Published online Nov 7, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i41.5527

Revised: August 17, 2007

Accepted: September 4, 2007

Published online: November 7, 2007

Mirizzi syndrome is a rare complication of gallstone disease, and results in partial obstruction of the common bile duct or a cholecystobiliary fistula. Moreover, congenital anatomical variants of the cystic duct are common, occurring in 18%-23% of cases, but Mirizzi syndrome underlying an anomalous cystic duct is an important clinical consideration. Here, we present an unusual case of typeIMirizzi syndrome with an uncommon anomalous cystic duct, namely, a low lateral insertion of the cystic duct with a common sheath of cystic duct and common bile duct.

- Citation: Jung CW, Min BW, Song TJ, Son GS, Lee HS, Kim SJ, Um JW. Mirizzi syndrome in an anomalous cystic duct: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(41): 5527-5529

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i41/5527.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i41.5527

Mirizzi described a functional hepatic syndrome in 1948, which consists of obstruction of the common hepatic duct secondary to compression by an impacted gallstone in the cystic duct or in the infundibula of the gallbladder (GB) associated with an inflammatory response involving the cystic duct and the common bile duct (CBD), surrounding inflammation, recurrent cholangitis, and spasm of the circular muscular sphincter in the hepatic duct[1]. Mirizzi syndrome (MS) indicates a narrowing of the common bile duct by a gallstone impacted in the cystic duct or a cholecystobiliary fistula. Many cases have so far been reported, and various operations have been suggested depending on the types of MS. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become the standard operation for gallstones, and many authors have adopted this operation for typeIMS. However, high rates of conversion and bile duct injury indicate that this is not a safe treatment modality for MS, especially when combined with a cystic duct anomaly[2-5]. In this report, we present a case of type IMirizzi syndrome, complicated by a rare anomalous cystic duct, which was operated with an open procedure.

A 34-year-old Korean female presented at our hospital complaining of abdominal pain of 2-d duration. The finding of her physical examination was not remarkable except for tenderness at the right upper abdominal quadrant with a positive Murphy sign. Furthermore, her laboratory findings were not remarkable except for an abnormal liver function: 2.1/1.6 mg/dL bilirubin (total/direct), 126 IU/L alkaline phosphatase, 310 IU/L aspartate aminotransferase, 625 IU/L alanine aminotransferase, and 114 IU/L gamma glutamyl transpeptidase. Ultrasonography (US) revealed multiple gallstones with GB wall thickening and a suspicious 1 cm-sized distal CBD stone. The same findings were also noted on endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was conducted for a closer examination and removal of the CBD stone. However, ERCP showed that the 1 cm-sized gallstone was impacted in an anomalous cystic duct joined with the distal CBD. In addition, a gallstone compressed the CBD at the level of union between the pancreatic and biliary ducts (Figure 1). Mirizzi syndrome with low medial insertion of the cystic duct was preoperatively diagnosed, and endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) tube was placed to decompress the biliary obstruction after endoscopic sphincterotomy.

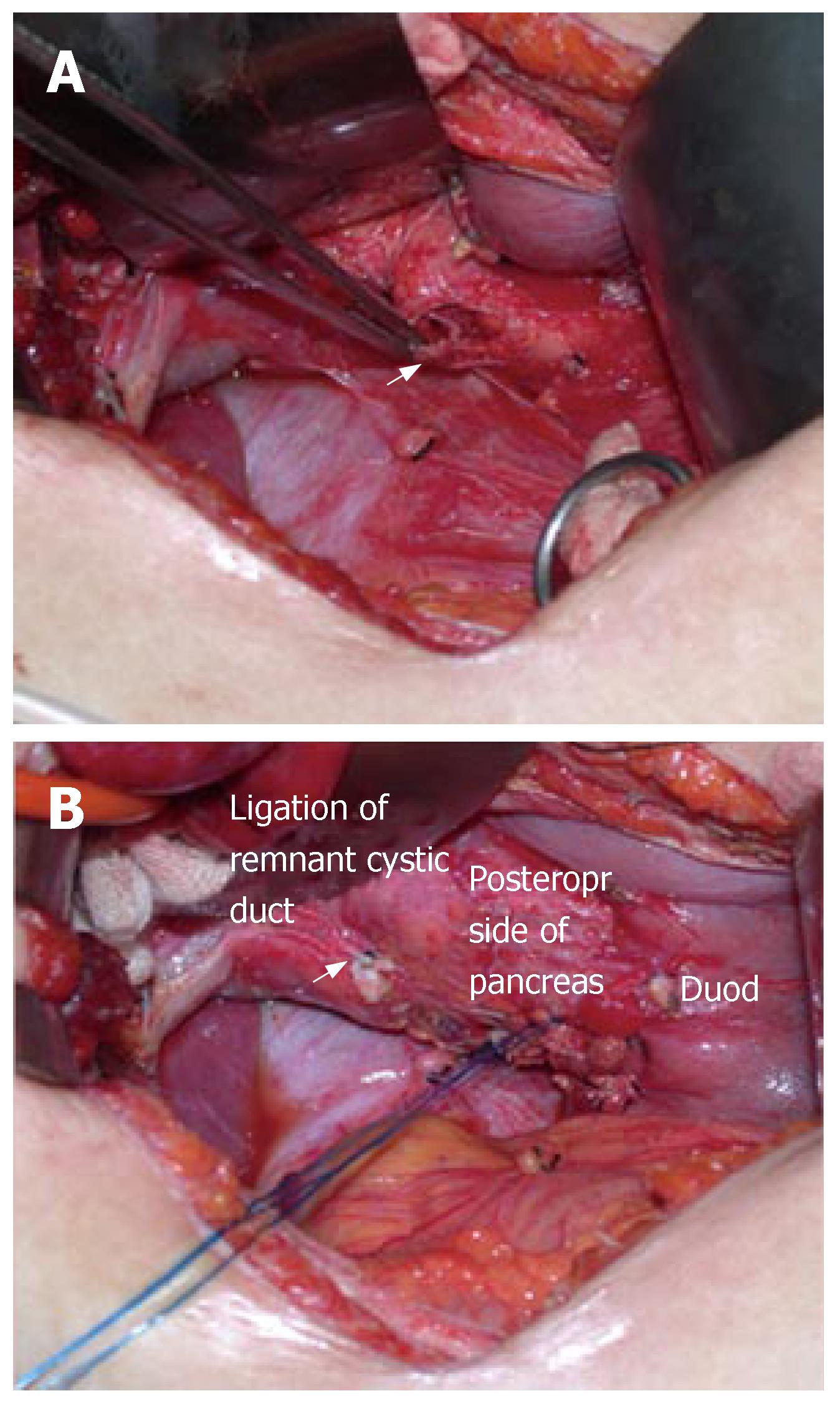

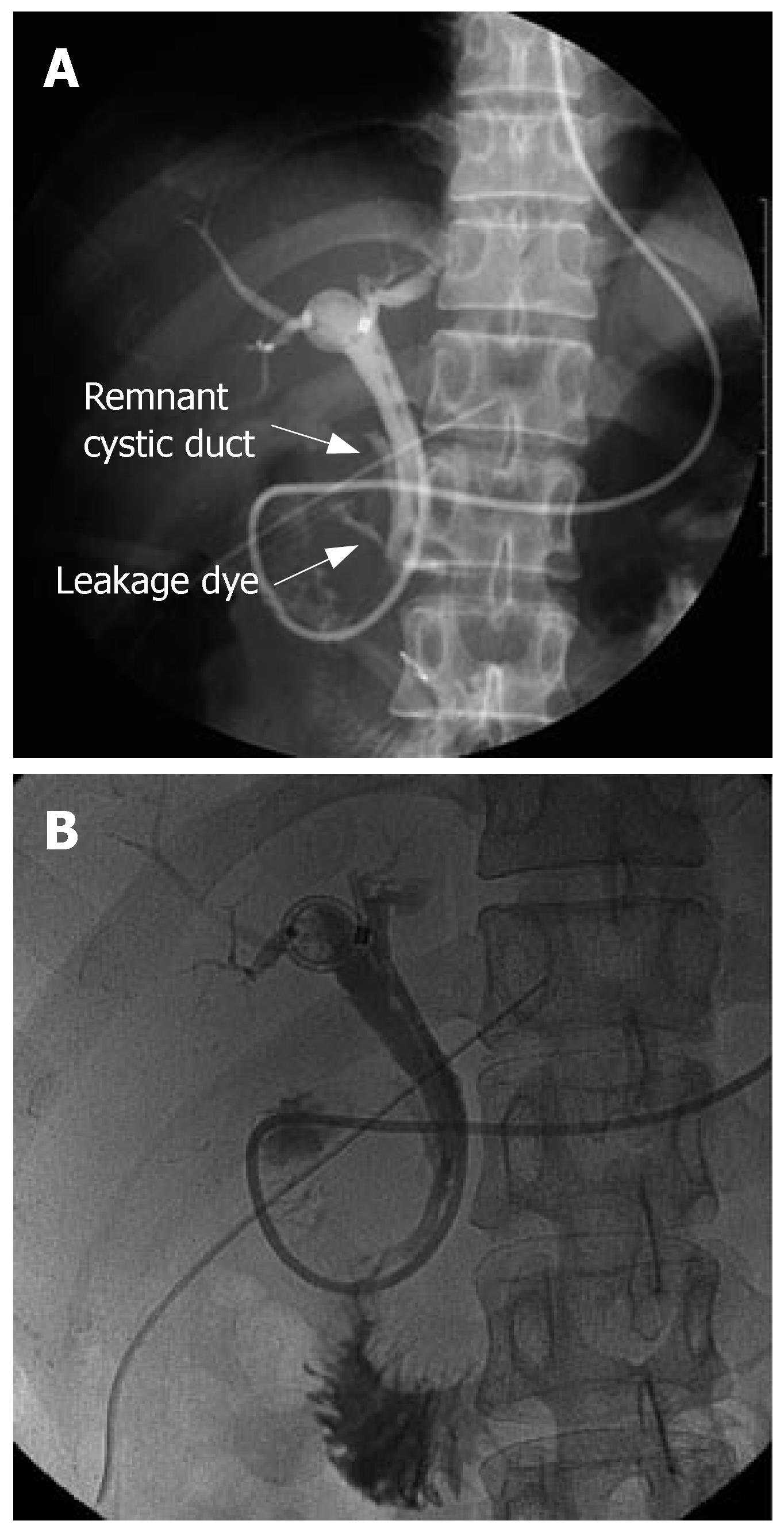

During laparotomy via a right subcostal incision, the GB was found to be shrunken, thickened, and inflamed. The long and dilated cystic duct seen on ERCP was not identified in the operative field, and the GB was strongly attached to the CBD because of chronic inflammation and also possible anomalous union to the CBD (i.e., possibly due to a common sheath cystic duct and CBD). After subtotal cholecystectomy, the remnant of cystic duct was thickened and dilated to about 1.5 cm in diameter. Intraoperative choledochoscopy was performed via the remnant of cystic duct and the impacted cystic duct stone was visualized. However, lithotripsy with choledochoscopy failed at this time. Another attempt was made to remove the cystic duct stone after duodenum mobilization through the remnant of cystic duct using a stone forceps made. Moreover, during this procedure, the pancreas and intrapancreatic portion of the cystic duct were torn, and the impacted cholesterol stone escaped retroperitoneally from the lacerated intrapancreatic cystic duct and pancreas (Figure 2A). After ligation of the stump of remaining cystic duct and primary repair of the torn cystic duct and pancreas (Figure 2B), intraoperative cholangiography via an ENBD tube showed neither leakage nor residual stone. A closed suction type drain was placed in the liver bed and retroduodenal space, and the abdominal wall was then closed. Because the ENBD catheter and endoscopic sphincterotomy were preoperatively performed, they could have played a role in biliary drainage in place of choledochotomy and T-tube insertion. The postoperative course was uneventful, except for minimal drainage from the closed suction drain and minor leakage from the repaired cystic duct, which was visible on the 7th postoperative day on ENBD cholangiography (Figure 3A). After conservative management, no visible leakage was observed from the repaired cystic duct on follow-up ENBD cholangiography on the 21st postoperative day (Figure 3B). After removal of the ENBD catheter, the patient was discharged on the postoperative 23rd d, and has now been doing well for over 3-years.

Congenital anatomical variants of the cystic duct are common, occurring in 18%-23% of cases. Among those cases, the cystic duct inserts into the middle third of the extrahepatic bile duct in 75% of cases and into the distal third in 10% of cases. Five types of cystic duct anomaly have been described: a long cystic duct with low fusion with the CHD, abnormally high fusion between a cystic duct and the CHD, accessory hepatic duct, cystic duct entering the right hepatic duct, and cholecystohepatic duct[6-8]. In particular, low medial insertion of the cystic duct deserves special attention, because this anatomical variant may lead to misdiagnosis by imaging studies, thus adversely affecting therapeutic intervention. In addition, anomalous cystic duct may also be a problem at cholecystectomy[9]. In the presently described case, ERCP demonstrated that the biliary obstruction was caused by a cystic duct gallstone in a low medially inserting cystic duct which joined the distal CBD near the ampulla of Vater, but not by a distal CBD stone as indicated by US and EUS.

Zhou[10] reported that 65 (5.9%) among 1100 cases had an abnormal cystic duct and common bile duct confluence, as determined by ERCP, and he divided cystic duct anomalies into three types, and the very low-sited confluence was found in 9 (13.8%) cases among anomalous cystic ducts. Another study of 50 patients reported a single case (2%) of intrapancreatic confluence[11].

MS is a rare disease entity that accounts for about 0.1%-2.5% of all operations performed for gall bladder stones[12,13]. In 1982, McSherry et al[14] classified MS into two types, based on ERCP findings. TypeIinvolves external compression of the common hepatic duct by a large stone impacted in the cystic duct, or the Hartmann's pouch, without any lesion in the gall bladder or common hepatic duct wall. In type II, a cholecystocholedochal fistula is present, which is caused by a calculus that has eroded partly or completely into the common duct. In 1989, Csendes et al[12] classified MS into four types, and their classification categorized cholecystocholedochal fistula further depending on its extent of destruction. The McSherry classification or the Csendes classification has usually been used by clinicians, because these classifications more usefully guide surgical management.

MS has been highlighted because of its high incidence of iatrogenic biliary injuries and its demand for complex surgical procedures. Preoperative diagnosis of MS is difficult. However, it is important to prevent unexpected intraoperative morbidities, such as bile duct injury.

In the present case, a cystic duct stone was misdiagnosed as a CBD stone by US and EUS. However, in order to evaluate and remove the stone, ERCP was carried out and finally, a cystic duct stone with MS type Icombined with a low lying anomalous cystic duct was diagnosed before surgery. Most MS cases have CBD obstruction symptoms such as jaundice (76.5%), which induce surgeons to attend to CBD problems[2]. However, cases not associated with CBD obstruction symptoms may be diagnosed as GB stone requiring only laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In a series reported by Tan et al[5], bile duct injuries were observed in 4 (16.7%) of 24 operatively treated patients, and all the 4 injuries occurred in patients without a preoperative diagnosis.

Surgical treatment of MS depends on its type. Although laparoscopic cholecystectomy has almost completely replaced open cholecystectomy for the treatment of symptomatic gallstone disease, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is relatively hazardous in patients with MS, because safe dissection of Calot's triangle is difficult due to severe local inflammations and adhesions[4]. Al-Akeely et al[2] reported that 2 of 6 typeIMS patients successfully underwent laparoscopic partial cholecystectomy with an endo-GIA stapler. However, the procedure was converted to an open procedure in the remaining 4 patients. Schafer et al[4] reported that conversion to an open approach was needed in 24 of 34 patients (74%) with typeIMS and in all 5 patients with type II MS.

In the present case, open cholecystectomy was performed for MS combined with a cystic duct anomaly. However, bile duct injury occurred during removal of the impacted cystic duct stone. Thus, we would like to advise that, if MS combined with a cystic duct anomaly is diagnosed before surgery, the operator should not hesitate to perform open surgery and dissect carefully, while considering anatomical deformities associated with chronic inflammation. Moreover, intraoperative cholangiography should be performed to minimize the risk of biliary injury.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Wang HF

| 1. | Mirizzi PL. Sindrome del conducto hepatico. J Int Chirur. 1948;1:219-225. |

| 2. | Al-Akeely MH, Alam MK, Bismar HA, Khalid K, Al-Teimi I, Al-Dossary NF. Mirizzi syndrome: ten years experience from a teaching hospital in Riyadh. World J Surg. 2005;29:1687-1692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Waisberg J, André EA, Franco MI, Abucham-Neto JZ, Wickbold D, Goffi FS. Curative resection plus adjuvant chemotherapy for early stage primary gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a retrospective study with emphasis on prognostic factors and treatment outcome. Arq Gastroenterol. 2006;43:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schäfer M, Schneiter R, Krähenbühl L. Incidence and management of Mirizzi syndrome during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1186-1190; discussion 1191-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tan KY, Chng HC, Chen CY, Tan SM, Poh BK, Hoe MN. Mirizzi syndrome: noteworthy aspects of a retrospective study in one centre. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:833-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Benson EA, Page RE. A practical reappraisal of the anatomy of the extrahepatic bile ducts and arteries. Br J Surg. 1976;63:853-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Puente SG, Bannura GC. Radiological anatomy of the biliary tract: variations and congenital abnormalities. World J Surg. 1983;7:271-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shaw MJ, Dorsher PJ, Vennes JA. Cystic duct anatomy: an endoscopic perspective. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:2102-2106. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ghahremani GG. Postsurgical biliary tract complications. Gastroenterologist. 1997;5:46-57. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Zhou YB. Cystic duct anomalies found by ERCP and their clinical implications. Zhonghua WaiKe ZaZhi. 1990;28:328-330, 380. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ichii H, Takada M, Kashiwagi R, Sakane M, Tabata F, Ku Y, Fujimori T, Kuroda Y. Three-dimensional reconstruction of biliary tract using spiral computed tomography for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2002;26:608-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Csendes A, Díaz JC, Burdiles P, Maluenda F, Nava O. Mirizzi syndrome and cholecystobiliary fistula: a unifying classification. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1139-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shah OJ, Dar MA, Wani MA, Wani NA. Management of Mirizzi syndrome: a new surgical approach. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:423-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | McSherry CK, Ferstenberg H, Virshup M. The Mirizzi syndrome: suggested classification and surgical therapy. Surg Gastroenterol. 1982;1:219-225. |