Published online Oct 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i40.5391

Revised: July 29, 2007

Accepted: August 14, 2007

Published online: October 28, 2007

Small bowel obstructions (SBOs) are primarily caused by adhesions, hernias, neoplasms, or inflammatory strictures. Intraluminal strictures are an uncommon cause of SBO. This report describes our findings in a unique case of sequential, stenotic intraluminal strictures of the small intestine, discusses the differential diagnosis of intraluminal intestinal strictures, and reviews the literature regarding intraluminal pathology.

- Citation: Van Buren II G, Teichgraeber DC, Ghorbani RP, Souchon EA. Sequential stenotic strictures of the small bowel leading to obstruction. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(40): 5391-5393

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i40/5391.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i40.5391

Small bowel obstructions (SBOs) are most commonly caused by adhesions, hernias, neoplasms, or inflammatory strictures[1], with most caused by extraluminal adhesions due to postoperative inflammatory changes[2]. Intraluminal strictures are less common and are primarily caused by congenital defects, inflammation, ischemia, neoplasms, or radiation. We present an unusual case of sequential, stenotic strictures of the small intestine with no clearly defined etiology.

A 43-year-old Hispanic female presented to a surgical service for evaluation of SBO. Four days prior to presentation she developed nausea and mid-epigastric, cramping abdominal pain. She had not been able to tolerate liquids or solids for 2 d.

She had a 22-year history of chronic abdominal pain. An outpatient work-up involving an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan the previous year revealed dilated loops of small intestine, with areas of diffuse thickening of the intestinal wall, but no evidence of obstruction. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed gastritis but no major pathology. Stool cultures sent for Clostridium difficile toxin, ova, and parasites (Iodine and trichrome staining for worms (i.e., Ascaris, Necator, Enterobius, Taenia), amoeba (i.e., Entamoeba), flagellates (i.e., Giardia), cryptosporidium, and others) were negative. Her surgical history included bilateral tubal ligation, open appendectomy, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. She had no personal or family history of trauma, cancer, or inflammatory bowel disease.

The patient was awake and alert with stable vital signs. Her abdomen was soft and mildly distended, with mid-epigastric tenderness upon palpation. She had no peritoneal signs. Her laboratory test values were all within normal limits.

A CT scan of the abdomen revealed a proximal SBO with dilated loops of small intestine and a transition point in the mid jejunum. Distal to the transition point, the intestine was thickened for several centimeters (Figure 1). Distal to the thickened portion, the intestine was normal in appearance. The terminal ileum and colon were normal, and no retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy was present.

On exploratory laparotomy, we found a thickened, dilated proximal small intestine with a clear transition point to the decompressed distal jejunum. The intestine was pink and viable. No extraluminal bands, adhesions or hernias were present. The duodenum and ligament of trietz appeared normal. Distal to the duodenum, the jejunum became thickened and dilated. We found deposits of mesenteric fat on the serosal edge of the intestine every 5-10 cm. Associated with these areas of mesenteric fat were palpable intraluminal stenoses. The rest of the intestine was normal in appearance. There were no intestinal or mesenteric masses. Strong pulses were palpated in all of the mesenteric vessels. We resected the thickened portion of jejunum and mesentery, and performed a jejunojejuno anastomosis.

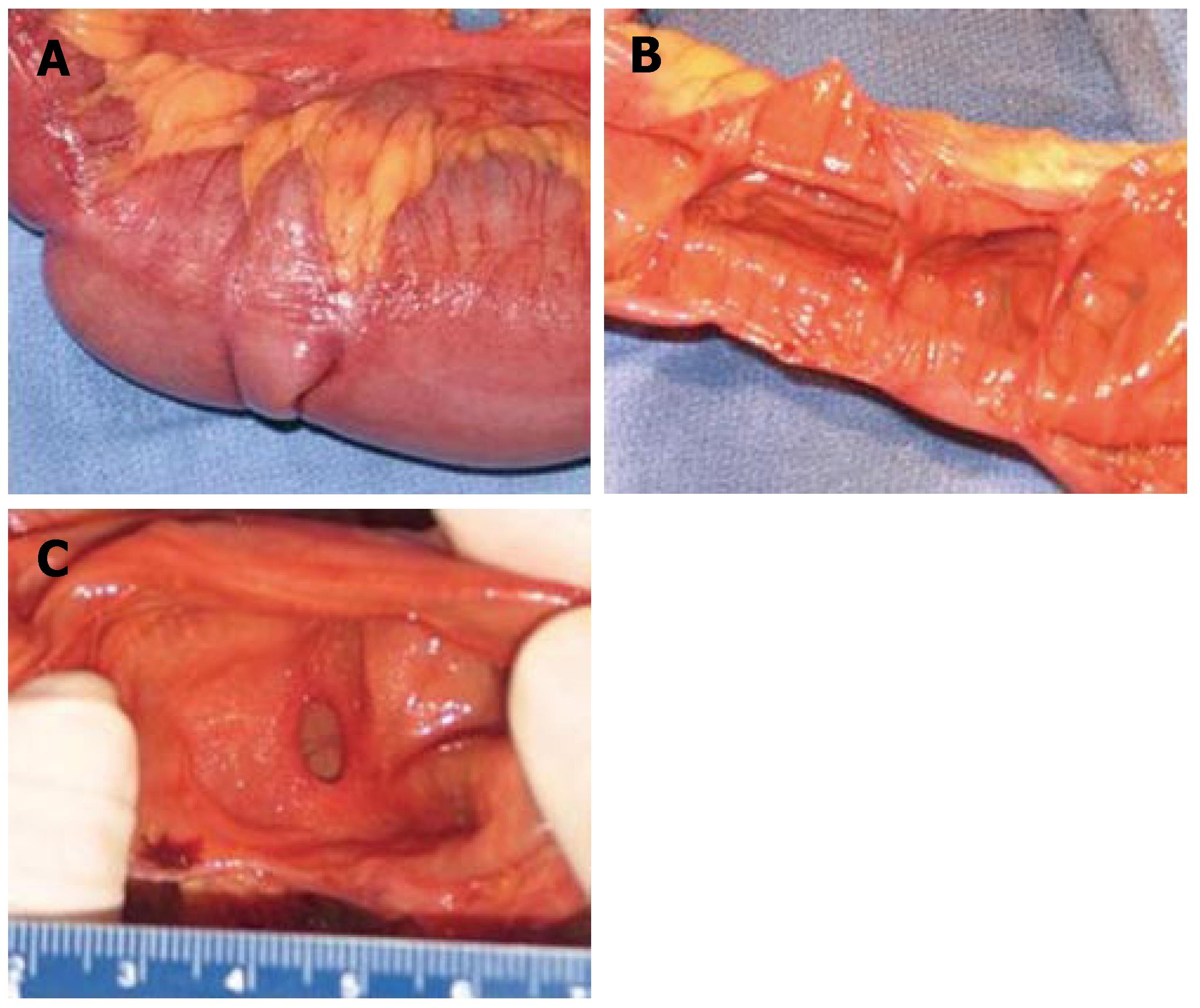

A 76-cm segment of small intestine was resected. On gross examination, fat was seen surrounding the serosal surface of the intestine at irregular intervals at the mesenteric border (Figure 2A). Associated with these deposits of fat were 14 areas of mucosal stricture causing luminal constriction (Figure 2B and C). The lumen between the constrictions was dilated and showed mucosal thinning. In the mesentery, four benign reactive perienteric lymph nodes were present.

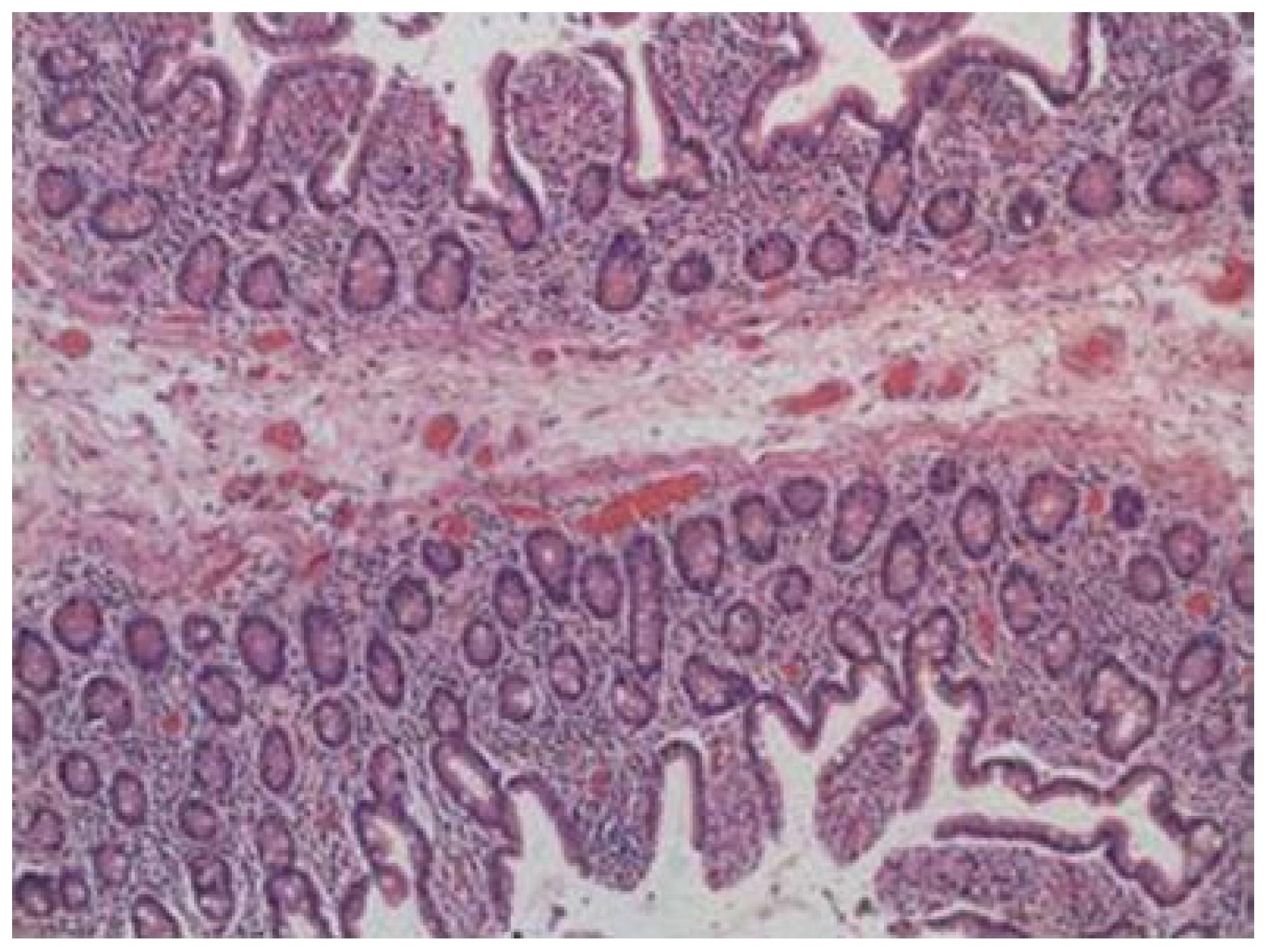

On microscopic examination, the intestinal strictures contained mucosa and submucosa. Muscularis propria was not present within the webs (Figure 3). There was no evidence of inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or pathologic inflammation of the bowel or mesentery.

Postoperatively, bowel function was slow to return to normal. The patient had minimal bowel sounds and did not pass flatus until postoperative day (POD) 8. After POD 8, the patient progressed quickly; first, she tolerated a clear liquid diet and then a regular diet. On POD 10, the patient had an upper gastrointestinal barium study with a small intestine follow through, which showed normal motility, prompt emptying through the anastomosis, and barium reached the cecum within an hour. She was discharged on POD 10 and had no postoperative complications.

SBOs are most commonly caused by adhesions, hernias, neoplasms, or inflammatory strictures[1], with most caused by extraluminal adhesions due to postoperative inflammatory changes[2]. Although our patient had a history of abdominal surgery, she had no evidence of adhesions or extraluminal pathology. Her SBO was secondary to intraluminal strictures.

Intraluminal strictures are primarily caused by congenital defects, inflammation, ischemia, neoplasms or radiation. Congenital atresia is a common cause of neonatal intestinal obstruction. Jejunoileal atresia primarily results from intrauterine vascular events and tends to present early in life[3]. Late presentation of jejunal atresia has been reported; however, this is associated with other abnormalities[4]. It is unlikely that our patient had such a condition that had remained undiagnosed since birth.

Inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn's disease, may also cause intestinal strictures. Crohn's disease presents with full thickness inflammation of the intestinal wall. Obstruction occurs through either acute inflammation leading to occlusion, or through chronic inflammation leading to strictures. Our patient had no clinical or pathologic evidence of acute or chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Chronic inflammatory bowel disease strictures also tend to be longitudinal and localized to the ileum[5,6]; whereas our patient's strictures were distinct, concentric jejunal bands. Intestinal ischemia may also cause intestinal strictures and usually occurs in the presence of trauma, drug use, or vascular disease. The patient had no history of vascular disease or abdominal trauma, and reported no history of postprandial abdominal pain or fecal blood, which might indicate chronic intestinal ischemia. Cases of intestinal ischemia usually reveal some degree of mucosal ulceration and necrosis, with associated intestinal fibrosis and vascular disease[7]. A Medline search revealed no previous cases of sequential, stenotic strictures of the small intestine.

Intraoperatively, the intestine was viable and the mesenteric vessels had strong pulses. On pathologic examination, the patient had no evidence of mucosal irritation, intestinal fibrosis, or vascular pathology.

Malignancies may be another cause of intraluminal strictures. Benign tumors are the most common (i.e., leiomyomas); however, malignant lesions are more likely to have a symptomatic presentation. Melanoma is the most common metastatic malignancy of the small intestine and adenocarcinoma is the most common primary malignancy[8]. Additionally, radiation therapy used to treat intraabdominal masses may cause intestinal webs or scarring[9]. However, the patient had no history of malignancy or radiation therapy, and the pathology revealed no evidence of malignancy.

Chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) usage may also cause intraluminal pathology[10]. With newer imaging modalities such as capsule endoscopy, the small intestine is increasingly being recognized as a site of NSAID-induced toxicity. Mucosal damage is primarily mediated by a cycloxygenase-independent mechanism, but may also be caused by cycloxygenase-dependent mechanisms[10]. NSAID usage may cause either longitudinal or concentric strictures; however, our patient had no history of chronic NSAID usage, and there was no pathologic evidence of mucosal ulceration or inflammation.

Other possible sources of intestinal stricture are parasites (e.g., Ascaris) or bacteria (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis); however, the patient had no evidence of bacterial or parasitic infection.

In conclusion, in this report, we describe our finding of sequential, stenotic intraluminal strictures of the small intestine, which led to SBO. The unusual sequential, concentric nature of the strictures, along with the lack of evidence of inflammatory bowel disease, vascular disease, or malignancy is believed to be unique. This lack of a clearly defined etiology of the patient's strictures made this an intriguing case.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Yin DH

| 1. | 1 Markogiannakis H, Messaris E, Dardamanis D, Pararas N, Tzertzemelis D, Giannopoulos P, Larentzakis A, Lagoudianakis E, Manouras A, Bramis I. Acute mechanical bowel obstruction: clinical presentation, etiology, management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:432-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nagle A, Ujiki M, Denham W, Murayama K. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis for small bowel obstruction. Am J Surg. 2004;187:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dalla Vecchia LK, Grosfeld JL, West KW, Rescorla FJ, Scherer LR, Engum SA. Intestinal atresia and stenosis: a 25-year experience with 277 cases. Arch Surg. 1998;133:490-496; discussion 496-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Peetsold MG, Ekkelkamp S, Heij HA. Late presentation of a duodenal web in a patient with situs inversus and apple peel jejunal atresia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:301-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hurst RD, Molinari M, Chung TP, Rubin M, Michelassi F. Prospective study of the features, indications, and surgical treatment in 513 consecutive patients affected by Crohn's disease. Surgery. 1997;122:661-667; discussion 667-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Taschieri AM, Cristaldi M, Elli M, Danelli PG, Molteni B, Rovati M, Bianchi Porro G. Description of new "bowel-sparing" techniques for long strictures of Crohn's disease. Am J Surg. 1997;173:509-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee-Elliott C, Landells W, Keane A. Using CT to reveal traumatic ischemic stricture of the terminal ileum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:403-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gill SS, Heuman DM, Mihas AA. Small intestinal neoplasms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:267-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hatoum OA, Binion DG, Phillips SA, O'Loughlin C, Komorowski RA, Gutterman DD, Otterson MF. Radiation induced small bowel "web" formation is associated with acquired microvascular dysfunction. Gut. 2005;54:1797-1800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fortun PJ, Hawkey CJ. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the small intestine. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:169-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |