Published online Oct 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i38.5108

Revised: July 28, 2007

Accepted: August 8, 2007

Published online: October 14, 2007

AIM: To assess values of 24-h esophageal pH-monitoring parameters with dual-channel probe (distal and proximal channel) in children suspected of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

METHODS: 264 children suspected of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) were enrolled in a study (mean age χ = 20.78 ± 17.23 mo). The outcomes of this study, immunoallerrgological tests and positive result of oral food challenge test with a potentially noxious nutrient, enabled to qualify children into particular study groups.

RESULTS: 32 (12.1%) infants (group 1) had physiological GER diagnosed. Pathological acid GER was confirmed in 138 (52.3%) children. Primary GER was diagnosed in 76 (28.8%) children (group 2) and GER secondary to allergy to cow milk protein and/or other food (CMA/FA) in 62 (23.5%) children (group 3). 32 (12.1%) of them had CMA/FA (group 4-reference group), and in remaining 62 (23.5%) children neither GER nor CMA/FA was confirmed (group 5). Mean values of pH monitoring parameters measured in distal and proximal channel were analyzed in individual groups. This analysis showed statistically significant differentiation of mean values in the case of: number of episodes of acid GER, episodes of acid GER lasting > 5 min, duration of the longest episode of acid GER in both channels, acid GER index total and supine in proximal channel. Statistically significant differences of mean values among examined groups, especially between group 2 and 3 in the case of total acid GER index (only distal channel) were confirmed.

CONCLUSION: 24-h esophageal pH monitoring confirmed pathological acid GER in 52.3% of children with typical and atypical symptoms of GERD. The similar pH-monitoring values obtained in group 2 and 3 confirm the necessity of implementation of differential diagnosis for primary vs secondary cause of GER.

- Citation: Semeniuk J, Kaczmarski M. 24-hour esophageal pH-monitoring in children suspected of gastroesophageal reflux disease: Analysis of intraesophageal pH monitoring values recorded in distal and proximal channel at diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(38): 5108-5115

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i38/5108.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i38.5108

Acid gastroesophageal reflux (GER) in children at any age, could be the reason of various clinical manifestation (typical and atypical) of variable intensity, dependent on the range of reflux (high reflux, low reflux)[1-9]. On the basis of reflux symptoms it is hardly possible to differentiate primary GER from GER secondary to allergy to cow milk protein and/or other food (CMA/FA)[10-13]. In children suspected of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), 24-h esophageal pH-monitoring is a diagnostic procedure that enables to confirm or exclude pathological reflux of acid gastric contents into esophagus i.e. acid GER[14-20]. Diagnostic procedure, including food allergy contribution in GER, is necessary to distinguish primary GER from secondary GER. Such procedure includes immunoallergological tests i.e. Prick tests, cIgE, sIgE[2,12,21-25]. Positive result of food oral challenge test with potentially noxious nutrient (biological trial) confirmed contribution of food allergy in triggering off reflux symptoms[25,26]. Comparative analysis of 24-h intraesophageal pH monitoring with dual-channel probe (distal and proximal channel) in children suspected of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

264 children suspected of GERD, of both sexes (140 boys-53.0% and 124 girls-47.0%) were enrolled in a study. Patients were 1.5 mo to 102 mo old, mean age χ = 20.78 ± 17.23 mo. Information gathered at interview revealed that various gastrointestinal diseases appeared in family histories of all patients.

24-h intraesophageal pH-monitoring was performed with antimony dual-channel pH monitoring probe (distal channel/distal and proximal channel) and a device recording the values Digitraper MK III, Synectics Medical. Antimony electrode was calibrated with buffer solutions of pH = 7.0 and pH = 1.0. pH-monitoring probe, 2.1 diameter, was positioned in esophagus through one of the nostrils and pharynx with distal channel (2) at the height of 3-5 cm, and proximal channel (1) at 10, 15 or 20 cm above the upper edge of lower esophageal sphincter (LES). To localize the probe Strobel’s mathematical mode, radiological examination, and manometry of LES were carried out[27-29].

The type of dual-channel probe (sensors spacing 5, 10 or 15 cm) and its positioning in esophagus depended on the age of a patient (various lengths of esophagus) and clinical manifestation of GER (typical or atypical symptoms). The analysis of the type of reflux (acid/non-acid) was based on the pH monitoring values recorded in distal channel (2).

Recording from proximal channel (1) of the probe above LES (at various height) enabled the assessment of the range of reflux (high/low reflux) and the control of the proper positioning of the probe. It was also possible to compare the number of acid and non-acid refluxes in both positions of pH-monitoring. Esophageal pH monitoring always began in the morning, after fasting all night. The study lasted 24 h and comprised night sleep.

Patients discontinued particular medicines 3 d before the test. Among these medicines were: antacids, gastrokinetics, medications affecting tension of LES. Proton pomp inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists were discontinued 7 d before the test[30].

Computer calculations of measurements obtained from both channels concerned the following pH-monitoring parameters: number of episodes of acid GER (intraesophageal pH below 4.0), number of episodes of acid GER lasting more than 5 min (so-called “long episodes”), reflux index i.e. the percentage of time that the pH is below 4.0. ESPGHAN diagnostic criteria were implemented in diagnosis of acid GER in examined children[14,15].

In children below 2 years of age the values of intraesophageal pH-monitoring were juxtaposed against normative values (borderline values) of Vandenplas et al[16,17] and another authors[18,19].

In older children (above 2 years of age) the borderline values at quantitative and qualitative assessment of pathological GER in both channels were[14,15,31-33]: total number of acid GER episodes (pH < 4.0/24 h) = 50; number of episodes of acid GER lasting more than 5 min≤ 2; the percentage of time with pH below 4.0 (%)-total acid GER index = 5.0%; the percentage of time with pH below 4.0 (%)-acid GER index supine = 2.5%.

In order to differentiate pathological GER into primary (idiopathic) and secondary - triggered off or aggravated by CMA/FA, the own diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm was administered in examined children. This algorithm comprises selected immunoallergological tests[10,23-25,34].

Skin tests (Prick): (1) with 12 native food allergens i.e. fresh (cow’s milk, soya, of hen’s egg white, hen’s egg yolk, chicken’s meat, beef, wheat flour, peanuts, bananas, fish, orange, white sesame); (2) with 9 commercial inhalant allergens (SmithKline Beecham-USA) (house dust mites, grass , trees, bushes and weeds pollens, dog’s fur, cat’s fur, mixed feathers, wool).

71 out of 138 children, of different age, with pathological acid GER and 32 children with CMA/FA exclusively, underwent these test once in order to confirm or exclude the ability of early IgE-dependent hypersensitivity to food allergens and/or inhalant allergens (atopic factor influence and or cross reactions) to trigger off symptoms observed. Results of control tests were the point of reference in assessment of reaction to allergens. The diameter of blister ≥ 3 mm assessed after 15-20 min of allergen placement was concerned a positive result of skin Prick tests, compared to negative result of negative control.

Eosinophilia: One-time assessment of relative eosinophilia in full blood count and its analysis were performed in 138 children with pathological acid GER and in 32 children with CMA/FA exclusively. Improper percentage value of eosinophilia, determined in full blood count, was > 5%.

Total IgE concentration (c IgE) in serum-assessed with Fluoro-Fast method (3M Diagnostic Systems, USA): One-time assessment of serum IgE concentration was done in 170 children-138 with acid GER and 32 with CMA/FA exclusively. Serum c IgE concentration > 50 IU/mL was considered as elevated in examined children. Taking into cosideration restricted specificity of one-time measurement of total IgE in diagnosis of atopy, this test was performed together with determination of specific Ig in this particular class for selected food allergens.

Qualitative and quantitative assessment of specific IgE against food allergens (a-s IgE) and inhalant allergens (i-s IgE) with Fluro-Fast method (3M Diagnostic Systems, USA): Assay of allergen specific Ig concentration in examined children enabled confirmation of IgE-dependent pathomechanism of food allergy and determination of food allergens. These tests appeared to be helpful in cases where tests cannot be performed or their results are doubtful, due to various reasons. 103 patients suspected of allergy, with positive Prick tests results (food allergens and/or inhalant allergens and increased total serum IgE concentration) underwent qualitative and quantitative assessment of a-s IgE and i-s IgE. Positive results of specific IgE were: a/a-s IgE against cow milk proteins, hen’s egg white, hen’s egg yolk, soy, fish, orange b/i-s IgE against grass, trees, bushes and weeds pollens, house dust mites and cat’s fur, assayed in serum- presence supported in class ≥ 2-5.

Oral food challenge test[25,26]: Open or blind oral food challenge test (depending on the age of patient) was carried out in order to establish causative relationship between food and clinical symptoms, regardless of pathogenetic mechanisms of allergy (IgE-dependent or IgE-non-dependent)[25]. The first stage of diagnostic procedure preceding the beginning of oral food challenge tests was eliminatory diet implementation, lasting 4 wk in 138 children with acid GER. Diet depended on elimination of the most common food allergens, suspected of triggering off symptoms in examined children. Eliminatory diet was determined on the basis of information gathered from medical history of past nutrition and the results of additional tests (skin Prick tests, s IgE)[25,26]. At the time of study, patients didn’t receive or had maximally reduced antillergic and/or antihistaminic medications. 138 children at various age, with pathological acid GER, after eliminatory diet implementation (milk-free and/or hypoallergic diet) underwent 204 biological oral food challenge tests; 138 (67.6%) with cow’s milk and 66 (32.4%) with other food. In order to establish primary diagnosis, open food challenge test was performed in the 104 youngest children (below 3 years of age) and blind food challenge test in 34 children (above 3 years of age) with mainly cow’s milk (low-lactose Bebilon, Ovita Nutricia) or with other potentially noxious nutrients[25,26]. Every time child spent 1-3 d at hospital (Laboratory of Allergy Diagnostics, of III Department of Pediatrics). Time of appearance of biological reaction in examined child was counted from the last food challenge up to 48-72 h after intake of specific nutrient in native, blind form. Every patient examined received every day observation chart for reporting intensity of clinical manifestation. In case of cow’s milk allergy or soy milk allergy and/or other food allergy the time of challenge test lasted 4 wk. Positive result of food challenge test and/or positive results of immunoallergological tests enabled to qualify a selected 62 children into group 2-children with GER secondary to FA.

In order to exclude the cause of secondary GER other than food allergy, the results of additional examinations performed in patients were analyzed. Among these examinations were: chest and upper gastroinestinal tract X-ray with barium swallow, X-ray or computed tomography of sinuses (in school children). On the basis of the aforementioned examinations, the type, localization and character of coexisting ailments were assessed. In order to confirm or exclude infectious cause of the symptoms presented, the following tests were taken into consideration: full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP, ASO, protein fraction pattern, concentration of IgA, IgM, IgG, IgG antibodies against Helicobacter pylori and iron level. Moreover, bacteriological examinations were performed in some children (tests of blood, urine, faeces, bile, pharyngeal and nasal excretion). Pilocarpine test (chlorine concentration in perspiration) was performed to exclude cystic fibrosis. Moreover, metabolic screening was done by assaying lactic acid, ammonia, acid-base balance parameters in blood[2,9,13,34].

264 children were assigned into specific study groups (Table 1) after consideration of the results of 24-h esophageal pH monitoring, complex differential diagnosis, oral food challenge test with noxious nutrient, eliminatory diet, and nutrition analysis.

| Examined children with reflux symptoms | |||||||||

| Groups ofexamined children | Sex | Age range (mo) | |||||||

| Number | >1.5-4 | >4-16 | >16-102 | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Group 1 physiological GER n =32 | Boys | 17 | 6.4 | 17 | 6.4 | - | - | - | |

| Girls | 15 | 5.7 | 15 | 5.7 | - | - | - | - | |

| Group 2 Primary GER n = 76 | Boys | 39 | 14.8 | - | - | 23 | 8.7 | 16 | 6.1 |

| Girls | 37 | 14 | - | - | 21 | 7.9 | 16 | 6.1 | |

| Group 3 GER + CMA/FA n = 62 | Boys | 33 | 12.5 | - | - | 16 | 6.1 | 17 | 6.4 |

| Girls | 29 | 11 | - | - | 14 | 5.3 | 15 | 5.7 | |

| Group 4 reference group CMA/ FA n = 32 | Boys | 19 | 7.2 | - | - | 7 | 2.6 | 12 | 4.5 |

| Girls | 13 | 4.9 | - | - | 5 | 1.9 | 8 | 3 | |

| Group 5 GER (-) + CMA/ FA (-) n = 62 | Boys | 32 | 12.1 | - | - | 8 | 3 | 24 | 9.1 |

| Girls | 30 | 11.4 | - | - | 10 | 3.8 | 20 | 7.6 | |

| Total | 264 | 100 | 32 | 12.1 | 104 | 39.4 | 128 | 48.5 | |

Acid GER was diagnosed in 170 children. Out of 170 patients (64.4%) with acid GER, of both sexes i.e. 89 boys and 81 girls, 32 (12.1) infants with physiological GER (group 1) were selected. This selected group consisted of 17 boys (6.4%) and 15 girls (5.7%), aged 1.5-4 mo (mean age χ = 2.2 ± 0.48 mo).

The diagnosis was put forward on the basis of the number of reflux episodes exclusively, recorded during pH monitoring. The results of remaining parameters were within the normative reference values (age-related normative values). Due to physiological character of reflux (not complicated), typical for the youngest patients, these infants were not the subject of prospective clinical observation and further clinical analysis.

In 138 children (52.3%) pathological acid GER was diagnosed and classified into primary and secondary GER. These children were assigned into group 2 and 3. Group 2 constituted 76 patients (28.8%) with pathological primary acid GER, of both sexes (39 boys-14.8%, 37 girls-14.0%), aged 4-102 mo (mean age χ = 25.2 ± 27.28 mo). In group 3 were 62 patients (23.5%), of both sexes (33 boys-12.5%; 29 girls-11.0%), aged 74 mo (mean age χ = 21.53 ± 17.79 mo) with pathological GER secondary to CMA/FA.

Acid GER was not confirmed in 94 (35.6%) out of 264 patients with symptoms suggesting GERD. These children were qualified into groups 4 and 5. Group 4-the reference group constituted 32 patients (12.1%), of both sexes (19 boys-7.2%;13 girls-4.9%), aged 7-69 mo (mean age χ = 23.7 ± 12.63 mo) with symptoms typical for cow milk allergy and/or other food allergy (CMA/FA). Group 5 constituted 62 patients (23.5%) (32 boys-12.1%; 30 girls-11.4%), aged 4-102 mo (mean age χ = 31.3 ± 27.98 mo).

Neither reflux cause nor allergic cause of the symptoms were confirmed in these children, and hence they were not the subject of prospective observation and further clinical analysis.

The study was approved by local Bioethical Committee of the Medical University of Białystok and informed parental consent was obtained from parents of examined children.

The statistical analysis of the results comprised arithmetical mean, standard deviation, minimal and maximal values and median-for measurable features and quantitative percentage distribution for qualitative features. To compare the groups, features compatible with normal distribution, assessed with Kolomogorov compatibility test, were assessed together with the post hoc Bonferroni one-way analysis of variance. Features non-compatible with the distribution underwent Kruskal-Wallis test and if the differences were statistically significant, Mann-Whitney test was applied. Statistical significance was P < 0.05. Calculations were performed with the help of statistical package SPSS’12.0 PL.

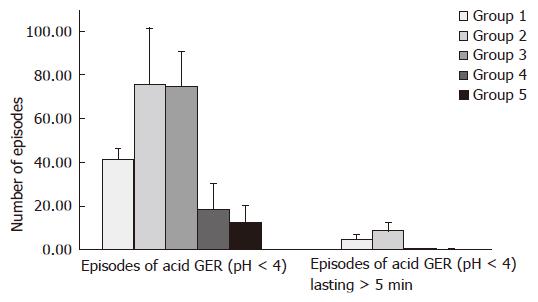

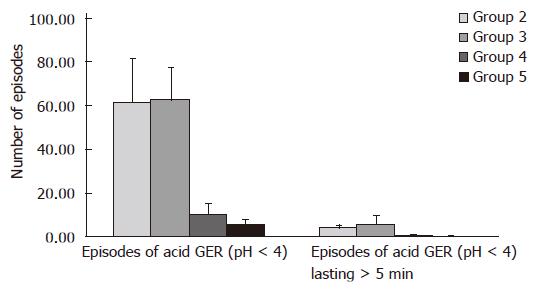

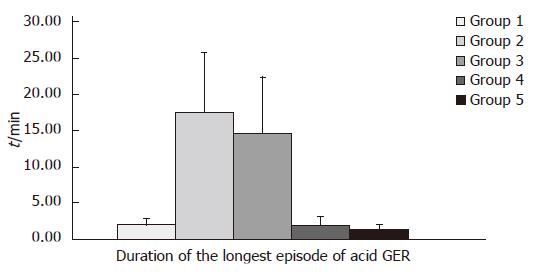

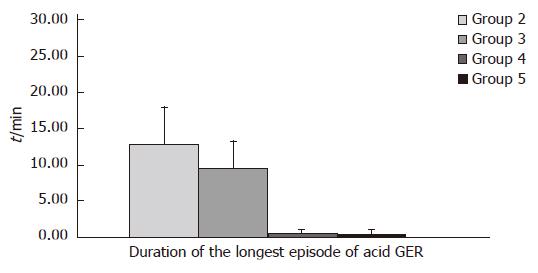

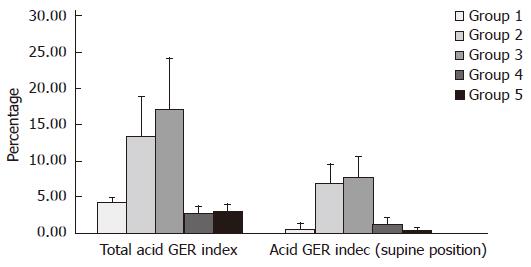

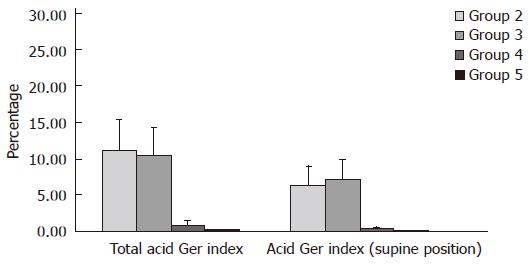

Preliminary comparative analysis of selected values of 24-h intraesophageal pH monitoring parameters with single-channel probe (distal channel) was carried out in 32 children (12.1%) (group 1) and with dual-channel (distal and proximal channel) in 232 children (87.9%) (groups 2, 3, 4 and 5). The results of the analysis are presented in Tables 2, 3 and Figures 1-6 Results of pH esophageal monitoring in group 1 did not undergo comparative analysis with respective values obtained in children from remaining groups. Pathological acid GER was diagnosed in 138 children (52.3%), in 76 children primary GER (group 2) and in 62 children GER secondary to CMA/FA (group 3). Pathological acid GER was not confirmed in 94 children (35.6%), out of which 32 had CMA/FA diagnosed (group 4-reference group). In remaining 62 children neither GER nor CMA/FA were confirmed (group 5). The values of esophageal pH monitoring parameters obtained in individual groups: 2, 3, 4, and 5 were compared against each other. The analysis of mean values of pH monitoring parameters measured in children from individual groups is presented as follows.

| Groups of examined children with specific ailment | pH-monitoring parameters-distal channelrange of values; mean; standard deviation (± SD); median; statistical significance (P) | ||||

| n = 264 | Number of episodes ofacid GER (pH < 4) | Number of episodes of acid GER(pH < 4), lasting > 5 min | Duration of the longestepisode of acid GER (min) | Total acid GER index (%) | Acid GER index(supine position) (%) |

| Statistical significance between the groups (P) | |||||

| Group 2 and 3 | P = 0.0001 | NS | |||

| Group 2 and 4 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 | |||

| Group 2 and 5 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 |

| Group 3 and 4 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 | |||

| Group 3 and 5 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 | |||

| Group 4 and 5 | NS | NS | |||

Distal channel (Table 2, Figure 1): In children with primary GER (group 2) the mean value of the parameter (χ = 75.68 ± 25.61) was similar to mean value (χ = 74.6 ± 16.02) in children with GER and CMA/FA (group 3). These values are higher than mean number of episodes of acid GER, constituting χ = 18.56 ± 11.74 and χ = 12.6 ± 7.74 in group 4 and 5, respectively.

Proximal channel (Table 3, Figure 2): In children from group 2 mean value of the examined parameter (χ = 61.45 ± 20.43) was similar to mean value (χ = 62.48 ± 14.67) in children from group 3. These values are higher than mean number of episodes of acid GER χ = 10.5 ± 4.5 and χ = 5.36 ± 2.09 in group 4 and group 5, respectively.

| Groups of examined childrenwith specific ailment | pH-monitoring parameters-proximal channelrange of values; mean; standard deviation (± SD); median; statistical significance (P) | ||||

| n = 232 | Number of episodes ofacid GER (pH < 4) | Number of episodes of acid GER(pH < 4), lasting > 5 min | Duration of the longestepisode of acid GER (min) | Total acid GER index (%) | Acid GER index(supine position) (%) |

| Statistical significance between the groups (P) | |||||

| Group 2 and 3 | |||||

| Group 2 and 4 | |||||

| Group 2 and 5 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 | P = 0.0001 |

| Group 3 and 4 | |||||

| Group 3 and 5 | |||||

| Group 4 and 5 | |||||

Distal channel (Table 2, Figure 1): In children from group 2 mean value of this parameter (χ = 5.17 ± 1.95) was lower than mean value (χ = 8.87 ± 3.65) in children from group 3. At the same time these values are higher than mean values of parameters χ = 0.33 ± 0.49 and χ = 0.15 ± 0.36 measured in group 4 and 5, respectively.

Proximal channel (Table 3, Figure 2): In children from group 2 mean value of parameter measured (χ = 3.96 ± 1.37) was lower than mean value in group 3 (χ = 5.87 ± 3.64). At the same time these values are higher than mean values of episodes of acid GER lasting more than 5 min: χ = 0.28 ± 0.46 and χ = 0.11 ± 0.32 in group 4 and 5, respectively.

Distal channel (Table 2, Figure 3): In children from group 2 mean value of this parameter (χ = 17.45 ± 8.21) was higher than mean value (χ = 14.61 ± 7.68) in children from group 3. These values were higher than mean time of the longest episode of acid GER: χ = 2.08 ± 1.05 and χ = 1.4 ± 0.66 in group 4 and 5, respectively.

Proximal channel (Table 3, Figure 4): In children from group 2 mean value of parameter measured (χ = 12.91 ± 5.14) was higher than mean value (χ = 9.51 ± 3.78) in children from group 3. At the same time these values are higher than mean time of the longest episode of acid GER: χ = 0.67 ± 0.49 and χ = 0.44 ± 0.62 in group 4 and 5, respectively.

Distal channel (Table 2, Figure 5): In children from group 2 mean value of this parameter (χ = 13.42 ± 5.52) was lower than mean value (χ = 17.17 ± 6.96) in children from group 3. These values are higher than mean values of total acid GER index: χ = 2.69 ± 1.07 and χ = 3.1 ± 0.78 in groups 4 and 5, respectively.

Proximal channel (Table 3, Figure 6): In children from group 2 mean value of this parameter (χ = 11.26 ± 4.18) was higher than mean value (χ = 10.47 ± 3.8) in children from group 3. At the same time these values were higher than mean values of total acid GER index: χ = 0.91 ± 0.68 and χ = 0.37 ± 0.16 in group 4 and 5, respectively.

Distal channel (Table 2, Figure 5): In children from group 2 mean value of this parameter (χ = 6.96 ± 2.64) was lower than mean value (χ = 7.67 ± 2.87) in children from group 3. These values were higher than mean values of supine acid GER index: χ = 1.09 ± 1.06 and χ = 0.39 ± 0.31 in groups 4 and 5, respectively.

Proximal channel (Table 3, Figure 6): In children from group 2 mean value mean value of parameter measured (χ = 6.41 ± 2.64) was lower than mean value (χ = 7.16 ± 2.76) in children from group 3. These values were higher than mean value of supine acid GER index: χ = 0.43 ± 0.22 and χ = 0.09 ± 0.11 in groups 4 and 5, respectively.

The comparative analysis carried out between group 2 and 3 (children with GER) and between group 4 and 5 (children without GER) proved statistically significant differentiation (P < 0.05) of mean values (abnormal distribution) in the case of: number of episodes of acid GER, number of episodes of acid GER lasting more than 5 min and duration of the longest episode of acid GER in both channels (distal and proximal) as well as acid GER index: total and supine, in proximal channel exclusively.

This analysis also confirmed statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) of mean values (normal distribution) in the case of total acid GER index, in distal channel exclusively, among individual groups, especially between group 2 (children with primary GER) and group 3 (children with GER secondary to CMA/FA). However, in the case of supine acid GER, in distal channel, no statistical significance of its mean values between group 2 and group 3 was confirmed.

On the basis of pH monitoring recording at pre-liminary examination in children of individual groups (Table 4), phasic recording of intraesophageal pH monitoring values was registered in 9 children (14.5%) with pathological GER secondary to CMA/FA (group 3) and in 3 children (9.4%) with CMA/FA exclusively (group 4-reference group).

| Groups of examinedchildren | 24-h intraesophageal pH-monitoring - preliminary study | |||||||

| Pathological recording | Regular recording(physiological) | |||||||

| Phasic | Non phasic | Phasic | Non phasic | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Group 11 | ||||||||

| Physiological GER | - | - | - | - | - | - | 32 | 100 |

| n = 32 (100.0%) | ||||||||

| Group 2 | ||||||||

| Primary GER | - | - | 76 | 100 | - | - | - | - |

| n = 76 (100.0%) | ||||||||

| Group 3 | ||||||||

| GER + CMA/FA | 9 | 14.5 | 53 | 85.5 | - | - | - | - |

| n = 62 (100.0%) | ||||||||

| Group 4 reference group | ||||||||

| - | - | - | - | 3 | 9.4 | 29 | 90.6 | |

| n = 32 (100.0%) | ||||||||

| Group 51 | ||||||||

| GER (-) + CMA/FA (-) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 62 | 100 |

| n = 62 (100.0%) | ||||||||

Of 264 examined children, acid GER was confirmed in 170 (64.4%) of them on the basis of 24-h esophageal pH monitoring. In 138 of these children (52.3%) GERD was confirmed.

Age of examined children did not reveal statistically significant differences among individual groups. Among 138 children, GERD was more often attributed to acid GER in boys (72-52.2%) in comparison to girls (66%-47.8%).

On the basis of the results of immunoallergological tests and verifying positive oral food challenge test[25,26], pathological acid GER in 138 children was divided into primary (28.8% of children, group 2) and secondary to CMA/FA (23.5%, group 3). At the same time, on the basis of complex differential diagnosis other causes of acid GER were excluded.

Among 264 children with family history of gastrointestinal tract diseases, acid GER was not confirmed in 94 of them (35.6%).

The assumption of esophageal pH monitoring was that the higher the electrode sensor was positioned, the less number of short-term reflux episodes was recorded, and the total time of reflux is shortened, which is consequent upon better efficiency of neutralizing mechanisms and the ability to self-purification of this part of esophagus[18,20,32,33].

The results of our studies do not support the stated hypothesis completely because the mean values of analyzed pH monitoring parameters in proximal channel were not lower (not statistically significant) than in distal part of esophagus in children with GERD in groups 2 and 3.

Percentage values of the number of episodes of acid GER recorded in proximal channel accounted for 81%, in group 2 and 84% in distal channel, in group 3.

The number of episodes of acid GER lasting more than 5 min recorded in proximal part of esophagus accounted for 76% in group 2, whereas in distal part of esophagus made 66%, group 3.

The duration of the longest episode of acid GER recorded in proximal part of esophagus constituted 74%, group 2, whereas in distal part of esophagus it accounted for 65%, group 3. Total acid GER index recorded in proximal part of esophagus made 84%, group 2 and in distal part of esophagus 61%, group 3. Supine acid GER index in proximal part of esophagus accounted for 92%, group 2 and in distal part of esophagus it made 93%, group 3.

In children with primary GER (group 2) and secondary GER (group 3), the mean values of individual pH monitoring parameters did not reveal significant difference between both channels. On the basis of the results obtained, it appears that there was no significant quantitative difference in the episodes of acid GER, reaching both distal and proximal channel, regardless of the age of examined children.

It was shown that reflux episodes in proximal channel were similar in number only in patients with primary GER (group 2) and those with GER secondary to CMA/FA (group 3). It may be assumed that high gastroesophageal reflux reaching proximal channel is particularly meaningful in children of both groups, but with atypical symptoms, especially of respiratory tract (silent reflux), therefore suggesting the possibility of microaspiration of gastric content into the bronchial tree[2,18-20].

Silent reflux in children below 3 years of age, with recurrent infections of respiratory tract in past history was confirmed on the basis of pH monitoring with single-channel probe in 56% and 57% of children’s gastroenterological centers in Poland[35,36].

According to these data the diagnostic value (sensitivity) of 24-h esophageal pH monitoring in detecting pathological GER accounted for 89% in all patients examined with this type of probe but made only 84% in patients with atypical symptoms.

On the basis of 24-h esophageal pH monitoring with dual-channel probe in children with symptoms out of gastrointestinal tract, within the same age group, in own studies the higher percentage of high gastroesophageal reflux was reported, which accounted for 77.4% and 88.3% in both groups, respectively. The results of own studies give information on the intensity of acid GER reaching distal and proximal part of esophagus, and mean values of examined pH monitoring parameters in distal and proximal part of esophagus reveal statistical significance between the groups. The comparable results of supine acid GER index in distal channel constitute an exception. This differentiation of pH monitoring parameters between the groups appears to be helpful in predicting, who of the examined children is at risk of primary GER, and which symptoms are consequent upon GER secondary to CMA/FA. The result of preliminary study s also important, in which the increasing number of reflux episodes reflecting the higher value of reflux index, and it was comparable in distal and proximal channel, in both study groups.

Italian authors reported the interpretation of graphic recording of intraesophageal pH monitoring, in which they showed a phasic decrease of values after milk meal and their rapid increase after the following meal in children with GER and/or CMA[37].

Quantitative characteristics of patients of individual groups proved that this phasic recording of pH was a common feature in 9 children (14.5%) with GER and CMA/FA (group 3) and in 3 children (9.4%) with CMA/FA (group 4-reference group), which accounted for 12 out of 94 children with cow milk allergy. Interestingly enough, this type of recording of pH monitoring was not observed in any of the children with GER but without allergy.

In conclusion, pH monitoring performed in children with typical and atypical GERD symptoms enabled to diagnose acid GER in 52.3% of all examined patients. In order to define the extent of reflux i.e. the dynamics of each reflux episode, dual-channel probe should be used to intraesophageal pH recording in distal and proximal channel. Finally, similar pH monitoring results obtained in both study groups with GERD confirm that pH monitoring is clinically important for diagnosing of acid GER but not for differential diagnosis for between primary and secondary GER patients. This support the necessity of early implementation of complex differential diagnosis that enables to distinguish the causes of primary GER from the causes of GER secondary to FA. This causal differentiation leads to necessity of defining proper treatment strategy. It also influences the efficacy of treatment and natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children and the young.

S- Editor Liu Y L- Editor Rampone B E- Editor Liu Y

| 1. | Shepherd RW, Wren J, Evans S, Lander M, Ong TH. Gastroesophageal reflux in children. Clinical profile, course and outcome with active therapy in 126 cases. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1987;26:55-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Semeniuk J. Ethiopathogenic role of gastro-oesophageal reflux in developing of clinical symptoms in children [dissertation]. Medical University of Białystok. 1990;3. |

| 3. | Herbst JJ. Gastroesophageal reflux. J Pediatr. 1981;98:859-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nelson HS. Gastroesophageal reflux and pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984;73:547-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Herbst JJ, Book LS, Bray PF. Gastroesophageal reflux in the "near miss" sudden infant death syndrome. J Pediatr. 1978;92:73-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hermier M, Descos B. [Gastroesophageal reflux and respiratory manifestations]. Pediatrie. 1983;38:125-135. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Malfertheiner P, Hallerbäck B. Clinical manifestations and complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:346-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Semeniuk J, Kaczmarski M. Gastroesophageal reflux in children and adolescents. clinical aspects with special respect to food hypersensitivity. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51:327-335. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Semeniuk J, Wasilewska J, Kaczmarski M, Lebensztejn D. Non-typical manifestation of gastroesophageal reflux in children. Med Sci Monit. 1998;4:1122-1130. |

| 10. | Iacono G, Carroccio A, Cavataio F, Montalto G, Kazmierska I, Lorello D, Soresi M, Notarbartolo A. Gastroesophageal reflux and cow's milk allergy in infants: a prospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;97:822-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Milocco C, Torre G, Ventura A. Gastro-oesophageal reflux and cows' milk protein allergy. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:183-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Semeniuk J, Kaczmarski M, Nowowiejska B, Białokoz I, Lebensztejn D. Food allergy as the causa of gastroesophageal reflux in the youngest children. Pediatr Pol. 2000;10:793-802. |

| 13. | Salvatore S, Vandenplas Y. Gastroesophageal reflux and cow milk allergy: is there a link? Pediatrics. 2002;110:972-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | A standardized protocol for the methodology of esophageal pH monitoring and interpretation of the data for the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux. Working Group of the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1992;14:467-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vandenplas Y, Loeb H. The interpretation of oesophageal pH monitoring data. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;149:598-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vandenplas Y, Goyvaerts H, Helven R, Sacre L. Gastroesophageal reflux, as measured by 24-hour pH monitoring, in 509 healthy infants screened for risk of sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics. 1991;88:834-840. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Vandenplas Y, Sacré-Smits L. Continuous 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring in 285 asymptomatic infants 0-15 months old. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;6:220-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Arana A, Bagucka B, Hauser B, Hegar B, Urbain D, Kaufman L, Vandenplas Y. PH monitoring in the distal and proximal esophagus in symptomatic infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bagucka B, Badriul H, Vandemaele K, Troch E, Vandenplas Y. Normal ranges of continuous pH monitoring in the proximal esophagus. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31:244-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Semeniuk J, Kaczmarski M, Krasnow A, Sidor K, Matuszewska E, Daniluk U. Dual simultaneous esophageal pH monitoring in infants with gastroesophageal reflux. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2003;14:405-409. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kaczmarski M. Food allergy and intolerance. Milk, sugars, soya. Sanmedia, Warszawa. 1993;7-10. |

| 22. | Staiano A, Troncone R, Simeone D, Mayer M, Finelli E, Cella A, Auricchio S. Differentiation of cows' milk intolerance and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73:439-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Iacono G, Carroccio A, Cavataio F, Montalto G, Lorello D, Kazmierska I, Soresi M. IgG anti-betalactoglobulin (betalactotest): its usefulness in the diagnosis of cow's milk allergy. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1995;27:355-360. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Cavataio F, Iacono G, Montalto G, Soresi M, Tumminello M, Campagna P, Notarbartolo A, Carroccio A. Gastroesophageal reflux associated with cow's milk allergy in infants: which diagnostic examinations are useful? Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1215-1220. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kaczmarski M. The stand of Polish Group of experts to food allergy and intolerance. Polish Society for Alergology, Symposium 1, Medical Convention Periodical, Unimed. 1997;1:21-31, 39-67. |

| 26. | Matuszewska E, Kaczmarski M, Semeniuk J. Oral challenge tests in diagnostics of ford allergy and intolerance. Ped Współczesna Gastroenterol Hepatol i Żywienie Dziecka. 2000;2-4:239-243. |

| 27. | Strobel CT, Byrne WJ, Ament ME, Euler AR. Correlation of esophageal lengths in children with height: application to the Tuttle test without prior esophageal manometry. J Pediatr. 1979;94:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | McCauley RG, Darling DB, Leonidas JC, Schwartz AM. Gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children: a useful classification and reliable physiologic technique for its demonstration. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978;130:47-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Thor P, Herman R, Plebankiewicz S, Bogdał J. Esophageal manometry and pH-metry in gastroesophageal reflux disease; their role in preoperative evaluation. Acta Endosc Pol. 1994;6:167-173. |

| 30. | Kiljander TO, Laitinen JO. The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adult asthmatics. Chest. 2004;126:1490-1494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gustafsson PM, Tibbling L. 24-hour oesophageal two-level pH monitoring in healthy children and adolescents. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988;23:91-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Cucchiara S, Santamaria F, Minella R, Alfieri E, Scoppa A, Calabrese F, Franco MT, Rea B, Salvia G. Simultaneous prolonged recordings of proximal and distal intraesophageal pH in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease and respiratory symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1791-1796. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Little JP, Matthews BL, Glock MS, Koufman JA, Reboussin DM, Loughlin CJ, McGuirt WF. Extraesophageal pediatric reflux: 24-hour double-probe pH monitoring of 222 children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1997;169:1-16. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Semeniuk J, Tryniszewska E, Wasilewska J, Kaczmarski M. Food allergy- causal factor of gastroesophageal reflux in children. Terapia. 1998;6:16-19. |

| 35. | Fyderek K, Stopyrowa J, Sładek M. Gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor in different diseases in children. Przegl Lek. 1991;48:385-389. |

| 36. | Zielińska I, Czerwionka-Szaflarska M. The value of pH-metric examination in diagnostics of recurrent bronchitis and pneumonia. Przegl Pediatr. 1999;supp l:52-54. |

| 37. | Cavataio F, Iacono G, Montalto G, Soresi M, Tumminello M, Carroccio A. Clinical and pH-metric characteristics of gastro-oesophageal reflux secondary to cows' milk protein allergy. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75:51-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |