Published online Jan 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i4.633

Revised: October 18, 2006

Accepted: October 28, 2006

Published online: January 28, 2007

AIM: To retrospectively evaluate the preoperative diagnostic approaches and management of colonic injuries following blunt abdominal trauma.

METHODS: A total of 82 patients with colonic injuries caused by blunt trauma between January 1992 and December 2005 were enrolled. Data were collected on clinical presentation, investigations, diagnostic methods, associated injuries, and operative management. Colonic injury-related mortality and abdominal complications were analyzed.

RESULTS: Colonic injuries were caused mainly by motor vehicle accidents. Of the 82 patients, 58 (70.3%) had other associated injuries. Laparotomy was performed within 6 h after injury in 69 cases (84.1%), laparoscopy in 3 because of haemodynamic instability. The most commonly injured site was located in the transverse colon. The mean colon injury scale score was 2.8. The degree of faecal contamination was classified as mild in 18 (22.0%), moderate in 42 (51.2%), severe in 14 (17.1%), and unknown in 8 (9.8%) cases. Sixty-seven patients (81.7%) were treated with primary repair or resection and anastomosis. Faecal stream diversion was performed in 15 cases (18.3%). The overall mortality rate was 6.1%. The incidence of colonic injury-related abdominal complications was 20.7%. The only independent predictor of complications was the degree of peritoneal faecal contamination (P = 0.02).

CONCLUSION: Colonic injuries following blunt trauma are especially important because of the severity and complexity of associated injuries. A thorough physical examination and a combination of tests can be used to evaluate the indications for laparotomy. One stage management at the time of initial exploration is most often used for colonic injuries.

- Citation: Zheng YX, Chen L, Tao SF, Song P, Xu SM. Diagnosis and management of colonic injuries following blunt trauma. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(4): 633-636

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i4/633.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i4.633

Although the colon is often injured in case of penetrating abdominal trauma, a significant proportion of colonic injuries caused by road accidents is a grossly destructive blunt type associated with damage to multiple organs[1-3]. The diagnosis and management of blunt colon injuries are still debatable. The aim of this retrospective study was to evaluate the preoperative diagnostic methods and management of colonic injuries following blunt abdominal trauma.

All patients with colonic injuries caused by blunt trauma presenting to the Emergency Center of the Second Affiliated Hospital of School of Medicine of Zhejiang University between January 1992 and December 2005 were enrolled. The criterion for inclusion in the study was full thickness perforation of colon injuries requiring surgical repair. Data were collected on clinical presentation, investigations, diagnostic methods, associated injuries, operative management, morbidity and mortality.

Haemodynamic status was determined based on their heart rate and systolic blood pressure (BP) on admission. A systolic BP equal to or < 90 mmHg on admission was interpreted as haemodynamic instability or presence of shock. The time from injury to operation was recorded. The site of colon injury (right colon defined as the right of the middle colic vessels, left colon the left of the vessels) and major associated injuries of the head, thorax, pelvis, axial skeleton, major blood vessels and long bones were recorded.

The severity of colon injury was graded according to the colon injury scale (CIS) score[4]. CIS score was definited as follows: grade 1: contusion and serosal tear without devascularization, grade 2: laceration of less than 50% of the wall, grade 3: laceration of 50% or greater of the wall, grade 4: 100% transection of the wall, and grade 5: complete transection with tissue loss and devascularization, an advanced grade for multiple injuries to the colon. The degree of faecal spillage (the gross extent of intra-abdominal faecal contamination) was categorized as mild: stool contamination on local or one quadrant, moderate: stool contamination on 2 to 3 quadrants, and severe: stool contamination on all four quadrants[5].

All patients were resuscitated and received intravenous antibiotics in the emergency room. The discretion of operative options was based on Stone’s exclusion factors for primary repair[6] and surgeons’ experience. The outcome variables of the study included colonic injury-related mortality and abdominal complications (anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal abscess or peritonitis, and colon obstruction or necrosis, if it was judged to be directly related to the colonic trauma).

All analyses were carried out by SPSS 12.0 statistical software. Independent predictors for colostomy and post-operative complications were determined by entering potential confounders into a multivariate stepwise (backward elimination) logistic regression. Variables considered in the model for colostomy included age, mechanism of injury, shock on admission, CIS, degree of peritoneal faecal contamination, location of colon injury, and associated intra-abdominal injury. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 82 patients were included in this study. There were 77 males (93.9%) and 5 females (6.1%). Their age ranged 15-67 years with a mean of 37.6 years. Colonic injury was found in 57 patients (69.5%) due to motor vehicle accidents, in 18 (22.0%) due to building accidents, in 6 (7.3%) due to criminal assault, and in 1 (1.2%) due to burst injury.

Abdominal signs could not be detected in 8 cases (9.8%) because of head injuries, intoxication or sedation. Seventy patients (94.6%) had moderate to severe abdominal tenderness, 18 (24.3%) had diffuse peritonism, 23 (28.0%) had shock on admission. In addition, hematuria was found in 12 patients (14.6%), paraplegia in 2 (2.4%), aerocele of scroticles in 2 (2.4%) patients. Plain abdominal radiograph was performed to find pneumoperitoneum and intestinal obstruction in 54 patients. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) or paracentesis was performed in 65 cases, which was positive in 43 cases (noncongested blood in 20 cases, pus in 23 cases). Abdominal ultrasonography (US) and computed tomography (CT) were performed in 58 and 10 cases respectively. Among them, 12 were diagnosed as gastrointestinal injury with intraperitoneal free fluid.

Fifty-eight patients (70.3%) were found to have one or more associated injuries (Table 1). The most commonly associated intra-abdominal injury occurred in the small bowel (51.2%), followed by in the speen, liver, and kidney. Multiple colonic wounds were observed in 4 cases (4.9%), Isolated colon injury in 20 cases (24.4%). The range of intra-abdominal organs injured was 1-4, with a mean of 2.3.

| n | |

| Intra-abdominal | |

| Small bowel | 42 |

| Spleen | 11 |

| Liver | 9 |

| Kidney | 4 |

| Urinary bladder | 3 |

| Pancreas | 2 |

| Ureter | 2 |

| Stomach | 2 |

| Duodenum | 1 |

| Diaphragm | 1 |

| Extra-abdominal | |

| Head | 12 |

| Chest | 6 |

| Vascular peripheral | 5 |

| Fracture vertebral lumbar | 5 |

| Fracture pelvis | 2 |

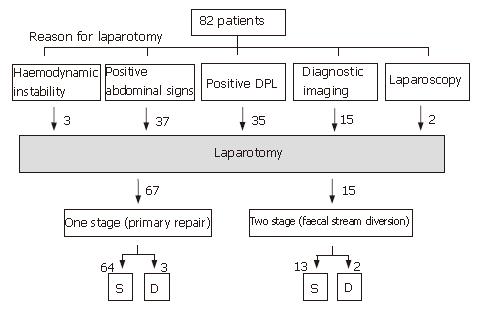

Seven patients (8.5%) underwent immediate laparotomy (< 2 h after injury), 4 for severe peritonitis and 3 due to haemodynamic instability. Laparotomy was performed between 2 h and 6 h after injury in 62 cases (75.6%). Of them, 33 had a laparotomy because of abdominal signs with evidence of peritonitis at admission or during observation, 35 because of positive DPL or paracentesis. Eighteen (51.4%) of these patients had more than one significant intra-abdominal injury. An abdominal CT scan or US imaging with diagnostic or suspicious findings was the main reason for laparotomy in 15 cases (18.3%). Colonic injuries were found in 2 patients at diagnostic laparoscopy (Figure 1).

A total of 87 colonic injuries were found in 82 patients. The most often wounded site was located in the transverse colon (32 cases, 36.8%). The right colon injury was found in 21 cases, the descending colon injury in 16, the sigmoid colon injury in 13, and the intraperitoneal rectum injury in 5. The mean CIS score was 2.8 ± 1.2. The degree of faecal contamination was classified by the operating surgeon as mild in 18 cases (22.0%), moderate in 42 (51.2%), severe in 14 (17.1%), and unknown in 8 (9.8%).

Therapeutic options were considered: two-stage management for those with any type of faecal stream diversion, while one stage management for those undergoing primary repair of the injured colon with or without anastomosis. The successful rate for colonic wounds without diversion was 81.7% (67 cases). Primary repair was undertaken in 37 cases with resection and primary anastomosis in a further 30 cases. Two-stage operation was performed in 15 cases (18.3%): repair and protective ostomy in 11 cases, exteriorisation of the repaired bowel in 3 cases, Hartmann’s operation in 1 case. The overall mortality rate was 6.1% (5/82). The overall incidence of colonic injury-related abdominal complications was 20.7% (17/82). The most common complications were anastomotic leak (12 cases), intra-abdominal abscess (10 cases), wound infection (12 cases) and colon obstruction or necrosis (4 cases). The only independent predictor of complications was the degree of peritoneal faecal contamination (P = 0.02). There was no significant correlation between age, mechanism of injury, shock on admission, location of colon injury, therapeutic options and outcome in terms of morbidity and mortality.

Injuries of the hollow viscera are far less common in blunt abdominal trauma than in penetrating abdominal trauma. Blunt abdominal trauma accounts for approximately 5% to 15% of all operative abdominal injuries[3,7]. The majority of colonic injuries caused by penetrating trauma are dominant[1-3,5]. Nevertheless, in our experience about 6.5% of patients with blunt trauma at admission had injuries to the colon and rectum, which is slightly higher than the reported 5%[8]. Despite their infrequence, traumatic blunt injuries to the colon are extremely destructive and generally associated with damage to multiple organ systems, making diagnosis and treatment difficult. It was reported that delayed management of colonic injuries results in a high incidence of morbidity[9]. Therefore, further researches on guidelines for the diagnosis and surgical management of colonic injuries following blunt trauma are especially important.

No clinical investigations are available to compare with gastrointestinal tract injuries. Moreover, clinical assessment can be unreliable in patients following blunt trauma due to distracting injuries, head and spinal cord injuries, and shock. Less than 50% of gastrointestinal tract injuries resulting from blunt trauma are reported to have sufficient clinical findings to indicate the need for laparotomy[10]. In this study, 3 patients with unstable haemodynamics undergoing immediate laparotomy (< 2 h) showed marked evidence for abdominal injury. The other 4 patients with gross abdominal distension and marked tenderness were also immediately operated. In 6 patients presented within two hours, abdominal signs were vague at initial evaluation but became marked over a few hours at a repeated examination. The finding of abdominal signs in the other 27 cases presented between two and six hours after trauma resulted in laparotomy. Tenderness or other abdominal findings were usually apparent within 24 h.

Physical examination and diagnostic tests can be used to evaluate patients with blunt abdominal trauma, including DPL, US, CT, and diagnostic laparoscopy. Speed and efficiency are important factors in the performing such tests[3]. It is reported that peritoneal lavage cell count may also be useful in early detection of hollow viscus injury[11,12]. Although DPL is sensitive in identifying haemoperitoneum and associated hollow viscus injury, it has been criticised for its higher rate of non-therapeutic laparotomy (NTL) and inconvenience in practice[12]. In this study, the presence of positive DPL or paracentesis was an important clinical finding. The routine use of diagnostic celiocentesis to detect possible intra-abdominal injuries in cardiovascularly stable patients has been used to differentiate between injuries that require a therapeutic laparotomy and those that do not[13]. Suspicious diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract injuries was indicated in 35 cases in this study. However, the diagnostic rate of colonic injuries by DPL or celiocentesis was decreased over the study period, which may be due to the increased use of imaging techniques to assess haemodynamically stable trauma patients.

US is convenient, cheap and noninvasive. A positive study is defined as evidence of free fluid or solid-organ parenchymal injury. Abdominal CT is also useful in the diagnosis of abdominal injuries as it accurately delineates solid organ injuries and retroperitoneal lesions. While some advocate limiting imaging tests to evaluation of patients with DPL-positive results and haemodynamic stability, US and CT remain the preferred tool in the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma[3,14]. The accuracy of abdominal US for evaluating blunt abdominal trauma is comparable to the reported accuracy[15]. However, only 10 out of the 58 scans in our study could diagnose intra-abdominal gastrointestinal tract injuries with 5 being suspicious of a significant intra-abdominal injury. Some patients with free fluid but no evidence of a solid viscus injury might presumably be overlooked.

Although the role of laparoscopy in abdominal trauma is controversial[16], diagnostic laparoscopy has been introduced in our emergency center. Its indications have expanded from identifying the causative pathology of acute abdominal pain to avoidance of unnecessary laparotomies, treatment of intra-abdominal lesions, and can be used as a resource for evaluating blunt abdominal trauma. Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed in 2 cases in our study and some direct indications for colonic injuries (such as faecal spillage, colon rupture) were found in both cases. Take together, the indications for laparotomy were determined according one of the following findings: haemodynamic instability with reasonable clinical suspicion of an intra-abdominal cause, positive abdominal signs, positive DPL, positive diagnostic imaging and abdominal finding by laparoscopy.

The management of colonic injuries has changed significantly from ‘‘faecal diversion dogma’’ to primary repair[2,3]. Although several studies showed that diversion is not mandatory, additional considerations in management should be taken into account regarding grossly destructive colon injuries. In our study, mild, moderate and severe faecal contamination was found in 22.0%, 51.2%, and 17.1% of patients, respectively at laparotomy. In 15 patients (18.3%), primary laparotomy was terminated before the completion of definitive surgery (abbreviated laparotomy or damage control).

It was reported that the mortality of colonic injuries have declined to 2%-12%[1,3,17]. Primary closure or resection and anastomosis can be used in patients with colonic injury. The results are generally favorable, due to the advances in intensive care techniques and antibiotic therapy. Primary repair reduces operation and postoperative complications, avoids a second operation, stoma complications, and the financial burden related to colostomy care. A number of factors have been traditionally accepted to be associated with higher mortality and morbidity of primary colonic repair. It was reported that patients should be excluded from primary repair in the presence of shock, major blood loss, > two organs injured, faecal contamination higher than ‘mild’, delay of repair > 8 h and destructive wounds of the colon or abdominal wall requiring resection[6]. The grade of colonic injuries trends to be independently associated with intra-abdominal complications. In our study, the overall mortality rate was 6.1%. Although neither grade of injury nor ostomy formation demonstrated a significant impact on morbidity, peritoneal faecal contamination has shown its significant predictive value for complications. We advocate that peritoneal faecal contamination should be thoroughly removed during operation to reduce postoperative abdominal septic morbidities. There was no difference between patients with primary repair and faecal stream diversion. However, other organ injuries must be kept in mind. Colostomy may be indicated due to unusual conditions, such as intramural hematomas causing compression ischemia and delayed perforation, mesenteric hematomas causing vascular compression with subsequent infarction, and perforations in omentum or other surrounding organs[3]. All together, the decision for a primary anastomosis, especially after segmental resection in the descending colon, should be individualized according to the injuries in different patients.

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Tzovaras G, Hatzitheofilou C. New trends in the management of colonic trauma. Injury. 2005;36:1011-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bowley DM, Boffard KD, Goosen J, Bebington BD, Plani F. Evolving concepts in the management of colonic injury. Injury. 2001;32:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cleary RK, Pomerantz RA, Lampman RM. Colon and rectal injuries. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1203-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malangoni MA, Jurkovich GJ, Champion HR, Gennarelli TA, McAninch JW, Pachter HL, Shackford SR, Trafton PG. Organ injury scaling, II: Pancreas, duodenum, small bowel, colon, and rectum. J Trauma. 1990;30:1427-1429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xu SM, Zheng YX, Gong WH, Wang P. Management of colorectal injuries. Zhonghua Putong Waike Zazhi. 2004;19:337-339. |

| 6. | Stone HH, Fabian TC. Management of perforating colon trauma: randomization between primary closure and exteriorization. Ann Surg. 1979;190:430-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ricciardi R, Paterson CA, Islam S, Sweeney WB, Baker SP, Counihan TC. Independent predictors of morbidity and mortality in blunt colon trauma. Am Surg. 2004;70:75-79. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wisner DH, Chun Y, Blaisdell FW. Blunt intestinal injury. Keys to diagnosis and management. Arch Surg. 1990;125:1319-1322; discussion 1322-1323;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ujhelyi M, Hoyt RH, Burns K, Fishman RS, Musley S, Silverman MH. Nitrous oxide sedation reduces discomfort caused by atrial defibrillation shocks. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004;27:485-491. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hughes TM, Elton C, Hitos K, Perez JV, McDougall PA. Intra-abdominal gastrointestinal tract injuries following blunt trauma: the experience of an Australian trauma centre. Injury. 2002;33:617-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Olsen WR, Hildreth DH. Abdominal paracentesis and peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1971;11:824-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nagy KK, Roberts RR, Joseph KT, Smith RF, An GC, Bokhari F, Barrett J. Experience with over 2500 diagnostic peritoneal lavages. Injury. 2000;31:479-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang P, Zheng YX, Xu SM, Cui L. Diagnosis and management of 96 cases with colorectal injuries. Zhonghua Jizhen Yixue Zazhi. 2003;12:487-489. |

| 14. | Marco GG, Diego S, Giulio A, Luca S. Screening US and CT for blunt abdominal trauma: a retrospective study. Eur J Radiol. 2005;56:97-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nural MS, Yardan T, Güven H, Baydin A, Bayrak IK, Kati C. Diagnostic value of ultrasonography in the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2005;11:41-44. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Chelly MR, Major K, Spivak J, Hui T, Hiatt JR, Margulies DR. The value of laparoscopy in management of abdominal trauma. Am Surg. 2003;69:957-960. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Burch JM. Injury to the colon and rectum. Trauma. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 1999; 763-782. |