Published online Jan 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i4.579

Revised: July 25, 2006

Accepted: December 19, 2006

Published online: January 28, 2007

AIM: To investigate the use of high dose consensus-interferon in combination with ribavirin in former iv drug users infected with hepatitis C.

METHODS: We started, before pegylated (PEG)-interferons were available, an open-label study to investigate the efficacy and tolerability of high dose induction therapy with consensus interferon (CIFN) and ribavirin in treatment of naiive patients with chronic hepatitis C. Fifty-eight patients who were former iv drug users, were enrolled receiving 18 μg of CIFN daily for 8 wk, followed by 9 μg daily for up to wk 24 or 48 and 800 mg of ribavirin daily. End point of the study was tolerability and eradication of the virus at wk 48 and sustained virological response at wk 72.

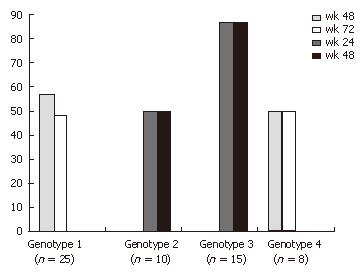

RESULTS: More than 62% of patients responded to the treatment with CIFN at wk 24 or 48, respectively, showing a negative qualitative PCR [genotype 1 fourteen patients (56%), genotype 2 five (50%), genotype 3 thirteen (87%), genotype 4 four (50%)]. Forty-eight percent of genotype 1 patients showed sustained virological response (SVR) six months after the treatment.

CONCLUSION: CIFN on a daily basis is well tolerated and side effects like leuko- and thrombocytopenia are moderate. End of therapy (EOT) rates are slightly lower than the newer standard therapy with pegylated interferons. CIFN on a daily basis might be a favourable therapy regimen for patients with GT1 and high viral load or for non-responders after failure of standard therapy.

- Citation: Witthoeft T, Fuchs M, Ludwig D. Recent IV-drug users with chronic hepatitis C can be efficiently treated with daily high dose induction therapy using consensus interferon: An open-label pilot study. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(4): 579-584

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i4/579.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i4.579

Under physiological conditions, interferon-α (IFN-α) is a key cytokine produced by virtually all cells in the mammalian organism in response to a variety of bacterial and viral stimuli. In response to viral infection, IFN-α produced by the infected target cells induces a number of cellular genes involved in inhibition of viral replication. In addition, IFN-α is secreted by stimulated NK-cells and T-cells and exerts a multitude of immune stimulatory effects of innate and adaptive immunity[1].

The current standard of treating patients with chronic hepatitis C infection is using IFN-α with or without ribavirin and great advances have been achieved[2]. So far two allelic α-2 species, interferon α-2a and interferon α-2b, have been used. Introduction of pegylated IFN in 2001 showed a slight increase in the overall sustained virological response rates (approximately 55%) compared to conventional IFN-α[3,4]. However, recent studies showed that these response rates depend on several factors, including HCV genotype, baseline viral load, ethnicity, body weight and presence of advanced liver disease[3]. More than 75% of patients in western Europe are infected with genotype 1 often showing a high viral load and these patients are so called “difficult to treat” and therefore remain at risk not to respond to standard HCV treatments[5].

Before pegylated IFN was available, we introduced a study using IFN-alfacon-1, a second-generation cytokine that was engineered to contain the most frequently occurring amino acids among the non-allelic IFN-α subtypes in humans[6]. In vitro studies showed that IFN-alfacon-1 induces a more dramatic decrease of HCV-RNA compared to IFN-2b[7] and shows a 10-time higher antiviral efficacy[6]. The rationale for daily dosing in our study was the fact that serum levels of IFN-α given three times a week were dropping almost below the detection limit every other day and therefore reducing the antiviral capability. High initial dosing would reduce the viral load even further and early virological response (EVR) would lead to a higher SVR than 9 μg daily[8]. Taking these results into account, the aim of this study was to look at the efficacy, tolerability and safety of high dose IFN-alfacon-1 plus ribavirin combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

Patients aged 18 years and older with a serological and histological diagnosis of chronic HCV infection were asked to participate in the study. All patients were naïve to antiviral treatment and were recent iv drug users referred by a clinic with a detoxification program. Each individual had to be off drugs for at least 4 to 6 mo, and replacement medication (e.g. buprenorphine) was allowed. The local ethics committee approved the study and informed consent of patients was obtained prior to serological and histological testing and antiviral therapy. The study protocol was in accordance to the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion criteria required that patients had detectable serum HCV-RNA and liver biopsy compatible with a diagnosis of chronic HCV infection. Exclusion criteria included decompensated liver disease, hemoglobin < 12 g/dL for men and women, white blood cell count < 3000/μL, neutrophil count < 1500/μL, and platelet count < 70 000/μL. Patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or HIV infection were excluded. Similarly, patients with antinuclear antibody ≥ 160 or diagnosis of other chronic liver diseases (hemochromatosis, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s disease, or other chronic liver diseases), or who had prior organ transplantation or hyper- or hypothyroidism were also excluded. A history of major depression or ongoing alcohol or drug abuse within the previous 6 mo, renal insufficiency, hemophilia, poorly controlled diabetes, cardiac disease, immunologically mediated diseases, active seizure disorders or brain injury requiring medication for stabilization and pregnancy were further criteria for not being included in the study. Eleven patients were on replacement medication including methadone and codeine.

The study was a mono-center clinical trial with consecutive and prospective enrolment. All patients were naïve to antiviral therapy including IFN and ribavirin. All patients received a high induction therapy with IFN-alfacon-1, 18 μg (Inferax®; Yamanouchi Pharma GmbH, Heidelberg, now Astellas Pharma GmbH, Munich) subcutaneously daily for eight weeks, followed by 9 μg subcutaneously daily until the end of treatment. Ribavirin (Meduna Pharma GmbH, Isernhagen, Germany), 800 mg daily, was administered bid over the whole treatment period. If HCV RNA levels were detectable after 24 wk, treatment was considered as failure and stopped; if HCV RNA was undetectable at wk 24, treatment was continued for a total of 48 wk in HCV genotypes 1 and 4. Treatment of genotypes 2 and 3 was stopped after 24 wk in general. After therapy was ended, patients were followed up for an additional 24 wk.

It was initially planned to treat 100 patients. However, after 58 subjects were enrolled, recruitment was suspended because of ethical concern following the release of pegylated IFN α-2b which became the standard of treatment.

HCV genotyping was performed using the INNO-LiPA HCV II kit assay (Innogenetics, Gent, Belgium).

Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction was performed using the Cobas Amplicor hepatitis C monitor test (v2.0, Roche Diagnostics, Grenzach-Wyhlen, Germany). The results of HCV RNA are expressed as international units per millilitre based on published formulas where 2 000 000 copies are equivalent to 800.000 IU/mL[9].

The primary end point of the study was assessment of sustained virological response rate defined as loss of detectable HCV RNA by RT-PCR at wk 72 [24 wk after end of therapy (EOT)]. A secondary end point was assessment of the sustained biochemical response (SBR), defined as normalization of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) at wk 72. No second histological end point was sought. Early virological response (EVR) at wk 4 was not determined.

Safety and tolerability assessments were performed at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 wk of therapy and then 12 and 24 wk post-treatment. All adverse events, laboratory test-results, discontinuation or withdrawal due to adverse events, and dose reduction were recorded and evaluated.

Analysis was based on the intent to treat 48 patients enrolled in the study. Data were described by rates, means with standard deviation, medians, and ranges. In addition, multivariate step-wise logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors from baseline characteristics which were associated with SVR in univariate analysis. All P-values reported were two-sided and P-values below 5% were considered statistically significant.

Between July 2000 and May 2003, 58 patients with chronic HCV infection were enrolled at our site in Luebeck. Of these patients, 57% were men and 43% women. All patients were of Caucasian origin and the mean age was 36 years. Ninety percent of the patients showed a histological diagnosis of chronic hepatitis and only 2% showed histologically cirrhosis that was deemed clinically compensated. The mean serum HCV RNA concentration was 617.000 IU/mL. Fifty-two percent of the patients were infected with genotype 1. Genotypes 2 and 3 were present in 39% of the patients and 4% of the patients showed genotype 4. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristics | |

| Mean age, years, (range) | 36 (22–62) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 33 |

| Female | 25 |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 48 (100) |

| ALT, IU/L (range) | 57 (9-263) |

| HCV-RNA level, > 800.000 IU/mL | 23 (40) |

| Mean level, IU/mL | 615.000 |

| HCV genotype | |

| 1, 1a, 1b, 4 | 32 (55) |

| 2a, 2b, 3 | 24 (42) |

| Not available | 2 (3) |

| HCV genotype 1 and HCV-RNA > 800.000 IU/mL | 19 (33) |

| Liver biopsy (available in 56 out of 58 patients) | |

| No chronic hepatitis | 10 (17) |

| Chronic hepatitis | 43 (74) |

| Cirrhosis | 3 (5) |

| Co-medication | |

| Methadone | 4 (7) |

| Codeine | 7 (12) |

Overall, 62% of the patients showed a sustained virological response (SVR) at the end of therapy, whereas 16 individuals did not respond to the therapy. ALT levels dropped significantly from initially elevated levels during the first 12 wk of therapy, whereas AST and bilirubin were stable in the normal laboratory range. Fifty-six percent and 50% of the patients with genotypes 1 and 4, respectively, showed a virological response at the end of treatment, while 48% and 48% respectively, reached a sustained virological response at wk 72. In the group of patients with easy to treat genotypes 2 and 3, 50% and 87% respectively, achieved a negative HCV-PCR at the end of treatment and no relapse occurred in these 19 patients until wk 48 (Figure 1). The patients with a low viral load (< 800.000 IU/mL) initially had a slightly greater chance of achieving SVR compared to those with a high viral load (48% vs 40%) irrespective of their genotype (Table 2). Women responded slightly better to therapy than men. The drop in viral load was accompanied with a significant decrease in ALT levels throughout the first three months of therapy (57 U/L to 22 U/L). AST levels were in their normal range at the beginning of treatment and there was only little if any further normalisation (25 U/L to 17 U/L). In some patients bilirubin was slightly elevated as well but showed normal levels at the end of therapy (data not shown). There was no positive correlation between either genotype or ALT or SVR (data not shown).

| All genotypes | |

| < 800.000 IU/mL | 23/33 (70) |

| ≥ 800.000 IU/mL | 13/25 (52) |

| Genotype 1 | |

| < 800.000 IU/mL | 5/6 (83) |

| ≥ 800.000 IU/mL | 9/19 (47) |

| Non-genotype 1 | |

| < 800.000 IU/mL | 18/27 (67) |

| ≥ 800.000 IU/mL | 4/6 (67) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 16/33 (49) |

| Female | 14/25 (56) |

Neither consensus interferon (CIFN) nor ribavirin dosing had to be modified throughout the therapy in any patient.

Co-medication with either methadone or codeine did not play a role in treating patients with HCV. Neither dosage nor application of replacement medicine had to be adjusted. The patients on replacement medication did not succeed in regard to SVR compared to those without methadone or codeine (data not shown). Ninety-two percent of the patients, who did achieve sustained virological response, took more than 80% of medication throughout the whole treatment period, demonstrating a remarkably high adherence to antiviral therapy.

However, only 2 out of all patients (all genotype 1) with negative PCR at wk 48 (EOT) had a virological relapse during the follow-up period between wk 48 and 72.

Seven patients showed a relapse of their intravenous drug abuse prior to the end of therapy and one 28-year old male patient died due to a heroin overdose. Six patients stoped therapy due to treatment-related side-effects (bleeding due to low platelets). Two patients did not show up for follow-up visits during antiviral treatment. No patient showed evidence of hypocalcemia, previously reported for daily dosing of CIFN[10]. Liver function in all patients was stable as measured clinically and by testing of coagulation function and serum albumin (data not shown).

There was one serious adverse event 8 wk after beginning of therapy, leading to a death due to an overdose of intravenous heroin abuse. Six patients showed a restart of their iv drug abuse while on combination therapy. One patient developed a major depression, one female patient showed a significant drop in platelets (43.000/μL), one showed recurrent epistaxis (89.000/μL) and one male patient showed a long- lasting episode of arthritis and suicidal thoughts. Otherwise dose modifications due to adverse events were not necessary in any patient.

The spectrum of side effects of daily high dose induction therapy with CIFN was similar to previous trials with IFN and ribavirin. All the 58 patients were included in safety analysis. All the patients experienced flu-like symptoms (100%). Most of them experienced fatigue (93%), headache (91%), cough (72%), and mood disorders (87%). Two patients experienced bleeding disorders due to low platelets [e.g. bleeding gingivitis (101/nL), epistaxis (89/nL)] and one patient was taken off antiviral medication due to a significant drop of WBC (Table 3). One patient did not receive further treatment at wk 8 due to impaired vision, myalgia, and suicidal thoughts. None of the patient experiencing mood disorders required any psychopharmacological co-medication.

| Event | n |

| Neutropenia | |

| < 1500 | 21 |

| < 1000 | 10 |

| < 500 | 1 |

| Anemia | |

| < 10.5 g | 1 |

| < 8.5 g | 0 |

| Platelets | |

| < 100.000 | 4 |

| < 50.000 | 0 |

In patients with significant neutropenia, this side effect occurred mostly during wk 6 and 8 of therapy, after being treated with high dose CIFN for the first 8 wk. GMCSF was not administered since low neutrophil count always returned to almost normal level in all patients by reducing daily CIFN dosing to 9 μg daily according to the study protocol. Neither platelets nor blood transfusion was given in patients with low platelets due to CIFN or anemia due to ribavirin.

One severe adverse event occurred due to the relapse of intravenous drug use followed by a lethal overdose injection. Five other patients took intravenous drugs as well and were immediately taken off the antiviral study drugs.

Because personal mental and physical components of health of a patient undergoing such an antiviral therapy is important, each patient was requested to answer a widely accepted questionnaire (IQOLA SF-36, German Acute version 1.0) with respect to the quality of life at wk 0 and 12.

There was a decrease in well being after 12 wk of therapy, but a significant number felt better after finishing the high induction treatment period. The physical activity in most patients was slightly impaired 3 mo after therapy (Table 4). There was a significant increase in emotional distress at wk 12 compared to wk 0, possibly due to CIFN. More patients experienced physical pain (70%), depression (50%), unhappiness (50%) and tiredness (51%) at wk 12, while personal contact to friends and relatives was not influenced by therapy (29%). Due to the side effects, fewer people (35%) felt healthy three months after the beginning of treatment and 68% did not feel healthy during the upcoming treatment phase.

| wk 0 | wk 12 | |

| Personal feeling | Very good (76) | Good (63) |

| Personal feeling compared to last week | Good (77) | Better (55) |

| Impaired physical activity | Never (90) | Slightly (77) |

| Impaired physical activity compared to last week | Never (88) | Slightly (73) |

| Emotional problems | Never (93) | Never (48) |

| Pain | None (90) | None (30) |

| Pain last week | None (83) | None (54) |

| Feeling depressed | Never (88) | Seldom (45) |

| Feeling happy | Often (85) | Sometimes (50) |

| Feeling tired | Seldom (77) | Sometimes (51) |

| Impaired personal contact to relatives and friends due to disease | Never (88) | Seldom (71) |

| “I’m feeling fit like others” | Mostly (94) | No (37) |

| “I’m feeling healthy” | Mostly (78) | No (65) |

| “I expect not to feel healthy” | Do not know (44) | No (32) |

Chronic hepatitis C virus infection is responsible for an increase in morbidity and mortality. This is the first study on the treatment of naïve patients with chronic HCV infection with high-dosing of IFN-alfacon-1 in combination with ribavirin. Recent intravenous drug addicts can be successfully treated for HCV and the response rates are as good as in patients without iv drug history.

The goal of our study was to address the issue of efficacy, tolerability and safety of daily high dose induction therapy with consensus-interferon (CIFN) and ribavirin in naïve HCV-infected patients. However, the usually recommended dosing of CIFN is 9 μg, three times a week at the beginning of the trial. Ribavirin was given on a daily basis at 800 mg, irrespective of the genotyping. Weight-based dosing of ribavirin for therapy in HCV genotypes 1 and 4 has been introduced after several studies were conducted in 2001[3].

All patients received a higher dosage of interferon (18 μg of CIFN subcutaneously daily for up to 8 wk followed by 9 μg daily) in combination with ribavirin for 24 or 48 wk. The patients were then carefully followed up for an additional 24 wk.

The overall response rate was 62 % showing a sustained virological response (SVR) 24 wk after the EOT. There was a slight difference (P < 0.05) in response rates in regard to the initial viral load. The patients with a low viral load (< 800.000 IU/mL) responded better (70% vs 52%) than those with a high viral load. These results are comparable to data (54%) obtained with pegylated α-2b/ribavirin[3].

There was a significant difference (P < 0.01) in response rates for the patients with a high viral load. With respect to genotyping, the patients with non-genotype 1 showed a SVR rate of 67% compared to 47% in the genotype 1 patients, even though the number of patients in the later group was quite small. In contrast, different response rates were obtained for HCV-infected patients presenting a low viral load initially. The non-genotype 1 patients showed a 64% SVR rate compared to 83% for the genotype 1-infected individuals. This fact might be explained by the small number of patients presenting genotype 1 and low-viral load. Overall, the patients with genotype 1 and high viral load showed an acceptable response rate, which is in accordance to Sjögren et al[11], showing a higher response rate for this population treated with CIFN and ribavirin instead of pegylated interferon α-2b and ribavirin (46% vs 14%).

In this treatment-naïve patient population, neither baseline ALT nor genotype was significantly associated with SVR, similar to other reports comparing treatment of non-responders with either CIFN or pegylated interferon α-2b in combination with ribavirin[15].

Adherence to therapy is another important issue for success of treatment[12]. Therapy with a wide range of side effects is less favourable and therefore less successful in achieving SVR. In our study, the overall adherence was good and comparable to previous studies[13]. It is known that HCV-1-infected patients maintained on > 80% of their interferon or peginterferon α-2b and ribavirin dosage for the duration of treatment have enhanced sustained response rates. In addition, some results suggest that adherence enhances the likelihood of achieving an initial virologic response[12].

However, the rate of reuse of intravenous drugs in almost 10% of patients (6 out of 58 patients) is substantial and accounts partly for the high drop-out rate in our study even though former iv drug users had to be off active drug use for at least 6 mo prior to study enrolment.

The increased side effects in patients treated with CIFN at a high induction rate (18 μg vs 9 μg daily) can result in a higher drop out rate[14,15]. The initial rapid decline in viral load at wk 4 is counteracted by increased side effects, resulting in a lesser SVR rate, at least in non responders[15].

In conclusion, the safety and tolerability profile of this treatment is reasonable in a certain subset of patients, but might be difficult to tolerate in some individuals, resulting in discontinuation of therapy. However, these data suggest that CIFN may be safely combined with ribavirin and enhance the sustained response rate when close monitoring of side-effects and laboratory results are obeyed[10]. Patients with chronic hepatitis C and genotype 2 or 3 should be treated with pegylated interferon α-2a or 2b in combination with ribavirin for up to 24 wk[16], respectively. In difficult-to-treat patients with genotype 1 and high viral load, a daily therapy regimen with consensus interferon in combination with ribavirin might be of choice as well as in non-responders to combination therapy[15,17].

This is the first study showing that recent iv drug users can be safely and successfully treated for HCV if they are closely monitored.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Lu W

| 1. | Pestka S. The human interferon-alpha species and hybrid proteins. Semin Oncol. 1997;24:S9-4-S9-17. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H, Manns MP. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with PEGylated interferon and ribavirin. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2002;4:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, Goodman ZD, Koury K, Ling M, Albrecht JK. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4736] [Cited by in RCA: 4558] [Article Influence: 189.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Gonçales FL, Häussinger D, Diago M, Carosi G, Dhumeaux D. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4847] [Cited by in RCA: 4747] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Di Bisceglie AM, Hoofnagle JH. Optimal therapy of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36:S121-S127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Blatt LM, Davis JM, Klein SB, Taylor MW. The biologic activity and molecular characterization of a novel synthetic interferon-alpha species, consensus interferon. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1996;16:489-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tong MJ, Reddy KR, Lee WM, Pockros PJ, Hoefs JC, Keeffe EB, Hollinger FB, Hathcote EJ, White H, Foust RT. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with consensus interferon: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Consensus Interferon Study Group. Hepatology. 1997;26:747-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lam NP, Neumann AU, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, Perelson AS, Layden TJ. Dose-dependent acute clearance of hepatitis C genotype 1 virus with interferon alfa. Hepatology. 1997;26:226-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pawlotsky JM, Bouvier-Alias M, Hezode C, Darthuy F, Remire J, Dhumeaux D. Standardization of hepatitis C virus RNA quantification. Hepatology. 2000;32:654-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pockros PJ, Reindollar R, McHutchinson J, Reddy R, Wright T, Boyd DG, Wilkes LB. The safety and tolerability of daily infergen plus ribavirin in the treatment of naíïve chronic hepatitis C patients. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:55-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sjogren MH, Sjogren R, Holtzmuller K, Winston B, Butterfield B, Drake S, Watts A, Howard R, Smith M. Interferon alfacon-1 and ribavirin versus interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:727-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McHutchison JG, Manns M, Patel K, Poynard T, Lindsay KL, Trepo C, Dienstag J, Lee WM, Mak C, Garaud JJ. Adherence to combination therapy enhances sustained response in genotype-1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1061-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 750] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fattovich G, Zagni I, Minola E, Felder M, Rovere P, Carlotto A, Suppressa S, Miracolo A, Paternoster C, Rizzo C. A randomized trial of consensus interferon in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2003;39:843-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moskovitz DN, Manoharan P, Heathcote EJ. High dose consensus interferon in nonresponders to interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin with chronic hepatitis C. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:479-482. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Cornberg M, Hadem J, Herrmann E, Schuppert F, Schmidt HH, Reiser M, Marschal O, Steffen M, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H. Treatment with daily consensus interferon (CIFN) plus ribavirin in non-responder patients with chronic hepatitis C: a randomized open-label pilot study. J Hepatol. 2006;44:291-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | von Wagner M, Huber M, Berg T, Hinrichsen H, Rasenack J, Heintges T, Bergk A, Bernsmeier C, Häussinger D, Herrmann E. Peginterferon-alpha-2a (40KD) and ribavirin for 16 or 24 weeks in patients with genotype 2 or 3 chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:522-527. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Böcher WO, Schuchmann M, Link R, Hillenbrand H, Rahman F, Sprinzl M, Mudter J, Löhr HF, Galle PR. Consensus interferon and ribavirin for patients with chronic hepatitis C and failure of previous interferon-alpha therapy. Liver Int. 2006;26:319-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |