INTRODUCTION

Since the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the last two decades, minimally invasive surgery has evolved through advances in videoscopic technology, instrumentation, and surgical techniques[1-14]. Currently, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is widely accepted as the gold standard in the treatment of cholelithiasis[15-18]. This new technique was initially associated with a significant increase in morbidity, and in particular, in iatrogenic biliary injury and arterial hemorrhage[19-30], perhaps due to a lack of knowledge of the laparoscopic anatomy of the gallbladder pedicle. Therefore, the laparoscopic surgeon has to deal with the new anatomical views and must be aware of the possible arterial and biliary variants.

A good knowledge of Calot's triangle is important for conventional and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Calot's triangle is an important imaginary referent area for biliary surgery. In 1981, Rocko drew attention to possible variations in the region of Calot's triangle bordered by the cystic duct, common hepatic duct, and lower edge of the liver[31]. In 1992, Hugh suggested Calot's triangle should be renamed the hepatobiliary triangle, with the small cystic artery branches supplying the cystic duct being called Calot's arteries[32].

Cystic artery bleeding is a troublesome complication during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which increases the rate of conversion to open surgery. If surgery is performed incorrectly, injury to the extrahepatic bile duct or intra-abdominal organs is inevitable. The reported incidence of conversion to open surgery because of blood vessel injuries is approximately 0%-1.9% during laparoscopic cholecystectomy[33], and its mortality is about 0.02%[34]. Safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy demands a good knowledge of the anatomy of the cystic artery and its variations.

The cystic artery has many possible origins, with the right hepatic artery being the most common[35]. The anatomy with respect to the cystic artery between laparoscopic cholecystectomy and open cholecystectomy is different. We investigated the appearance of the cystic artery during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and proposed a new classification system for the cystic artery during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, according to our practical experience.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between June 2005 and May 2006, we undertook a retrospective evaluation of 600 non-emergency patients, 232 men and 368 women, who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy for different gallbladder diseases, including 530 with cholecystitis and gallstones, and 70 with gallbladder polyps. All of the patients were examined with ultrasound before surgery.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was carried out under general anesthesia using the four ports technique. The information of Calot's triangle and distribution of cystic artery on endoscopic visualization was recorded respectively. A laparoscope (Stryker, USA) at 30˚ tilt angle was used. The anatomical structures were viewed on a three-dimensional video monitor.

RESULTS

Based on our laparoscopic observations, we classified cystic artery anatomy into three groups.

Group I

GroupIrepresents the Calot's triangle type, in which the cystic artery passes through Calot's triangle. The anatomic location of the cystic artery can be found ahead or behind of the cystic duct, and in hepatoduodenal ligament, under laparoscopic observation. This is the most common type and has been reported in about 80%-96% of cases in previous studies[35,36]. We observed this type in 513 of the 600 patients (85.5%). Group I is further subdivided into two subtypes, as follows.

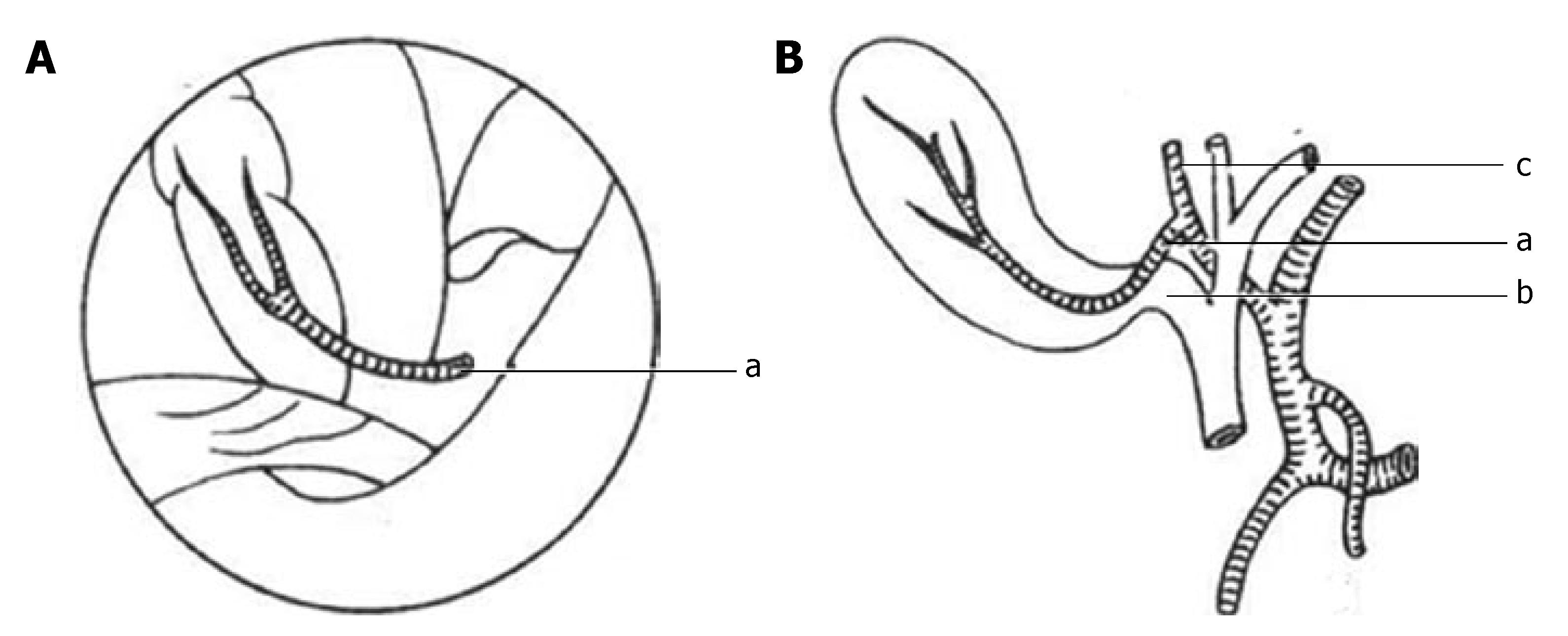

Classical single cystic artery: The cystic artery originates from the right hepatic artery within Calot's triangle. When approaching the gallbladder, the artery is divided into deep and superficial branches at the neck of the gallbladder. The superficial branch proceeds along the left side of the gallbladder. The deep branch runs through the connective tissues between the gallbladder and liver parenchyma. The deep branch gives rise to tiny branches to supply the gallbladder, which anastomose with the superficial branches. This type of cystic artery is laterally positioned from the cystic duct within Calot's triangle during open cholecystectomy, whereas during laparoscopic cholecystectomy it is just behind and slightly deeper than the cystic duct. According to the literature, this type is found in 70%-80% of cases[32,35]. In our study it was recorded in 440 of 600 patients (73.3%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Classical single cystic artery.

A: Laparoscopic visualization; B: Conventional visualization. a: Cystic artery; b: Cystic duct; c: Right hepatic artery.

Suzuki et al has reported a special example of this type. A single cystic artery originates from the right hepatic artery and then hooks around the cystic duct from behind and reappears at the peritoneal surface near the neck of the gallbladder. They named this the cystic artery syndrome[37]. We did not find any examples of this type in our study.

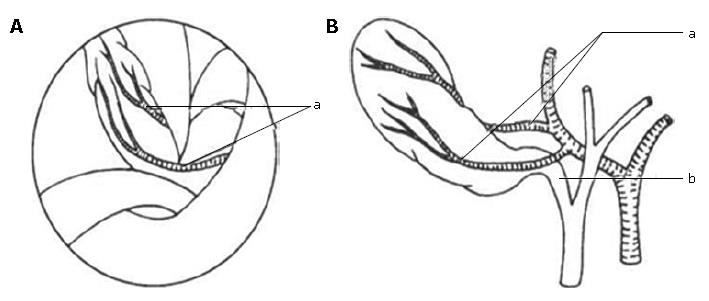

Double cystic artery: The cystic artery also originates from the right hepatic artery, while it divides into the anterior and posterior branches at their cystic artery origin. Congenital absence of the deep branch signifies the existence of another cystic artery, which is occasionally detected by subsequent bleeding control. The posterior cystic artery is very delicate in some cases and is often cut by electrocoagulation during dissection. A double cystic artery has previously been found in 15%-25% of patients[32]. During our laparoscopic cholecystectomy we recorded 73 patients (12.2%) with double cystic artery (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Double cystic artery.

A: Laparoscopic visualization; B: Conventional visualization. a: Cystic artery; b: Cystic duct.

Group II

Cystic artery approaches the gallbladder outside Calot's triangle and cannot be observed within the triangle by laparoscopy during dissection. We found 78 patients (13%) in group II during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This group includes the following four subgroups.

Cystic artery originating from gastroduodenal artery: This type of cystic artery is also called low-lying cystic artery, which does not pass through Calot's triangle but approaches the gallbladder beyond it. In conventional open cholecystectomy it is seen as inferior to the cystic duct, while it usually localizes superficially and anterior to the cystic duct from a laparoscopic viewpoint. Its terminal segment as it approaches the gallbladder is important for laparoscopic surgeons. Because it not only must be manipulated at first, but it is also susceptible to injury and hemorrhage during dissection of the peritoneal folds that connect the hepatoduodenal ligament to Hartman's pouch of the gallbladder or to the cystic duct. This anatomic variation was found in 45 patients (7.5%) in our study (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Cystic artery originating from gastroduodenal artery.

A: Laparoscopic visualization; B: Conventional visualization. a: Cystic artery; b: Cystic duct; c: Gastro-duodenal artery.

Cystic artery originating from the variant right hepatic artery: Anatomic variation of the right hepatic artery usually originates from the superior mesenteric artery or aorta[32,38]. It enters Calot's triangle behind the portal vein, and runs parallel to the cystic duct on its passage through the triangle. It can be completely covered by the cystic duct of the gallbladder[32]. We found a very interesting type of right hepatic artery variant. This artery has a long course, approaching the gallbladder deep at its neck, and then passing between the gallbladder and liver parenchyma, extending along the deep right side of the gallbladder, and finally entering the liver parenchyma near the right-lateral side of the gallbladder fundus. It yields multiple small branches to supply the gallbladder at its body, and it is often completely covered by the gallbladder. We should be cautious of this right hepatic artery variation. From the laparoscopic viewpoint it looks like a single large artery. This anatomic variation was found in 18 patients (3%) in our study (Figure 4). Variant right hepatic artery has been shown to have a prevalence of approximate 4%-15%[37,39].

Figure 4 Cystic artery originating from variant right hepatic artery.

A: Laparoscopic visualization; B: Conventional visualization; C: Video in operation. a: Cystic artery; b:Cystic duct; c: Variant right hepatic artery; GF: Fundus of gallbladder; CD: Cystic duct; GN: Neck of gallbladder; LV: Liver; VRHA: Variant right hepatic artery.

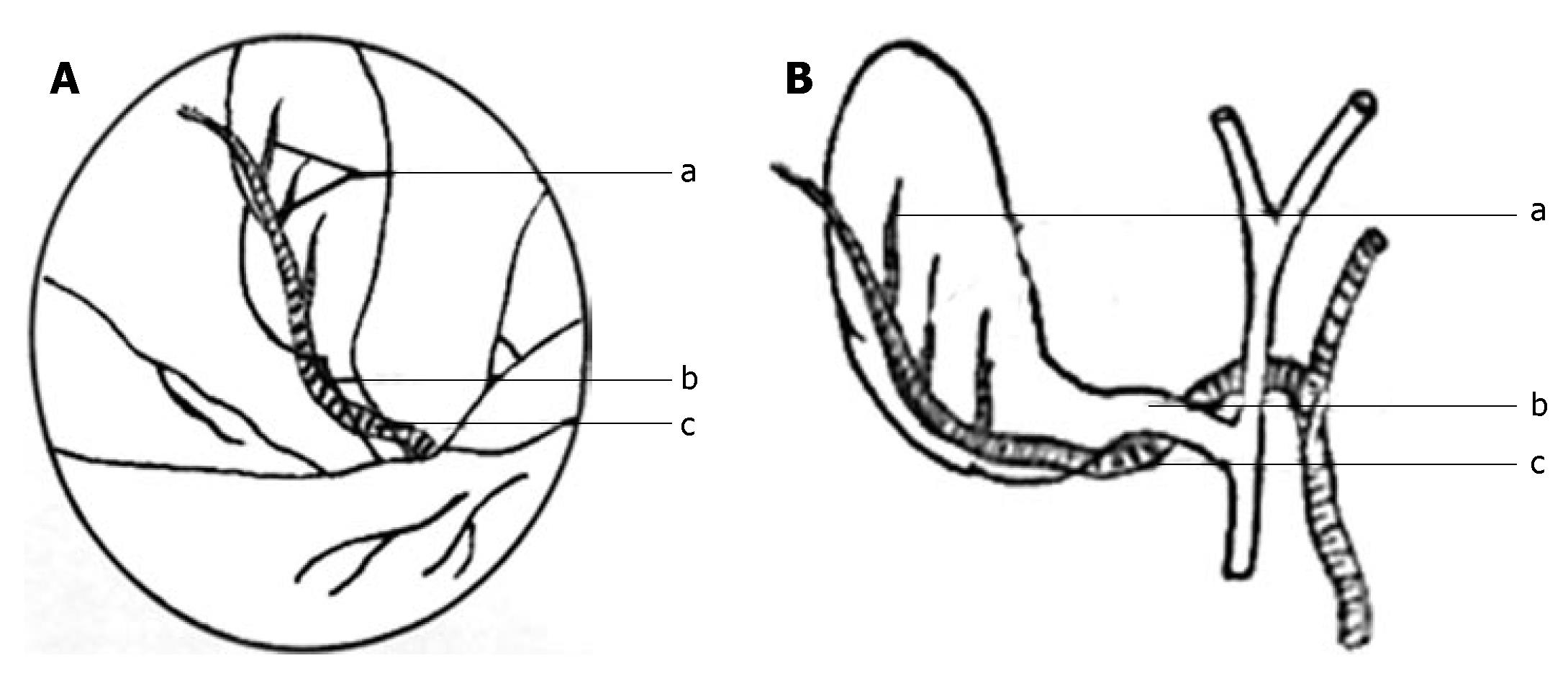

Cystic artery originating directly from the liver parenchyma: This cystic artery pierces the hepatic parenchyma approaching the bladder from the gallbladder bed. It usually situates in the right lateral of the border of gallbladder body and bottom. However, a few are situated in the center of the gallbladder bed or situated left lateral of gallbladder bottom. No other arteries are found within Calot's triangle. This anatomic variation of the cystic artery is not observed until bleeding and is caused by dissection of the gallbladder fundus. It is difficult to explore and requires careful dissection. We found it in 15 patients (2.5%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Cystic artery arising from hepatic parenchyma.

A:Laparoscopic visualization; B:Conventional visualization. a: Cystic artery; b: Cystic duct.

Cystic artery originating from the left hepatic artery:The cystic artery occasionally originates from the left hepatic artery, passes through the liver parenchyma, and reaches the middle of the gallbladder body, at which point it bifurcates into ascending and descending branches. This has a prevalence of 1%[39]. However, we did not find this type of variant cystic artery.

Group III

This group has more than one blood supply. We named it the compound cystic artery type. The cystic arteries exist not only in Calot's triangle, but also outside it. We found that nine patients (1.5%) belonged to this group. Five of these patients (0.8%) had a normal single cystic artery in Calot's triangle, and an artery extending along the cystic duct but posterior to it, and some small arteries that passed immediately from the liver parenchyma to the gallbladder. Three of the nine patients (0.5%) had another cystic artery superficial to the cystic duct in addition to the normal cystic artery. Finally, one patient (0.17%) had multiple cystic arteries, including the double cystic artery in Calot's

triangle, and one of the arteries crossed anterior to the common bile duct, while another was situated on the right side of the border of the gallbladder body and fundus.

DISCUSSION

Anatomic variations in and around Calot's triangle are frequent (biliary tree, cystic artery)[40,41], and we found them in 20%-50% of patients. Therefore, careful blunt dissection of Calot's triangle is necessary for both conventional and laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Since the introduction of laparoscopic gallbladder surgery, surgeons have been very interested in gallbladder vascularization. A great number of papers on this issue have been published[36,42-44], although some vagueness still exists, because of the diversity of data and classification. There have been relatively few reports on the laparoscopic anatomy of the hepatobiliary triangle, especially of the cystic artery.

It is important for every laparoscopic surgeon to be familiar with the anatomic variations in the extrahepatic biliary tree and those of the arterial supply of the gallbladder. The possible anatomic position and variations of the cystic artery are difficult to establish before surgery. They were only identified during disconnection of Calot's triangle and the gallbladder. The laparoscopic anatomy of the cystic artery can be considered as a precondition for performing safe laparoscopic procedures. The variations of cystic artery often make surgeons recognize an error, causing them to abscise incorrectly and, subsequently, leading to a hemorrhage. When hemorrhage cannot be controlled, conversion to open cholecystectomy is inevitable.

The position of the cystic artery appears differently during laparoscopic and conventional cholecystectomy for the following reasons. (1) Under laparoscopy, as the gallbladder fundus is pulled, the liver is moved upward, thereby opening the subhepatic space. (2) By pulling Hartman's pouch downward, the anterior aspect of Calot's triangle is presented. On the contrary, by pulling Hartman's pouch upward, the posterior aspect of Calot's triangle is clearly exposed. (3) Better transparency and visualization under laparoscopy facilitates recognition of cystic artery variation by the surgeon.

Previous studies have contained fewer reports on the laparoscopic classification of the cystic artery. Some have divided the cystic artery into low-lying cystic artery and cystic artery originating from variant right hepatic artery. Balija classified cystic artery variations into two groups. GroupIcomprises five variations of the cystic artery within the hepatobiliary triangle: (a) normal position; (b) frontal cystic artery; (c) backside; (d) multiple; and (e) short cystic artery that arises from an aberrant right hepatic artery. Group II consists of variations of the cystic artery that approaches the gallbladder beyond the hepatobiliary triangle: (a) low-lying; (b) transhepatic; and (c) recurrent cystic artery[36]. Ignjatovic has divided the cystic artery into three types in minimally invasive surgical procedures: type 1 shows normal anatomy; type 2 more than one artery in Calot's triangle; and type 3 no artery in Calot's triangle[45]. However, none of the above classifications satisfies the practical needs of laparoscopic surgery. Based on our experience, the anatomic variations of the cystic artery can be classified into three groups. GroupIshowed the cystic artery passing within Calot's triangle. It included two types: (1) single cystic artery, found in 440 patients (73.3%); and (2) double cystic artery, observed in 73 patients (12.2%). Group II showed the cystic artery situated outside Calot's triangle. This group included four variations: (1) cystic artery originating from the gastroduodenal artery, found in 45 patients (7.5%); (2) cystic artery originating from the variant right hepatic artery, found in 18 patients (3%); (3) cystic artery directly arising from the liver parenchyma, observed in 15 patients (2.5%); and (4) cystic artery originating from the left hepatic artery. Group III had a compound appearance, with the variant cystic artery situated not only within Calot's triangle, but also outside it. This classification of cystic artery can help surgeons understand the cystic artery more thoroughly, and may be more practical to use in real operations.

Variations in the cystic artery are miscellaneous, and we must be cautious during the performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Our laparoscopic classification of the cystic artery is very useful for dissection of Calot's triangle, reduces uncontrollable cystic artery hemorrhage, and may be advantageous for avoiding extrahepatic bile duct injury.

COMMENTS

Background

Uncontrolled bleeding from the cystic artery and its branches is a serious problem that may increase the risk of intraoperative injury to vital vascular and biliary structures. Anatomic variations of the cystic artery are frequent and can differ in origin, position and number. We investigated 600 cases treated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy and analyzed the anatomic structure of the cystic arteries under laparoscopic observation. The cystic artery variations were classified into three groups: (1) Calot's triangle, (2) outside Calot's triangle, and (3) compound type. These will be helpful to laparoscopic surgeons.

Research frontiers

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is widely accepted as the gold standard in the treatment of gallstone disease. However, the incidence of bile duct injury caused by this procedure is more than that caused by conventional cholecystectomy. The main areas of research in laparoscopic cholecystectomy are as follows: (1) biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy; (2) anatomic characteristics of the cystic artery; (3) intraoperative bleeding during laparoscopic cholecystectomy; (4) cholecystectomy techniques.

Innovations and breakthroughs

There are few reports concerning classification of the cystic artery during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Some authors have classified it into two groups: GroupIcomprises variations of the cystic artery within the hepatobiliary triangle; and Group II comprises variations of the cystic artery that approach the gallbladder beyond the hepatobiliary triangle. Other authors have divided cystic artery variations into three types: type 1, normal anatomy; type 2, more than one artery in Calot's triangle; and type 3, no artery in Calot's triangle. We present a new classification of cystic artery variations based on three groups. Group I shows the cystic artery passing within the Calot's triangle. This includes two types: (1) single cystic artery, and (2) double cystic artery. Group II shows the cystic artery situated outside Calot's triangle. This group includes four variations: (1) cystic artery originating from the gastroduodenal artery; (2) cystic artery originating from the variant right hepatic artery; (3) cystic artery arising directly from the liver parenchyma; (4) cystic artery originating from the left hepatic artery. Group III shows the cystic artery is compound in nature; the variant cystic artery was situated not only within Calot's triangle, but also outside it. Furthermore, we found a new variant right hepatic artery (Figure 4), which has not been reported before.

Peer review

The authors introduce a new classification of cystic artery variations during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Their system is different from those reported previously. The new system divides the anatomic variations of the cystic artery into three groups according to the position of the cystic artery relative to Calot's triangle, as seen by laparoscopy. The classification system should be useful to laparoscopic surgeons, and help reduce incidences of bile duct injury and intraoperative bleeding during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.