CASE REPORT

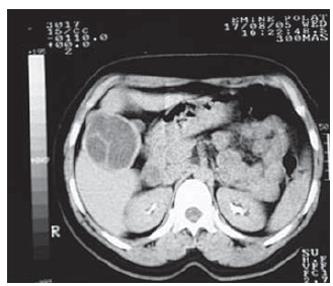

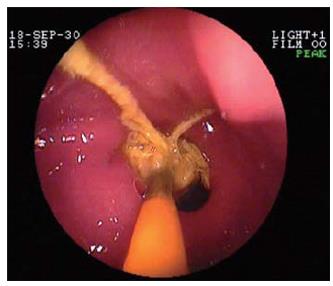

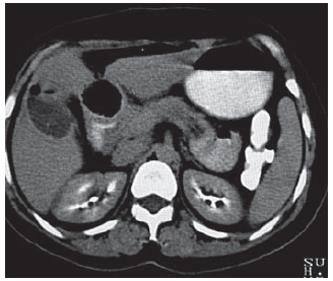

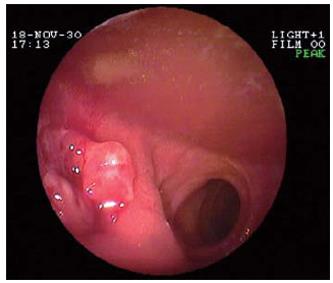

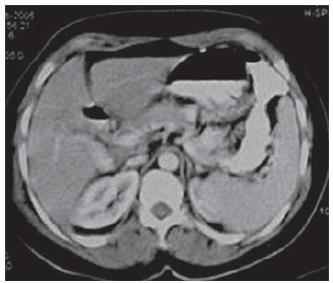

A 44-year-old woman was admitted with a complaint of abdominal pain that was present for the previous 15 d and was increasing in intensity, together with nausea. In her history she mentioned being operated on 2 mo previously for hydatic cyst, with cystotomy and drainage (Figure 1). On physical examination, there was epigastric pain and tenderness, and laboratory findings were not remarkable, other than for mild leukocytosis. Gastroduodenoscopy was performed for her gastric complaints. Upon endoscopy, a foreign body (gauze) that protruded from the pylorus to the antrum was identified. The gauze could not be retrieved after being approached by biopsy forceps and a polypectomy snare (Figure 2). In upper abdominal CT, there was a foreign body (3 cm × 3.5 cm) with intramural localization in the first and the second parts of the duodenum. It was surrounded by a thin wall, had a density with-600-700 HU (air density/air bubble), heterogeneous internal structure and was protruding in to the duodenum (Figure 3). As there was no free perforation, the decision was taken for conservative treatment, and proton pump inhibitors and liquid diet were recommended. The patient had a stable clinical course and was endoscopically followed-up at 5-d intervals. During the follow-up, the gauze slowly migrated to the lumen. On the fourth endoscopic examination, there was no gauze in the lumen, and there was an ulcerated area with a fistula opening in the middle at the same position (Figure 4). There was no foreign body observed on control CT (Figure 5). Upon questioning the patient, no information could be obtained about the passage of the gauze. Following 3 mo of medical treatment, all the symptoms were gone; upon control endoscopy, ulcer scar was observed on the bulbous.

Figure 1 Active hydatic cyst lesion in the liver seventh segment.

Figure 2 Gauze that could not be removed, despite being approached by biopsy forceps.

Figure 3 Lesion with a density-600-700 HU (air bubble) and heterogeneous internal structure, hypodense area in the liver pertaining to a postoperative cavity

Figure 4 Fistula opening on the anterior part of the

Figure 5 Control CT following the intraluminal migra-tion of the intramu-rally localized gauze in the first and the second parts of the duodenum.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of surgical sponge being retained during operation is difficult to estimate, but it has been reported as 1 in 100-3000 for all surgical interventions and 1 in 1000-1500 for intra-abdominal operations[4]. Retained sponges are most frequently observed in patients with obesity, during emergency operations[6] and following laparoscopic interventions[7]. Gossypiboma is most frequently diagnosed in the intra-abdominal cavity; however, it can also be seen in paraspinal muscles[8] and the intrathoracic region[9], legs[10] and shoulders[11].

Gossypiboma results in significant morbidity and possible mortality[5,12]. It can present itself as an intra-abdominal mass and might lead to erroneous biopsy attempts and unnecessary manipulations[13]. It commonly leads to misdiagnosis and unnecessary surgery[12]. Clinical presentation may be acute or subacute, and may follow months or even years after surgery[14]. Presentation of gossypiboma may vary and can be caused by pseudotumoral, occlusive or septic syndromes[5]. Of 14 patients with a diagnosis of gossypiboma, 13 were admitted with non-specific abdominal pain and intestinal obstruction. Four patients required emergency surgery due to intestinal obstruction or intra-abdominal sepsis[15]. Six patients with abdominal gossypiboma had symptoms of a mass, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention and pain. Three patients were diagnosed with intestinal obstruction and two with pseudotumoral syndrome[16]. If the patients do not recover in the postoperative period and are readmitted with extraordinary problems, gossypiboma should definitely be considered as the differential diagnosis in such cases[12]. During the period that gossypiboma remains in the body, extrusion of the gauze can occur externally through a fistulous tract or internally into the rectum, vagina, bladder or intestinal lumen[17]. By either fistulizing to a luminal organ or through direct migration, it can cause intestinal obstruction[18-21]. There are reports of spontaneous migration of the sponge from the colon or rectum in the literature[3,6].

There has also been a case report demonstrating the migration of endoscopically confirmed intra-abdominal gossypiboma through fistulization to a luminal organ. In addition to assisting with a definitive diagnosis, endoscopy can also be helpful in planning treatment[18]. The gauze that was endoscopically diagnosed in our case was found to have been corrected in the endoscopic follow-up, without necessitating surgical intervention.

They are mostly diagnosed by radiological methods in clinical practice. In radiological examinations, they are mostly seen as radio-opaque material, yet radiolucent material like sponges can cause diagnostic problems[3]. Plain radiographs suggest the diagnosis if a textile foreign body is calcified, that is, is equipped with a radio-opaque marker, or when a characteristic “whirl-like” pattern is present[22]. In the presence of radio-opaque markers, retained surgical sponges can be easily diagnosed by direct abdominal radiography; yet, if they penetrate and migrate inside the small bowel or bladder, it is difficult to localize them[20]. US images can be classified into two groups, a cystic type and a solid type[19]. US that shows a hyper-reflective mass with a hypoechoic rim, along with a strong posterior shadow, and CT that reveals a whirl-like spongiform pattern in a hypodense mass, with a thick peripheral rim, are considered the mainstay of investigation[5]. CT and US are necessary procedures in chronic cases, since the lesion may mimic a mass. CT usually reveals a hypodense mass with a thick peripheral rim[22]. Upper abdominal CT examination of our patient revealed a hypodense lesion surrounded by a regular capsule.

Surgery is the preferred method of treatment for gossypiboma. Of eight patients who were diagnosed 12 mo after initial surgery, seven were treated surgically and one was cured with spontaneous migration from the rectum[6]. One patient who developed perforation and an abscess because of migration to the ileum required surgery[7]. There have been rare case presentations like our own, in which total migration to a luminal organ results in recovery without requiring a second operation. However, we think that in the absence of free perforations, as in our case, and in the presence of migration to luminal organs, conservative treatment with clinical and radiological follow-up should be considered.

In order to prevent these types of complications, we need to abide by the rule of total control of all surgical material before and after surgery, which is the main principle in all procedures. Strict measures must be taken to prevent this complication.