Published online Sep 7, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i33.4514

Revised: January 25, 2007

Accepted: January 23, 2007

Published online: September 7, 2007

Diffuse intestinal Kaposi's sarcoma shares macroscopic and histopathologic features with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Correct diagnosis may pose a clinical challenge. We describe the case of a young HIV-1-infected African lady without advanced immunodeficiency, who presented with a diffuse spindle cell tumor of the gut. Initial diagnosis was of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor, based on endoscopy and histopathology. Further evaluation revealed evidence for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8) and the diagnosis had to be changed to diffuse intestinal Kaposi’s sarcoma. Antiretroviral triple therapy together with chemotherapy was commenced, and has led to the rapid remission of intestinal lesions. With a background of HIV infection, the presence of HHV8 as the causative agent of Kaposi’s sarcoma should be determined, as distinct treatment is indicated.

- Citation: Zoufaly A, Schmiedel S, Lohse A, van Lunzen J. Intestinal Kaposi’s sarcoma may mimic gastrointestinal stromal tumor in HIV infection. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(33): 4514-4516

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i33/4514.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i33.4514

Diffuse Kaposi’s sarcoma bears a significant morbidity and mortality risk in individuals with HIV infection. It is commonly observed in untreated male homosexual HIV-1-infected individuals and is associated with advanced immune deficiency. Progressive disease is a very rare condition in HIV-infected women[1,2]. In Africa, Kaposi’s sarcoma is one of the most frequently occurring tumors. It exists in epidemic and endemic forms, the latter not being associated with HIV infection[3]. Diagnosis remains a challenge, particularly in a setting where clinical findings could be readily explained by alternative diagnoses, which may be more common.

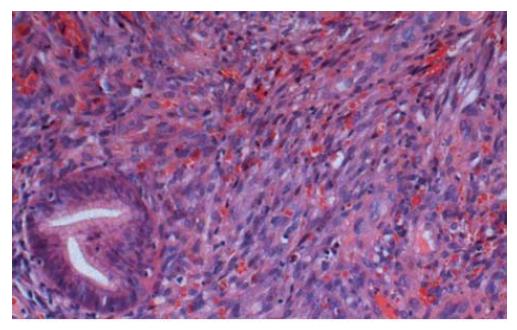

A 29-year-old African woman was admitted to our gastroenterology ward in December 2005 with persisting diffuse abdominal pains and abdominal bloating after returning from Nigeria. She also complained of swelling of the right leg for several months. She was known to be infected with HIV-1 and receiving no specific therapy because of only mild immunodeficiency (absolute CD4 count 304/mm3, CD4/CD8 ratio 0.94 on admission) despite a high viral load (180 000 HIV-1-RNA/mL). Previous history included diabetes, hypothyroidism and arterial hypertension. On examination, mild swelling of the right leg was observed. Ultrasound suggested a deep venous thrombosis, which was treated initially with low molecular weight heparins. Pathologic findings in the blood test included normocytic anaemia, mild thrombocytosis and slightly raised LDH, amylase and lipase levels. Abdominal CT scan was normal. On endoscopy of the upper GI tract, candida oesophagitis, diffuse, non-erosive gastritis and duodenitis with several ulcerous lesions were observed (Figure 1). Colonoscopy revealed diffuse polypoid lesions throughout the entire colon, with aphtous lesions in the sigma (Figure 2). Histopathology showed ulcerative duodenitis. No evidence for T. whippeli, fungi, giardiasis, CMV or HSV infection was found in biopsies. However, a mesenchymal CD34-positive and weakly CD117-positive, SM actin-negative stroma-like tumor was found in all biopsies from the colon. The nuclear proliferation antigen Ki67 was positive in 10%-20% of tumor cells. The diagnosis of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) was made by the pathologist. Figure 3 shows spindle cell proliferations in colon biopsies involving the lamina propria; these are readily observed in gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

Because of the diffuse involvement of the entire GI tract, the histological diagnosis was questioned and the patient was readmitted for further biopsies. The possibility of an atypical clinical presentation of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor due to underlying HIV infection was discussed.

In the meantime, her clinical condition had deteriorated with marked weight loss and persistent abdominal pain. Examination of her right foot revealed several tumour-like lesions, which were diagnosed as dermatitis exsudativa by a consultant dermatologist, and a skin biopsy was taken. Ultrasound of the persistently swollen right leg revealed an enlarged lymph node in the right groin, but no signs of a DVT.

Again, gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed, showing a macroscopic appearance similar to the previous investigations, and several biopsies were taken. Finally, further histopathologic examination, including HHV-8 staining of these biopsies, now suggested diffuse Kaposi’s sarcoma of the intestine. Retrospective evaluation of the biopsies previously taken from the colon also revealed HHV-8 reactivity.

The diagnosis of diffuse Kaposi’s sarcoma was further supported by the detection of HHV-8 in the skin biopsies as well as in the blood. Antiretroviral combination therapy, including two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and a boosted protease inhibitor together with 2-weekly liposomal Doxorubicin, was commenced. On her last follow-up visit 6 mo later, the abdominal symptoms and swelling of the leg had resolved completely. Endoscopy of the upper and lower intestinal tract showed no further evidence of Kaposi’s sarcoma in the colon, with only small residuals remaining in the duodenum.

GIST and Kaposi’s sarcoma both present as diffuse intestinal lesions with spindle cells, and their diagnosis may be confused because of the presence of CD34-expressing spindle cells with only weak CD117 (c-kit) positivity. Most GISTs show positive immunostaining for CD117 and CD34, but are negative for HHV8. Recent data show the presence of CD117 positivity in up to 56% of Kaposi sarcomas, and overexpression occurs in HHV8-coinfected cells[4]. However, the original cells in Kaposi's sarcoma are of vascular origin, and the presence of human herpesvirus 8 can be found in at least 95% of cases[5]. HHV8 PCR should be performed early to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of Kaposi’s sarcoma, especially in immunodeficient patients, because distinct treatment may be indicated[6].

In HIV-positive patients, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has clearly influenced the occurrence of Kaposi’s sarcoma, and is the most important therapy to stop the progression and improve the prognosis of diffuse disease, as also demonstrated by our case[7]. In individual cases with widespread disease and multiple organ involvement, the use of liposomal anthracyclines may be beneficial for the induction of complete remission[8]. The presence of c-kit positivity may rather warrant the use of a selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor, such as imatinib mesylate. To date, however, clinical experience is limited to a few patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma refractory to conventional therapy[9]. Further studies using this novel therapeutic approach clearly need to be performed.

S- Editor Ma N L- Editor McGowan D E- Editor Liu Y

| 1. | Stebbing J, Sanitt A, Nelson M, Powles T, Gazzard B, Bower M. A prognostic index for AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2006;367:1495-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Krown SE, Testa MA, Huang J. AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: prospective validation of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group staging classification. AIDS Clinical Trials Group Oncology Committee. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:3085-3092. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Antman K, Chang Y. Kaposi's sarcoma. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1027-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 672] [Cited by in RCA: 608] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pantanowitz L, Schwartz EJ, Dezube BJ, Kohler S, Dorfman RF, Tahan SR. C-Kit (CD117) expression in AIDS-related, classic, and African endemic Kaposi sarcoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2005;13:162-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang YM, Bachmann S, Hemmer C, van Lunzen J, von Stemm A, Kern P, Dietrich M, Ziegler R, Waldherr R, Nawroth PP. Vascular origin of Kaposi's sarcoma. Expression of leukocyte adhesion molecule-1, thrombomodulin, and tissue factor. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:51-59. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Miettinen M, Majidi M, Lasota J. Pathology and diagnostic criteria of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): a review. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38 Suppl 5:S39-S51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Martinez V, Caumes E, Gambotti L, Ittah H, Morini JP, Deleuze J, Gorin I, Katlama C, Bricaire F, Dupin N. Remission from Kaposi's sarcoma on HAART is associated with suppression of HIV replication and is independent of protease inhibitor therapy. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1000-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Northfelt DW, Dezube BJ, Thommes JA, Miller BJ, Fischl MA, Friedman-Kien A, Kaplan LD, Du Mond C, Mamelok RD, Henry DH. Pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin versus doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine in the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: results of a randomized phase III clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2445-2451. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Koon HB, Bubley GJ, Pantanowitz L, Masiello D, Smith B, Crosby K, Proper J, Weeden W, Miller TE, Chatis P. Imatinib-induced regression of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:982-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |