Published online Oct 21, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i39.5238

Revised: August 8, 2007

Accepted: September 24, 2007

Published online: October 21, 2007

AIM: To evaluate the safety and efficacy of a long-term therapy with infliximab in Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) patients retrospectively.

METHODS: The medical charts of 50 patients (40 CD and 10 UC), who received after a loading dose of 3 infliximab infusions scheduled re-treatments every 8 wk as a maintenance protocol, were reviewed.

RESULTS: Median (range) duration of treatment was 27 (4-64) mo in CD patients and 24.5 (6-46) mo in UC patients. Overall, 32 (80%) CD and 9 (90%) UC patients showed a sustained clinical response or remission throughout the maintenance period. Three CD patients shortened the interval between infusions. Eight (20%) CD patients and 1 UC patient underwent surgery for flare up of disease. Nine out of 29 CD and 4 out of 9 UC patients, who discontinued infliximab scheduled treatment, are still relapse-free after a median of 16 (5-30) and 6.5 (4-16) mo following the last infusion, respectively. Ten CD patients (25%) and 1 UC patient required concomitant steroid therapy during maintenance period, compared to 30 (75%) and 9 (90%) patients at enrolment. Of the 50 patients, 16 (32%) experienced at least 1 adverse event and 3 patients (6%) were diagnosed with cancer during maintenance treatment.

CONCLUSION: Scheduled infliximab strategy is effective in maintaining long-term clinical remission both in CD and UC and determines a marked steroid sparing effect. Long-lasting remission was observed following infliximab withdrawal.

- Citation: Caviglia R, Ribolsi M, Rizzi M, Emerenziani S, Annunziata ML, Cicala M. Maintenance of remission with infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: Efficacy and safety long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(39): 5238-5244

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i39/5238.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i39.5238

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic-relapsing diseases the clinical course of which is characterized by periods of remission and periods of acute flare up. The clinical symptoms have a strong impact on the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[1-3]. Although many drugs have been used in the treatment of IBD, none has, so far, been shown to modify the natural history of the diseases or to maintain a stable remission over time[4,5]. For many years, corticosteroids have represented the cornerstone of therapy for induction of remission in IBD, having demonstrated efficacy in inducing a rapid clinical response, in CD as well as in UC; however, long-lasting remission was not achieved and the side-effects emerging with long-term use exceeded the clinical benefits[6]. Immunomodulators have been demonstrated to be efficacious as adjunctive therapy and as steroid-sparing agents; but their slow onset of action precludes their use in the active clinical setting as a sole therapy[7].

The introduction of biological agents in the therapeutic armamentarium for CD and UC has significantly changed the treatment strategies and clinical outcomes. Infliximab (IFX) is a chimeric monoclonal IgG1 antibody directed against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) able to almost completely neutralize its biological activity[8]. Several placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of IFX treatment in active luminal and fistulizing CD[9-13]. Recently, IFX has become an alternative choice also in the treatment of UC. Indeed, following the conflicting conclusions of 2 placebo-controlled studies performed in patients with moderately severe steroid-resistant UC[14,15], showing opposite clinical effects, another two randomized controlled trials have since then been published, demonstrating the clinical efficacy of IFX therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe UC[16,17].

Some safety issues are associated with IFX use, mostly related to the development of adverse events (e.g., opportunistic infections, autoimmune disorders, and infusion reactions)[18-20]. Major concerns are related to the reactivation of latent tuberculosis and development of malignancy, even if there is no clear evidence that the use of IFX increases the incidence of solid cancers[21,22]. Although the efficacy of a therapeutic strategy consisting of a loading dose of 3 IFX infusions (5 mg/kg) at 0, 2, and 6 wk and, thereafter, every 8 wk is supported by several placebo-controlled studies, very few data are available on the use of IFX for > 12 mo or > 8 doses, either in active CD or in active UC[23,24].

The aim of the present single-centre study was to retrospectively analyze the prospectively collected data on the safety and efficacy of long-term therapy with IFX in CD and UC patients treated with a scheduled regimen.

The medical charts of 79 patients affected by IBD (59 CD and 20 UC patients, mean age 47.7 years) and treated with IFX (Remicade; Centocor Inc., Malvern, PA, USA) between January 1999 and September 2005 at the Department of Digestive Diseases of the Campus Bio-Medico University Hospital were retrospectively reviewed (Table 1).Diagnosis of IBD was based on the standard combination of clinical, endoscopic, histological, and radiological criteria. Patients were classified into one of 3 groups of treatment, according to IFX infusion administration: (1) episodic therapy only in 10 patients (5 CD, 5 UC), (2) episodic followed by on-demand maintenance in 19 patients (14 CD, 5 UC), and (3) induction therapy followed by scheduled maintenance therapy every 8 wk in 50 patients (40 CD, 10 UC).

| Clinical characteristics | IBD (CD + UC) | Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis |

| n | 50 | 40 | 10 |

| Gender (M/F) | 23/27 | 18/22 | 4/6 |

| Age (yr)1 | 47.7 ± 15.6 | 45.4 ± 17.9 | 52.7 ± 8.9 |

| Median disease duration (yr) | 10.8 | 9.2 | 9.3 |

| (range) | (0.3-22.2) | (0.3-22.2) | (2.1-15.1) |

| Disease activity (T0)1 | N/A | 245.0 ± 99.3 (CDAI)2 | 12.9 ± 2.8 (CAI) |

| Site of disease n (%): | |||

| Small bowel/pouch | 13 (32.5) | ||

| Large bowel | 4 (10) | 10 | |

| Ileum-colon | 23 (57.5) | ||

| Steroid therapy at enrolment (%) (≥ 0.7 mg/kg per day) | 39 (78) | 30 (75) | 9 (90) |

| Concomitant medications n (%): | |||

| Salicylates | 29 | 21 (52.5) | 8 (80) |

| 6-MP/azathioprine | 31 | 28 (70) | 3 (30) |

| Antibiotics | 25 | 24 (60) | 1 (10) |

Patients presented with mild to moderate IBD, as defined by a score of 150-350 (or less in steroid-dependent patients) on the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) for CD patients[25], and a score of > 10 (or less in steroid-dependent patients) on the Clinical Activity Index (CAI) for UC patients[26]. Indications for IFX treatment were disease severity, steroid-dependent disease (unable to reduce prednisolone < 10 mg/d), steroid-refractory disease (active disease with prednisolone up to 0.7 mg/kg per day), or contraindication to steroids (e.g., diabetes, osteoporosis, acne, mood disturbance and severe hypertension). Exclusion criteria were cancer or history of cancer, pregnancy, chronic heart failure, previous tuberculosis, or presence of symptomatic intestinal strictures or abscesses.

All patients were allowed to continue concomitant therapies such as 5-aminosalicylates, immunosuppressive agents [azathioprine (AZA), 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), methotrexate], and antibiotics; patients on steroids discontinued treatment using a tapering regimen of 10 mg weekly starting at the first IFX infusion.The study protocol was approved by the University Ethic Committee.

Clinical and instrumental assessment was performed within the 3 wk before IFX induction treatment. Blood samples were collected, after overnight fasting, prior to IFX infusion for routine laboratory tests, including inflammatory [C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)] and biochemical parameters. A chest X ray evaluation was performed before the first IFX infusion in order to exclude previous or latent tuberculosis infection. Patients’ symptoms were routinely recorded before each infusion, in order to calculate the CDAI and CAI.

All 50 IBD patients were treated with an induction regimen consisting of 3 intravenous (iv) infusions of IFX at a dose of 5 mg/kg for induction of remission (wk 0, 2, 6 for CD; wk 0, 4, 8 for UC). Eight weeks after the third infusion, clinical assessment was repeated in all patients to evaluate treatment efficacy: in CD patients, the clinical response was defined as a ≥ 70 point reduction in the CDAI score, and clinical remission was defined as a CDAI score ≤ 150; in UC patients, clinical response was defined as a CAI score ≤ 10 points, and inactive disease as a CAI score ≤ 4. Thereafter, all responders (both CD and UC patients) received IFX maintenance infusions at 8-wk intervals. Written patient’s consent was obtained before every IFX infusion.

All adverse events were recorded by means of direct questioning of patients. Infusion reactions to IFX were classified as either acute or delayed. Any adverse reaction, during or within 24 h of an initial or subsequent IFX infusion, was considered as an acute infusion reaction. A delayed infusion reaction refers to any adverse reaction occurring from 24 h to 14 d after re-treatment with IFX. Acute and delayed reactions were further defined as mild, moderate, or severe, according to the severity of signs and symptoms reported by the patient. Serum sickness-like reactions included any IFX-related event that occurred 1 to 14 d after infusion and consisted of a cluster of symptoms such as myalgias and/or arthralgias with fever and/or rash. Severe infection, cancer, and death were considered as serious adverse events if potentially related to IFX treatment.

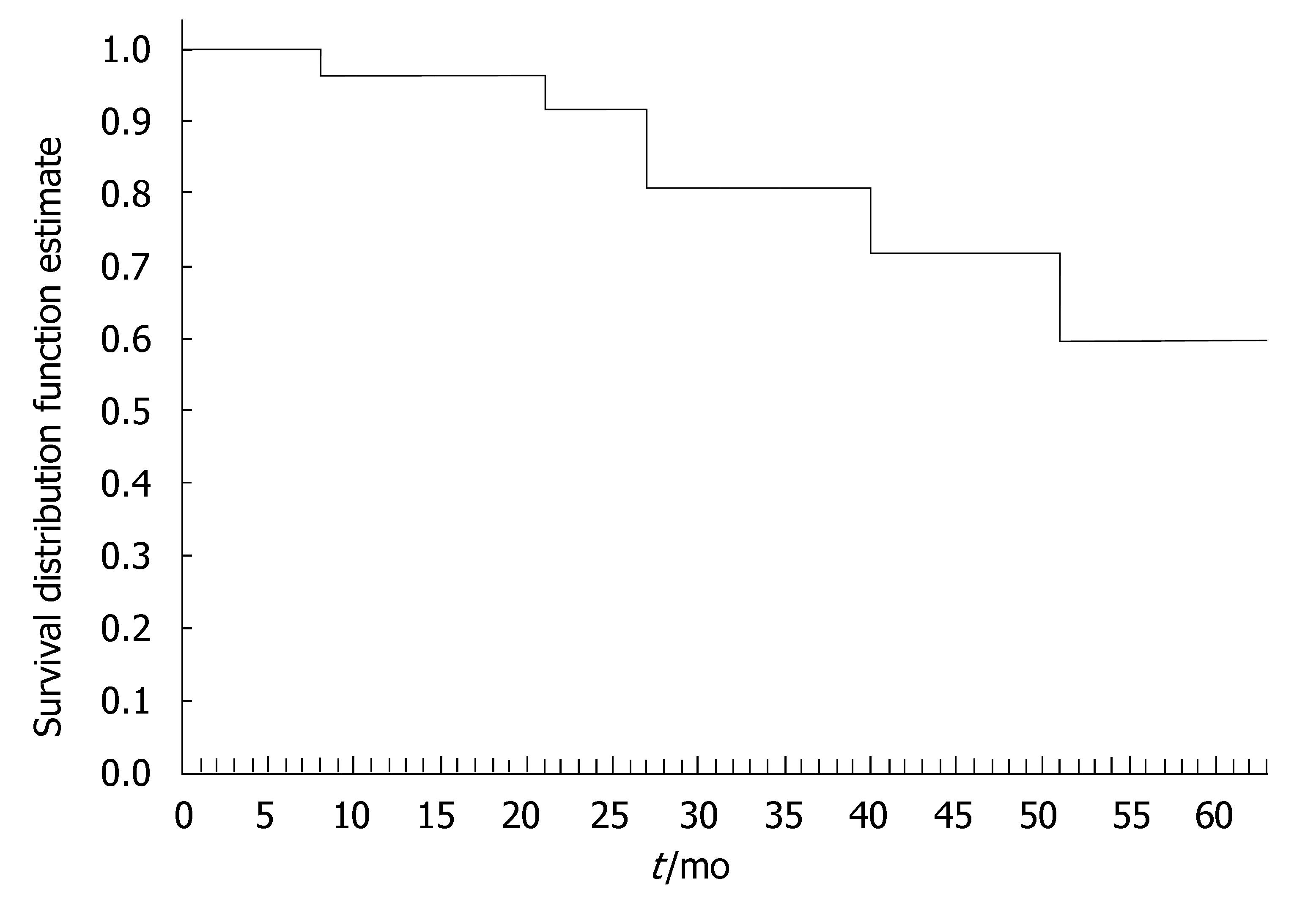

Results related to continuous data are expressed as median (range). The cumulative probability of relapse was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.

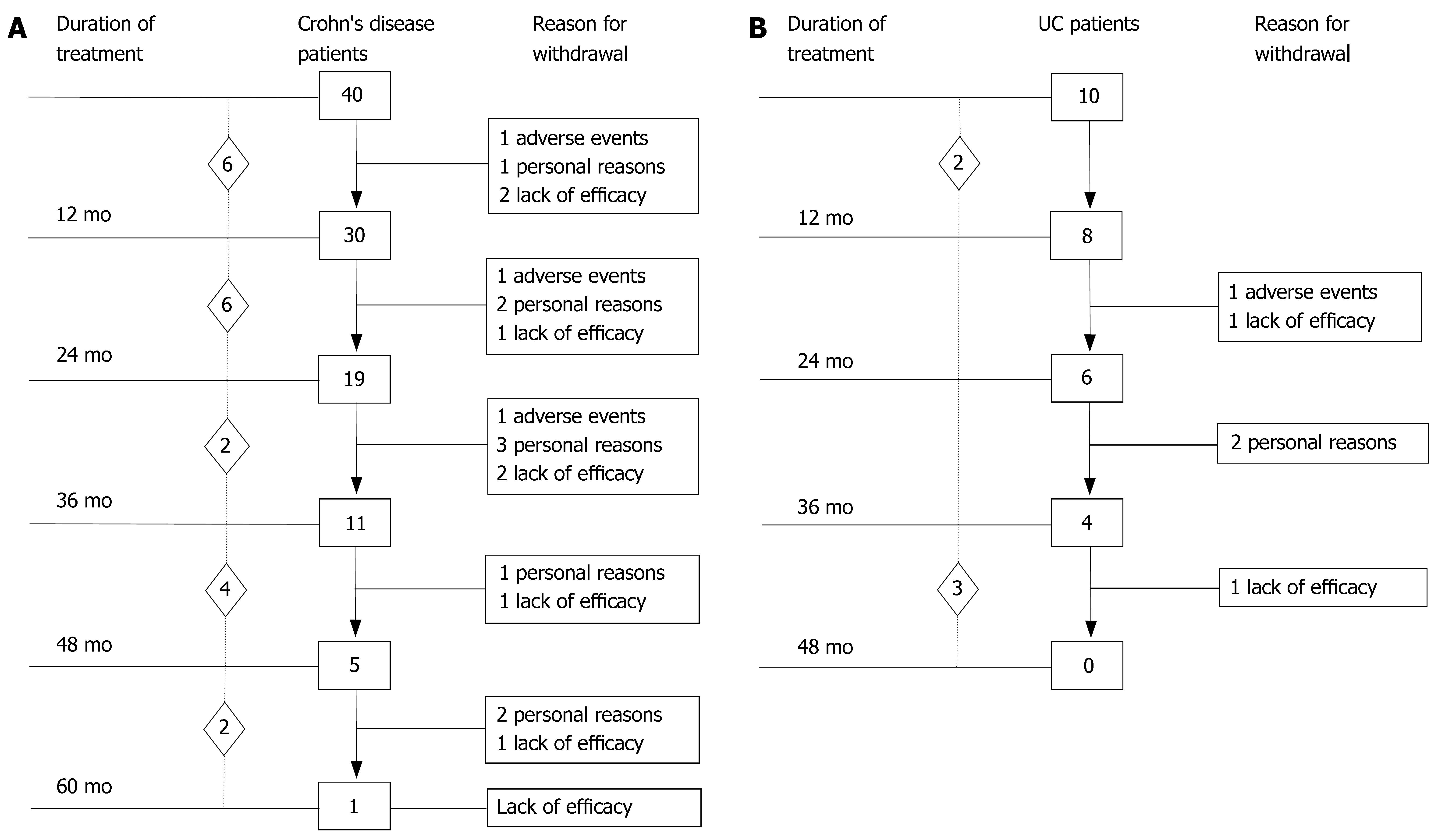

Baseline demographic and clinical data of the 50 patients (40 CD, 10 UC) who underwent induction therapy followed by scheduled maintenance therapy every 8 wk are outlined in Table 1. The summary of IBD patients’ outcome observed at 12-mo intervals (endpoints) during IFX maintenance therapy is shown in Figure 1. A total of 637 IFX infusions were administered (493 in CD, 144 in UC). The median duration of scheduled IFX treatment in the whole group of IBD patients was 27 (range, 4-64) mo.

The 40 CD patients undergoing the maintenance treatment strategy had a median disease duration of 9.2 years (range, 0.3-22.2). At baseline, all patients presented luminal disease; 6 patients had also draining fistulas (4 perianal and 2 recto-vaginal fistulas). Median number of IFX infusions was 15 (range, 4-25). The median duration of IFX treatment was 27 (range, 4-64) mo. Of the 40 CD patients, 35 (87.5%) underwent scheduled infusion strategy every 8 wk. In 3 patients (7.5%), showing a progressive loss of response (i.e., increase in CDAI and serum CRP level), the dose intervals were reduced to 6 wk; in 2 patients (5%), on account of stable clinical remission, the infusion intervals were prolonged to 12 wk. In 29 out of 37 CD patients (78%) the initial clinical improvement remained unchanged during IFX scheduled treatment, with CDAI below the remission level (< 150) throughout the maintenance period (Table 2). The median duration of remission during IFX treatment was 25.5 (range, 4-59) mo. Of the 29 CD patients, the 9 (31%) who chose to discontinue IFX scheduled treatment, were still relapse-free at a median of 16 (range, 5-30) mo after the last infusion; all these patients were on concomitant immunomodulatory treatment; 2 CD patients were lost at follow-up. Twenty CD patients are currently on IFX treatment with a median duration of therapy of 20 (range, 5-57) mo. Of the 40 CD patients, 8 patients (20%) who showed worsening of clinical symptoms underwent surgery for intestinal strictures and/or abdominal abscesses. These patients presented with higher baseline values of acute phase reactants - in terms of serum ESR and CRP levels - compared to the patients not undergoing surgery. The difference was not significant. The cumulative probability curve of maintaining the initial response in those patients with clinical benefit at the third infusion is shown in Figure 2. The cumulative probability of being free of relapse in CD patients with complete response was: 97.2% (CI: 91.8-100%) at 12 mo, 90.3% (CI: 79.7-100) at 24 mo, 81.7% (CI: 66.9-96.5%) at 36 mo, 73.5% (CI: 53.3-93.7%) at 48 mo, and 61.3% (CI: 33.6-88.9%) at 51 mo. In this study, fistula closure was not considered as a goal of the clinical outcome.

| IBD (CD + UC) | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | ||||

| IFX infusions total number | 637 | 493 | 144 | |||

| Median number (range) | 15 (4-25) | 15 (4-25) | 14.5 (6-22) | |||

| Median duration (mo) of IFX therapy (range) | 27 (4-64) | 27 (4-64) | 24.5 (6-46) | |||

| No. patients maintaining remission with IFX (%) | 41/50 | 82 | 32/40 | 80 | 9/10 | 90 |

| Median duration (mo) of remission during IFX treatment (range) | 25 (4-59) | 25.5 (4-59) | 25 (6-46) | |||

| No. patients discontinuing therapy during clinical remission (%) | 13/38 | 34 | 9/29 | 31 | 4/9 | 44 |

| Median duration (mo) of remission after treatment discontinuation (range) | 15.5 (4-30) | 16 (5-30) | 6.5 (4-16) | |||

| No. patients on corticosteroids1 during maintenance with IFX (%) | 1/50 | 2 | 10/40 | 25 | 1/10 | 10 |

Ten UC patients who underwent scheduled re-treatment every 8 wk as maintenance protocol had a median disease duration of 9.3 (range, 2-15) years (Table 2). The median number of IFX infusions was 14.5 (range, 6-22). Median duration of IFX treatment was 24.5 (range, 6-46) mo. In 9/10 (90%) UC patients, the CAI score remained below the remission level (< 4) throughout the maintenance period. The median duration of remission during IFX treatment was 25 (range, 6-46) mo. Of the 9 UC patients, 4 withdrew from scheduled treatment due to non compliance (n = 2) and to adverse events (n = 2) after a median time of 24.5 (range, 21-46) mo and were still relapse-free after a median time of 6.5 (range, 4-16) mo after the last IFX infusion; 3 of these patients were on concomitant immunomodulatory treatment. One UC patient, who showed a gradual loss of benefit, underwent surgery for flare up of the disease 24 mo after starting scheduled treatment. Five UC patients are currently on IFX therapy with a median duration of therapy of 36 (range, 6-39) mo. In patients who discontinued IFX treatment, endoscopic evaluation performed before withdrawal revealed complete mucosal healing in all cases.

At baseline, 39 (78%) IBD patients were on steroid therapy; namely, 30/40 (75%) CD patients and 9 out of 10 (90%) UC patients required a median corticosteroid dose of 0.7 mg/kg per day. All patients were able to discontinue corticosteroids following IFX induction therapy, but 10/40 (25%) CD patients and 1/10 (10%) UC patients required reintroduction of steroid therapy during IFX scheduled treatment. Moreover, in patients who required concomitant steroid therapy, the median daily corticosteroid dose decreased to 0.25 mg/kg per day. The 10 CD and 4 UC patients, who discontinued scheduled treatment and remained relapse-free, did not require steroid therapy after the last IFX infusion.

Of the 50 IBD patients, 16 (32%) experienced at least 1 adverse event: number and type of adverse events are listed in Table 3. Of the 50 IBD patients, 3 (6%) experienced moderate acute infusion reactions characterized by headache, dizziness, nausea, flushing, chest pain, dyspnoea, and pruritus, which developed after the second infusion. All 3 patients were successfully reinfused following intravenous hydrocortisone (200 mg) premedication before any subsequent IFX infusion. One patient presented serum sickness-like symptoms within 10 d of the third IFX infusion, developing arthralgias, myalgias, and fever; laboratory tests showed non-viral acute liver failure. The patient was treated with a high dose of iv corticosteroids and fully recovered after prolonged hospitalization. IFX treatment was discontinued in this patient.

| Adverse event | IBD (CD + UC) | Crohn’s disease | Ulcerative colitis |

| Acute infusion reaction (%) (Mild, moderate, severe) | 3/50 (6) | 3/40 (7.5) | 0 |

| Delayed infusion reaction (%) (Serum sickness-like) | 1/50 (2) | 1/40 (2.5) | 0 |

| Opportunistic infection (%) | 9/50 (18) | 8/40 (20) 5 HSV 1 VZV 2 atypical pneumoniae | 1/10 (10) 1 HSV |

| Lymphoproliferative diseases | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignant disorder (%) | 3/50 (6) | 2/40 (5) | 1/10 (10) |

Of the 50 IBD patients, 9 (18%) presented opportunistic infections during maintenance therapy. Six cases of viral infections occurred (5 herpes simplex virus and 1 varicella-zoster virus) in 5 CD patients and 1 UC patient had herpes simplex virus. Atypical pneumonia developed in 2 CD patients; full recovery was achieved in both patients following antibiotic therapy. All these patients were on concomitant immunomodulatory treatment which was withdrawn upon diagnosis. All infections developed within the first year of treatment and, in 3 patients, viral infections recurred during IFX maintenance treatment.

Three patients (6%) developed neoplasia during maintenance treatment (Table 4). Median time interval between the first infusion and diagnosis of neoplasia was 21 (range, 14-24) mo. Median number of IFX infusions was 10 (range, 6-13). Two patients with neoplasia were on concomitant immunomodulatory treatment (azathioprine). The histological types of neoplasia were gastric adenocarcinoma (T2aN0M0), which subsequently developed into peritoneal carcinomatosis and Krukemberg tumor, and endometrioid carcinoma (T1cN0M0), both in CD patients; breast cancer (T2mN3M0) developed in one UC patient.

| Patients | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Gender | F | F | F |

| Disease | Ulcerative colitis | Crohn’s disease | Crohn’s disease |

| Disease duration (yr) | 22 | 3 | 3 |

| Site of disease | Left colon | Ileum-colon | Ileum-colon |

| Type of neoplasia (TNM) | Breast cancer (T2mN3M0) | Gastric cancer (T2aN0M0) | Endometrial cancer (T1cN0M0) |

| Concomitant medication | Azathioprine | Azathioprine/cyprofloxacine/metronidazole | Azathioprine/ cyprofloxacine/ metronidazole |

| N. IFX infusions | 13 | 6 | 10 |

| Months since first IFX infusion | 21 | 24 | 14 |

One CD patient, aged 68 years, who withdrew from the maintenance treatment protocol (9 infusions within 13 mo) because of complete disease remission, died of acute myocardial infarction 10 mo after the last IFX infusion. The patient did not present with any cardiovascular risk factors, except for mild chronic renal failure, not requiring medical therapy and/or dialysis. The event was considered unrelated to IFX as it occurred 10 mo after the last infusion.

Despite the large amount of literature demonstrating the efficacy of IFX for the induction of remission in moderate to severe IBD, few data are available regarding the use of IFX for more than 12 mo or for more than 8 doses in IBD patients. Results of this retrospective study confirm current data on the efficacy of IFX in inducing a rapid clinical response in CD and support the finding, emerging from uncontrolled study data, of prolonged clinical efficacy in maintaining long-lasting remission beyond 1 year of treatment. While the efficacy of IFX therapy in the treatment of CD it is well established, only few studies have been performed on the use of IFX in UC. Järnerot et al[16] found IFX to be an effective rescue therapy in patients experiencing an acute flare up of UC, leading to a significant reduction in the emergency colectomy rate. Moreover, Rutgeerts et al[17] were the first to demonstrate that IFX can induce and maintain a clinical response and remission up to 54 wk of scheduled treatment in patients with moderately to severely active UC showing an inadequate response to conventional therapy. No data are yet available concerning the efficacy and safety of IFX treatment lasting for more than 1 year in UC. In our study population the median duration of IFX treatment was 27 mo in CD patients and 24.5 mo in UC patients, during which most of the patients (80 % of CD patients and 90% of UC patients) remained relapse free, following the clinical response or remission obtained with the induction treatment phase. It is worthwhile stressing that at enrolment, all these patients had active disease despite conventional therapy (or had a steroid-dependent disease). At baseline, considering all IBD patients, 58.5% were receiving 5-aminosalicylates, 78% corticosteroids, and 75.6% immunosuppressants. Moreover, compared to the 78% of patients on corticosteroids at baseline, only 25% needed concomitant corticosteroid therapy during IFX maintenance treatment, with a decreased median daily corticosteroid dose (0.7 mg/kg per day vs 0.25 mg/kg per day). The steroid-sparing effect of IFX was another important finding emerging from our study, which confirmed the efficacy of a scheduled treatment regimen in avoiding the well-known morbidity associated with long-term corticosteroid therapy[4,7].

Interestingly, long-term IFX therapy in IBD has been demonstrated to potentially modify the course of the disease. Indeed, 9 out of the 29 CD and 4 out of the 9 UC patients, who discontinued IFX scheduled treatment were still relapse-free after a median of 16 (range, 5-30) and 6.5 (range, 4-16) mo since the last IFX infusion, respectively. All these patients were off steroids and 12 were on immunosuppressants. Before stopping therapy, endoscopic evaluation was performed only in the subgroup of UC patients, showing complete mucosal healing in all. This result could account for the sustained clinical benefit maintained after withdrawal of treatment.

Long-term safety is an emerging and important issue as IFX use and indications are rapidly increasing worldwide. Recently, large retrospective studies have evaluated the incidence of serious adverse events and onset of neoplasia in CD patients treated with IFX[18-24,27]. Colombel et al[27], who studied 500 CD patients for a median of 17 (range, 0-48) mo with a median of 3 IFX infusions, reported the presence of 8.6% serious adverse events, 6.0% of which were considered possibly related to IFX therapy. In our study, 32% of IBD patients experienced at least 1 adverse event; 8% of the patients had an infusion reaction (3 patients experienced an acute infusion reaction and 1 a serum sickness-like disease). Moreover, in our study population, the incidence of opportunistic infections was 18%, which is higher than that observed in the study by Colombel et al[27] (8.2%). This finding could be due both to the longer scheduled treatment protocol and the concomitant use of immunomodulatory treatment (AZA or 6-MP). Albeit, the long duration of scheduled treatment associated with the concomitant use of immunomodulators may give rise to the risk of opportunistic infections; regular maintenance therapy has been proven to reduce the number of infusion reactions with respect to episodic dosing, which is more immunogenic, as demonstrated by the results of the ACCENT I trial[11]. In fact, in the study by Hanauer et al[11],the antibodies to IFX (ATI), which may be associated with decreased clinical response and increased risk of infusion reactions, were detected at higher rate in the episodic-treated group (30%) compared to the maintenance strategy protocol (8%). Comparable results emerged from the studies by Baert et al[19] and Farrell et al[28], in which IFX was used episodically, thus demonstrating that the formation and concentrations of ATI were correlated with lower post-infusion serum IFX concentrations and with the need to shorten infusion intervals. Moreover, in patients who underwent bowel surgery after IFX withdrawal, no increase in the number of severe infections or surgical complications was observed in the perioperative period (data not shown).

An interesting finding emerging from our study, for which further investigation is necessary, concerns the relatively large number of malignancies (6%) observed in our IBD patients treated with IFX. In fact, the high incidence of solid tumors is somewhat inconsistent with the results reported so far. Biancone et al[21], in their multi-centre case-controlled study, evaluated the risk of developing neoplasia in IFX-treated CD patients: the incidence of newly diagnosed neoplasia was comparable in the 2 groups of CD patients, treated (2.2%) or not treated (1.73%) with IFX. Colombel et al[27], in a retrospective study found that 3 out of 500 of the CD patients treated with IFX had a malignant disorder, possibly related to biologic therapy. The fact that our study did not include a control group and consisted of a rather heterogeneous and relatively small population makes it difficult to establish a direct cause-effect relationship between anti-TNF-α therapy and the increased risk of developing malignancies. However, it should be pointed out that a slight difference was observed in terms of mean number of IFX infusions between patients who developed malignancies and those who did not (9.66 vs 14.6, respectively). This result would appear to suggest that there is no linear dose-dependent increase in risk.

Another important issue concerns the risk of hematologic malignancies related to the use of biologic therapies in IBD. It is well known that patients with long-standing IBD treated with immunomodulatory drugs may be more susceptible to developing lymphoproliferative disease[29-32]. Even though the use of TNF-α blocking agents has been associated with an increased risk of developing lymphoma[32], a finding, however, not confirmed by the data of a large US-based CD registry (TREAT)[22], we did not observe any cases of hematologic malignancy in our study population.

The results from this study need to be interpreted with an understanding of both the strengths and limitations of retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data. Although it allowed us to have a long term follow-up, the patients could have not been monitored as rigorously as prospective, randomized controlled studies. In any event, these limitations are not relevant to the analysis of efficacy of IFX treatment in IBD and of serious infections reported in this setting.

In conclusion, IFX scheduled treatment has proven to be an effective strategy in our IBD patient population for long-term maintenance of clinical remission. The scrupulous selection of patients to be started on IFX therapy is a fundamental issue, not only to obtain maximum efficacy, but also to avoid serious adverse events. A note of caution is mandatory when considering the possible risk of malignancy associated with the use of anti-TNF-α therapy. Further studies on larger series are needed to further clarify these important aspects.

For many years, corticosteroids have represented the cornerstone of therapy for induction of remission in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD); however, long-lasting remission was not achieved and the side-effects emerging with long-term use exceeded the clinical benefits. Immunomodulators have been demonstrated to be efficacious as adjunctive therapy and as steroid-sparing agents. The introduction of biological agents in the therapeutic armamentarium for Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) has significantly changed the treatment strategies and outcomes of these patients.

Despite the large amount of literature demonstrating the efficacy of infliximab (IFX) for the induction of remission in moderate to severe IBD, few data are available regarding the use of IFX for more than 12 mo or for more than 8 doses in IBD patients. Some safety issues are associated with IFX use, mostly related to the development of adverse events (e.g., opportunistic infections, autoimmune disorders, and infusion reactions). Major concerns are related to the reactivation of latent tuberculosis and development of malignancy, even if there is no clear evidence that the use of IFX increases the incidence of solid cancers.

Colombel et al[27] studied 500 CD patients for a median of 17 mo (range, 0-48) with a median of 3 IFX infusions and reported the presence of 8.6% serious adverse events, 6.0% of which were considered possibly related to IFX therapy. Hanauer et al[11] found that the antibodies to IFX, which may be associated with decreased clinical response and increased risk of infusion reactions, were detected at higher rate in the episodic-treated group (30%) compared to the maintenance strategy protocol (8%). Comparable results emerged from the studies by Baert et al[19] and Farrell. Biancone et al[21], in their multi-centre case-controlled study, evaluated the risk of developing neoplasia in IFX-treated CD patients: the incidence of newly diagnosed neoplasia was comparable in the 2 groups of CD patients, treated (2.2%) or not treated (1.73%) with IFX.

IFX scheduled treatment has proven to be an effective strategy in our IBD patient population for long-term maintenance of clinical remission. The scrupulous selection of patients to be started on IFX therapy is a fundamental issue, not only to obtain maximum efficacy, but also to avoid serious adverse events.

Infliximab is a chimeric monoclonal IgG1 antibody directed against TNF-α able to almost completely neutralize its biological activity. Crohn’s Disease Activity Index was used to monitor Crohn’s disease activity and the Clinical Activity Index was used for assessing UC activity.

This article contains valuable information that would be useful for practicing clinicians.

S- Editor Ma N L- Editor Mihm S E- Editor Li JL

| 1. | Podolsky DK. Inflammatory bowel disease (2). N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1008-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lichtenstein GR, Yan S, Bala M, Hanauer S. Remission in patients with Crohn's disease is associated with improvement in employment and quality of life and a decrease in hospitalizations and surgeries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:182-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1493] [Cited by in RCA: 1485] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schreiber S. Medical treatment: an overview. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. London: Churchill Livingstone 2003; 297-301. |

| 5. | Hanauer SB, Sandborn W. Management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:635-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Faubion WA, Loftus EV, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:255-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 833] [Cited by in RCA: 792] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53 Suppl 5:V1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 746] [Cited by in RCA: 772] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Scallon BJ, Moore MA, Trinh H, Knight DM, Ghrayeb J. Chimeric anti-TNF-alpha monoclonal antibody cA2 binds recombinant transmembrane TNF-alpha and activates immune effector functions. Cytokine. 1995;7:251-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 501] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, Mayer L, Present DH, Braakman T, DeWoody KL, Schaible TF, Rutgeerts PJ. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. Crohn's Disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2328] [Cited by in RCA: 2268] [Article Influence: 81.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, Podolsky DK, Sands BE, Braakman T, DeWoody KL. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1969] [Cited by in RCA: 1839] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541-1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2987] [Cited by in RCA: 3055] [Article Influence: 132.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1581] [Cited by in RCA: 1553] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cohen RD, Tsang JF, Hanauer SB. Infliximab in Crohn's disease: first anniversary clinical experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3469-3477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Probert CS, Hearing SD, Schreiber S, Kühbacher T, Ghosh S, Arnott ID, Forbes A. Infliximab in moderately severe glucocorticoid resistant ulcerative colitis: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2003;52:998-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sands BE, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts PJ, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, Targan SR, Podolsky DK. Infliximab in the treatment of severe, steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:83-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Järnerot G, Hertervig E, Friis-Liby I, Blomquist L, Karlén P, Grännö C, Vilien M, Ström M, Danielsson A, Verbaan H. Infliximab as rescue therapy in severe to moderately severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1805-1811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 774] [Cited by in RCA: 768] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462-2476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2744] [Cited by in RCA: 2885] [Article Influence: 144.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Cheifetz A, Smedley M, Martin S, Reiter M, Leone G, Mayer L, Plevy S. The incidence and management of infusion reactions to infliximab: a large center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1315-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Van Assche G, D' Haens G, Carbonez A, Rutgeerts P. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:601-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1523] [Cited by in RCA: 1520] [Article Influence: 69.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vermeire S, Noman M, Van Assche G, Baert F, Van Steen K, Esters N, Joossens S, Bossuyt X, Rutgeerts P. Autoimmunity associated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha treatment in Crohn's disease: a prospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:32-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Biancone L, Orlando A, Kohn A, Colombo E, Sostegni R, Angelucci E, Rizzello F, Castiglione F, Benazzato L, Papi C. Infliximab and newly diagnosed neoplasia in Crohn's disease: a multicentre matched pair study. Gut. 2006;55:228-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, Salzberg BA, Diamond RH, Chen DM, Pritchard ML, Sandborn WJ. Serious infections and mortality in association with therapies for Crohn's disease: TREAT registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:621-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 654] [Cited by in RCA: 635] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Vermeire S. Review article: Infliximab therapy for inflammatory bowel disease--seven years on. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:451-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shih CE, Bayless TM, Harris ML. Maintenance of long term response to infliximab over 1 to 5 years in Crohn's disease including shortening dosing intervals or increasing dosage. Gastroenterology. 2004;126 Supp l2:A631. |

| 25. | Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F. Development of a Crohn's disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439-444. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Lichtiger S, Present DH. Preliminary report: cyclosporin in treatment of severe active ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1990;336:16-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Egan LJ, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The safety profile of infliximab in patients with Crohn's disease: the Mayo clinic experience in 500 patients. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:19-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 29.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Farrell RJ, Alsahli M, Jeen YT, Falchuk KR, Peppercorn MA, Michetti P. Intravenous hydrocortisone premedication reduces antibodies to infliximab in Crohn's disease: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:917-924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Kliewer E, Wajda A. Cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Cancer. 2001;91:854-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Greenstein AJ, Gennuso R, Sachar DB, Heimann T, Smith H, Janowitz HD, Aufses AH. Extraintestinal cancers in inflammatory bowel disease. Cancer. 1985;56:2914-2921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gyde SN, Prior P, Macartney JC, Thompson H, Waterhouse JA, Allan RN. Malignancy in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1980;21:1024-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ljung T, Karlén P, Schmidt D, Hellström PM, Lapidus A, Janczewska I, Sjöqvist U, Löfberg R. Infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: clinical outcome in a population based cohort from Stockholm County. Gut. 2004;53:849-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |