Published online Oct 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i39.5253

Revised: August 11, 2007

Accepted: September 12, 2007

Published online: October 21, 2007

AIM: To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of early nasogastric enteral nutrition (NGEN) for patients with severe acute pancreatitis (SAP).

METHODS: We searched Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 2, 2006), Pub-Medline (1966-2006), and references from relevant articles. We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) only, which reported the mortality of SAP patients at least. Two reviewers assessed the quality of each trial and collected data independently. The Cochrane Collaboration’s RevMan 4.2.9 software was used for statistical analysis.

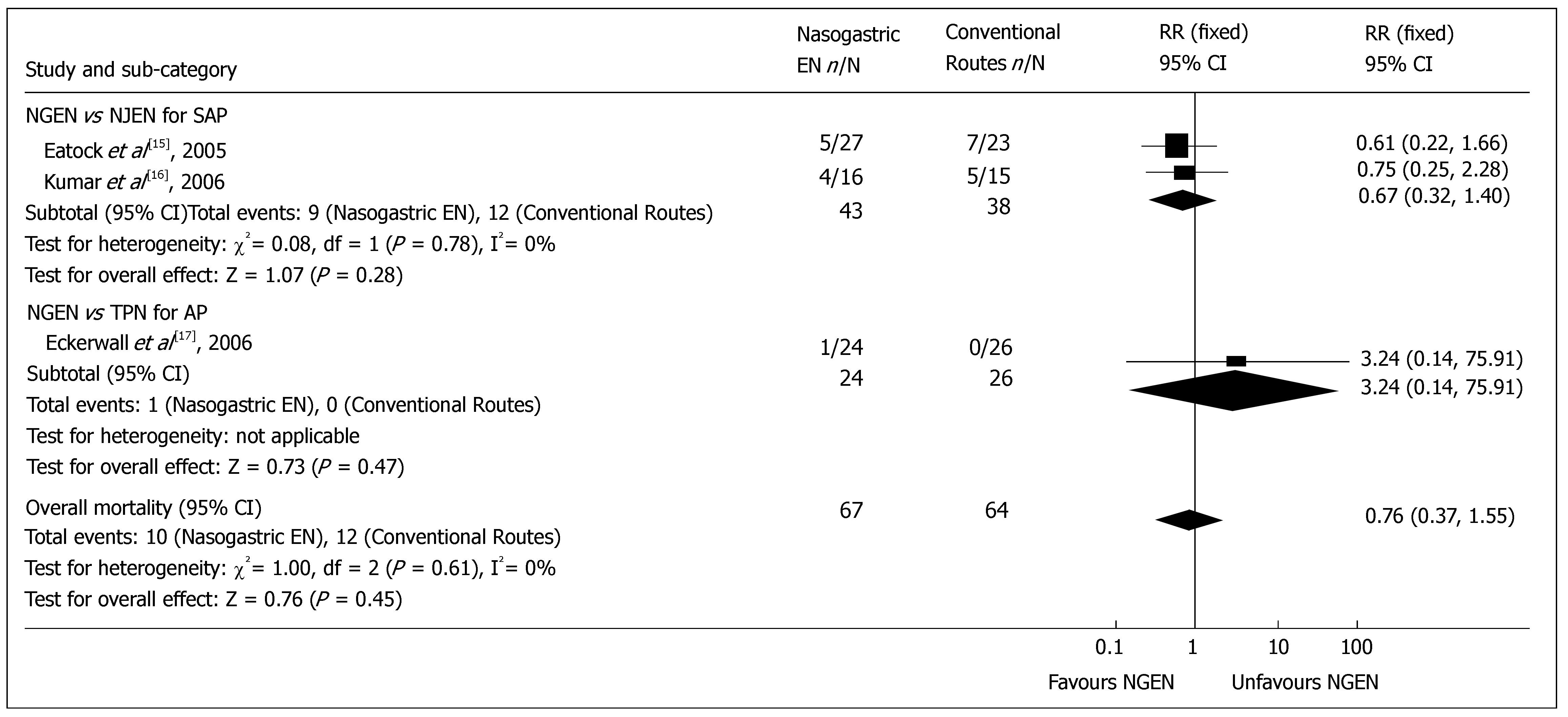

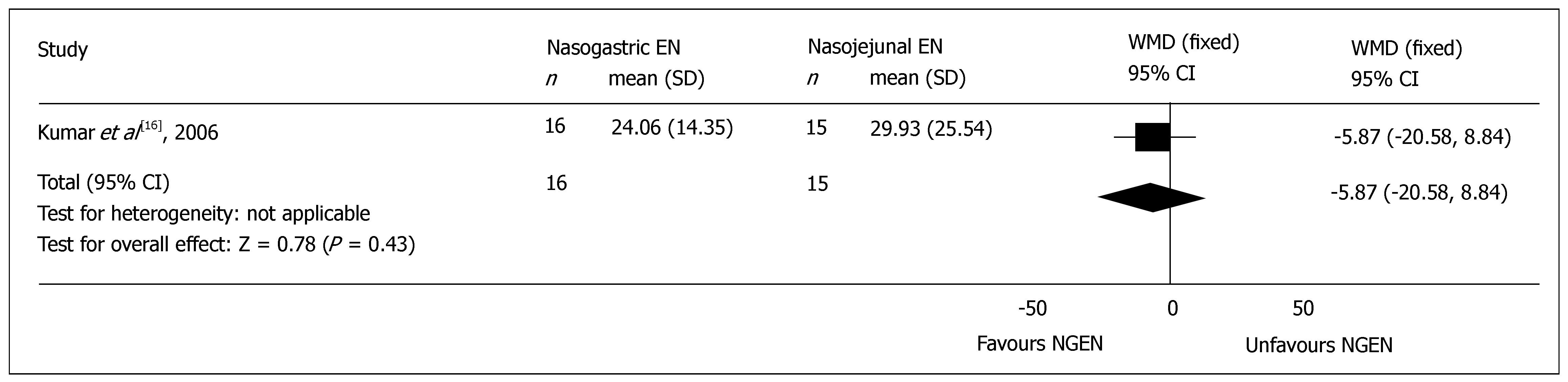

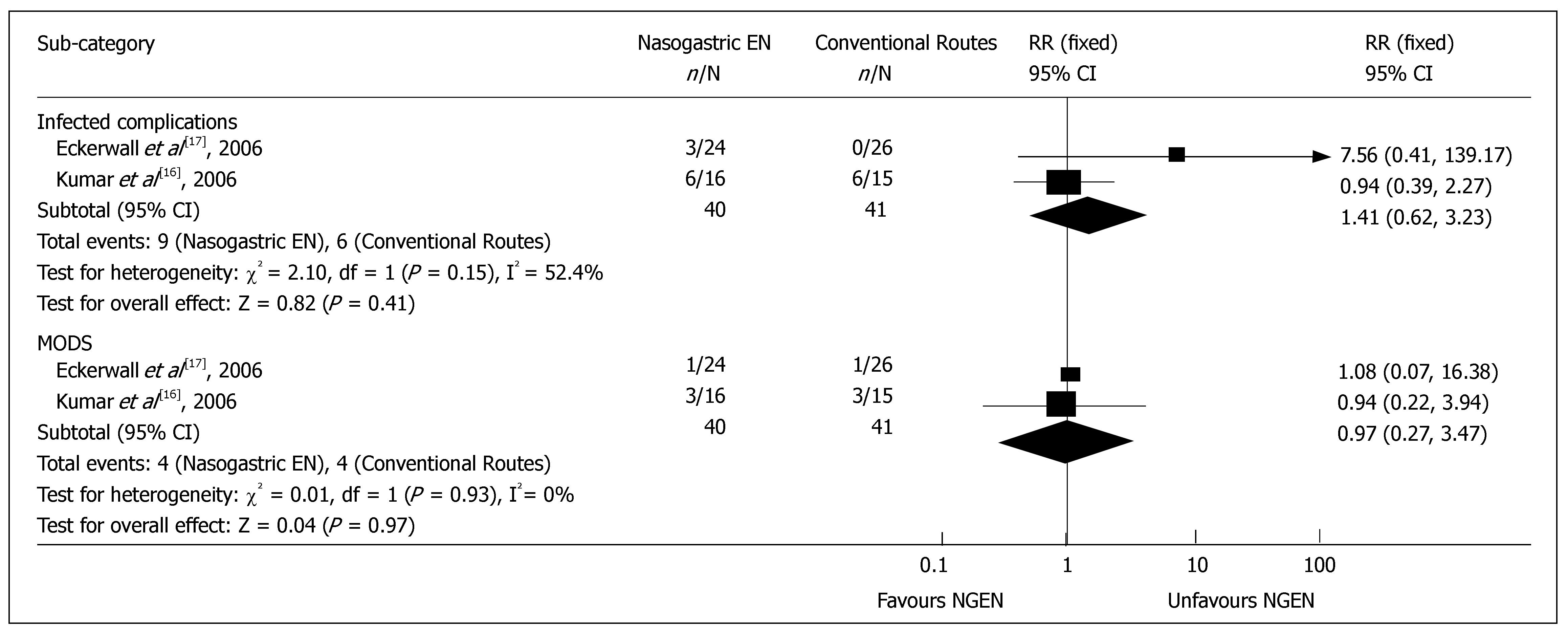

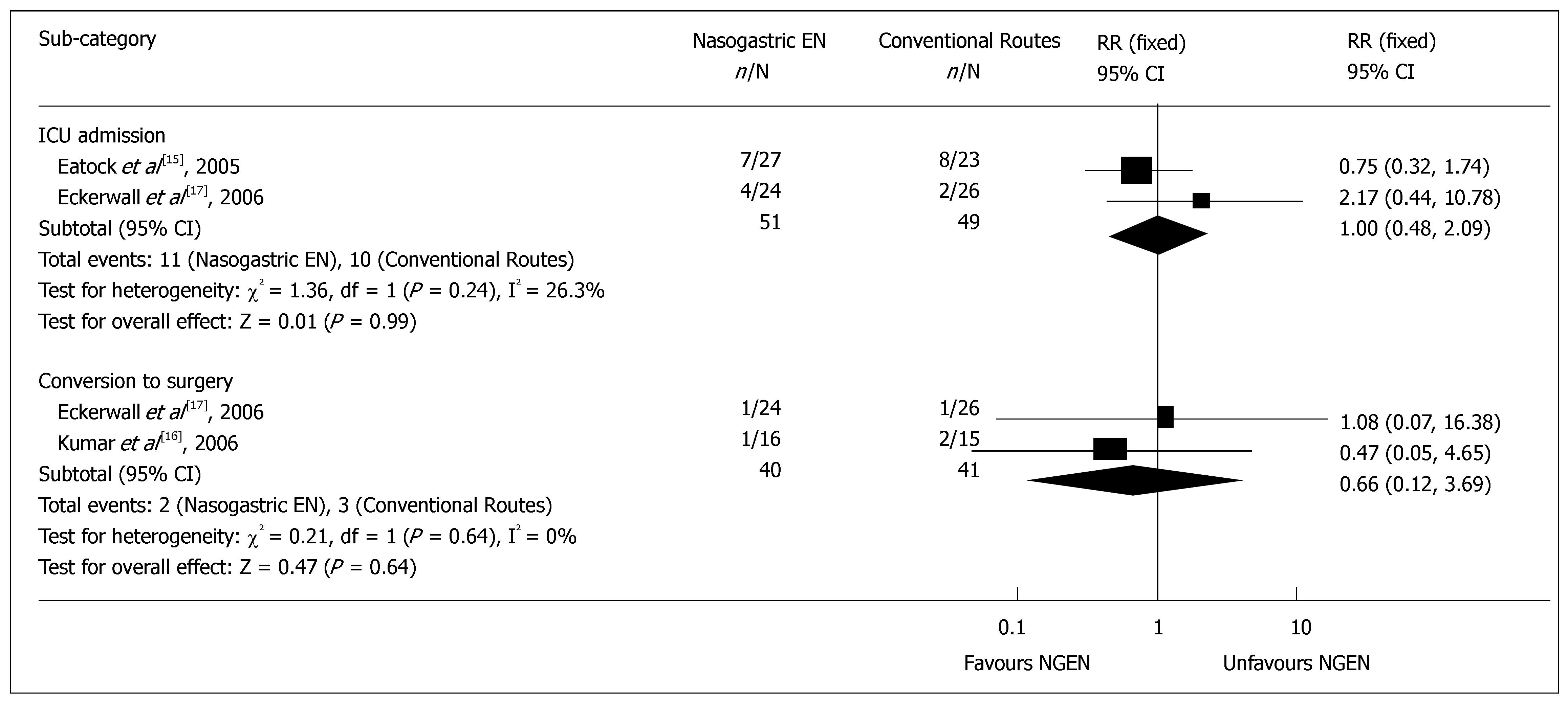

RESULTS: Three RCTs were included, involving 131 patients. The baselines of each trial were comparable. Meta-analysis showed no significant differences in mortality rate of SAP patients between nasogastric and conventional routes (RR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.37 and 1.55, P = 0.45), and in other outcomes, including time of hospital stay (weighted mean difference = -5.87, 95% CI = -20.58 and 8.84, P = 0.43), complication rate of infection (RR = 1.41, 95% CI = 0.62 and 3.23, P = 0.41) or multiple organ deficiency syndrome (RR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.27 and 3.47, P = 0.97), rate of admission to ICU (RR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.48 and 2.09, P = 0.99) or conversion to surgery (RR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.12 and 3.69, P = 0.64), as well as recurrence of re-feeding pain and adverse events associated with nutrition.

CONCLUSION: Early NGEN is a breakthrough in the management of SAP. Based on current studies, early NGEN appears effective and safe. Since the available evidence is poor in quantity, it is hard to make an accurate evaluation of the role of early NGEN in SAP. Before recommendation to clinical practice, further high qualified, large scale, randomized controlled trials are needed.

- Citation: Jiang K, Chen XZ, Xia Q, Tang WF, Wang L. Early nasogastric enteral nutrition for severe acute pancreatitis: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(39): 5253-5260

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i39/5253.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i39.5253

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is one of the most common pancreatic diseases, with an incidence rate of 4.9-80/100000 per year, and there was a trend to increase during the past two decades[1]. Around 80% of patients with mild acute pancreatitis (MAP) are treatable with a short period of bowel rest, simple intravenous hydration, and analgesia[1,2]. However, severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is complicated by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), leading to hypermetabolism and high protein catabolism[3]. Consequently, nutritional stores are rapidly consumed and about 30% of patients with SAP undergo malnutrition[3,4]. Acute malnutrition is expected to increase morbidity and mortality due to impaired immune function, increased risk of sepsis, poor wound healing, and multiple organ failure[3]. Thus, current therapy for AP has shifted to intensive medical care, nutrition support, infection control and medicine administration, while early invasive intervention as surgery has been reserved for defined clinical indication[5,6]. Nutritional management for AP is an important issue and regarded as an indispensable approach.

Oral or enteral feeding may be harmful in AP and is thought to stimulate exocrine pancreatic secretion and consequently autodigestive process[4]. Up to the mid 1990s, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and gastrointestinal tract rest have been comprehensively recommended in the acute phase of pancreatitis, which make pancreas at rest to reduce pancreatic exocrine secretion and also meet nutritional need[6,7]. Intestinal mucosa atrophies during fasting as TPN phase, which would induce bacteria translocation in gastrointestinal tract and cause pancreatic necrotic tissue infection[8]. Animal experiments and several human studies have shown that enteral nutrition (EN) is safe and can preserve the integrity of intestinal mucosa to decrease the incidence of infectious complications and other severe complications, such as multiple organ deficiency syndrome (MODS)[8-10]. Furthermore, EN does not stimulate pancreatic exocrine secretion, if the feeding tube is positioned in the jejunum by nasojejunal or jejunostomy routes[8,11]. Therefore, TPN or jejunal EN is considered the mainstream of nutritional support for AP.

Recently, some researchers have considered the feasibility of EN through nasogastric (NG) tube to improve the nutrition status of patients with AP in the early phase[7,12]. However, this breakthrough is potentially opposing to the requirement of pancreatic rest in the acute inflammation phase. The present study was to confirm whether nasogastric EN is safe and effective for patients with AP.

We searched electronic databases of Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 2, 2006), Pub-Medline (1966-2006), and references from relevant articles. The search strategy used was "Enteral Nutrition" (MeSH) AND ["Pancreatitis" (MeSH) OR "Pancreatitis, Acute Necrotizing" (MeSH)], with limitations to Randomized Controlled Trial, Humans. There was no limitation of publication language. This systematic review will be updated if more randomized controlled trials (RCTs) can be found through the monthly automatic search procedure from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at the National Library of Medicine.

Only randomized controlled trials were eligible. Eligible patients include those who diagnosed as acute pancreatitis by Atlanta classification, and those with severe diseases assessed by APACHE II criteria, and/or Ranson criteria, and/or Balthazar computer tomography criteria. Any etiology was eligible, and there was no limitation of age, race, and sex distribution. Comparator intervention was considered an early enteral nutritional route through nasogastric tube (NGEN), while control intervention was considered one of the conventional pancreatic-rest nutritional support routes, such as total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or enteral nutrition by nasojejunal tube (NJEN) or jejunostomy tube (JSEN). Additionally, other combined treatments included gastrointestinal decompression, prophylactic antibiotics, fluid management, artificial ventilation or renal replacement therapy for MODS, endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography with endoscopic sphincterotomy for selected biliary patients, and surgery for indicated patients. The primary outcome measure of effectiveness was overall mortality, the secondary outcome measures of effectiveness was hospital stay, complications and their management, while the outcome measures of safety included re-feeding pain recurrence and adverse events related to nasogastric enteral nutrition.

To evaluate the methodological quality of included studies, two reviewers (Jiang K and Chen XZ) assessed the quality of methods used in studies independently. According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review 4.2.6[13], we assessed the quality of RCTs using random allocation concealment as adequate (A), unclear (B), inadequate (C), or not used (D); blinding process as double blind (A), single blind (B), unclear (C) or not used (D); intention-to-treat (ITT) as yes (A), unclear (B), or not used (C), or loss, withdrawal, dropout, cross-intervention not reported (D). The criteria proposed by Jadad et al[14] were also used to evaluate the quality of trials.

Data were collected by the two reviewers independently, including study sample (number of each arm), interventions (nutrition management, approach and regimens) and outcomes (overall mortality, time of hospital stay, complications of systematic or local infection, or MODS defined as failure in no less than 2 organs, re-feeding pain defined as pain requiring discontinuation of feeding, elevated serum amylase levels at least two-fold higher than normal[7], and adverse events related to nutrition), as well as the publication year and country of studies, and the number of withdrawals and dropouts and the reasons.

Any disagreement in quality assessment and data collection was discussed and solved by a third reviewer as the referee.

Meta-analysis was performed with the Cochrane Collaboration’s RevMan 4.2.9 software. All P-values were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For dichotomous variables, the risk ratio (RR) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI); for continuous variables, weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals. Heterogeneity was determined by chi-square test. If any heterogeneity existed, the following techniques were employed to explain it: (1) random effect model, (2) sub-group analysis including different control arms as TPN or EN through nasojejunal or jejunostomy tube, (3) sensitivity analysis performed by excluding the trials which potentially biased the results. Any patients randomly assigned in each trial, but not analyzed in the present meta-analysis, were calculated.

Three RCTs[15-17] were eligible for the inclusion criteria, and 131 participants were included. Of them, 67 were randomly assigned to NGEN group and 64 to conventional nutritional route group. Conventional routes included TPN and NJEN, but not JSEN. The mean number of samples for each trial was 43.7 (31-50). The baselines of each trial were comparable. The details of included trials are listed in Table 1, and the results of quality assessment in Table 2.

| Reference | Yr | Country | Number of intervention/control | Inclusion/exclusion criteria of participants | Drop-out/withdrawal | |

| [15] | 2005 | Scotland | 27 (NGEN)/23 (NJEN) | Inclusion: both a clinical and biochemical presentation of AP (abdominal pain and serum amylase at least 3 times the upper limit of the reference range), and objective evidence of disease of disease severity (Glasgow prognostic score ≥ 3, or APACHE II ≥ 6, or CRP > 150 mg/L). | One excluded in NJEN group for misdiagnosed and 2 in NJEN group received NGEN for failure of NJ tube placement. | |

| Exclusion: patients under 18 yr of age and pregnant females. | ||||||

| Inclusion: severity was defined according to the Atlanta criteria (ie, presence of organ failure and APACHE score of ≥ 8 or CT severity score ≥ 7). | ||||||

| [16] | 2006 | India | 16 (NGEN)/15 (NJEN) | Exclusion: if there was a delay of more than 4 wk between the onset of symptoms and presentation to the hospital, if they were already taking oral feeding at presentation, if there was acute exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis, or if they were in shock (ie, systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg at the time of randomization). | One excluded in NJEN group for failure of NJ tube placement. | |

| [17] | 2006 | Sweden | 24 (NGEN)/26 (TPN) | Inclusion: abdominal pain, amylase ≥ 3 times upper limit of normal, onset of abdominal pain within 48 h, APACHE II score ≥ 8 and/or CRP ≥ 150 mg/L and/or peripancreatic liquid shown on CT. | One patient from each group was considered as protocol violators due to surgery performed after study inclusion on d 2 in 1 case, and a dislocated tube not accepted to be replaced in the other one | |

| Exclusion: AP due to surgery, inflammatory bowel disease, stoma, short bowel, chronic pancreatitis with exacerbation, and patients under 18 yr of age. |

Overall mortality: Three included RCTs reported the mortality. The overall mortality rate of early NGEN group and conventional route group was 14.9% (10/67) and 18.8% (12/64) respectively, which is consistent with the reported rate[18]. No heterogeneity was detected (P = 0.61). Meta-analysis showed no significant difference in overall mortality between early NGEN and conventional route groups (RR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.37 and 1.55, P = 0.45) (Figure 1). Sub-group analysis showed no significant difference in overall mortality between NGEN and NJEN groups[15,16] (RR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.32 and 1.40, P = 0.28), as well as between NGEN and TPN groups[17] (RR = 3.24, 95% CI = 0.14 and 75.91, P = 0.47).

Hospital stay: All the included RCTs reported the mean time of total hospital stay, but 2 trials did not mentioned the standard difference (SD)[15,17], and were excluded from the meta-analysis. There was no significant difference in the mean time of total hospital stay between NGEN and NJEN groups (WMD = -5.87, 95% CI = -20.58 and 8.84, P = 0.43) (Figure 2). The weighted mean time of hospital stay of patients in early NGEN and conventional route groups was 15.4 d and 15.3 d, respectively.

Complications and management: Two RCTs reported the detailed data on infective complications or MODS[16,17]. The results of meta-analysis showed no significant difference in infective complications, such as sepsis and infected pancreatic necrosis (RR = 1.41, 95% CI = 0.62 and 3.23, P = 0.41) (Figure 3), as well as in heterogeneity (P = 0.15). There was no significant difference in MODS (RR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.27 and 3.47, P = 0.97) (Figure 3), as well as in heterogeneity (P = 0.93). The rate for admission to intensive care unit was reported in 2 RCTs[15,17], which was 21.6% (11/51) and 20.4% (10/49) in early NGEN and conventional groups respectively (RR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.48 and 2.09, P = 0.99) (Figure 4). Two trials[16,17] reported that the rate for surgery was 5.0% (2/40) and 7.3% (3/41) in early NGEN and conventional route groups, respectively with no significant difference between the two groups (RR = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.12 and 3.69, P = 0.64) (Figure 4).

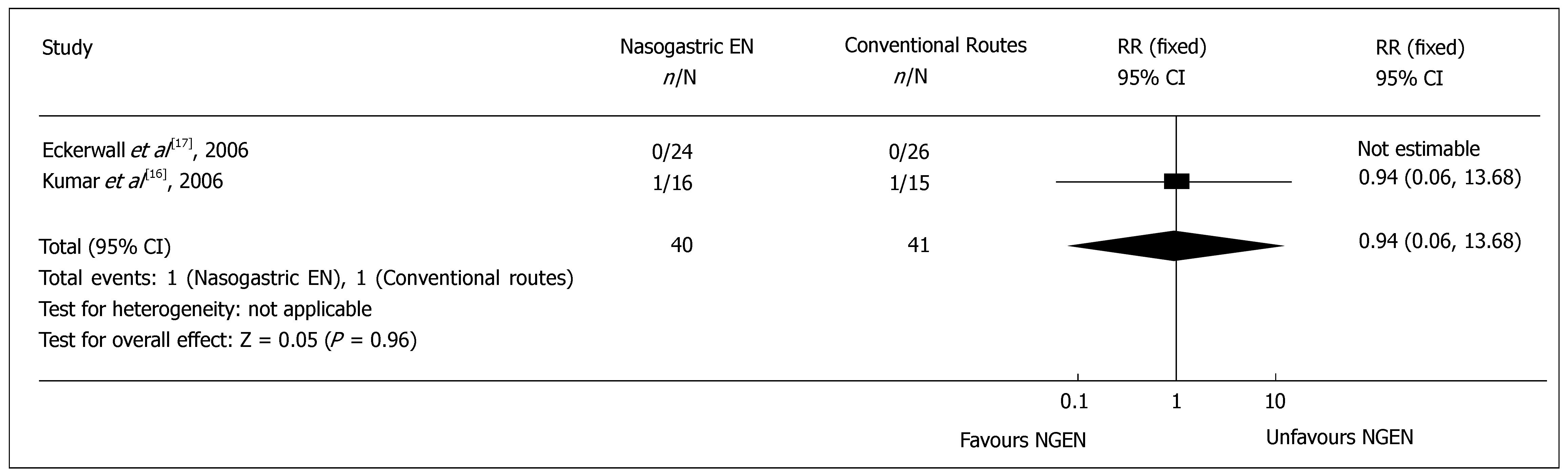

Re-feeding pain recurrence: Two RCTs[16,17] reported the cases needing to withdraw oral feeding due to recurrent re-feeding pain. Meta-analysis showed no significant difference in the recurrent re-feeding pain (RR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.06 and 13.68, P = 0.96) (Figure 5). The pain recurrence rate was 2.5% (1/40) and 2.4% (1/41) in NGEN and conventional route groups, respectively.

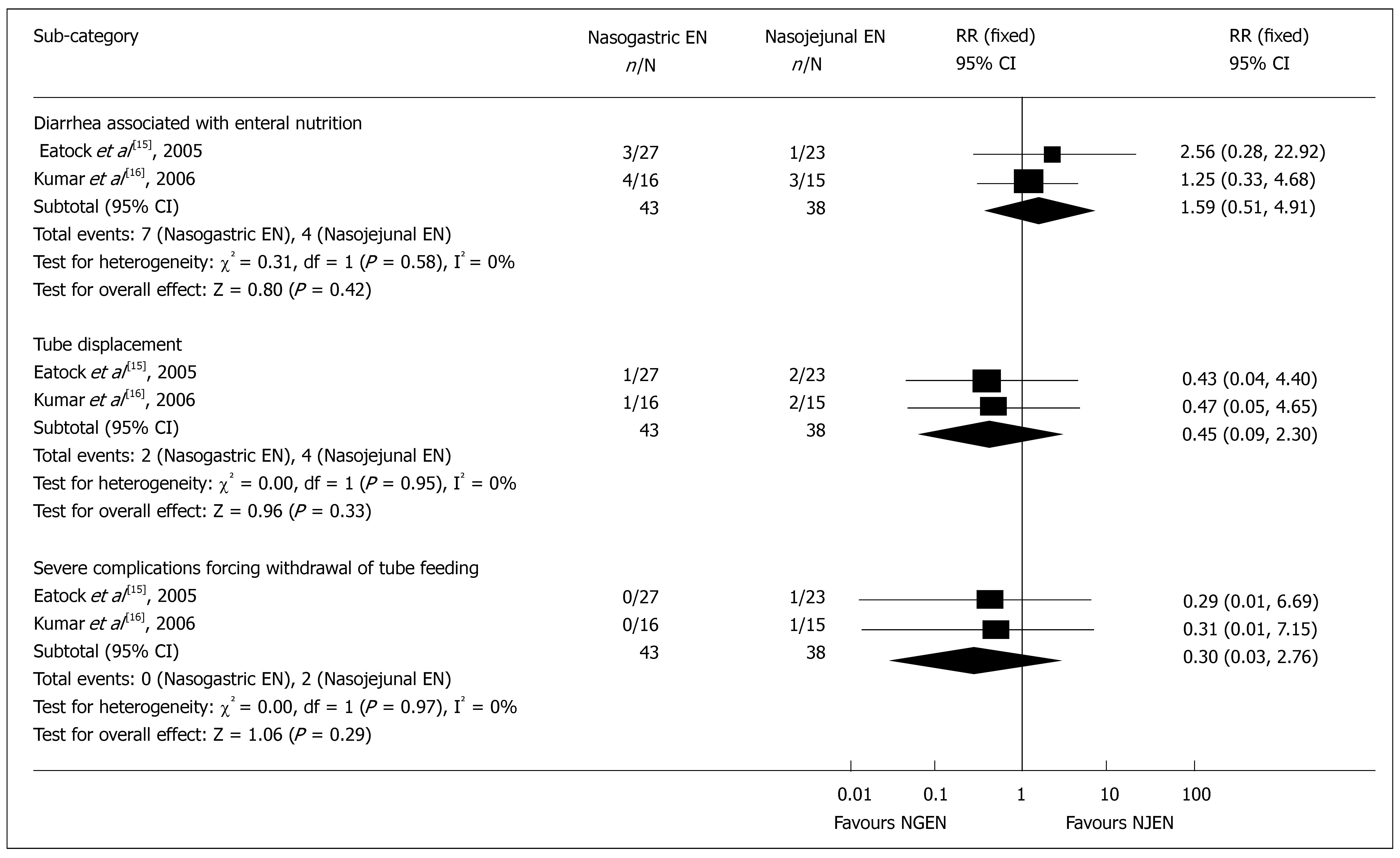

Adverse events associated with nutrition: Meta-analysis showed that the main adverse events associated with nutrition support were diarrhea (RR = 1.59, 95% CI = 0.51 and 4.91, P = 0.42), tube displacement (RR = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.09 and 2.30, P = 0.33), and withdrawal of feeding due to severe complications (RR = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.03 and 2.76, P = 0.29) (Figure 6). Other nutrition-associated complications were found in patients of the NJEN group who suffered from cardiorespiratory arrest at the moment of endoscopic tube placement which were successfully resuscitated[14] and in patients of the NJEN group with sweating and palpitation[15].

The present systematic review was intended to find the feasibility and safety of early nasogastric enteral nutrition in the management of severe acute pancreatitis. We selected 3 randomized controlled trials involving comparison between early NGEN and NJEN or TPN. The total number of samples was limited. All the trials did not perform a blinding process due to the nature of interventions. Two trials reported detailed randomization assignment methods[15,16], and two were put into practice based on allocation concealment and intention-to-treat method[15,17]. Sensitivity analysis showed negative results. Potential biases of the present systematic review included selection bias due to the severity criteria of one trial (Eatock 2005)[15] set at APACHE II > 6, on an international symposium[19]. Moreover, another concern is the high mortality (24.5%) in patients with the severity of the illness[20].

Treatment of SAP has been evolving from routine early aggressive surgical management towards conservative care for patients without evidence of pancreatic infection[21,22]. However, SAP remains a disease with a poor prognosis[23]. Artificial nutrition can prevent and provide a long term nutritional support for SAP[24]. Enteral nutrition is preferred to parenteral nutrition for improving patient outcomes[25,26], and has largely replaced the parenteral route[27]. However, early nasogastric enteral nutrition is regarded as a potentially pancreatic-unrest nutritional support route, which is harmful to the early acute phase of AP[15]. Eatock et al[12] first introduced the early nasogastric feeding into nutritional management of SAP, and then Pandey et al[7] applied oral re-feeding in patients with SAP, suggesting that the nasogastric feeding is feasible in up to 80% cases[15].

The present meta-analysis showed that early NGEN would be as effective and safe as early NJEN or TPN in SAP patients, without increase in mortality. Pancreatic infection, sepsis, and MODS are the complications of SAP[28]. Duration of organ failure during the first week of predicted severe acute pancreatitis is strongly associated with the risk of death or local complications[29]. Besides, NGEN did not increase severe complications and prolong hospital stay. Bacterial infection is the common complication of acute pancreatitis, and bacterial translocation from the gut is probably the first step in the pathogenesis of these infections[30]. NGEN could preserve the intestinal permeability including duodenum, proved by the assessment of excretion of polyethylene glycol and antiendotoxin core antibody IgM levels[17], which would be the best barrier for prevention of certain complications. Interleukin-6 serum levels are elevated very early in patients with necrosis infection[31], and C-reactive protein (CRP) is considered a valuable independent predictor of mortality[32]. IL-6 and CRP levels play a similar role in the control of systematic inflammatory response of early NGEN and TPN groups at each time point[17]. Moreover, biochemical nutritional parameters, such as serum albumin and prealbumin concentration in early NGEN and NJEN groups, are both well preserved without any significant difference[16].

After three-month follow-up, about 92% patients in the early NGEN group have no symptoms related to SAP, compared with 82% patients in the TPN group, but all pseudocysts occur in the early NGEN group[17], suggesting that early nasogastric enteral nutrition is potentially feasible in SAP patients. The clinical outcomes are quite similar to conventional routes, such as early nasojejunal or total parenteral nutrition. However, the incidence of late complications such as pseudocysts is likely higher in early nasogastric enteral nutrition group.

Enteral nutrition has no benefit to the mild acute pancreatitis subset[24]. However, oral re-feeding is feasible, but the proper time of commence needs to be further investigated. Oral re-feeding given 1 wk after onset of the disease is safe in selected MAP patients[4], while there is no evidence that early oral re-feeding within 1 wk is a feasible management for SAP.

In conclusion, early nasogastric enteral nutritional support route is potentially feasible and safe, which does not increase the rate of mortality, complication and re-feeding pain recurrence in patients with severe acute pancreatitis, and prolong the hospital stay. No major innovations in the treatment of SAP have been introduced in recent years[23]. It is a breakthrough in enteral nutrition management of severe acute pancreatitis, with a bright future because it is more convenient and cheaper. However, before it is applied in clinical practice, further investigation is necessary to validate its effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness.

The authors thank Professor Qing Xia, Department of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, China, for academic instructions, and Dr. Xin-Zu Chen, Department of General Surgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, Sichuan Province, China, for substantial methodological support.

Nutritional management of severe acute pancreatitis is an important issue and regarded as an indispensable approach. Total parenteral nutrition and gastrointestinal tract rest have been recommended in the management of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) sine the mid 1990s. Enteral nutrition through jejunal route has been accepted as a safe and effective approach to the management of SAP by preserving the integrity of intestinal mucosa and preventing bacterial translocation. Moreover, some studies have attempted to find the feasibility and safety of early enteral nutrition through nasogastric route.

Gastrointestinal and pancreatic rest has been regarded as an important factor for management of severe acute pancreatitis. Nevertheless, nasogastric enteral nutrition disobeys this discipline. Whether nasogastric route is able to gain the similar results needs to be further investigated. If possible, serological, radiological or histological appraisal should be considered for the effectiveness and safety of early nasogastric enteral nutrition in the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis.

Early nasogastric enteral nutrition is a breakthrough in the management of severe acute pancreatitis. Previously, it was forbidden for the sake of potentially opposing to the requirement of pancreatic rest in the acute inflammation phase. However, the present systematic review of three randomized controlled trials showed that nasogastric route does not worsen the clinical outcomes compared with the conventional total parenteral or jejunal enteral routes.

Nasogastric route is much more convenient in clinical practice. Moreover, it is obviously cheaper than nasojejunal tube placement. Based on the present results, nasogastric enteral nutrition can be applied in the early management of severe acute pancratitis. However, before its application in clinical practice, further investigation is necessary to validate its effectiveness and safety.

Severe acute panceatitis (SAP) is usually accompanied with pancreatic necrosis, systematic inflammatory response syndrome, or organ failure. Total partenteral nutrition (TPN) is the way to give nutrient substances intravenously, bypassing the digestive system. Nasogastric enteral nutrition (NGEN) is the way to provide nutrient substances for patients through a tube placed in the nose up to the stomach. Nasojejunal enteral nutrition (NJEN) is the way similar to NGEN, but the tube is placed up to the jejunum.

The authors evaluated the effectiveness and safety of early nasogastric enteral nutrition (NGEN) for severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) compared with conventional nutritional routes. Based on the current studies, early NGEN appears effective and safe, but the available evidence is limited.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Yin DH

| 1. | Jiang K, Chen XZ, Xia Q, Tang WF, Wang L. Early veno-venous hemofiltration for severe acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Zhongguo Xunzheng Yixue Zazhi. 2007;7:121-134. |

| 2. | McClave SA, Greene LM, Snider HL, Makk LJ, Cheadle WG, Owens NA, Dukes LG, Goldsmith LJ. Comparison of the safety of early enteral vs parenteral nutrition in mild acute pancreatitis. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1997;21:14-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Abou-Assi S, O'Keefe SJ. Nutrition in acute pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:203-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Meier R, Beglinger C, Layer P, Gullo L, Keim V, Laugier R, Friess H, Schweitzer M, Macfie J. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in acute pancreatitis. European Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. Clin Nutr. 2002;21:173-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Banks PA. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:377-386. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Tesinsky P. Nutritional care of pancreatitis and its complications. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 1999;2:395-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pandey SK, Ahuja V, Joshi YK, Sharma MP. A randomized trial of oral refeeding compared with jejunal tube refeeding in acute pancreatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23:53-55. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Heinrich S, Schäfer M, Rousson V, Clavien PA. Evidence-based treatment of acute pancreatitis: a look at established paradigms. Ann Surg. 2006;243:154-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Alscher KT, Phang PT, McDonald TE, Walley KR. Enteral feeding decreases gut apoptosis, permeability, and lung inflammation during murine endotoxemia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G569-G576. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hadfield RJ, Sinclair DG, Houldsworth PE, Evans TW. Effects of enteral and parenteral nutrition on gut mucosal permeability in the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1545-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vu MK, van der Veek PP, Frölich M, Souverijn JH, Biemond I, Lamers CB, Masclee AA. Does jejunal feeding activate exocrine pancreatic secretion? Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:1053-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Eatock FC, Brombacher GD, Steven A, Imrie CW, McKay CJ, Carter R. Nasogastric feeding in severe acute pancreatitis may be practical and safe. Int J Pancreatol. 2000;28:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6 updated September 2006. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 79-84. |

| 14. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12275] [Cited by in RCA: 12887] [Article Influence: 444.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Eatock FC, Chong P, Menezes N, Murray L, McKay CJ, Carter CR, Imrie CW. A randomized study of early nasogastric versus nasojejunal feeding in severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:432-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kumar A, Singh N, Prakash S, Saraya A, Joshi YK. Early enteral nutrition in severe acute pancreatitis: a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing nasojejunal and nasogastric routes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:431-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Eckerwall GE, Axelsson JB, Andersson RG. Early nasogastric feeding in predicted severe acute pancreatitis: A clinical, randomized study. Ann Surg. 2006;244:959-965; discussion 965-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Carnovale A, Rabitti PG, Manes G, Esposito P, Pacelli L, Uomo G. Mortality in acute pancreatitis: is it an early or a late event? JOP. 2005;6:438-444. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Bradley EL. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1929] [Cited by in RCA: 1735] [Article Influence: 54.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Krenitsky J, Parrish C. University of Virginia Nutrition E-Journal Club, April 2005. 4-28. Available from: http: //www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/dietitian/dh/journal/april2005.cfm.. |

| 21. | Malangoni MA, Martin AS. Outcome of severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2005;189:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yousaf M, McCallion K, Diamond T. Management of severe acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2003;90:407-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Goldacre MJ, Roberts SE. Hospital admission for acute pancreatitis in an English population, 1963-98: database study of incidence and mortality. BMJ. 2004;328:1466-1469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Working Party of the British Society of Gastroenterology, Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland, Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Association of Upper GI Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 3:iii1-iii9. |

| 25. | Carroll JK, Herrick B, Gipson T, Lee SP. Acute pancreatitis: diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:1513-1520. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Marik PE, Zaloga GP. Meta-analysis of parenteral nutrition versus enteral nutrition in patients with acute pancreatitis. BMJ. 2004;328:1407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mitchell RM, Byrne MF, Baillie J. Pancreatitis. Lancet. 2003;361:1447-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rau BM, Kemppainen EA, Gumbs AA, Büchler MW, Wegscheider K, Bassi C, Puolakkainen PA, Beger HG. Early assessment of pancreatic infections and overall prognosis in severe acute pancreatitis by procalcitonin (PCT): a prospective international multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2007;245:745-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Johnson CD, Abu-Hilal M. Persistent organ failure during the first week as a marker of fatal outcome in acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2004;53:1340-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 436] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | de Madaria E, Martínez J, Lozano B, Sempere L, Benlloch S, Such J, Uceda F, Francés R, Pérez-Mateo M. Detection and identification of bacterial DNA in serum from patients with acute pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54:1293-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Riché FC, Cholley BP, Laisné MJ, Vicaut E, Panis YH, Lajeunie EJ, Boudiaf M, Valleur PD. Inflammatory cytokines, C reactive protein, and procalcitonin as early predictors of necrosis infection in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Surgery. 2003;133:257-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mäkelä JT, Eila H, Kiviniemi H, Laurila J, Laitinen S. Computed tomography severity index and C-reactive protein values predicting mortality in emergency and intensive care units for patients with severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2007;194:30-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |