INTRODUCTION

Cholangiocarcinomas (CCC) are rare malignant tumors arising from the biliary tract. According to their anatomic location they can be categorized as either intrahepatic or extrahepatic. Although intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) is less frequent than extrahepatic carcinoma, within malignant liver tumors it ranks second after hepatocellular carcinoma. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma differs considerably in different geographic regions, with the incidence highest in Southeast Asia[1]. In western countries ICC accounts for about 10% of primary liver malignancies with increasing incidence. Established risk factors for development of cholangiocarcinoma are liver fluke infestation especially with opisthorchis viverini, primary sclerosing cholangitis, hepatolithiasis, anomalous biliary-pancreatic malformation, choledochal cysts, thorotrast exposure, liver cirrhosis and hepatitis C infection[2]. However, most cholangiocarcinomas arise in the absence of known underlying risk factors.

The prognosis of ICC is very poor. Due to its intrahepatic localization, symptoms occur late in the course of the disease and patients often present with an advanced tumor. Most patients exhibit a median survival of less than 9 mo after diagnosis. To date, complete resection has been the only curative therapy. Recent trends are to advocate accurate preoperative staging with an aggressive surgical approach to achieve complete tumor resection[2,3]. In the majority of patients ICC presents at an advanced stage or patients have associated co-morbidity that preclude surgery. This patient group needs adequate palliation such as chemotherapy. Biliary decompression, which can be achieved by surgery, radiology or endoscopy, is an additional palliative treatment option. However, since ICC rarely cause biliary congestion, these additional palliative options are rarely used.

The importance of an optimal preoperative assessment of resectability and the lack of potent optional (adjuvant) therapeutic approaches, emphasize the necessity of novel prognostic and predictive parameters. This review focuses on the relevance of two central biological signaling pathways - namely the AKT and ERK1/2 pathway - in ICC. The development of phospho-specific antibodies for immunohistochemistry allows the evaluation of signaling activity of these pathways in pathological specimens. Phosphorylation of proteins either on specific tyrosine or serine residues is a posttranslational event modulating the activity of many key signaling molecules in the cell including AKT and ERK1/2[4]. We recently demonstrated AKT and ERK phosphorylation as an independent prognostic parameter in breast cancer and colorectal cancer, respectively[5,6]. Others found an association of AKT and ERK1/2 with decreased survival in various human malignomas including breast cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, malignant melanoma, leukemia and mucoepidermoid cancer[5,7-10]. This review describes the biological background of AKT and ERK in ICC, presents our own new data, analyses the potential prognostic relevance and discusses upcoming therapeutic options.

GENERAL BIOLOGY OF THE AKT AND ERK SIGNALING PATHWAYS

AKT/PKB (Protein kinase B)

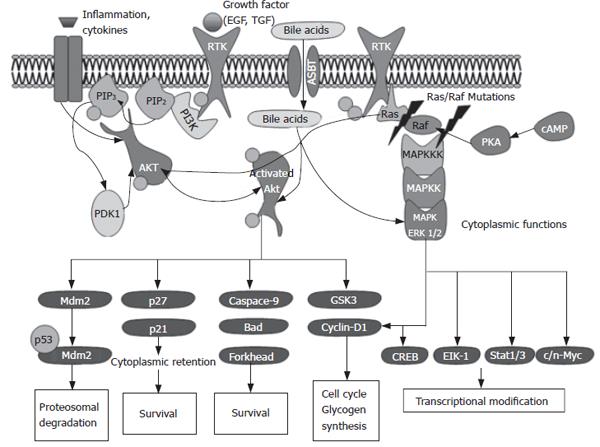

AKT is a central player in the regulation of metabolism, cell survival, motility, cell cycle progression and transcription. AKT is a serine/threonine kinase and its activation is induced by phosphorylation mediated by Phosphoinositide (PI) 3-kinase (PI3K) in association with tyrosine kinase receptors. The AKT family comprises three mammalian isoforms, PKBα, PKBβ and PKBγ (AKT1, AKT2 and AKT3, respectively), which are products from different genes and share a conserved structure. AKT includes three functional domains: an N-terminal pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, a central kinase domain, and a C-terminal regulatory domain. PI3K is localized upstream of the AKT kinase and is essential for the activation of AKT. PI3K and thereby AKT are activated upon (1) autophosphorylation of receptor tyrosine kinases induced by ligands (such as growth factors), (2) activation of cytokine receptors, (3) stimulation of G-Protein coupled receptors, or (4) activation of integrin signaling[11,12]. Upon PI3K mediated generation of the second messenger PtdIns (3,4,5) P3 AKT is translocated from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane. Once recruited to the membrane, AKT is activated by a phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 and 2 (PDK1, PDK2) dependent multistep process that results in the phosphorylation of both Threonine 308 and Serine 473 residues necessary for full AKT activation. Due to the great number of downstream substrates AKT kinase modulates a variety of central cellular processes as summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Overview of the AKT and ERK signaling pathway.

ERK (extracellular regulated kinases)

ERK1/2 - also referred to as p44 and p42 MAP kinases - are ubiquitously expressed kinases and represent one component of the three mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK) cascades that are activated by an enormous array of stimuli. The MAPK pathways phosphorylate and activate numerous proteins, including transcription factors, cytoskeletal proteins, kinases and other enzymes. Each of the three MAPK pathways contains a three-tiered kinase cascade comprising a MAP kinase kinase kinase (synonyms: MAPKKK, MAP3K, MEKK or MKKK), a MAP kinase kinase (synonyms: MPKK, MAP2K, MEK or MKK) and the MAPK. This review focuses on ERK1 and ERK2 that form a part of the MAPK module containing Raf MAPKKKs (A-Raf- B-Raf, C-Raf/Raf1) and the MEK1/MEK2 MAPKKs. All MAPKs are activated by dual phosphorylation of the conserved threonine and tyrosine residues. ERK1 and ERK2 are induced by stimuli such as tyrosine receptor kinases or G-protein coupled receptors. This leads to activation of Ras, which then triggers a complex network including the activation of Raf isoforms. ERK1/2 exhibit a variety of substrates including several key transcription factors (Figure 1). Depending upon the intensity and duration of stimulation ERK1/2 can result in proliferation of differentiation[13].

TARGETS OF THE AKT AND ERK PATHWAY

Both AKT and ERK mediate their effect via several substrates, which may be localized in the nuclei or in the cytoplasm. AKT can potentially phosphorylate over 9000 substrates in mammalian cells including typical cytoplasmic as well as nuclear proteins. Thus, AKT activity not surprisingly can be detected in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm[14]. When interpreting immunohistochemically stained tissue slides, it is important to keep the subcellular localization of activated AKT or ERK in mind. Moreover it seems as if both kinases show different subcellular localizations in various human carcinomas. In a colon cancer study, we showed pAKT immuno-localization in the nucleus and cytoplasm[6], in contrast to our results in ICC with a restricted immunoreactivity in the cytoplasm.

Cytosolic substrates for ERK include several pathway components involved in ERK negative feedback regulation. Multiple residues on SOS (son of sevenless homolog) are phosphorylated by ERK following growth factor stimulation. SOS phosphorylation destabilizes the SOS-Grb2 complex, eliminating SOS recruitment to the plasma membrane and interfering with Ras activation of the ERK pathway. It has also been proposed that negative feedback by ERK occurs through direct phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor EGF receptor at Thr669[15].

ERK1 and ERK2 regulate transcription indirectly by phosphorylating the 90 kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinases (RSKs), a family of broadly expressed Ser/Thr kinases activated in response to mitogenic stimuli, including growth factors and tumor-promoting phorbol esters[16]. Active RSKs appear to play a major role in transcriptional regulation, translocating to the nucleus and phosphorylating such factors as the product of proto-oncogene c-fos at Ser362, serum response factor (SRF) at Ser103, and cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) at Ser133[17,18]. Recent studies revealed a spatial control of ERK signaling by Sef (similar expression of FGF), a recently identified inhibitor, whose action mechanisms are not fully defined. Sef acts as a molecular switch for ERK signaling by specifically inhibiting nuclear translocation of ERK without inhibiting its activity in the cytoplasm[19]. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of Sef.

Upon phosphorylation, nuclear translocation of ERK1 and ERK2 is critical for both gene expression and DNA replication induced by growth factors. Probably the best-characterized transcription factor substrates of ERKs are ternary complex factors (TCFs) including Elk-1, which is directly phosphorylated by ERK1 and ERK2 at multiple sites[20]. Upon complex formation with SRF, phosphorylated TCFs transcriptionally activate the numerous mitogen-inducible genes regulated by serum response elements (SREs)[21]. Another direct target of ERK, at least in vitro, is the product of proto-oncogene c-myc, a short-lived transcription factor involved in multiple aspects of growth control[22].

AKT may mediate its functions both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus. AKT phosphorylates a great variety of substrates involved in the regulation of key cellular functions including cell growth and survival, glucose metabolism and protein translation. Most of the well-known targets are located in the cytoplasm but it is noteworthy that many of the substrates of AKT are proteins that function in the nucleus. Some relevant cytoplasmic targets of AKT are GSK3 (glycogen synthase kinase), IRS-1 (insulin receptor substrate-1), PDE-3B (phosphodiesterase-3B), BAD, human caspase 9, Forkhead and NF-B transcription factors, BRCA1, MDM2 (murine double minute), mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), eNOS (endothelial nitric oxide synthase), Raf protein kinase and p21Cip/Waf1. Several of these targets such as MDM2 translocate to the nucleus upon activation via AKT [23-28]. Similar to ERK1/2, immunohistochemical analysis of pAKT in various human cancers shows both cytoplasmic and nuclear immunoreactivity. In vitro studies showed that AKT is activated by membrane localization and later translocated to the cytosol and nucleus[29]. The function of nuclear activated AKT is not yet fully understood. Among the nuclear substrates there are fatty acid synthase[30], estrogen and androgen hormone receptors[31,32] and transcriptional factors of the FOXO family[33]. All these factors are supposed to increase cell survival.

SPECIAL ASPECTS OF AKT AND ERK IN CHOLANGIOCARCINOMA

Both the AKT and ERK pathways can be activated via several growth factors/survival factors, stimulation of G-protein-coupled receptors, or activation of integrin signaling. Due to the great array of activators relevant to different human cancers, we will focus on those activators that are likely to be specific for ICC.

Activation by growth factors

Both the AKT and the ERK pathway are inducible via growth factor stimulation. It is known that a subset of ICC exhibit overexpression of the EGF and HER-2 receptor[34]. Indeed, in our study group 21.3% (13/61) of ICC showed strong EGFR overexpression, which was confirmed by others[35]. Due to the relatively large subset of ICC with EGF or HER-2 expression activation of these ligands might be relevant for the progression of ICC.

Activation by cytokine receptors

A well-known risk factor for the development of cholangiocarcinoma is chronic inflammation. Chronically inflamed biliary epithelium is exposed to cytokines and chemokines. Indeed, cholangiocarcinoma cells constitutively secrete Interleukin 6 (IL-6), which is supposed to be a pivotal cytokine for cholangiocarcinogenesis[36-38]. A recent paper found ERK1/2 and AKT in cholangiocarcinoma cell lines to be activated via the cytokine receptor C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) via the CXC chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12). Thus, inflammation signals mediated by cytokine receptors are capable of inducing the ERK and AKT pathway[39].

Activation by oncogenes

It is crucial to know that AKT and ERK can be induced by mutation of oncogenes such as Ras and Braf. Ras is frequently mutated in many tumors, and is associated with constitutive activation of the ERK1/2 MAPKs. A recent study showed that in contrast to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), K-ras and Braf mutations are a frequent event in cholangiocarcinoma[40]. In fact 22% of the cholangiocarcinoma analysed exhibited a K-ras mutation and 45% a B-Raf mutation, respectively.

Since Ras and Braf proteins are members of the Ras/Raf/MAPKKK/MAPKK/MAPK pathway, activating mutations of K-ras and B-raf should result in increased activation of MAPK. Indeed it was shown, that tumors harboring a B-raf mutation exhibited stronger ERK1/2 immunostaining[40]. K-ras mutations are a frequent event in colorectal cancer and we recently demonstrated a consecutive activation of the ERK pathway in cancers with mutated K-ras[6]. These data indicate that frequent disruption of alterations in the Ras/Raf/MAPKKK/MAPKK/MAPK pathway, either by Ras or Braf mutations, may play a central role in cholangiocellular carcinogenesis.

Activation by bile acids

Cholangiocytes are exposed to high concentrations of bile acids. It is known that bile acids after cellular uptake by apical sodium bile acid cotransporter (ASBT), are capable of altering the AKT and ERK signaling pathways[41]. Moreover, the EGFR-pathway appears to be activated by extracellular bile acids via its ligand transforming growth factor TGF-alpha in cholangiocytes[42] and the human cholangiocarcinoma cell line[43]. The EGFR pathway, once activated initiates several signaling cascades, including the AKT and ERK pathways.

ERK AND AKT PATHWAYS AND PROGNOSIS

Little is known about the prognostic relevance of the ERK and AKT pathways in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. In fact, there is only one study that was based on a small cohort of 24 samples that does not discriminate between extra- and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma[44]. Thus, we aimed to elucidate the clinical impact of activated AKT and ERK pathways in a large and homogenous cohort of solely intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

We would like to present new data derived from a large study of 62 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Between 1998 and 2006 a total of 62 patients with a mean age of 58 ± 11.5 years were available for this study. The study comprised consecutive patients who underwent surgery for liver resection. Patients solely undergoing an explorative laparatomy without subsequent resection or with hilar cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder carcinoma or mixed hepato/-CCC were excluded from the study. The diagnosis of ICC was based on histology by examination of the resected liver specimen.

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY (IHC)

Phospho-AKT and Phospho-ERK

Immunostaining with pAKT (1/2/3) serine 473 was carried out with a monoclonal anti-phospho-AKT antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, Massachusetts, USA). Subsequent to antibody retrieval, the primary antibodies were incubated for 30 min at 1:20 dilution. Antibody detection was performed with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin and diaminobenzidine as chromogen. Tumors were classified according to their cytoplasmic staining intensity: negative (0), moderate (1) and strong (2).

Monoclonal phospho-p44/42 MAPK antibody (threonine 202/ tyrosine 204; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, Massachusetts, USA) was used at a 1:100 dilution. Tumor cells with strong specific immunostaining, independent of the amount of stained cells, were scored as strongly positive (2+). Tumors exhibiting a detectable but faint immunostaining were scored as weak (1+), whereas tumors with a minimal, hardly detectable or missing staining pattern were classified as negative (0).

EGFR

Immunostaining with EGFR was carried out with a monoclonal anti-EGFR antibody (Zymed Laboratories Inc, CA, USA). The primary antibodies were incubated for 30 min at 1:100 dilution. Antibody demonstration was achieved using the commercially available anti-mouse IgG detection kit (EnVision, DakoCytomation, Carpenteria, CA, USA). Classification was performed following the guidelines of PharmDxTm (DakoCytomation). Tumor samples lacking immunostaining were classified as negative (0), whereas the remaining were classified into 1+, 2+ or 3+ depending on the level of immunoreactivity.

Ki67 Immunostaining, TUNEL

The growth fraction was determined as previously described[45]. In situ DNA fragmentation was established using the terminal desoxyribonucleotide transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP nick end labelling technique (TUNEL) as previously described[45].

Statistical analysis

Immunostainings were assessed by two of the authors in a blind-trial fashion without knowledge of the clinical outcome. Interobserver agreement[46] of pERK and pAKT was substantial (kappa = 0.78 and 0.63). Relationships between ordinal parameters were investigated using two tailed χ2 analysis (or Fisher's exact test where patient numbers were small). Overall survival (OS) curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and any differences in the survival curves were compared by the log-rank test.

IHC of pAKT, pERK and EGFR

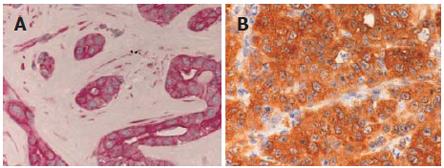

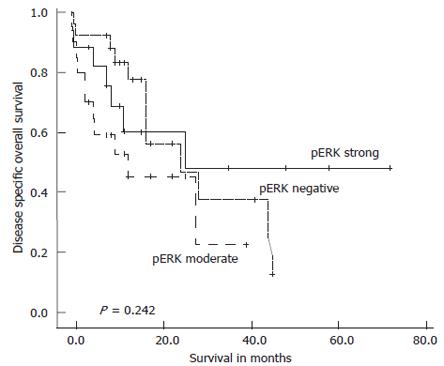

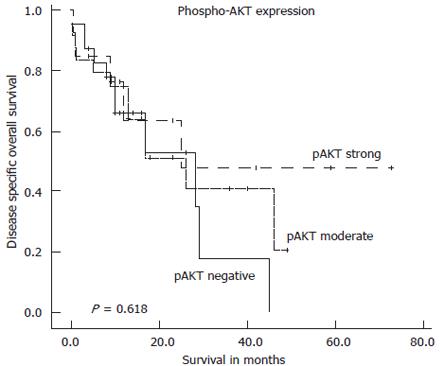

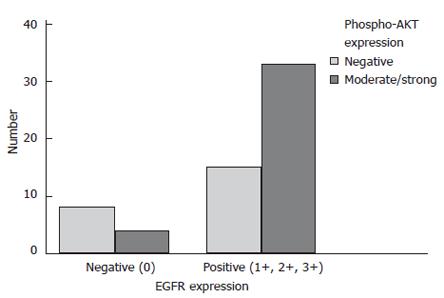

Immunostaining for pAKT was localized to the cytoplasm of tumor cells. Twenty two patients (37.3%) were classified as negative, 24 (40.7%) as moderately positive and 13 (22%) as strongly positive. Immunostaining of pERK exhibited a specific nuclear and cytoplasmatic staining pattern. Representative pAKT and pERK immunostainings are shown in Figure 2. In all, 26 (41.9%) tumors lacked pERK immunostaining, 19 (30.6%) tumors exhibited a moderate staining intensity and 17 (27.4%) tumors were classified as strongly positive. Immunostaining of EGFR was localized to the membrane of the tumor cells. Due to the lack of paraffin material, two cases were excluded from EGFR-IHC. In all, 12 (19.7 %) tumors were classified as negative, 19 (31.1 %) as 1+, 17 (28.9%) as 2+ and 13 (21.3%) as 3+. χ2 analysis revealed that EGFR-positive tumors (1+, 2+, 3+) had a statistically significant association with AKT activation (P = 0.028; Figure 5) but not with ERK activation. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis did not reveal a prognostic relevance of pAKT, pERK (Figures 3 and 4) or EGFR expression nor were any of the parameters associated with apoptosis or growth fraction (data not shown).

Figure 2 Light micrograph displaying strong phospho-ERK1/2 (A) and strong phospho-AKT (B) expression as analyzed by immunohistochemistry in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (x 400).

Figure 3 Kaplan-Meier survival plot for disease specific overall survival in the complete series of 62 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in relation to pERK immunostaining intensity.

Log-rank test: P = 0.242.

Figure 4 Kaplan-Meier survival plot for disease specific overall survival in the complete series of 59 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in relation to pAKT immunostaining intensity.

Log-rank test: P = 0.618.

Figure 5 Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with positive EGFR expression exhibit significantly more frequent AKT activation (χ2 analysis: P = 0.

028).

CONCLUSION

The ERK and AKT pathways are of central relevance and can induce growth factor independent growth, insensitivity to apoptotic signals, ability to invade and alter response to chemotherapeutic drugs. The fact that mutations of the Ras/Raf/MAPKKK/MAPKK/MAPK pathway occur in more than 60% of cholangiocarcinomas indicates the importance of these pathways for the carcinogenesis of cholangiocarcinomas and highlights new strategies in the treatment of this disease[47]. Moreover, the finding of a relatively large subset of ICC presenting overexpression of growth factors such as EGFR and HER-2/neu support the notion, that these growth factors play a relevant role in the progression of ICC. Our results support the notion that the AKT but not the ERK1/2 pathway is induced by EGFR overexpression, since we found a coexpression of pAKT and EGFR in ICC. However, neither ERK1/2 nor AKT activation influenced patient survival in this large series of ICC. Thus, both kinases may not serve as potential prognostic markers in this highly aggressive disease. Our results are in contrast to a previous study suggesting AKT as a favourable prognostic parameter in cholangiocarcinoma[44]. This study by Javle et al did not discriminate between intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and is based on a small cohort with 24 patients; thus, the data derived should be interpreted with caution. The main advantage of the present study is the large number of patients (n = 62) in combination with a high homogeneity of this series composed of consecutively resected ICC.

Both the AKT and ERK pathways are topics of preclinical and clinical trials. A promising candidate is the multikinase inhibitor Sorafenib, which inhibits several kinases including the Raf kinase, an upstream activator of the ERK pathway[48,49]. A recent study published the results of a phase II study of sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. It was demonstrated that HCC patients with higher pERK baseline levels had a longer time to progression following treatment with sorafenib thus pointing towards the possible relevance of activated pERK as an useful biomarker in HCC[48,49]. With regard to carcinomas of the biliary system the results of a phase II study of sorafenib in patients with unresectable or metastastic gallbladder carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma have been presented in Abstract form[50]. Sorafenib as a single agent did not result in a clinically significant objective response rate in patients with gallbladder and cholangiocarcinoma, but demonstrated an impact on survival that may be comparable to commonly used chemotherapy regimens. These promising data point towards novel therapeutic options utilizing multikinase inhibitors such as Sorafenib. In addition, the inhibition of upstream activators of the AKT and ERK pathways such as EGFR and HER-2 might also constitute novel therapeutic approaches. The results in a small number of patients showed that cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody against EGFR, is well tolerated and provides good palliative effects in advanced cholangiocarcinoma[51].

Despite the widely acknowledged potential of AKT inhibitors as anticancer therapy, few have made it to clinical trials. Wortmannin and LY294002 may have limited clinical utility owing to their lack of specificity, associated adverse effects, poor pharmacology, and poor solubility[52,53]. In vivo use of LY294002 in mice has been associated with many adverse effects, including death[54]. Furthermore, in mice, Wortmannin induces liver and bone marrow toxicity, and LY294002 can induce dermatitis and inhibit growth. Therefore, although Wortmannin and LY294002 inhibit the PI-3K/AKT pathway, their drawbacks raise doubts about their suitability as leading candidates for additional drug development.

Currently studies aimed at testing the clinical relevance of AKT inhibitors such as VQD-002, [Triciribine (TCN-P)] which is a tricyclic nucleoside that inhibits activated AKT, are being conducted. For example, the MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX (USA), and the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL (USA) have an ongoing Phase I/IIa clinical trial with VQD-002 in ovarian, pancreatic, breast, and colorectal cancer patients with tumors that over-express AKT (http://www.vioquestpharm.com/content/VQ0A002_about.html). Regarding the MAPK pathway, oral MEK inhibitors such as CI-1040 are currently being tested in a multicenter phase II study in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer[55].

In addition to the above-mentioned kinases, another potential therapeutic target is worth mentioning. Against the background of NSAIDs, recent studies have evaluated selective COX-inhibitors for their effect on cell growth and invasion of cholangiocarcinoma cells in vitro and in nude mice[56-60]. Treatment with COX-2 inhibitors resulted in induced apoptosis and inhibited proliferation. In a recent study we demonstrated the independent prognostic value of immunohistochemical COX-2 protein expression in resected ICC[45], thereby offering a further potential additional adjuvant therapeutic approach with COX-2 inhibitors facilitating an optimised therapeutic strategy. Moreover COX-2 may serve as a target for chemoprevention in high-risk patients.

Significant progress has been made in understanding this disease, and patients are being diagnosed earlier at specialized centers. Moreover, an optimized preoperative assessment of resectability as well as an aggressive intraoperative approach to achieve complete tumor resection might increase long-term survival[3]. However, a significant proportion of patients present with advanced disease and are not candidates for curative surgery. The palliative options, mainly consisting of chemotherapy, are of limited benefit, as cholangiocarcinomas respond poorly to existing therapies. Therefore, further clinical and preclinical trials are necessary in order to develop novel therapeutic options based on new tumor targets such as AKT, ERK and EGFR. Although the activation of these pathways did not show an impact on survival in ICC - at least in this study - in contrast to many other human carcinomas, an interruption of these pathways or associated signaling molecules by specific inhibitors might, nevertheless, have favorable effects on long-term survival for this highly aggressive cancer.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Roberts SE E- Editor Liu Y