Published online Oct 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i39.5285

Revised: August 8, 2007

Accepted: September 12, 2007

Published online: October 21, 2007

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is generally considered safe with a low rate of serious complications. However, dislocation of the PEG-tube into the duodenum can lead to serious complications. An 86-year old Japanese woman with PEG-tube feeding sometimes vomited after her family doctor replaced the PEG-tube without radiologic confirmation. At her hospitalization, she complained of severe tenderness at the epigastric region and the PEG-tube was drawn into the stomach. Imaging studies showed that the tip of PEG-tube with the inflated balloon was migrated into the second portion of the duodenum, suggesting that it might have obstructed the bile and pancreatic ducts, inducing cholangitis and pancreatitis. After the PEG-tube was replaced at the appropriate position, vomiting and abdominal tenderness improved dramatically and laboratory studies became normal immediately. Our case suggests that it is important to secure PEG-tube at the level of skin, especially after replacement.

- Citation: Imamura H, Konagaya T, Hashimoto T, Kasugai K. Acute pancreatitis and cholangitis: A complication caused by a migrated gastrostomy tube. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(39): 5285-5287

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i39/5285.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i39.5285

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) has gained broad acceptance as an effective method for achieving enteral access in patients who need chronic nutritional support. The feeding through PEG-tube is convenient, safe, and agreeable. Most of complications of PEG-tube feeding are minor, except for those arising at tube-exchange, which is necessary for a long-term feeding because of degradation of tubes, or incidental tube-removal. It is better to exchange PEG-tubes under fluoroscope in hospital for preventing complications. However, many primary doctors perform at the bed side in patient’s home through unavoidable circumstances. This is one of the reasons why serious complications occur when a long-term PEG-tube feeding is needed.

In this report, we describe a case of pancreatitis and cholangitis induced by dislocated PEG-tube, which are the very rare complications of PEG-tube feeding.

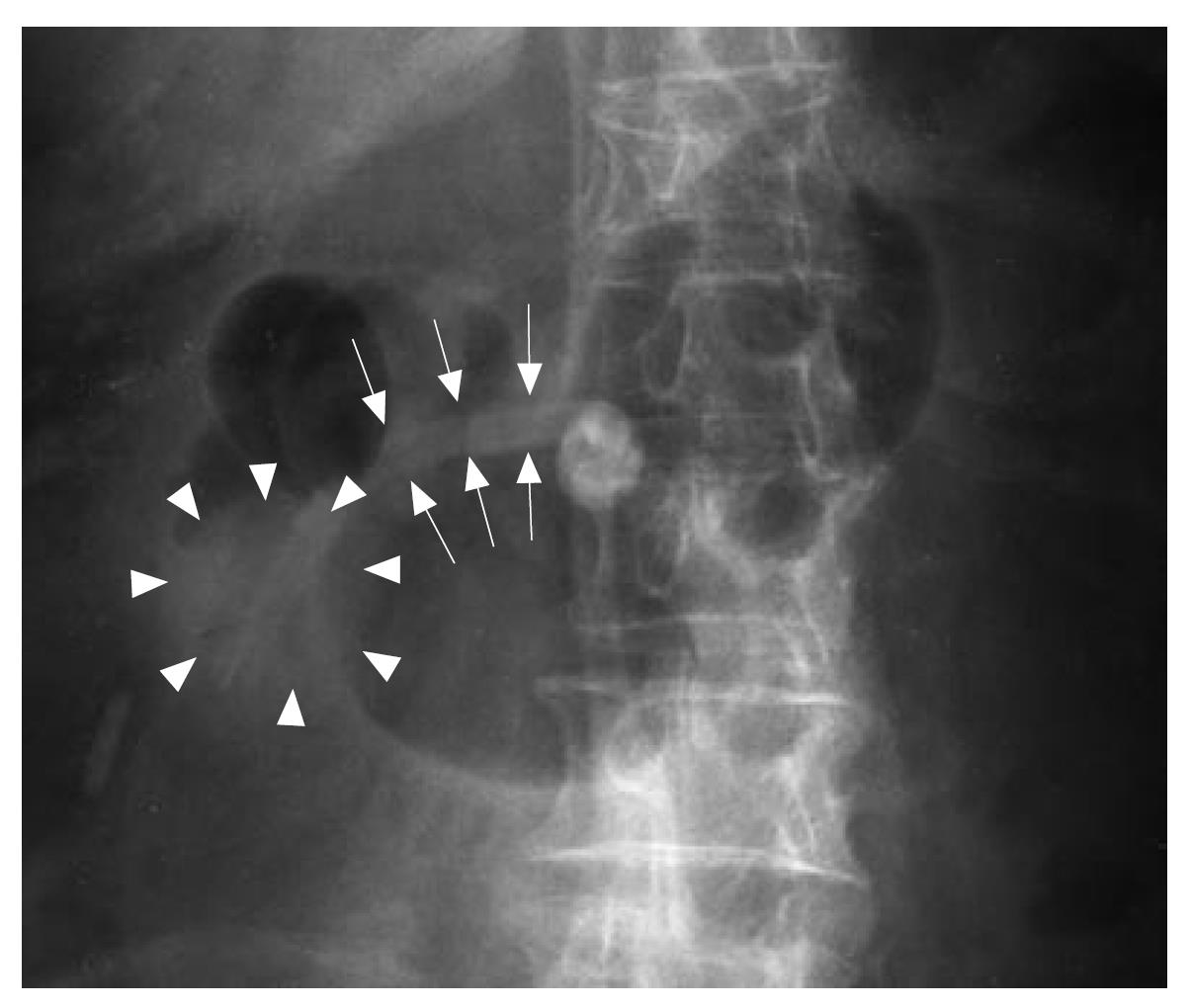

An 86-year-old Japanese woman with PEG-tube feeding was referred to our hospital for reiterated emesis. She had an attack of cerebral infarction and cerebral embolism at the age of 84 years. Since the disease caused her dysphagia and continuous consciousness disturbance, she received chronic nutritional support by PEG-tube feeding. One month before her hospitalization, a gastrostomy tube (Gastrostomy-tube, Bard Access Systems, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) with a diameter of 18 F, which is fixed by an intragastric balloon (20 mL of water) and an external disc bumper, was replaced by her family doctor in her home without radiologic confirmation, and she sometimes vomited gastric juice and bile without enteric nutrient. Her family noticed that the PEG-tube was sometimes drawn into the stomach. At her hospitalization, she complained of severe tenderness at the epigastric region and the PEG-tube was drawn into the stomach. The distance between the balloon and external disc bumper was 8 cm measured by a scale indicated on the PEG-tube. Laboratory studies revealed 10.4 × 109/L white blood cells (normal range: 5.0-8.0 × 109/L), 97.9 mg/L C-reactive protein (normal range: < 3 mg/L), 1.24 μmol/L total serum bilirubin (normal range: 0.49-2.16 μmol/L), 213 U/L aspartate aminotransferase (normal range: 10-34 U/L), 254 U/L alanine aminotransferase (normal range: 5-40 U/L), 553 U/L alkaline phosphatase (normal range: 100-358 U/L), 238 U/L lactate dehydrogenase (normal range: 104-224 U/L), 1191 U/L amylase (normal range: 32-112 U/L), 176 U/L gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase (normal range: 7-29 U/L). A diagnosis of acute pancreatitis and cholangitis was made based on the physical examination and laboratory findings. Abdominal roentgenography and computed tomography (CT) showed that the tip of PEG-tube with the inflated balloon was migrated into the second portion of the duodenum (Figures 1 and 2), suggesting that it might have disturbed the flow of bile and pancreatic juice at the papilla, and thus was thought to be the cause of cholangitis and pancreatitis. No stone or tumor was found at this region in these studies.

Once the balloon was deflated and fixed at the appropriate position by the balloon re-inflation after the tube was retracted into the stomach. After the PEG-tube was replaced at the appropriate position, vomiting and abdominal tenderness improved on the next day and laboratory studies became normal after two days.

PEG has become the preferred method in patients requiring long-term enteral nutrition because of its ease and safety of placement. Previous studies reported that complications are infrequent and a procedure-related mortality is less than 1%[1,2]. Common procedure-related complications include wound infection, aspiration, hemorrhage, pneumoperitoneum, peritonitis, and common long-term complications include leakage, granulation tissue, unintentional removal, buried bumper syndrome[3-7]. Obstructive pancreatitis and cholangitis induced by migrated PEG-tube are the very rare complications.

Although PEG-tube feeding is generally considered safe with a low rate of serious complications, dislocation of the PEG-tube into the duodenum can lead to symptoms of obstructive pancreatitis and cholangitis. Because a balloon with PEG-tube is hard to pass through the pyloric ring, a migrated balloon may obstruct the pyloric ring and cause vomiting. In this case, the family doctor might have inserted the PEG-tube too deep into the duodenum, so the tube passed through the pyloric ring and the balloon was inflated in the duodenum. As enteral peristalsis moved the balloon up to papilla of Vater, the flow of bile and pancreatic juice might have been obstructed. These speculations were supported by the frequent PEG-tube traction into the stomach noticed by her family, and her repeated vomiting due to small bowel obstruction by the balloon. Roentgenography could easily show the dislocation of PEG-tube which might have been noticed by checking carefully the length of PEG-tube over the skin.

Five cases of acute pancreatitis related to gastrostomy tube migration have been reported[8-12]. Foley catheter has been used as PEG-tubes in 4 cases[8-10,12]. This catheter is more likely to migrate because it has no external bumper which prevents dislocation of the tube. In another case using a gastrostomy tube with an external bumper, spontaneous loosening of the external bumper caused the tube migration[11]. In this case, a technical error might have caused tube dislocation when a new tube was replaced blindly, although the tube has an external bumper.

This case demonstrates that a malpositioned PEG-tube can be an iatrogenic cause of acute pancreatitis and cholangitis. It is important to secure PEG-tube at the level of skin, especially a couple of days after its replacement.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Li JL

| 1. | Park RH, Allison MC, Lang J, Spence E, Morris AJ, Danesh BJ, Russell RI, Mills PR. Randomised comparison of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and nasogastric tube feeding in patients with persisting neurological dysphagia. BMJ. 1992;304:1406-1409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wicks C, Gimson A, Vlavianos P, Lombard M, Panos M, Macmathuna P, Tudor M, Andrews K, Westaby D. Assessment of the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding tube as part of an integrated approach to enteral feeding. Gut. 1992;33:613-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kavic SM, Basson MD. Complications of endoscopy. Am J Surg. 2001;181:319-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | McClave SA, Chang WK. Complications of enteral access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:739-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Crosby J, Duerksen D. A retrospective survey of tube-related complications in patients receiving long-term home enteral nutrition. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1712-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hull MA, Rawlings J, Murray FE, Field J, McIntyre AS, Mahida YR, Hawkey CJ, Allison SP. Audit of outcome of long-term enteral nutrition by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Lancet. 1993;341:869-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kirchgatterer A, Bunte C, Aschl G, Fritz E, Hubner D, Kranewitter W, Fleischer M, Hinterreiter M, Stadler B, Knoflach P. Long-term outcome following placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in younger and older patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:271-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bui HD, Dang CV. Acute pancreatitis: a complication of Foley catheter gastrostomy. J Natl Med Assoc. 1986;78:779-781. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Panicek DM, Ewing DK, Gottlieb RH, Chew FS. Gastrostomy tube pancreatitis. Pediatr Radiol. 1988;18:416-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Barthel JS, Mangum D. Recurrent acute pancreatitis in pancreas divisum secondary to minor papilla obstruction from a gastrostomy feeding tube. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:638-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Duerksen DR. Acute pancreatitis caused by a prolapsing gastrostomy tube. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:792-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Miele VJ, Nigam A. Obstructive jaundice and pancreatitis secondary to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube migration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1802-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |