Published online Aug 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i30.4112

Revised: June 3, 2007

Accepted: June 9, 2007

Published online: August 14, 2007

AIM: To investigate the hypothesis that duodeno-jejunal dyssynergia existed at the duodeno-jejunal junction.

METHODS: Of 112 patients who complained of epigastric distension and discomfort after meals, we encountered nine patients in whom the duodeno-jejunal junction did not open on duodenal contraction. Seven healthy volunteers were included in the study. A condom which was inserted into the 1st duodenum was filled up to 10 mL with saline in increments of 2 mL and pressure response to duodenal distension was recorded from the duodenum, duodeno-jejunal junction and the jejunum.

RESULTS: In healthy volunteers, duodenal distension with 2 and 4 mL did not produce pressure changes, while 6 and up to 10 mL distension effected significant duodenal pressure increase, duodeno-jejunal junction pressure decrease but no jejunal pressure change. In patients, resting pressure and duodeno-jejunal junction and jejunal pressure response to 2 and 4 mL duodenal distension were similar to those of healthy volunteers. Six and up to 10 mL 1st duodenal distension produced significant duodenal and duodeno-jejunal junction pressure increase and no jejunal pressure change.

CONCLUSION: Duodeno-jejunal junction failed to open on duodenal contraction, a condition we call ‘duodeno-jejunal junction dyssynergia syndrome’ which probably leads to stagnation of chyme in the duodenum and explains patients' manifestations.

- Citation: Shafik A, Shafik IA, Sibai OE, Shafik AA. Duodeno-jejunal junction dyssynergia: Description of a novel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(30): 4112-4116

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i30/4112.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i30.4112

The stomach passes chyme to the duodenum (DD) in jets under the control of physiologic antropyloric mechanisms[1-3]. In addition to the chyme, the DD contents comprise mucosal secretions of the DD mucosa, pancreatic secretions such as pancreatic enzymes, lysolecithin and bicarbonate as well as bile as a composition of bile acids, pigments and bilirubin[4-6]. These DD contents are passed to the jejunum (JJ). During their passage through the DD, they are claimed to be controlled by DD sphincters. In addition to the gastroduodenal pyloric sphincter, other controversial sphincters have been described to exist in the DD[7-9]. One sphincter is alleged to be located at the distal end of the DD bulb and may be responsible for segmental achalasia and megabulb[7]. Another sphincter is said to exist proximal to the ampulla of Vater[8]. The ‘Ochsner muscle’ was described by Ochsner to be found below the ampulla of Vater[9]. All of these sphincters were suggested to delay the passage of chyme through the DD so as to become thoroughly mixed with the biliary and pancreatic secretions. However, these sphincters have as yet not been verified as anatomical entities[10].

A previous study had demonstrated a high- pressure zone at the duodenojejunal junction (DJJ), denoting that the DJJ might act as a physiological sphincter[11]. The DJJ pressure had been demonstrated to diminish on duodenal contraction and increase on jejunal contraction[11]. This effect was suggested to be reflex and mediated through the 'duodeno-jejunal junction inhibitory-' and the 'duodeno-jejunal junction excitatory-'reflexes[11]. The former seems to allow the chyme to pass to the JJ from the DD, and the latter reflex upon jejunal contraction appears to prevent reflux of jejunal contents into the DD.

During our study of the duodenal motile activity of 112 patients who complained of epigastric distension and discomfort after meals, we encountered 9 patients in whom the DJJ did not open on DD contraction. We hypothesized the existence of duodeno-jejunal dyssynergia at the DJJ in these patients. This hypothesis was investigated in the current study.

The study comprised of 9 patients (5 women, 4 men, age 33.6 ± 4.2 years, range 28-37). The main complaint was epigastric distension and discomfort after meals of 6-9 years duration (mean 7.3 ± 1.4). They complained also of occasional nausea and vomiting which was spontaneous and sometimes induced epigastric relief. These symptoms occurred 1-1 ½ h after meals. All of the patients had constipation in the form of infrequent defecation. The patients were medicated by diet regulation as well as gastric antisecretory and prokinetic drugs, but no improvement was achieved.

Physical examination, including neurologic, was normal. The patients had a mean body weight of 63.6 ± 2.1 (range 61-68) kg. Blood count and the results of renal and hepatic function tests and electrocardiography were unremarkable. The patients gave an informed written consent to participate in the study, the details of which and their role in it had been explained to them.

Seven healthy volunteers with a mean age of 34.7 ± 4.3 (range 29-38) years were also included in the study; 4 were women and 3 men. They had no gastro-intestinal manifestations in the past or at the time of enrollment in the study. They gave an informed written consent.

The study was approved by the Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Cairo University Faculty of Medicine.

The pressure response of the DJJ to DD distension was recorded. The subjects had fasted for 12 h. A condom was applied to the distal end of a Ryle stomach tube (8 French, Pharma Plast Int AS/UK 3540, Lynge, Denmark) containing multiple lateral apertures. A string was tied to each end of the condom so as to fashion a high compliance balloon between them. To the distal end of the tube we applied a silver clip for radiologic control. A mechanical puller for automatic tube withdrawal (9021H, Disa, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used. The empty condom and tube were swallowed by the subjects and the condom was directed to lie in the 1st DD. The tube was connected to a strain gauge pressure transducer (Statham, Oxnard, CA, USA).

Simultaneous measurement of the pressure in the DD, DJJ, and JJ was performed by means of a perfused open-ended tube: 1 mm internal diameter and 1.5 mm external diameter. One tube was introduced into each of the DD, DJJ, and JJ and connected to a Statham pressure transducer. The position of this manometric tube was accurately determined under fluoroscopic screening for the purpose of which a silver clip had been applied to the distal end of each tube. The pressure recordings were performed 20 min after tubal positioning so that the gut could have adapted to the presence of the tubes.

The resting (basal) pressure was recorded in the DD, DJJ, and JJ. The condom which was lying in 1st DD was filled in 2 mL increments with normal saline up to 10 mL, and the pressures in the DD, DJJ, and JJ were recorded. The condom was then emptied and managed to lie successively in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th DD. In each of these sites the condom was filled again in increments of 2 mL of normal saline and up to 10 mL, and the pressures in the DD, DJJ, and JJ were registered. We did not exceed the saline fillings of the condom beyond 10 mL for fear of duodenal injury.

To ensure reproducibility of the results, the aforementioned recordings were repeated at least twice in the individual subject and the mean value was calculated. The results were adapted statistically using the Student’s t test, and values were given as mean ± standard deviation. Differences assumed significance at P < 0.05.

Adverse side effects were not encountered during or after performance of the tests, which were completed in all the subjects.

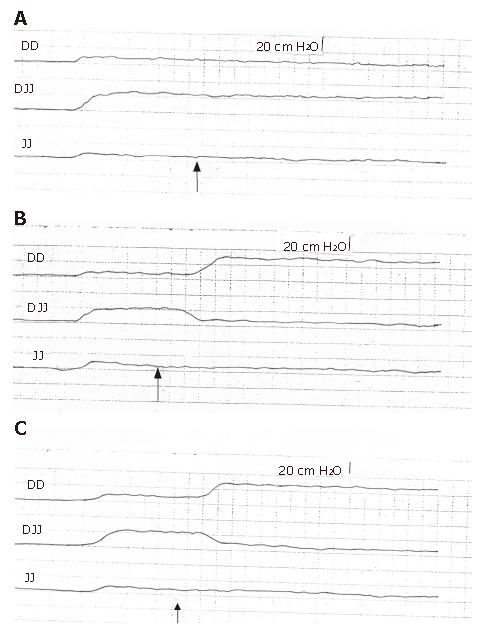

The mean resting (basal) pressure in the 1st DD was 8.3 ± 1.1, DJJ 17.5 ± 2.9, and in the JJ 8.2 ±1.1 cm H2O (Figure 1A, Table 1). The 2nd, 3rd, and 4th DD showed no significant pressure difference against the 1st DD (P > 0.05). DD distension with 2 and 4 mL of normal saline did not effect significant pressure changes in the DD, DJJ, and JJ (P > 0.05, Figure 1A). Six mL balloon distension of the DD produced significant increase of DD pressure to a mean of 26.4 ± 5.9 cm H2O (P < 0.01), a decrease of DJJ pressures to a mean of 6.9 ± 1.1 cm H2O (P < 0.01) and no significant change in the JJ pressure (P > 0.05; Figure 1B) and the balloon was dispelled to the JJ. The pressure in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th DD did not significantly change from the resting pressure. DD balloon distension with 8 and 10 mL of saline produced pressure changes in the DD, DJJ, and JJ similar to those of the 6 mL balloon distension (P > 0.05; Figure 1C). When we transferred the collapsed balloon individually to the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th DD and distended the balloon as aforementioned, we obtained results similar to those measured in the 1st DD with no significant difference (P > 0.05).

| Pressure (cm H2O) | ||||||||||||

| Distensionvolume(mL) | Volunteers | Patients | ||||||||||

| DD | DJJ | JJ | DD | DJJ | JJ | |||||||

| Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | Mean | Range | |

| 0 (basal) | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 8-12 | 17.3 ± 2.9 | 15-23 | 8.2 ± 1.1 | 6-10 | 7.9 ± 1.1 | 7-11 | 18.2 ± 2.8 | 16-25 | 8.4 ± 1.1 | 6-11 |

| 2 | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 7-12 | 16.9 ± 2.8 | 14-22 | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 5-10 | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 8-11 | 17.9 ± 2.7 | 15-24 | 8.2 ± 1.1 | 5-10 |

| 6 | 26.4 ± 5.9b | 20-32 | 6.9 ± 1.1b | 5-9 | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 5-9 | 24.2 ± 5.2b | 18-29 | 33.4 ± 4.8a | 26-38 | 8.1 ± 1.1 | 5-10 |

| 10 | 25.9 ± 5.8b | 21-30 | 6.8 ± 1.1b | 5-10 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 6-10 | 25.4 ± 5.2b | 20-32 | 32.9 ± 4.7a | 25-36 | 7.9 ± 1.1 | 4-9 |

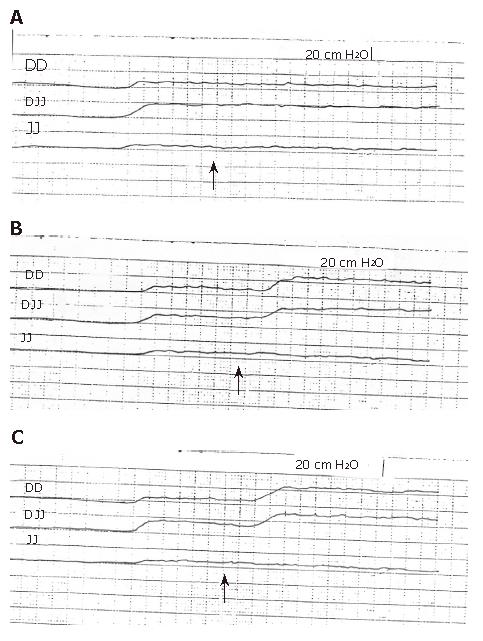

The mean resting pressure in the 1st DD, DJJ, and JJ did not differ significantly from that of the healthy volunteers (P > 0.05); it recorded 7.9 ± 1.1 for the 1st DD, 18.2 ± 2.8 for the DJJ and 8.4 ± 1.1 cm H2O for the JJ (Table 1, Figure 2A). The resting pressures in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th DD were similar to that of the 1st DD (P > 0.05). DD distension with 2 and 4 mL of normal saline did not produce significant pressure changes in the DD, DJJ, and JJ (Table 1). Six mL DD balloon distension resulted in a significant increase of the 1st DD pressure to a mean of 24.2 ± 5.2 cm H2O (P > 0.01), an increase of DJJ pressure to a mean of 33.4 ± 4.8 cm H2O (P < 0.05), but no significant JJ pressure changes (P > 0.05; Table 1; Figure 2B); the balloon in the 1st DD moved to the 3rd DD. DD balloon distension with 8 and 10 mL of saline produced pressure changes in the DD, DJJ, and in the JJ similar to those produced by the 6 mL balloon distension (P > 0.05, Table 1, Figure 2C). When the balloon in the 1st DD was emptied and transferred to the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th DD, refilled with normal saline as aforementioned, and when the test was repeated in a fashion similar to the one performed in the 1st DD, we obtained similar results with no significant difference (P > 0.05).

A recent study has demonstrated the presence of a high- pressure zone at the DJJ with a mean length of 1.6 cm[11]. This zone exists between 2 lower pressure zones: the DD proximally and the JJ distally. It presumably acts as a physiologic sphincter that seems to be responsible for delaying the passage of chyme from the DD to the JJ; this delay has been previously reported by investigators[7-9].

The stomach contents are delivered to the DD in jets owing to the intermittent opening of the pyloric sphincter[12]. The chyme boli received from the stomach presumably accumulate in the DD. When they attain a certain volume that distends the DD, a duodeno-jejunal junction inhibitory reflex seems to be evoked which effects DD contraction and DJJ relaxation with a resulting expulsion of the DD contents into the JJ[11].

The possible existence of a physiologic sphincter at the DJJ apparently regulates the flow of chyme from the DD to the JJ[11]. Thus, it seems that the DJJ acts to retain momentarily the DD contents within the DD, supposedly to allow the time necessary for mixing the chyme with the duodenal biliary and pancreatic secretions that are poured into the DD. When this secretions-containing chyme passes to and distends the JJ, the duodeno-jejunal excitatory reflex is apparently evoked with a resulting DJJ contraction[11]. This reflex seems to act to seal the DJJ upon JJ contraction, probably to avoid reflux of JJ contents back into the DD.

The DJJ pressure response to rising DD or JJ pressure as well as the presence of a high pressure zone at the DJJ would `postulate the existence of a physiologic sphincter at the DJJ[11]. This sphincter seems to dilate on DD contraction, and to contract on JJ contraction[11]. The response of the DJJ to DD or JJ contraction was postulated to be reflex and mediated through the ‘duodeno-jejunal junction reflex’[11].

The results of the current study have shown that the DJJ did not open upon DD distension with small volumes, thereby presumably retaining the DD contents in the DD for the biliary and pancreatic secretions to act upon. The distended condom was considered to represent a food bolus. In the healthy volunteers the study demonstrated that the 1st DD distension to a certain level affected an increase of the DD pressure, a DJJ opening and the expulsion of the balloon to the JJ. This is in contrast to the patients, in whom DD balloon distension to a degree similar to that of the volunteers produced balloon expulsion to only the 3rd DD; this effect seems to be due to the DJJ failing to open on DD distension. We call the failure of the DJJ to open on DD contraction the ‘duodeno-jejunal junction dyssynergia’ (DJJD). This condition had been encountered in 9 of 112 (8.03%) patients who complained of epigastric distension and discomfort after meals.

The failure of the DJJ to open on DD distension might explain the cause of the patients’ symptoms. It appears that chyme, after crossing the pyloric sphincter to the DD, gets obstructed at the DJJ. The chyme appears to be retained in the DD and seems to be responsible for the feeling of the epigastric distension and discomfort and vomiting that might follow the meals. We did not specify the pressure level that would initiate the opening of the DJJ. Probably a greater degree of DD distension could have provided the answer, but we refrained from excess balloon distension for fear of duodenal injury.

The question that needs to be discussed now is: what causes the ‘duodeno-jejunal junction dyssynergia syndrome’ (DJJDS) to develop? Under normal physiologic conditions, the DJJ relaxes on DD contraction, an action mediated through the ‘duodeno-jejunal junction inhibitory reflex’[11]. It appears that DD distension to a certain degree stimulates the mechanoreceptors in the DD wall and the nerve impulses reach the spinal cord. Impulses from the spinal cord supposedly reach the DJJ and effect its relaxation. The DJJDS seems to result from a neurogenic or myogenic defect or a disorder of the neuromuscular transmission. Although the patients were neurologically free, yet further investigations into the pathogenesis of the DJJDS seem to be indicated.

Patients with DJJDS have to be differentiated from patients with functional dyspepsia (FD). The latter patients complain of persistent or recurrent pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen without evidence of organic disease likely to explain the symptoms[13]. The symptoms have been related to visceral hypersensitivity, impaired gastric accommodation and psychological factors like chronic stress[14]. However investigations commonly fail to find a cause[13,14]. Neurohormonal factors might play a role in the pathogenesis of FD. The secretory ability or the metabolic condition of ghrelin may be altered in FD patients, leading to delayed gastric emptying[15]. Also natriuretic peptides effect inhibitory regulations in gastric motility[16]. Other disturbances in serum parameters like incretion and adipocytokines may produce abnormal gastric motility, too[17]. Furthermore, asymmetric geometry of the pyloric orifice in concert with intermittent gastric outflow may affect gastric effluent homogenization with duodenal secretions[18].

Although the distended condom in the current study was considered to represent a food bolus, yet a study is being planned to investigate the effect of a test meal on pressure recordings in DD, DJJ, and JJ.

In conclusion, the current study has shown that, in contrast to the healthy volunteers in whom the DJJ opens on DD distension, the DDJ did not open in the patients. We call this condition ‘duodeno-jejunal junction dyssynergia syndrome’ (DJJDS). This condition probably leads to chyme stagnation in the DD and explains the clinical manifestations of the patients. The cause of DJJDS is not known and needs to be studied.

Margot Yehia assisted in preparing the manuscript.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Alpini GD E- Editor Yin DH

| 1. | Brown BP, Schulze-Delrieu K, Schrier JE, Abu-Yousef MM. The configuration of the human gastroduodenal junction in the separate emptying of liquids and solids. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:433-440. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Houghton LA, Read NW, Heddle R, Horowitz M, Collins PJ, Chatterton B, Dent J. Relationship of the motor activity of the antrum, pylorus, and duodenum to gastric emptying of a solid-liquid mixed meal. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:1285-1291. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Kelly KA. Gastric emptying of liquids and solids: roles of proximal and distal stomach. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:G71-G76. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Fuchs KH, Maroske J, Fein M, Tigges H, Ritter MP, Heimbucher J, Thiede A. Variability in the composition of physiologic duodenogastric reflux. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:389-95; discussion 395-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Keane FB, Dimagno EP, Malagelada JR. Duodenogastric reflux in humans: its relationship to fasting antroduodenal motility and gastric, pancreatic, and biliary secretion. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:726-731. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Bechi P, Cianchi F. Technical aspects and clinical indications of 24-hour intragastric bile monitoring. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:54-59. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Didio LJA, Anderson MC. The 'Sphincters' of the digestive system. Didio LJA, Anderson MC, editors. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins 1968; 86-112. |

| 8. | Villemin F. Recherches d'anatomie compare sur le duodenum de l'homme et des mammideres. Sa signification morphologique et functionelle. Arch Morphol Genel Exp. 1922;3:1-142. |

| 9. | Ochsner AJ. VIII. Construction of the Duodenum Below the Entrance of the Common Duct and Its Relation to Disease. Ann Surg. 1906;43:80-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Skandalakis JE. Small intestine. The Embryologic and Anatomic Basis of Modern Surgery. Skandalakis JE, editor. Athens, Greece: Pascalidis Medical Publications 2004; 791-839. |

| 11. | Shafik A, El Sibai O, Shafik AA, Shafik IA. Demonstration of a physiologic sphincter at duodeno-jejunal junction. Front Biosci. 2006;11:2790-2794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Meyer JH. Motility of the stomach and the gastroduodenal junction. Johnson LR, Christiensen J, Jackson MJ, Jacobson ED, Walsh JH, editors. New York: Raven Press 1987; 613-630. |

| 13. | Keohane J, Quigley EM. Functional dyspepsia: the role of visceral hypersensitivity in its pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2672-2676. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Suzuki H, Nishizawa T, Hibi T. Therapeutic strategies for functional dyspepsia and the introduction of the Rome III classification. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:513-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Takamori K, Mizuta Y, Takeshima F, Akazawa Y, Isomoto H, Ohnita K, Ohba K, Omagari K, Shikuwa S, Kohno S. Relation among plasma ghrelin level, gastric emptying, and psychologic condition in patients with functional dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:477-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xing DG, Huang X, Li CH, Li XL, Piao LH, Gao L, Zhang Y, Kim YC, Xu WX. Muscarinic activity modulated by C-type natriuretic peptide in gastric smooth muscles of guinea-pig stomach. Regul Pept. 2007;143:83-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kaji M, Nomura M, Tamura Y, Ito S. Relationships between insulin resistance, blood glucose levels and gastric motility: an electrogastrography and external ultrasonography study. J Med Invest. 2007;54:168-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dillard S, Krishnan S, Udaykumar HS. Mechanics of flow and mixing at antroduodenal junction. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1365-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |