Published online Dec 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i46.6281

Revised: September 6, 2007

Accepted: October 15, 2007

Published online: December 14, 2007

We report here how a heterotopic penetrating peptic ulcer progressed to cause small bowel obstruction in a patient with multiple previous negative investigations. The clinical presentation, radiographic features and pathological findings of this case are described, along with the salient lessons learnt. The added value of wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) in such circumstances is debated.

- Citation: Hurley H, Cahill RA, Ryan P, Morcos AI, Redmond HP, Kiely HM. Penetrating ectopic peptic ulcer in the absence of Meckel’s diverticulum ultimately presenting as small bowel obstruction. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(46): 6281-6283

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i46/6281.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i46.6281

Heterotopic gastric mucosa resulting in peptic ulceration in the absence of a Meckel’s diverticulum is a most unusual cause of small bowel symptomatology[1]. Although wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) enables painless visualization of the small bowel in a non-invasive manner, its added value in cases not presenting with occult gastrointestinal blood loss is unclear. In this report, we consider what extra value this technology added to the care of a patient who had had multiple negative standard investigations, and ultimately required a laparotomy and ileal resection for definitive management.

A 77-year-old man presented to the Accident and Emergency Department of our hospital with subacute small bowel obstruction, having complained for many years of intermittent severe central abdominal discomfort associated with episodic distension and constipation. Prior to this admission, these symptoms had been extensively investigated by means of plain radiology, computerized tomography (CT) and barium contrast studies, as well as by both upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy, but to no avail. Furthermore, laparotomy at the time of one such presentation had been performed but without therapeutic benefit, as no evidence of overt intestinal pathology or abnormality was found (in particular, there was no evidence of Meckel’s diverticulum). On this latest presentation, the clinical examination was consistent with subacute small bowel obstruction (distended but soft, moderately tender abdomen, with hyperactive bowel sounds and signs of extracellular fluid depletion). Plain abdominal radiography revealed the presence of dilated loops of the small bowel, while subsequent abdominal CT confirmed this finding but did not identify a transition point or any mass lesion. Initial treatment involved correction of fluid and electrolyte abnormalities and nasogastric aspiration for symptomatic relief. Mindful of his past history, when the symptoms persisted for more than 48 h, small bowel barium follow-through was performed. This also failed to define any specific pathology, although the barium failed to progress beyond the proximal jejunum.

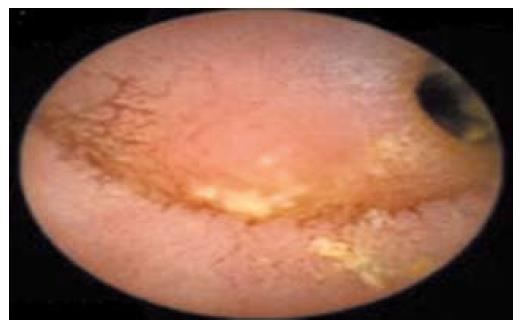

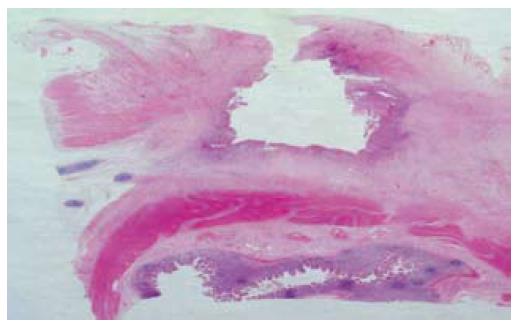

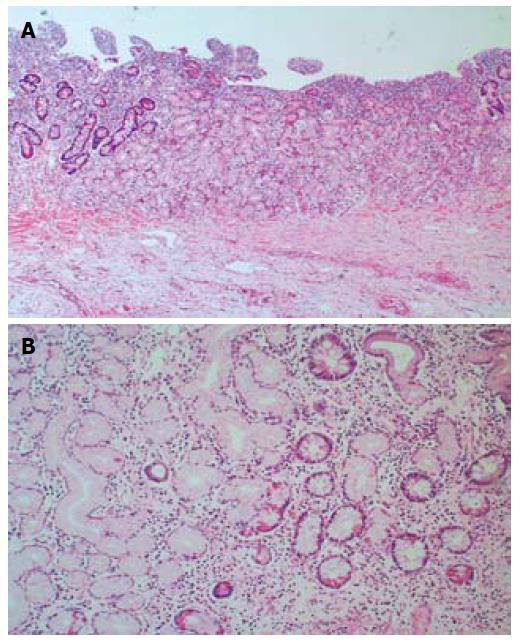

As the patients symptoms had somewhat relented by this stage and he resumed passing flatus again, he was therefore permitted some oral diet which he tolerated despite some intermittent, colicky pain. Although a second laparotomy was advocated because of the on-going persistence of low-grade symptoms, the patient was reluctant, on empiric reasons alone, to consider this given the lack of impact from his previous operation. WCE was therefore performed on a somewhat speculative basis. This test again demonstrated a prolonged transit time through the small bowel (the capsule had not progressed through the jejunum after 7 h), but the last frame of the study showed a raised mucosal jejunal lesion adjacent to an area of severe luminal stenosis (Figure 1). Along with the non-resolving symptoms, identification of this suspicious mucosal lesion, compounded by capsule retention, strengthened the case for exploratory laparotomy. The patient consented. At operation, two adjacent loops of densely adherent jejenum were obvious among other areas of peritoneal adhesions. There were also features of chronic dilatation proximal to an area of luminal stricturing within one of these loops of bowel. Careful adhesiolysis permitted resection of a segment of chronically obstructed aperistaltic small bowel, as well as allowing for the retrieval of the capsule. A primary hand-sewn end-to-end jejunojejunal anastomosis was performed. Opening of the specimen subsequently revealed an underlying oval mucosal ulcer with punched out edges extending through the wall, which caused fibrosis and adhesion to the adjacent loops of bowel (Figure 2). Histological examination of the resected specimen identified foci of heterotopic gastric mucosa adjacent to this deep penetrating chronic peptic ulcer (Figure 3). The patient thereafter made an uncomplicated recovery and remains symptom-free 6 mo later.

Heterotopic gastric mucosa in the small bowel, other than in Meckel’s diverticulum or other congenitally anomalous bowel, is rare[2]. Such lesions usually cause small bowel obstruction, either secondary to a mechanical lesion in the lumen[1], or intermittently due to intussusception of the ectopic mass[2-5]. Acute presentation with a perforating ulcer is rarely seen; indeed, there have been only five cases reported in the literature[1-4], with a further five being reported as causing hemorrhage due to ulcer penetration[1]. In our patient, an ulcerating ectopic mucosal lesion presented unusually as small bowel obstruction secondary to an extensive fibrotic reaction. In this case, there was no macroscopic evidence of diverticulum, luminal duplication, or congenital anomaly. Due to the dense adhesional mass and desmoplastic reaction, it was not possible to identify whether the ulcer was on the mesenteric or anti-mesenteric border of the small bowel, but the penetrating jejunal ulcer was clearly present at the site of the transition point between the dilated and normal caliber small bowel. Microscopic examination of the lesion yielded evidence of ectopic gastric mucosa adjacent to the deep penetrating ulcer, associated with features of chronic inflammation and fibrosis. A diagnosis of chronic peptic ulcer, secondary to heterotopic gastric mucosa with reactive adjacent fibrosis and adhesions was therefore concluded.

The development of WCE technology has changed investigative endoscopy of the small bowel into a much less invasive and more complete examination. A now-proven reliable tool for verifying the state of the small bowel[2], it has been particularly successful in finding the cause of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding[3] and chronic diarrhea, and in evaluating the extent of Crohn’s disease. It is not generally used in cases of small bowel obstruction, due to the risk of capsule retention that should precipitate surgical intervention. In patients with undiagnosed abdominal pain, the yield from the use of WCE appears low, whereas in this case, it proved useful in securing a pathological diagnosis and furthering management[4], as there was an understandable reluctance by the patient to proceed to a second laparotomy without a strong positive indication and likelihood of therapeutic benefit. This case therefore adds some weight to the argument that judicicious use of WCE in small bowel obstruction may identify the site of obstruction and guide surgical intervention[5,6]. In particular, this could be of great significance for a surgeon attempting to localize otherwise non-apparent pathology intraoperatively. In this case, WCE was considered only in the setting of multiple negative investigations and a high probability of operative intervention, given the high risk of capsule retention.

While WCE added little objective evidence to the findings at the latter operation, it is intriguing to speculate how this test may have guided intervention at the time of first surgery. Although small bowel ulcers, ileal tuberculosis and even worm infestation have previously been demonstrated by WCE, most small bowel pathology found to date has been Crohn’s disease or NSAID-related lesions of the distal small bowel[5]. There is only one previous case in the literature of heterotopic gastric mucosa of the small bowel identified by capsule endoscopy[6]. Although the captured images in this case did not diagnose the specific lesion, they did suggest a mucosal anomaly and secondary stenosis, which was subsequently histologically identified as ulcerating heterotopic gastric mucosa. If knowledge of such an abnormality had been available prior to the first operation, perhaps that intervention could have been tailored with therapeutic benefit.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Lodge JP, Brennan TG, Chapman AH. Heterotopic gastric mucosa presenting as small-bowel obstruction. Br J Radiol. 1987;60:710-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sturniolo GC, Di Leo V, Vettorato MG, De Boni M, Lamboglia F, De Bona M, Bellumat A, Martines D, D'Inca R. Small bowel exploration by wireless capsule endoscopy: results from 314 procedures. Am J Med. 2006;119:341-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, De Franchis R. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bardan E, Nadler M, Chowers Y, Fidder H, Bar-Meir S. Capsule endoscopy for the evaluation of patients with chronic abdominal pain. Endoscopy. 2003;35:688-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fireman Z, Mahajna E, Broide E, Shapiro M, Fich L, Sternberg A, Kopelman Y, Scapa E. Diagnosing small bowel Crohn's disease with wireless capsule endoscopy. Gut. 2003;52:390-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bailey AA, Debinski HS, Appleyard MN, Remedios ML, Hooper JE, Walsh AJ, Selby WS. Diagnosis and outcome of small bowel tumors found by capsule endoscopy: a three-center Australian experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2237-2243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |