diverticula is a scarse entity with a potential of intestinal obstruction due to direct luminal obliteration or causing a lead point for intussusception[6-8]. The pathophysiology of the disease process leads to a complicated and confusing clinical picture of recurrent obstructive symptoms, chronic abdominal pain and lower gastrointestinal bleeding that may cause a delay in diagnosis and waste time. In our case, we have detected a lipoma as a leading point of inversion which causes partial obstruction and bleeding. Recurrent partial obstructive periods and abdominal pain of our patient might be attributed to luminal obstruction due to inversion of Meckel’s diverticulum which might be induced by lipomatous development. An other possible mechanism for this symptomatology might be the probable intussusseptions according to the inverted diverticulum, which has been reported as a lead point previously[6,7]. Intestinal obstruction due to intussusception as a result of a lipoma within Meckel’s diverticulum has only been reported twice in literature[9,10]. Primary pathophysiologic process responsible for bleeding in Meckel’s diverticulum is the ileal mucosal ulceration due to the existence of heterotrophic gastric or pancreatic tissues which has not been verified in our patient; instead a subserosal lipoma has been demonstrated with ulceration and hemorrhage.

Lipomas of the small intestine are the second most common benign tumors next to leiomyomas[11]. Their location and the peak age vary, however approximately 50% were found in the ileum, and the sixth to seventh decades of life were considered to be the most risky period[4,11]. In general, lipomas are defined to originate in the submucosal layer and are usually solitary, with variable sizes ranging from 1 cm to 30 cm[12]. They usually appear as a sessile protrusion into the lumen of the intestine. Due to motor activity of underlying muscularis propria, they tend to extrude into the bowel wall or through the luminal area progressively, which might be the responsible reason for the inversion of the Meckel’s diverticulum in our case. In this manner, a pseudopedicle is formed, providing a polypoid appearance to the lesion. Although the majority of these lesions are asymptomatic and detected incidentally during the routine examinations or in surgical specimen removed for various other reasons, on rare occasions they might present with symptoms depending on their size and location. Lipomas smaller than 1 cm are generally incapable of producing symptoms, however 75% of lipomas with a size > 4 cm might give rise to gastrointestinal symptoms. Intestinal obstruction is one of the major result due to the occlusion of lumen by a large protruding lesion. Hemorrhage which is an other possible consequence might be based on an ulceration of the overlying mucosa caused by direct pressure from the lipoma or due to intussusception per se[4,12]. Preoperative diagnosis of small intestinal lipomas can be established by means of endoscopic and radiologic evaluation. Radiolucency and the so-called “squeeze sign” implying an altered configuration during peristalsis are suggestive findings observed in small intestinal series. Detection of fatty tissue density within the mass on CT scans supports the diagnosis. The “naked fat sign” which can be defined as the protrusion of fat through mucosal disruption following multiple biopsy sampling of the submucosal mass during endoscopic examination is believed to be pathognomonic[4,11].

Although more common in children, the complications of Meckel’s diverticulum have also been described in adults. Gastrointestinal bleeding and intestinal obstruction are the two most common clinical problems associated with Meckel’s diverticulum. Tumor within a Meckel’s diverticulum is a scarce clinical entity with a reported incidence of only 2%[13]. Intestinal obstruction caused by a lipoma within the Meckel’s diverticulum is so uncommon that we could only find three cases in the literature, two of which were due to intussusception[9,10], and one case of direct lumen occlusion by a large protruding lesion[14]. Moreover, the association of gastrointestinal hemorrhage and recurrent episodes of partial intestinal obstruction caused by a subserosal lipoma within an inverted Meckel’s diverticulum without the existence of heterotrophic gastric or pancreatic tissue is an exceptional case, which has not been reported over the last 40 years in literature.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Soderlund S. Meckel's diverticulum. A clinical and histologic study. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1959;Suppl 248:1-233. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Yahchouchy EK, Marano AF, Etienne JC, Fingerhut AL. Meckel's diverticulum. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:658-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Leijonmarck CE, Bonman-Sandelin K, Frisell J, Räf L. Meckel's diverticulum in the adult. Br J Surg. 1986;73:146-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fernandez MJ, Davis RP, Nora PF. Gastrointestinal lipomas. Arch Surg. 1983;118:1081-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | DeBartolo HM, van Heerden JA. Meckel's diverticulum. Ann Surg. 1976;183:30-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dujardin M, de Beeck BO, Osteaux M. Inverted Meckel's diverticulum as a leading point for ileoileal intussusception in an adult: case report. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:563-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Steinwald PM, Trachiotis GD, Tannebaum IR. Intussusception in an adult secondary to an inverted Meckel's diverticulum. Am Surg. 1996;62:889-894. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Konstantakos AK. Meckel's diverticulum-induced ileocolonic intussusception. Am J Surg. 2004;187:557-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ahmed HU, Wajed S, Krijgsman B, Elliot V, Winslet M. Acute abdomen secondary to a Meckel's lipoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:W4-W5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Formejster I, Mattern R. Ileus due to ileo-cecal intussusception caused by lipoma coexistent with Meckel's diverticulum. Wiad Lek. 1971;24:1101. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Olmsted WW, Ros PR, Hjermstad BM, McCarthy MJ, Dachman AH. Tumors of the small intestine with little or no malignant predisposition: a review of the literature and report of 56 cases. Gastrointest Radiol. 1987;12:231-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zografos G, Tsekouras DK, Lagoudianakis EE, Karantzikos G. Small intestinal lipoma as a cause of massive gastrointestinal bleeding identified by intraoperative enteroscopy. A case report and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2251-2254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Williams RS. Management of Meckel's diverticulum. Br J Surg. 1981;68:477-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Krespis EN, Sakorafas GH. Partial intestinal obstruction caused by a lipoma within a Meckel's diverticulum. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:358-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |