Published online Sep 28, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i36.4897

Revised: June 15, 2007

Accepted: June 18, 2007

Published online: September 28, 2007

AIM: To systematically evaluate the efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection of gastrointestinal smooth muscle tumors (SMTs, including leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma) and to review our preliminary experiences on endoscopic diagnosis of gastrointestinal SMTs.

METHODS: A total of 69 patients with gastrointestinal SMT underwent routine endoscopy in our department. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was also performed in 9 cases of gastrointestinal SMT. The sessile submucosal gastrointestinal SMTs with the base smaller than 2 cm in diameter were resected by “pushing” technique or “grasping and pushing” technique while the pedunculated SMTs were resected by polypectomy. For those SMTs originating from muscularis propria or with the base size ≥ 2 cm, ordinary biopsy technique was performed in tumors with ulcers while the “Digging” technique was performed in those without ulcers.

RESULTS: 54 cases of leiomyoma and 15 cases of leiomyosarcoma were identified. In them, 19 cases of submucosal leiomyoma were resected by “pushing” technique and 10 cases were removed by “grasping and pushing” technique. Three cases pedunculated submucosal leiomyoma were resected by polypectomy. No severe complications developed during or after the procedure. No recurrence was observed. The diagnostic accuracy of ordinary and the “Digging” biopsy technique was 90.0% and 94.1%, respectively.

CONCLUSION: Endoscopic resection is a safe and effective treatment for leiomyomas with the base size ≤ 2 cm. The “digging” biopsy technique would be a good option for histologic diagnosis of SMTs.

- Citation: Zhou XD, Lv NH, Chen HX, Wang CW, Zhu X, Xu P, Chen YX. Endoscopic management of gastrointestinal smooth muscle tumor. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(36): 4897-4902

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i36/4897.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i36.4897

Gastrointestinal smooth muscle tumors (SMTs, including leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma) represent relatively common lesions that are thought to originate from a muscular layer of gastrointestinal tract. They can be found in the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colon[1-3]. The most common symptoms of gastrointestinal SMTs are gastrointestinal bleeding, as a result of overlaying mucosa ulceration, and pain. Other symptoms may include anorexia, dysphagia, obstruction, perforation, or fever[4-6].

Gastrointestinal SMTs are difficult-to-cure gastrointestinal tumors when compared with polyps and the complete surgical resection is still considered to be the most definitive therapy for gastrointestinal SMTs. In recent years, several reports[7-10] suggest that endoscopic treatment of GI submucosal leiomyoma is a valid alternative to invasion surgery. However, these reports cannot provide enough convincing evidence for the efficiency and safety of the treatment they used because lack of enough cases (majority of these reports include only one single case). Meanwhile, the endoscopic resection is inappropriate for leiomyosarcoma and those leiomyomas with either the base ≥ 2 cm in diameter or originating from muscularis propria because of the risk of hemorrhage and perforation[7-10]. Therefore, a safe and efficient therapeutic strategy for endoscopic resection of leiomyoma is worth being explored.

From 1986-2006, more than 100 cases of gastrointestinal submucosal tumors (including leiomyoma) were found and successfully resected under endoscopy in our unit. Enlightened by these cases, we prospectively explored the feasibility, efficacy, and safety for endoscopic removal of leiomyoma. During the last fifteen years, 69 cases of SMTs have undergone the endoscopic examinations and finally proven pathologically at our hospital. Within these, 32 cases of submucosal leiomyoma were successfully removed under endoscopy. The present study evaluated the efficacy and safety of our technique for endoscopic resection of submucosal leiomyoma. Meanwhile, our preliminary experience on diagnosis of SMT based on endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was also reviewed in this study.

From January 1992 to January 2006, 69 cases of SMT were found under endoscopy and identified by further pathological examination at First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China). Of these, 39 were male and 30 were female. The age range was 15-74 (average 45.6) years. All the patients complained of at least one of the GI symptoms such as gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal pain, anorexia, and dysphagia, which could be attributed to the SMT. Written informed consent was obtained from every patient. The locations and types of these SMTs are presented in Table 1. Under immunohistochemical staining, all these SMTs were positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA) but negative for CD117 (C-kit).

| Location | Leiomyoma | Leiomyosarcoma | |

| Esophageal | Upper | 4 | 0 |

| Middle | 11 | 0 | |

| Lower | 13 | 0 | |

| Stomach | Cadiac | 4 | 0 |

| Fornix | 4 | 6 | |

| Corpus | 5 | 4 | |

| Antrum | 6 | 2 | |

| Duodenum | Bulb | 2 | 1 |

| Descending part | 1 | 2 | |

| Colon | Ascending colon | 2 | 0 |

| Transverse colon | 2 | 0 | |

| Total | 54 | 15 |

All the patients underwent routine gastrointestinal endoscopy (Olympus GF/CF 230 or 240I; PENTAX-2901) to assess the location, appearance, extent, and overlaying mucosa integrity of the SMTs. After February 2005, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS, Olympus GF-UM20) was utilized to detect the size and shape, echodensity, and the originating layer of tumor in the wall structure. Interpretation was based on the five-layer structure of the wall. For those SMTs with overlaying mucosa ulcerations, the biopsy specimens were obtained from the bottom of the ulcer. The “digging” biopsy technique was employed for those protrusive lesions without overlaying mucosa ulceration but with the base ≥ 2 cm in diameter or originating from muscularis propria.

The criterion for choice of therapy was: (1) the pedunculated submucosal SMTs with the base smaller than 2 cm in diameter were resected by polypectomy; (2) the sessile submucosal SMTs with the base smaller than 2 cm in diameter were removed using a “pushing” technique or “grasping and pushing” technique; (3) those SMTs pathologically identified malignant, originated from muscularis propria, or with the base size ≥ 2 cm were surgically resected. Histopathologic features of both endoscopically and surgically removed SMTs were reviewed by two experienced histopathologists. In addition, all specimens underwent immunostaining of SMA and CD117 (C-kit). Histological examination was also used to determine whether the tumor was removed completely.

After endoscopic removal of SMT, patients were required to remain in the hospital for at least 2 d. Bed rest was necessary for the patients with colonic SMT. Patients with upper gastrointestinal SMTs fasted for 2 d. Endoscopy was performed one week after resection to assess healing and examine hemorrhagic signs such as exposed vessels. Follow-up endoscopic examination was performed every six months for the first year and annually thereafter. Each case was followed up by endoscopic examination for 1-2 years.

The technique for the resection of pedunculated SMTs was the same as initiated for epithelial polyps. In brief, the snare was placed around the stalk of the SMT, tightened and lifted toward the cavity of the GI tract. The snare was tightened gradually and the SMT was resected by coagulation current.

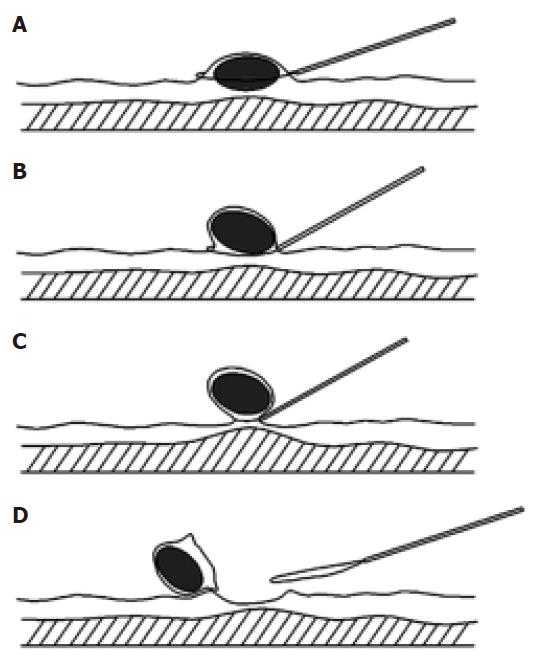

For a sessile SMT, the snare was placed around the lesion (Figure 1). The head (gastroscopy) or anal (colonoscopy) side of the lesion was pushed by the insulated cannula of snare to form a semipedunculation. The snare was tightened gradually at the top of the semipedunculation and total SMT was captured and then resected completely by a high-frequency electrosurgical current.

This technique was performed with a double channel endoscopy. In brief, a polypectomy snare inserted through the accessory channel was first placed around the submucosal tumor. The body of the tumor was lifted by a grasping forceps inserted from the other channel to form a semipedunculation. The submucosal tumor was then captured by tightening the snare gradually at the top of the semipedunculation. Finally, the tumor was resected by a high-frequency electrosurgical current.

Initially, a biopsy forceps was used to open a hole in the overlaying mucosa leaving the SMT exposed. At least 4 biopsy specimens were then obtained from the exposed SMT.

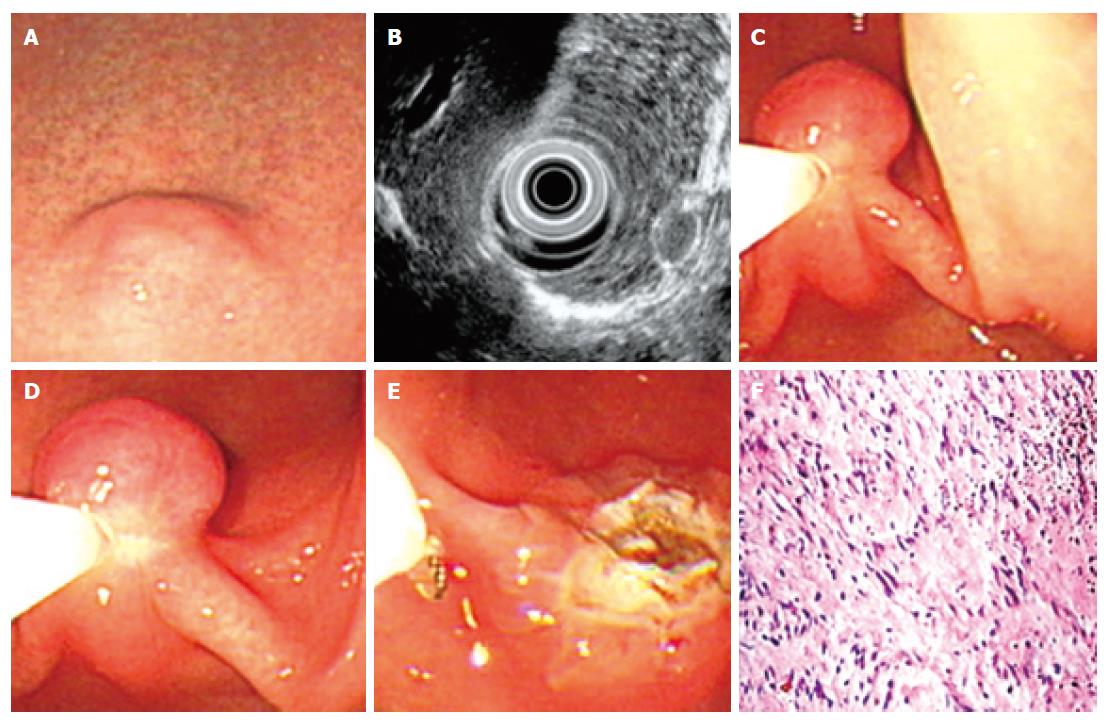

During the last 15 years, 54 cases of leiomyoma were identified at our hospital. Under endoscopy, most leiomyomas appeared as a red and smooth sessile protrusions with normal overlaying mucosa. Only 3 cases of leiomyoma were shown as pedunculated lesions. The esophagus was the most frequent site (51.8%) for leiomyoma (Table 1), followed by stomach (35.2%), colon (7.4%), and duodena (5.6%). No correlation was found between the occurrence and either age or gender in this study. The average base size of leiomyomas measured under endoscopy was 1.2 ± 0.2 cm (standard deviation, SD). The smallest one was 0.8 cm in diameter while the largest was 3.4 cm in diameter. From February 2005 to January 2006, EUS was performed in 6 cases of leiomyoma. All these leiomyoma were shown as an echolucent mass with sharp margin and originating from muscularis mucosa (3 cases) or muscularis propria (3 cases) of gastrointestinal tract. Average size of these 6 cases of leiomyomas measured under EUS was 1.1 ± 0.3 cm (SD).

Among the above-mentioned 54 cases of leiomyoma, 19 cases of submucosal leiomyoma were resected by “pushing” technique (Figure 2) while 10 cases were removed by “grasping and pushing” technique (Table 2). Only 3 cases pedunculated submucosal leiomyoma were resected by polypectomy (Table 2). All these resected leiomyomas were confirmed by the following histopathologic examination. Immediate endoscopic observation after all these resections showed a 1.2-1.5 cm cauterization burn without other abnormalities. No complications such as perforation and hemorrhage developed during or after the procedure in most of these patients. Oozy bleeding occurred in 4 patients and easily controlled after epinephrine or thrombin spraying. After a follow-up period of one to two years with repeated endoscopy, no recurrence was found.

| Location | Pushing | Pushing andgrasping | Polypectomy | |

| Esophageal | Upper | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Middle | 5 | 2 | 0 | |

| Lower | 3 | 3 | 1 | |

| Stomach | Cadiac | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Fornix | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Corpus | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Antrum | 3 | 0 | 1 | |

| Duodenum | Bulb | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Descending part | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Colon | Ascending colon | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Transverse colon | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 19 | 10 | 3 |

Among the remaining 22 cases of leiomyoma with the base size ≥ 2 cm or originating in muscularis propria, 9 cases were observed with occurrence of overlaying mucosa ulceration. Of these, 8 cases (88.9%) were confirmed pathologically by obtaining biopsy specimens from the bottom of the ulcer while one case failed to report by this method. For those leiomyomas without ulcer, 12 cases (92.3%) were confirmed by “digging” biopsy while only one case (7.7%) failed to report by this method. All 22 cases of leiomyoma were successfully removed by surgery.

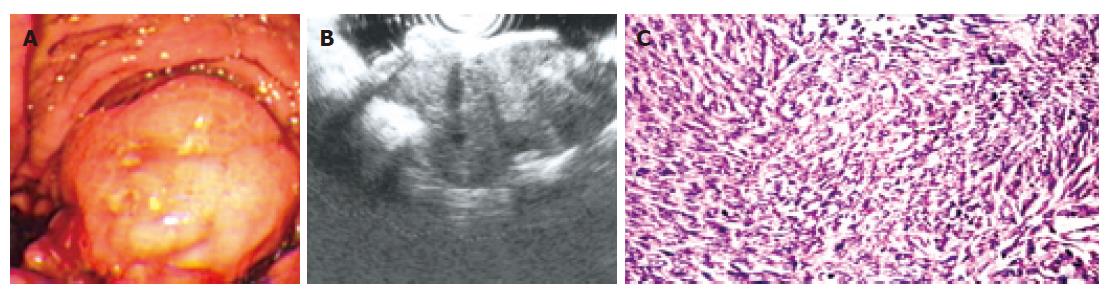

In this study, 15 cases of leiomyosarcoma were surgically resected and confirmed by following histopathologic examination. No correlation was found between the occurrence and either age or gender in this study. Of these, endoscopy revealed the lesion as an intraluminal protuberant tumour with ulcer (Figure 3A) in 7 cases and without ulcer in 4 cases. Another 4 cases appeared as an ulcer alone. The occurrence frequency of ulcer in leiomyosarcoma is 73.3% (11/15), which is obviously higher than that in leiomyoma (16.7%, 9/54). Leiomyosarcoma were observed in stomach (80.0%) and duodena (20.0%). The average base size of leiomyosarcoma measured under endoscopy was 6.8 ± 2.3 cm (SD). A significant difference was found between the base size of leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma (P < 0.001, non-paired t test). From February 2005 to January 2006, three cases of leiomyosarcoma underwent EUS examination. All three tumours were found to arise from the fourth echo poor layer (muscularis propria); EUS showed that one gastric tumour disrupted all the wall layers. The tumour echostructure and margins were inhomogeneous and irregular in all three cases (Figure 3B).

In those 11 cases of leiomyosarcoma with occurrence of ulcer, 10 cases (90.9%) were comfirmed pathologically by obtained biopsy at the bottom of the ulcer. One case failed to report by this technique and finally confirmed after surgical resection. The remaining 4 cases of leio-myosarcoma without ulcer were confirmed by “digging” biopsy.

To resect submucosal SMT by endoscopy, it is crucial to determine the originating layer of the lesion. If the tumor arises from muscularis propria, complete resection should be avoided because of the risk of perforation[7-12]. Recently, EUS was considered to be very helpful in determining the size, consistency, extension of submucosal tumors, and the layer from which tumors originate[12-15]. Therefore, the assistance of EUS greatly increases the safety of endoscopic resection of submucosal SMTs[9,12,13]. In our unit, EUS were employed in evaluating 6 cases of leiomyoma. Of these, three cases were found originating from muscularis mucosa, and then were resected completely under endoscopy. Another 3 cases, originating from muscularis propria, were successfully performed via surgical resection. However, the EUS were equipped in our department only after January 2005. Before 2005, we determined the location of submucosal tumor through detecting the mobility of tumor by closed biopsy forceps. In brief, if the forceps pushed the tumor to slide under mucosa, it suggested that the tumor originated superficially in muscularis mucosa and was resectable by means of endoscopy. Whereas, an immobile tumor revealed that the tumor had its roots in muscularis propria and could not be removed by endoscopic resection. Although we admit that this criterion is somewhat imprecise, all submucosal leiomyomas (26 cases) determined by this method were successfully performed endoscopic resections, no perforations or severe bleeding occurred after resection. In addition, in those 6 cases examined by EUS, the conclusions drawn by this method fit well with those by EUS. All these were enough to prove the reliability of our method.

The “Pushing” technique has been employed by our group for resection for various gastrointestinal submucosal tumors including leiomyoma, fibroma, lipoma, carcinoid. All these submucosal tumors were successfully resected, with the exception of one case of fibroma, which underwent severe bleeding after resection. In the present study, 19 cases of leiomyoma were successfully and safely removed by the “pushing” technique. No recurrence was observed after 1-2 years follow-up. The crucial step for this technique is the movement of pushing. Because of the pushing by insulated cannula of snare, a semipedunculation forms and then the whole body of the tumor is easily captured by pre-placed snare. This ensures that the tumor can be resected completely. Meanwhile, because the tumor body is lifted toward cavity before cauterization and the line of resection is at the bottom of the tumor body and the top of the semipedunculation, the muscularis propria has already separated from the place of cauterization and then will not be injured by the high-frequency electrosurgical current. Additionally, to minimize potential severe hemorrhage and perforation, we avoid undergoing endoscopic resection of those lesions with the base ≥ 2 cm. All these fully demonstrate the efficiency and safety of the “pushing” technique utilized. When compared with other techniques such as En Bloc[9,15-17], the pushing technique is much easier to be operated and takes less time.

The En bloc technique has been used by several groups for endoscopic resection of submucosal SMTs[9,15-17]. By our understanding, there are at least two advantages for this technique. First, this technique contains an important step-injection of the saline solution into the submucosa, which is to separate the line of resection from muscularis propria and then prevent the injury of muscle layer. This step greatly increases the safety of the operation. Second, the removed tumors can be easily captured for further histological examination. However, we consider that this technique also has the shortcomings of complicated operation and time-consuming. In fact, it is a tough job for an endoscopist to inject the solution exactly into the base of the leiomyoma without injuring the wall of the gastrointestinal tract. Furthermore, injection of saline may make the margin of the lesion unclear. To overcome these problems, we tried to explore the possibility of deleting the procedure of saline injection. Normally, 19.4 mm grasping forceps can easily grasp the body of tumor and lift it up towards the cavity of the gastrointestinal tract to form a pseudo-pedunculation. In fact, this step has already separated the tumor from muscularis propria and then is enough to prevent the injury of muscle layer when the captured tumor is removed by pre-placed snare. In some cases, the surface of the tumor is too slippery and difficult to grasp. To solve this problem, we first grasped the overlaying mucosa, and then pushed the tumor by insulated cannula of snare to form a semipedunculation, which also prevented the injury of muscularis propria when captured tumors were removed by high-frequency electrosurgical current. In the last 15 years, 10 cases of leiomyoma have been safely removed in our department by using this “grasping and pushing” technique. No recurrence was observed after 1-2 years follow-up. All these fully support the efficiency and safety of the grasping and pushing technique we utilized.

For those SMTs with the base size ≥ 2 cm and/or originating in muscularis propria, to differentiate malignant from benign is crucial for further treatment. Histological diagnosis is necessary not only to ascertain whether a lesion is benign or malignant (usually larger lesions with irregular borders, inhomogeneous areas, or eroded surfaces), but also to detect smaller lesions without malignant morphologic features. In recent years, several methods have been developed for this histological diagnosis. Matsui et al[18] have described a biopsy technique-endoscopic ultrosonography-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (EUS-FNAB). In this technique, the biopsy materials are obtained from a needle, which is inserted into the lesions guided by EUS. Open biopsy, developed by Kojima et al[9], is another effective biopsy technique for gastrointestinal submucosal lesions. In this technique, the covering mucosa is resected to expose the tumor and then several tissues are obtained by ordinary forceps at the bottom of the artificial ulcer. The techniques we used in this study were the “digging” and ordinary biopsy techniques. In order to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of these two techniques, we selected those cases which were finally removed by surgery. In our series, the diagnostic accuracy of “digging” biopsy is 94.1% for those SMTs without ulcer (leiomyoma: 92.3%; leiomysarcoma: 100%). This result is very close to the above-mentioned two techniques, but the “digging” biopsy is much easier and cheaper than EUS-FNAB and open biopsy. In this series, no severe hemorrhage developed after the “digging” biopsy. In addition, the diagnostic accuracy of ordinary biopsy in the SMTs with ulcer is 90.0%, similar to that of “digging” biopsy.

Although EUS is very helpful in deciding the technique for endoscopic resection of submucosal SMTs, it is difficult to differentiate the malignant from benign SMTs by means of EUS unless there is local extension or metastasis, because no significant difference has been found between malignant and benign lesions with regard to homogeneity of internal echo pattern or marginal echo pattern[3,19,20]. However, EUS is considered to be reliable in predicting the potential malignancy of SCTs[3]. The three most predictive EUS features described by Palazzo et al[3] are irregular margins, cystic spaces, and lymph nodes with a malignant patterns. Palazzo et al[3] concluded that (1) the presence of at least one of these criteria had a sensitivity of 91%, a specificity of 88%, a positive predictive value of 83%, and a negative predictive value of 94% for potential malignancy; (2) a combination of two of these three criteria had a positive predictive value and specificity of 100%; (3) tumors of 30 mm or less, with regular extraluminal margins and a homogeneous pattern, are likely to be benign. Our series also support predictive EUS features although only 6 cases of leiomyoma and 3 cases of leiomyosarcoma were investigated.

In conclusion, endoscopic resection is a safe and effective therapy for submucosal leiomyoma with the base size ≤ 2 cm. The guidance of EUS greatly increases the safety of endscopic resection of submucosal leiomyoma. The “digging” biopsy technique would be a good option for the histologic diagnosis of SMT.

Gastrointestinal smooth muscle tumors (SMTs, including leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma) represent relatively common lesions. The complete surgical resection was considered to be the most definitive therapy for SMTs in the past. In recent years, some researchers reported that endoscopic treatment of GI submucosal leiomyoma is a valid alternative to invasion surgery. However, they failed to provide enough convincing evidences for the efficiency and safety of the treatment they used because lack of enough cases.

In the last few decades, gastrointestinal endoscopy has been widely used in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases, it is very important to elucidate the efficiency and safety of endoscopic treatment of SMTs.

The authors revealed that endoscopic treatment of SMTs is efficient and safe through a prospective research with many cases. Meanwhile, the “Pushing” technique and “Grasping and pushing” technique were put forward and analyzed.

The current study will guide the clinical application of endoscopic treatment of SMTs.

This paper may show us endoscopic management of smooth muscle tumor in a single hospital for more than 10 years. However, this study is only a descriptive study of the experienced cases. The authors should consider again the novel findings obtained from the experienced cases.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Li M E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Esophageal stromal tumors: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 17 cases and comparison with esophageal leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:211-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chak A, Canto MI, Rösch T, Dittler HJ, Hawes RH, Tio TL, Lightdale CJ, Boyce HW, Scheiman J, Carpenter SL. Endosonographic differentiation of benign and malignant stromal cell tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:468-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Palazzo L, Landi B, Cellier C, Cuillerier E, Roseau G, Barbier JP. Endosonographic features predictive of benign and malignant gastrointestinal stromal cell tumours. Gut. 2000;46:88-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tricarico A, Cione G, Sozio M, Di Palo P, Bottino V, Martino A, Tricarico T, Falco P. Digestive hemorrhages of obscure origin. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:711-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Campbell F, Bogomoletz WV, Williams GT. Tumours of the oesophagus and stomach. Diagnostic histopathology of tumours. London: Churchill Livingstone 1995; 193-242 PMCid: PMC1135872. |

| 6. | Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR. Gastrointestinal stromal (smooth muscle) tumours. Gastrointestinal and oesophageal pathology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone 1995; 727-739. |

| 7. | Inoue H, Kawano T, Tani M, Takeshita K, Iwai T. Endoscopic mucosal resection using a cap: techniques for use and preventing perforation. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13:477-480. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Yu JP, Luo HS, Wang XZ. Endoscopic treatment of submucosal lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy. 1992;24:190-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kojima T, Takahashi H, Parra-Blanco A, Kohsen K, Fujita R. Diagnosis of submucosal tumor of the upper GI tract by endoscopic resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:516-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee IL, Lin PY, Tung SY, Shen CH, Wei KL, Wu CS. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of intraluminal gastric subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1024-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chow WH, Kwan WK, Ng WF. Endoscopic removal of leiomyoma of the colon. Hong Kong Med J. 1997;3:325-327. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Sun S, Wang M, Sun S. Use of endoscopic ultrasound-guided injection in endoscopic resection of solid submucosal tumors. Endoscopy. 2002;34:82-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Waxman I, Saitoh Y, Raju GS, Watari J, Yokota K, Reeves AL, Kohgo Y. High-frequency probe EUS-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection: a therapeutic strategy for submucosal tumors of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:44-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Oğuz D, Filik L, Parlak E, Dişibeyaz S, Ciçek B, Kaçar S, Aydoğ G, Sahin B. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography in upper gastrointestinal submucosal lesions. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2004;15:82-85. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hunt GC, Rader AE, Faigel DO. A comparison of EUS features between CD-117 positive GI stromal tumors and CD-117 negative GI spindle cell tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:469-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Higaki S, Hashimoto S, Harada K, Nohara H, Saito Y, Gondo T, Okita K. Long-term follow-up of large flat colorectal tumors resected endoscopically. Endoscopy. 2003;35:845-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yamamoto H, Kawata H, Sunada K, Sasaki A, Nakazawa K, Miyata T, Sekine Y, Yano T, Satoh K, Ido K. Successful en-bloc resection of large superficial tumors in the stomach and colon using sodium hyaluronate and small-caliber-tip transparent hood. Endoscopy. 2003;35:690-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Matsui M, Goto H, Niwa Y, Arisawa T, Hirooka Y, Hayakawa T. Preliminary results of fine needle aspiration biopsy histology in upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. Endoscopy. 1998;30:750-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rösch T, Lorenz R, Dancygier H, von Wickert A, Classen M. Endosonographic diagnosis of submucosal upper gastrointestinal tract tumors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sotoudehmanesh R, Ghafoori A, Mikaeli J, Tavangar SM, Moghaddam HM. Esophageal leiomyomatosis diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound. Endoscopy. 2005;37:281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |