Published online Dec 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i47.6404

Revised: September 16, 2007

Accepted: November 15, 2007

Published online: December 21, 2007

AIM: To assess the importance of preoperative diagnosis and presentation of left-sided gallbladder using ultrasound (US), CT and angiography.

METHODS: Retrospective review of 1482 patients who underwent enhanced CT scanning was performed. Left-sided gallbladder was diagnosed if a right-sided ligamentum teres was present. The image presentations on US, CT and angiography were also reviewed.

RESULTS: Left-sided gallbladder was diagnosed in nine patients. The associated abnormalities on CT imaging included portal vein anomalies, absence of umbilical portion of the portal vein in the left lobe of the liver, club-shaped portal vein in the right lobe of the liver, and difficulty in identifying segment IV. Angiography in six of nine patients demonstrated abnormal portal venous system (trifurcation type in four of six patients). The main hepatic arteries followed the portal veins in all six patients. The segment IV artery was identified in four of six patients using angiography, although segment IV was difficult to define on CT imaging. Hepatectomy was performed in three patients with concomitant liver tumor and the diagnosis of left-sided gallbladder was confirmed intraoperatively.

CONCLUSION: Left-sided gallbladder is an important clinical entity in hepatectomy due to its associated portal venous and biliary anomalies. It should be considered in US, CT and angiography images that demonstrate no definite segment IV, absence of umbilical portion of the portal vein in the left lobe, and club-shaped right anterior portal vein.

- Citation: Hsu SL, Chen TY, Huang TL, Sun CK, Concejero AM, Tsang LLC, Cheng YF. Left-sided gallbladder: Its clinical significance and imaging presentations. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(47): 6404-6409

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i47/6404.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i47.6404

Left-sided gallbladder is defined as a gallbladder located to the left side of the ligamentum teres. This anomaly can be divided into three anatomic abnormalities: a situs inversus, an ectopic left-sided gallbladder, and a right-sided ligamentum teres[1-4]. Left-sided gallbladder with right-sided ligamentum teres has been a rare anomaly since Hochstetter’s first description in 1886. Its characteristic description is a “gallbladder lying over the left side of the ligamentum teres”[1,4,5]. The associated anomalies with left-sided gallbladder include portal vein anomalies, biliary system anomalies, and segment IV atrophy[5-9]. The complex anomalies associated with left-sided gallbladder are important during hepatectomy, particularly in living donor liver transplantation. Preoperative survey of the anomalies of the portal triad is important in minimizing the incidence of postoperative biliary and vascular complications. Unknowingly, ligation of the left branch of the portal vein and bile duct that contribute to three-quarters of the liver hemodynamics will cause hepatic failure, biliary congestion and leakage[7,8,10-12]. This series reports nine cases of left-sided gallbladder with right-sided ligamentum teres. Its associated anomalies and significance during hepatectomy are identified and discussed.

We reviewed 1528 enhanced CT scans performed for survey of liver tumors, other abdominal tumors, retroperitoneal tumors and abdominal pain at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan from 1999 to 2004. Forty-six patients were excluded because the gallbladder position or fossa could not be determined from previous hepatectomy or cholecystectomy. Of the remaining 1482 patients, nine were diagnosed to have left-sided gallbladder due to the presence of a right-sided ligament teres on enhanced CT. Among these patients, one underwent right hepatectomy and cholecystectomy for segment IV hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The other two patients underwent left lateral segmentectomy and partial hepatectomy for left lateral segment HCC, respectively.

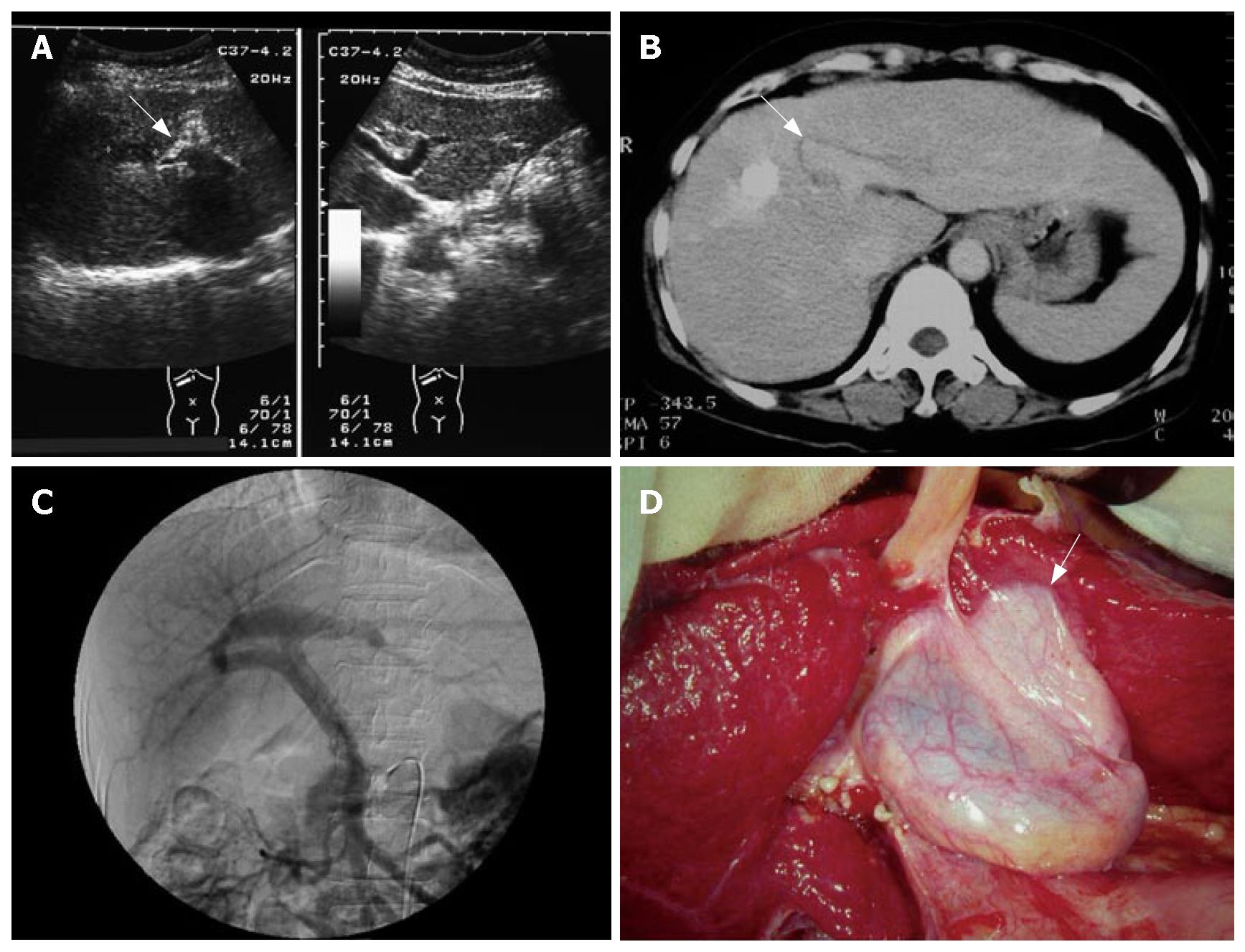

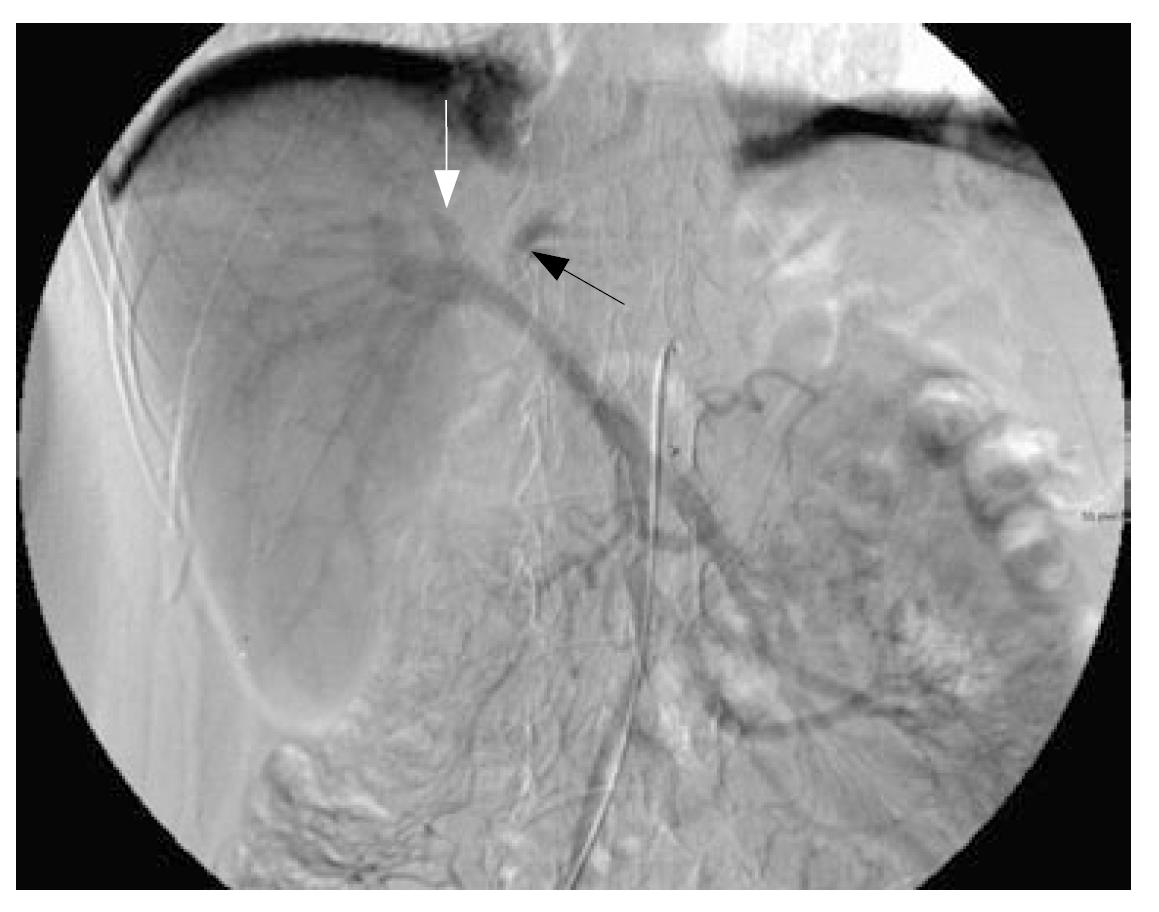

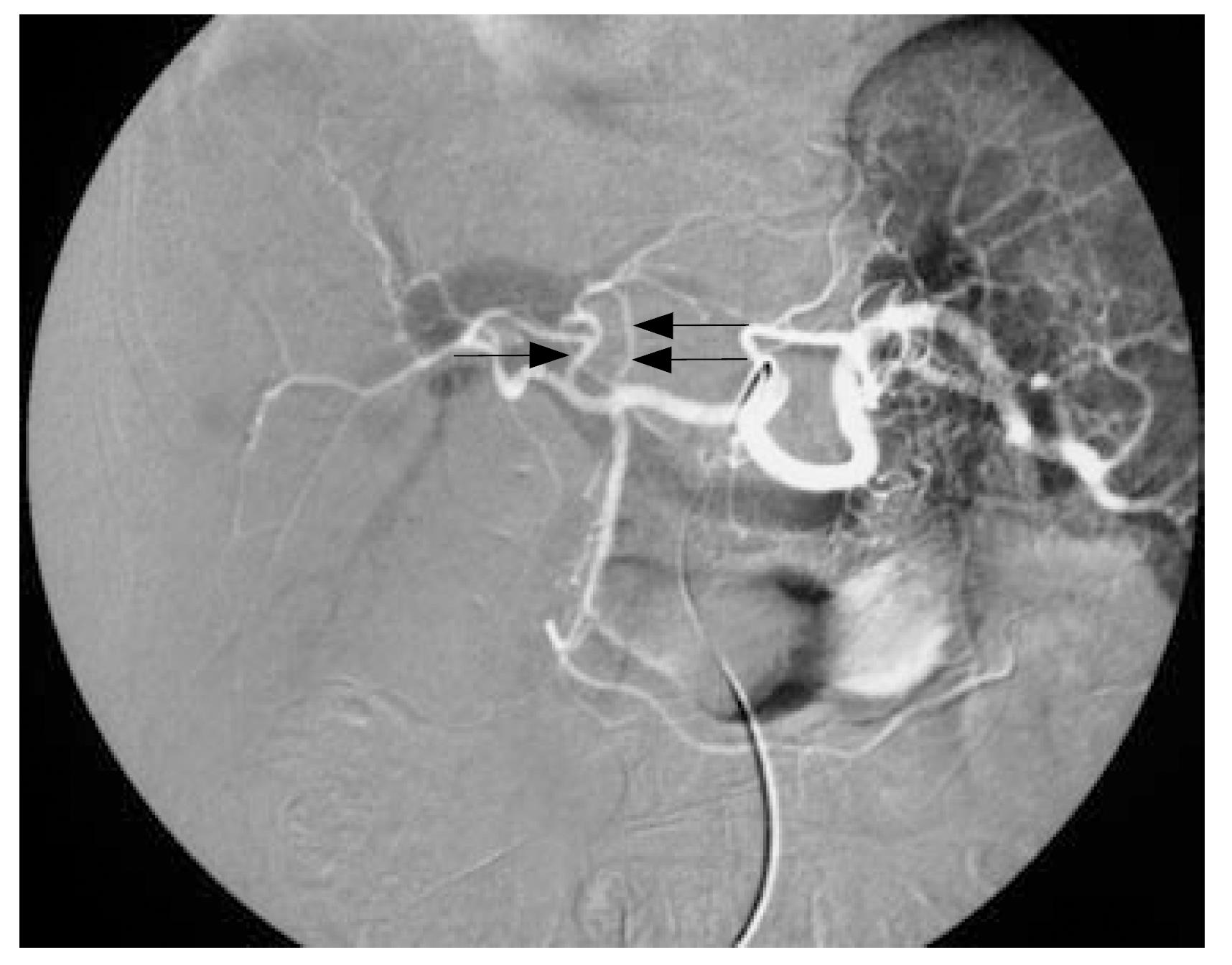

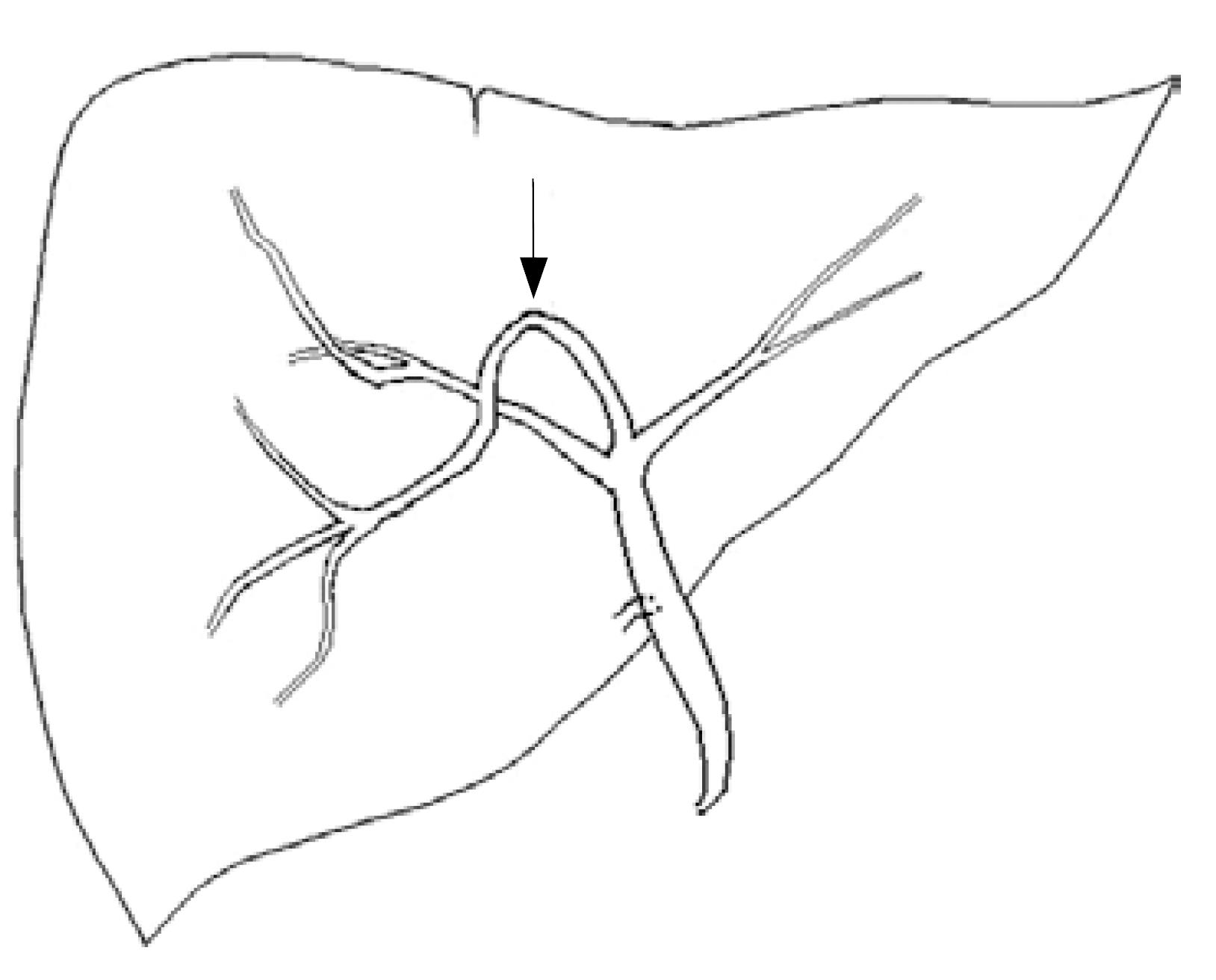

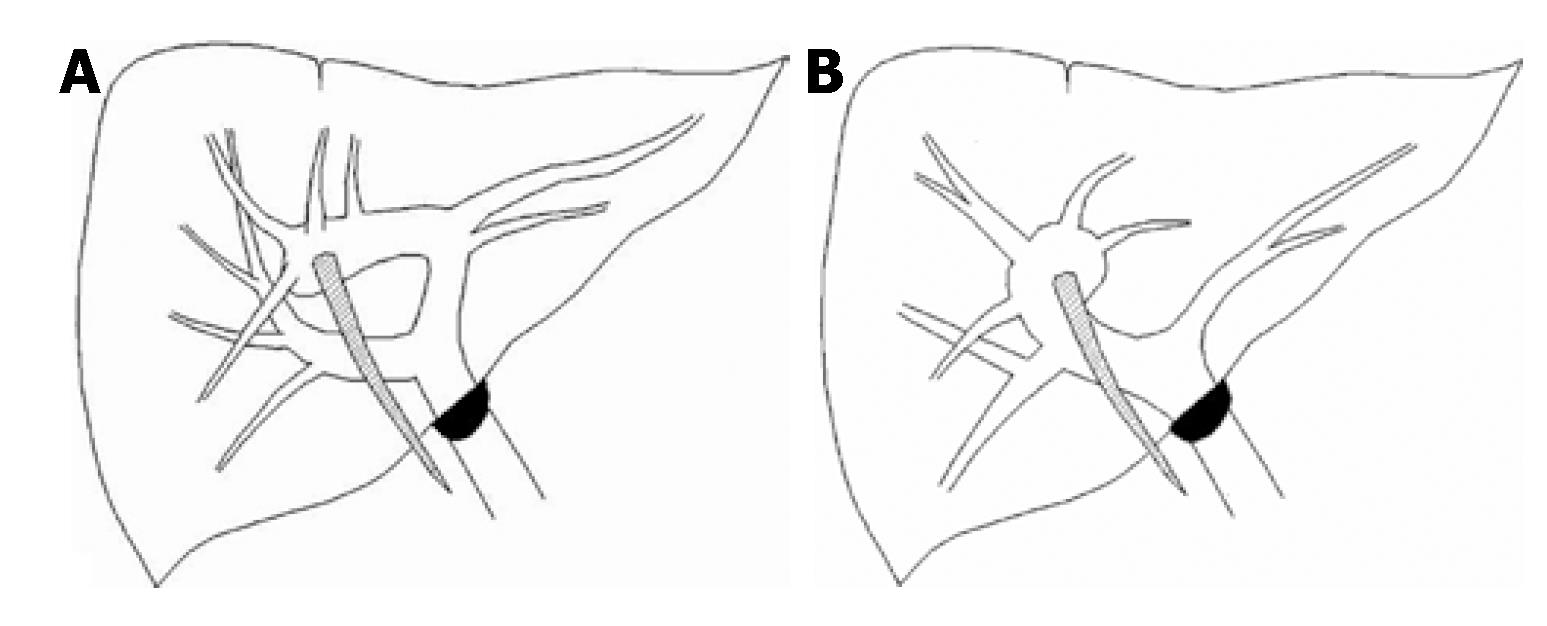

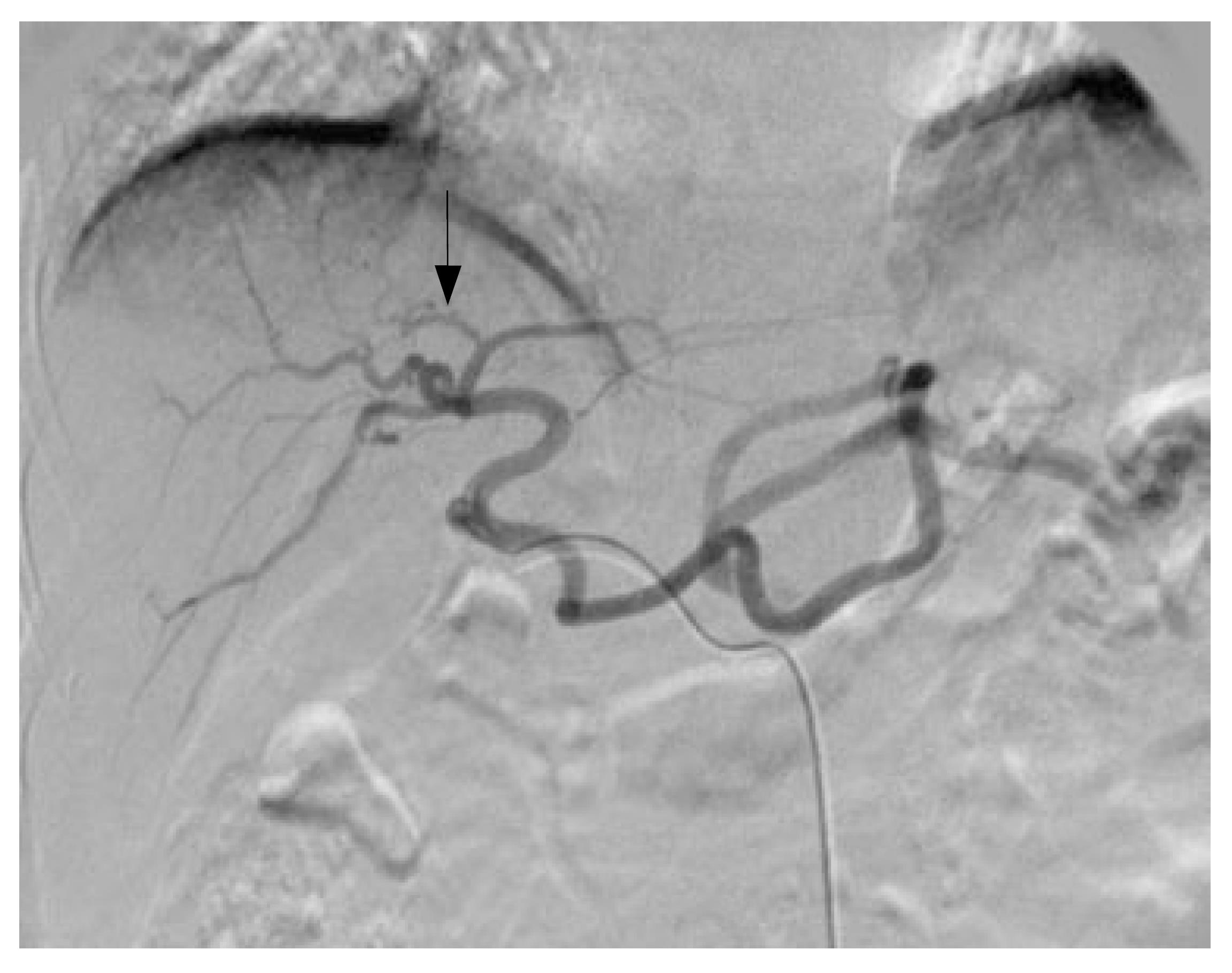

Nine patients from a screening population of 1482 patients (0.6%) were diagnosed with left-sided gallbladder with enhanced CT. Ultrasound (US) was performed in eight of the nine patients, and angiography was done because of liver tumors in six patients. The clinical status and imaging findings are listed in Table 1. US demonstrated no umbilical portion of the portal vein over the left lobe of the liver in eight patients, of whom, four had an abnormal club-shaped portal vein over the right side of the liver (Figure 1A), whereas the other four patients did not clearly show a dilated portion of the portal vein on the right side of the liver. Enhanced CT demonstrated absence of the umbilical portion of the portal vein over the left lobe of the liver, and an abnormal umbilical portion of the portal vein over the right lobe of the liver, as in the US findings. Segment IV of the liver was difficult to define on CT imaging in all nine patients (Figure 1B). Angiography was performed in six of the nine patients. In four patients, the portal veins ramified to the right and left portal tributaries, and the left tributary of the portal vein diverged into lateral and medial portions. The medial portion veered to the ventral side and formed the umbilical portion, which finally joined the ligamentum teres (trifurcation type) (Figure 1C). The other two patients had the portal veins ramified to the right, and small left portal tributaries. In these patients, the right portal vein formed the umbilical portion with some tributaries, and finally joined the ligamentum teres. The type of portal vein ramification could not be defined from conventional descriptions in these two patients (Figure 2).The main hepatic arteries ran alongside with the main portal venous tributaries in all six patients, of whom four had well-defined segment IV artery (Figure 3). One patient underwent right hepatectomy and cholecystectomy due to HCC over the right lobe of the liver. Another two patients receive left lateral segmentectomy. In these cases, the left-sided gallbladder was well-demonstrated intraoperatively (Figure 1D).

| Patient number | Clinical status and history | Club-shaped form portal vein (ultrasound finding1) | Left lateral segment of liver (computed tomography finding2) | Segment IV artery (angiogram finding) | Portal vein configuration (angio-portogram finding) |

| 1 | HCV, HCC, right hepatectomy | Over right lobe liver | Hypertrophic | From RHA | Trifurcation type |

| 2 | HCC, HBV and HCV | Not clear | Normal size | Not obvious | Other type |

| 3 | Right lobe HCC | Over right lobe liver | Mild hypertrophic | From RHA | Trifurcation type |

| 4 | Right lobe HCC, HBV | Over right lobe liver | Normal size | > From RHA | Trifurcation type |

| 5 | Hysterectomy, abdominal pain | Not clear | Normal size | NA | Not available |

| 6 | Liver tumor, HBV | Not clear | Mild hypertrophic | NA | Not available |

| 7 | Multiple HCC | Over right lobe liver | Normal size | NA | Not available |

| 8 | HCC, left lateral partial segmentectomy | Not clear | Normal size | From LHA | Trifurcation type |

| 9 | HCC, left lateral segmentectomy | NA | Normal size | Not obvious | Other type |

Left-sided gallbladder with right-sided ligamentum teres is rarely reported. However, with advances in diagnostic imaging modalities, such as US, CT, MRI and angiography, left-sided gallbladder is increasingly being reported to be associated with right-sided ligamentum teres, accompanied by abnormal intrahepatic portal venous branching. An initial impression of left-sided gallbladder is made when the ligamentum teres is deviated to the right side, and a right-sided umbilical portion of the portal vein is present with difficulty in defining segment IV anatomy[5,6,8]. Our survey of nine cases is the largest report to date, and revealed an incidence of 0.6% of this anomaly, which is consistent with the previously reported incidence of 0.1%-1.2%[5,7,8,13,14].

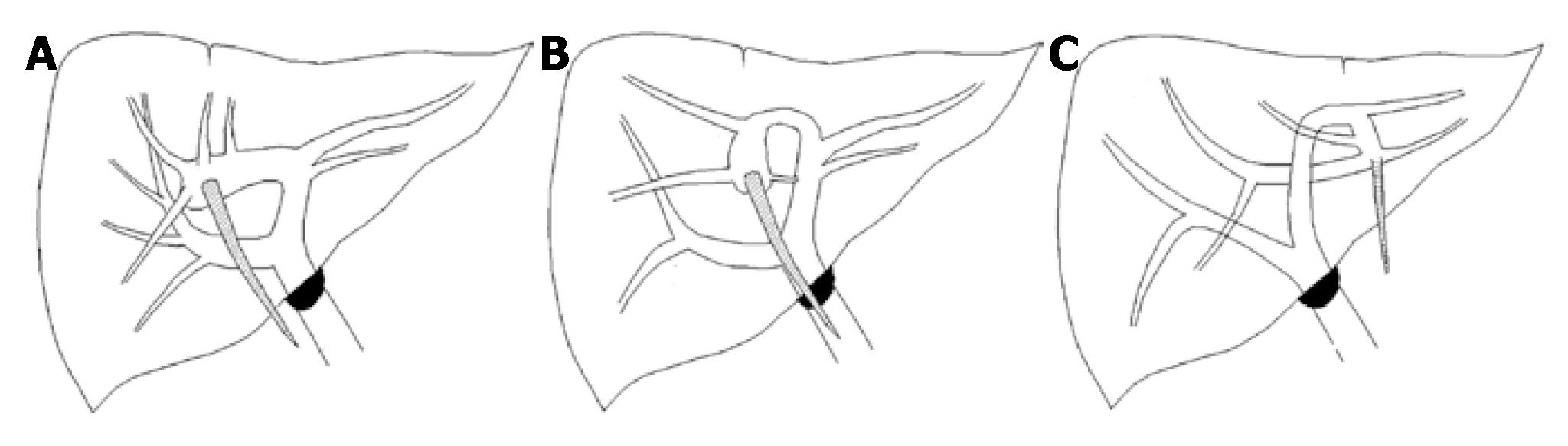

There are several explanations for the development of left-sided gallbladder without situs inversus. First, the normal gallbladder bud may migrate to the left lobe instead of the right, and lies on the left side of the ligamentum teres[15]. In this situation, the portal vein, biliary tree and hepatic artery should be in the normal location and classified into ectopic gallbladder. Second, the gallbladder may develop directly from the left hepatic duct, and is accompanied by failure in development of the normal structure on the right side[7,15]. Our literature review showed[5-7,11,15,16] only one case of left-sided gallbladder in which the cystic duct originated from the left hepatic duct[16]. The proposal of left-sided gallbladder development due to a second gallbladder originating directly from the left hepatic duct was not favored in those cases. Third, the left umbilical vein disappears and right umbilical vein partly remains. The peripheral (or placental) and central portions of the latter develop into the ligamentum teres and ligamentum venosum, respectively (Matsumoto's hypothesis)[13,17]. According to this hypothesis, the right umbilical portion should lie to the right of the gallbladder bed, but the gallbladder bed lay astride the ligamentum teres, as reported in four previous cases[7,18]. Nevertheless, this explanation also does not fit with our cases. Fourth, the gallbladder is on the left side of the ligamentum teres simply because the latter deviated to the right[5,7,16]. Maetini et al[7] have stated that there are three types of portal vein anomalies with the umbilical portion supplying the right anterior portion. In type A, the umbilical portion is to the right of the Cantlie line, whereas the umbilical portion lies on and to the left of the Cantlie line in types B and type C, respectively (Figure 4). They have also found that in the cases of left-sided gallbladder, the right posterior segmental duct joins the common duct distal to the bifurcation, and the aberrant right anterior segmental duct lies in the groove for the ligamentum teres, at which it forms a reverse U-shaped segment similar to the portal vein (Figure 5). They believe that the gallbladder on the left side of the ligamentum teres is there simply because the latter deviated to the right. As the right lobe of the liver becomes atrophied, we propose that the ligamentum teres moves from the left (type C) to the right (type A). The gallbladder moves to the left of the ligamentum teres, and the umbilical portion occupies the right side of liver.

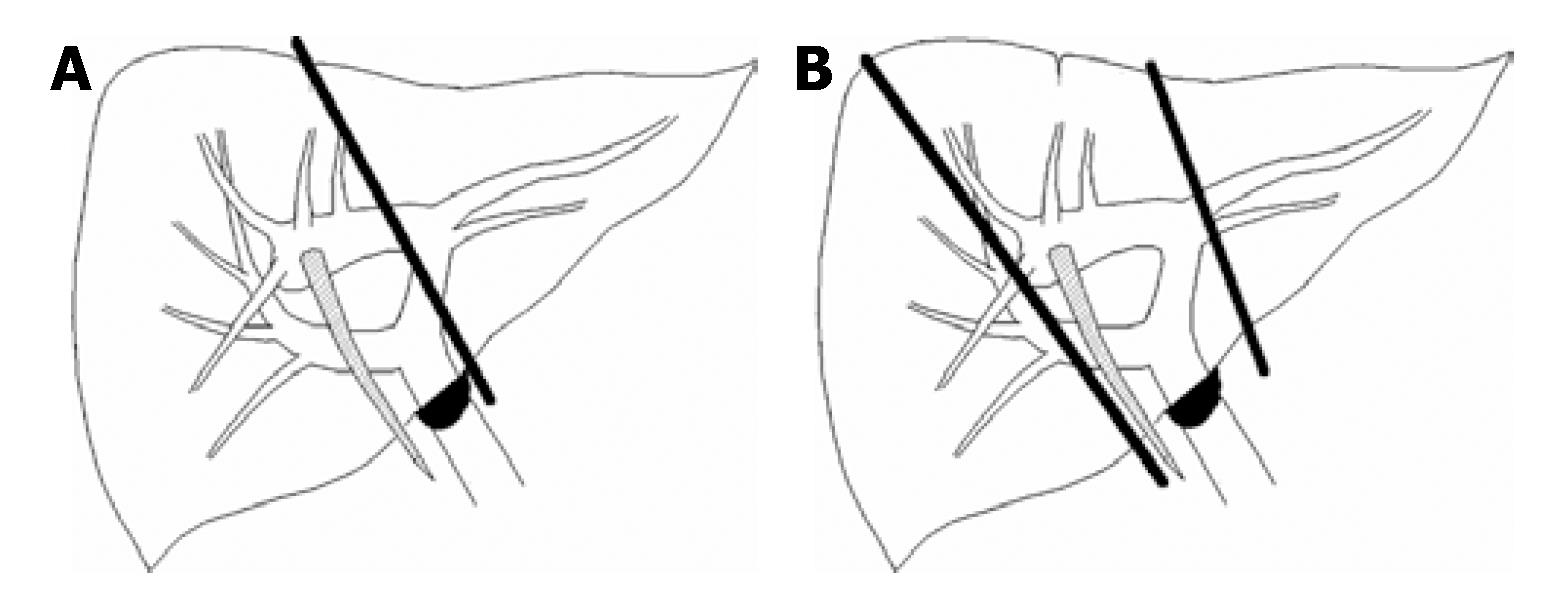

Left-sided gallbladders have previously been reported to be associated with portal vein anomalies, biliary system anomalies, and segment IV atrophy. The associated portal vein anomalies are significant in hepatectomy, split liver transplantation, or living donor liver hepatectomy in transplantation, and can be classified into three types: the trifurcation type, bifurcation type and the other type, in which portal vein ramification cannot be defined from conventional descriptions (Figure 6)[5,19]. Intrahepatic arteries in left-sided gallbladders have not previously been described in detail[2,5]. In principle, the hepatic arteries follow the portal venous tributaries but the hepatic arterial variations and dissociation between the intrahepatic bile duct and portal vein have been reported[5,11,20,21]. In our six patients, in general, the hepatic arteries followed the portal venous tributaries (Figure 3). Angiography demonstrated the segment IV hepatic artery (Figures 3 and 7) in four of six patients, although segment IV was difficult to define on CT imaging. Segment IV atrophy is unlikely and we believe that the segment is embedded in the right lobe of the liver, and the true right lobe of the liver is relatively hypoplastic. Hypoplasia of the right lobe of the liver contributes to the ligamentum teres and umbilical portion being deviated to the right and therefore, causing a left-sided gallbladder. The dividing line between segment IV and the right lobe of the liver was not visualized, while segment IV was embedded in the right lobe of the liver. Although biliary tree anatomy was not evaluated in our patients, the bile duct and arterial branches appear to follow the portal venous tributaries of left-sided gallbladders[5,7,8,11]. If segment IV is embedded in the right lobe of the liver, the segment IV bile duct originated from left main intrahepatic duct ran downward and ventrally formed a reverse U-shaped right anterior segmental bile duct because of the intrahepatic duct following the portal vein. The segment IV bile duct can reasonably explain the formation of a reverse U-shaped right anterior segmental duct that joins the left hepatic duct and lies in the groove for the ligamentum teres, as reported by Maetani et al and Newcombe et al[7,22,23].

A left-sided gallbladder is an important entity during liver resection, particularly in left hepatectomy for tumors, complicated hepatolithiasis, and in liver transplantation[7,8,24]. Our experience of one patient who underwent hepatectomy for liver tumor in the segment IV with diagnosis of left-sided gallbladder and trifurcation type of portal vein anomaly aided in planning for resection (Figure 1A-D). As a result, an extended right instead of a left hepatectomy was performed. If this anomaly had not been recognized preoperatively, left hepatectomy could have been performed, and the portal vein supplying three-quarters of the liver may have been ligated, leading to hepatic failure, biliary congestion or bile leakage[7,8,11,12]. In two other patients, a tumor was located over the lateral segment; left hepatectomy was considered risky and only a left lateral segmental or partial hepatectomy was acceptable in both cases (Figure 8). All patients were discharged uneventfully post-hepatectomy.

Prior knowledge of a left-sided gallbladder is also important in living donor liver transplantation. In right lobe living donor liver transplantation, right lobe graft harvesting encounters double right portal veins in a patient with a left-sided gallbladder. Hepatic venoplasty or vein graft interposition for the reconstruction of the portal veins must be performed, thereby contributing to the complexity of surgery. In left lobe living donor liver transplantation, left-sided gallbladders with trifurcation-type portal vein anomaly are more technically demanding because only the left lateral segment can be used, and separation of the right anterior portal and left portal vein is mandatory[12,25-27]. The volume of the left lateral segment instead of the whole lateral lobe is calculated to determine left liver volume suitable for donation. In some cases, there is no common trunk of the left portal veins, which leads to difficulty in portal vein reconstruction and the possibility of portal vein thrombosis[8].

Anatomical variations associated with left-sided gallbladders are also important in split liver trans-plantation[12,25-27]. There are two ways of splitting the liver parenchyma suitable for transplantation: (1) dividing the right and left lobes of the liver into anatomical right or left lobes; and (2) separating the liver between the left medial segment and left lateral segment. During division of the right and left lobes of the liver, the portal venous pedicle is separated at the hepatic hilar region, with the left portal vein free and the right portal vein continuous with the main portal vein, or the double right portal veins free and the left portal vein continuous with the main portal vein. Hepatic venoplasty or vein graft interpositions are necessary to reconstruct these anomalous vessels. When separating the liver between the left medial and left lateral segments, the portal venous pedicle is usually divided at the hepatic hilar region, with the left portal vein free and the right portal vein continuous with the main portal vein. This conventional approach can preserve the right lobe, but the volume of left lateral segment may not be sufficient for donation from donors with a left-sided gallbladder. Preoperative evaluation of the left lateral segment volume is, therefore, critical in donors with a left-sided gallbladder.

Right anterior hepatic duct joining the left hepatic duct is a common variation in left-sided gallbladders. Its angle is too acute for possible dilatation in the treatment of the postoperative residual hepatolithiasis, with eventual stenting through the T-tube tract. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotomy via the left intrahepatic duct should be considered and can provide a more favorable anatomy[24,28,29]. Left-sided gallbladders are overlapped by both the ligamentum teres and falciform ligaments, as well as by the left lobe of the liver. Although laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed with the standard port sites with a falciform lift, more medial positioning of the gallbladder-retracting port, and placement of the right-hand operating port to the left of the midline is suggested for laparoscopic removal of left-sided gallbladders[6,30,31].

In conclusion, left-sided gallbladders are a rare anomaly. Judicious preoperative planning is important to identify associated anomalies necessary for the safe conduct of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, hepatectomy, split liver transplantation, or living donor liver hepatectomy in transplantation. If a left-sided gallbladder is found on enhanced CT imaging, further study such as angiography, CT angiography or MRI studies can provide more detailed vascular and even biliary anomalies for preoperative planning. Although left-sided gallbladders with segment IV atrophy have been reported[5,6,8], we propose that segment IV is not atrophic but embedded in the hypoplastic right lobe. However, not all cases in our study were defined by CT and angiography.

Left-sided gallbladders with right-sided ligamentum teres are a rare anomaly associated portal vein anomalies, biliary system anomalies, and the absence of segment IV. The associated anomalies are important entities during liver resection, complicated hepatolithiasis, and in liver transplantation. Preoperative diagnosis of left-sided gallbladders with associated anomalies is indispensable to minimize the incidence of operative complications.

Although preoperative diagnosis of left-sided gallbladders is important, there are only a few reported case series of left-sided gallbladders. We assessed the imaging presentation on US, CT and angiography of left-sided gallbladders, which was diagnosed if a right-sided ligamentum teres was present on CT.

This study of nine cases is the largest reported to date with detailed imaging presentation by US, CT and angiography. The etiology of left-sided gallbladders was investigated with the imaging presentations of hepatic vein anomalies, hepatic artery anomalies, biliary anomalies and the absence of segment IV of the liver.

Awareness of the special imaging presentations of left-sided gallbladders on US, CT and angiography is important to make an accurate diagnosis. Identification of the associated anomalies will prevent dangerous maneuvers in hepatectomy, split liver transplantation, or living donor liver hepatectomy in transplantation.

A left-sided gallbladder is defined as a gallbladder located to the left side of the ligamentum teres. The anomalies associated with left-sided gallbladders, including portal vein anomalies, biliary system anomalies, and segment IV atrophy, were reported. Segment IV is one of three hepatic segments that constitute the left lobe of the liver. It lies between the falciform ligament and the vertical plane of the right hepatic vein, and is demarcated on the diaphragmatic surface of the liver by a line extrapolated from the fossa for the gallbladder to the inferior vena cava; the medial segment is supplied by medial branches of the umbilical part of the left branch of the portal vein.

The authors assessed the importance of preoperative diagnosis and presentation of left-sided gallbladders using US, CT and angiography. They concluded that left-sided gallbladders are an important clinical entity in hepatectomy, because of their associated portal venous and biliary anomalies. It should be considered in US, CT and angiography images that demonstrate no definite segment IV, absence of umbilical portion of the portal vein in the left lobe, and club-shaped right anterior portal vein.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Hochstetter F. Anomalien der Pfortader und der Nabelvene in Verbindung mit Defect oder Linkslage der Gallenblase. Arch Anat Entwick. 1886;369-384. |

| 2. | Chuang VP. The aberrant gallbladder: angiographic and radioisotopic considerations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;127:417-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Meilstrup JW, Hopper KD, Thieme GA. Imaging of gallbladder variants. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:1205-1208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fujita N, Shirai Y, Kawaguchi H, Tsukada K, Hatakeyama H. Left-sided gallbladder on the basis of a right-sided round ligament. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1482-1484. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Nagai M, Kubota K, Kawasaki S, Takayama T, BandaiY M. Are left-sided gallbladders really located on the left side? Ann Surg. 1997;225:274-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Idu M, Jakimowicz J, Iuppa A, Cuschieri A. Hepatobiliary anatomy in patients with transposition of the gallbladder: implications for safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1442-1443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Maetani Y, Itoh K, Kojima N, Tabuchi T, Shibata T, Asonuma K, Tanaka K, Konishi J. Portal vein anomaly associated with deviation of the ligamentum teres to the right and malposition of the gallbladder. Radiology. 1998;207:723-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Asonuma K, Shapiro AM, Inomata Y, Uryuhara K, Uemoto S, Tanaka K. Living related liver transplantation from donors with the left-sided gallbladder/portal vein anomaly. Transplantation. 1999;68:1610-1612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Baba Y, Hokotate H, Nishi H, Inoue H, Nakajo M. Intrahepatic portal venous variations: demonstration by helical CT during arterial portography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:802-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ikoma A, Tanaka K, Hamada N, Honbo K, Yamauchi T, Ishizaki N, Taira A, Mukai M. Left-sided gallbladder with accessory liver accompanied by intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;93:434-436. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kaneoka Y, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, Harada T. Hepatectomy for cholangiocarcinoma complicated with right umbilical portion: anomalous configuration of the intrahepatic biliary tree. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2000;7:321-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hwang S, Lee SG, Park KM, Lee YJ, Ahn CS, Kim KH, Moon DB, Ha TY, Cho SH, Oh KB. Hepatectomy of living donors with a left-sided gallbladder and multiple combined anomalies for adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:141-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Matsumoto H. A newer concept of segmentation of the liver. Jpn J Med Ultrasonics. 1986;48:551-552. |

| 14. | Kuwayama M, Takeuuchi K, Tsuruoka N, Inoue Y, Shiroyama M, Tsuru C, Nakanishi S. Ultrasonic evaluation of the different branching patterns of the portal vein in the hepatic hilum with special reference to anomalous branching patterns. Jpn J Med Ultrasonics. 1989;16:346-353. |

| 15. | Gross R. Congenital anomalies of the gallbladder. A review of 148 cases, with report of a double gallbladder. Arch Surg. 1936;32:131-162. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ozeki Y, Onitsuka A, Hayashi M, Sasaki E. Left-sided gallbladder: report of a case and study of 26 cases in Japan. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1987;88:1644-1650. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kubo S, Lee S, Yamamoto T, Edagawa A, Kinoshita H. Left-sided gallbladder associated with anomalous branching of the portal vein detected by sonography. Osaka City Med J. 2000;46:95-98. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ozeki Y, Onituka A, Hino A. Anomalous branching of intrahepatic portal vein associated with anomalous position of round ligament. Kanzou. 1989;30:372-378. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yang DM, Kim H, Kang JH, Park CH, Chang SK, Jin W, Kim HS. Anomaly of the portal vein with total ramification of the intrahepatic portal branches from the right umbilical portion: CT features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005;29:461-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gruttadauria S, Foglieni CS, Doria C, Luca A, Lauro A, Marino IR. The hepatic artery in liver transplantation and surgery: vascular anomalies in 701 cases. Clin Transplant. 2001;15:359-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cheng YF, Huang TL, Chen CL, Sheen-Chen SM, Lui CC, Chen TY, Lee TY. Anatomic dissociation between the intrahepatic bile duct and portal vein: risk factors for left hepatectomy. World J Surg. 1997;21:297-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Newcombe JF, Henley FA. Left-Sided Gallbladder. A Review of the Literature and a Report of a Case Associated with Hepatic Duct Carcinoma. Arch Surg. 1964;88:494-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nakanishi S, Shiraki K, Yamamoto K, Koyama M, Nakano T. An anomaly in persistent right umbilical vein of portal vein diagnosed by ultrasonography. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1179-1181. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Cheng YF, Chen TY, Ko SF, Huang CC, Huang TL, Weng HH, Lee TY, Sheen-Chen SM. Treatment of postoperative residual hepatolithiasis after progressive stenting of associated bile duct strictures through the T-tube tract. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1995;18:77-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Deshpande RR, Heaton ND, Rela M. Surgical anatomy of segmental liver transplantation. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1078-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cheng YF, Huang TL, Lee TY, Chen TY, Chen CL. Variation of the intrahepatic portal vein; angiographic demonstration and application in living-related hepatic transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1996;28:1667-1668. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Rocca JP, Rodriguez-Davalos MI, Burke-Davis M, Marvin MR, Sheiner PA, Facciuto ME. Living-donor hepatectomy in right-sided round-ligament liver: importance of mapping the anatomy to the left medial segment. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:454-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cheng YF, Lee TY, Sheen-Chen SM, Huang TL, Chen TY. Treatment of complicated hepatolithiasis with intrahepatic biliary stricture by ductal dilatation and stenting: long-term results. World J Surg. 2000;24:712-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Puente SG, Bannura GC. Radiological anatomy of the biliary tract: variations and congenital abnormalities. World J Surg. 1983;7:271-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |