TEXT

The good news is that the annual incidence of acute hepatitis C has fallen in recent years, primarily because of effective blood and blood product screening efforts and increased education on the dangers of needle sharing. The bad news is that there are no approved therapies for treating patients with acute hepatitis C and most patients infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV) are unaware of their exposure and remain asymptomatic during the initial stages of the infection, making diagnosis difficult and often surprising for the patient. However, there is a subset of patients - mainly healthcare workers - who have documented exposure as a result of a needle stick accident. These patients are subsequently monitored within surveillance programs to establish a documented conversion from HCV RNA-negative to HCV RNA-positive status[1]. While HCV accounts for only a minority of cases of acute hepatitis, it is the primary cause of chronic hepatitis and liver disease. With more than 170 million chronic hepatitis C patients worldwide[2] and an alarming increase in the related morbidity and mortality projected for the next decade[3], an improvement in our ability to diagnose and treat patients with acute hepatitis C would have a major impact on the prevalence of chronic hepatitis and its associated complications worldwide.

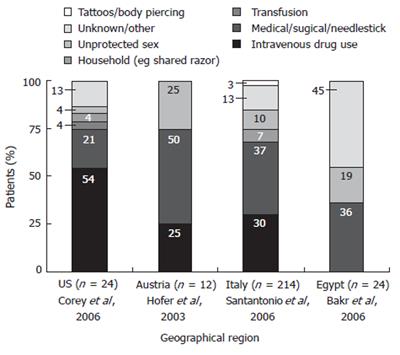

Because most acute hepatitis C patients remain undiagnosed and there is a relatively high rate of spontaneous resolution of HCV infection, little is known about the epidemiology of acute hepatitis C. Robust epidemiological data is available only for those patients who progress to chronic infection, develop symptoms, and/or seek treatment. However, what we do know about the epidemiology of acute hepatitis C is that intravenous drug and surgical/accidental exposure have been identified as the most common route of HCV transmission in most studies conducted in Western populations (Figure 1). Indeed, intravenous drug use accounted for about 25% to 54% of acute cases of hepatitis C in studies conducted in the US and throughout Europe[4-7]. In the United States alone, almost half of all HCV-positive patients aged 20 to 59 years report a history of injection drug use[8]. Transfusion-related acute hepatitis C is relatively rare; however, blood transfusion prior to 1992 remains a significant risk factor for hepatitis C infection throughout the world[8]. Sexual contact is another important route of transmission (risk factor 4% to 25%)[4-6]. Individuals with 20 or more lifetime sexual partners are at significant risk for hepatitis C in Western Countries; those participating in high risk sexual behavior are particularly susceptible because of an association with herpes simplex-type 2 infection[2,8]. In other geographic areas, social and cultural differences combine to produce a very different set of risk factors for hepatitis C. In Egypt and other African nations, illicit drug use is almost non-existent and infection mainly occurs via blood transfusion, or through nosocomial exposure (surgery or during circumcision)[9]. Intrafamilial exposure is also a primary route of transmission in rural Egypt[10].

Figure 1 Acute hepatitis C sources of infection by geographic region.

Unfortunately, there is no universally agreed-upon diagnostic criteria for acute hepatitis C; a series of clinical features generally leads us to suspect acute HCV infection[11]. These ‘characteristics’ include an acute increase in alanine aminotransferase levels to more than 10 times the upper limit of normal (with or without an increase in bilirubin) and an exposure to HCV during the previous 2-12 wk coupled with subsequent detectable HCV RNA. The few patients with acute hepatitis C who display symptoms may complain of constitutional problems or jaundice[12]; however, even among these symptomatic patients, jaundice is not always evident and slight fatigue may be the only indication that infection has taken place[13].

In many patients, HCV infection is self-limiting and spontaneously resolves before proceeding beyond the acute phase. However, establishing just how many cases resolve before reaching the chronic status has proved difficult because so few cases are actually detected. Estimates of spontaneous resolution range from 10% to 60%[1,14]; conversely, 43% to 86% of cases are thought to result in chronic infection[13]. Although these estimates vary widely, a general rule of thumb is that 20% to 26% of patients with acute hepatitis C experience spontaneous resolution[11,15]. Spontaneous resolution is most likely during the first 3-4 mo after infection; after 6 mo, it rarely occurs. So, we generally consider the first 6 mo after infection as “acute hepatitis C” and anything thereafter, “chronic hepatitis C”.

Several clinical features - including the presence of symptoms and the patient’s sex, immune status, and age - can serve as useful predictors of spontaneous resolution in patients with acute hepatitis C. Robust and multispecific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses are closely associated with recovery, suggesting that patients with strong immune systems have a better chance of controlling the infection[1,11]. Additionally, patients less than 40 years of age are more likely to undergo spontaneous resolution. Interestingly, infants with HCV infection have a 75%-100% chance of spontaneous resolution[11]. Conversely, patients with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV or solid organ transplant recipients, experience more frequent progression to chronic infection[11]. Finally, self-limiting disease is also significantly more common in women than men (40% vs 19%, P < 0.01) possibly due to the facilitation of HCV clearance by an estrogen-dependent mechanism[15].

There are no currently approved treatments for acute hepatitis C; however, recently published clinical trials can be used as a basis for establishing successful management strategies. Monotherapy with standard interferon (IFN) alfa-2b or pegylated IFN (PEG-IFN) alfa-2b for 24 wk have both been shown to be effective treatments. For example, an induction regimen of IFN alfa-2b (5 MU daily for 4 wk and then 3 times weekly for 20 wk) yielded a sustained virologic response (SVR) rate of 98% in one study[16]. Similarly, 89%-95% of patients receiving PEG-IFN alfa-2b monotherapy (1.5 μg/kg per wk for 12 to 24 wk) successfully achieved viral eradication[17,18]. With both regimens, an 8-12 wk observation period between exposure to HCV and initiation of therapy is important to allow for the possibility of spontaneous resolution.

In conclusion, acute hepatitis C is a rarely encountered clinical entity. Although it is usually asymptomatic and often resolves spontaneously, it also represents an important window in the time course of this infection during which medical intervention is greeted with a high degree of success. Efforts to increase awareness, improve diagnosis, and facilitate treatment of acute hepatitis C will have far reaching implications for the management of chronic hepatitis C, where current disease management and health outcome strategies are less effective.