Published online Aug 14, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i30.4042

Revised: May 1, 2007

Accepted: May 12, 2007

Published online: August 14, 2007

Hilar tumors have proven to be a challenge to treat and manage because of their poor sensitivity to conventional therapies and our inability to prevent or to detect early tumor formation. Endoscopic stent drainage has been proposed as an alternative to biliary-enteric bypass surgery and percutaneous drainage to palliate malignant biliary obstruction. Prosthetic palliation of patients with malignant hilar stenoses poses particular difficulties, especially in advanced lesions (type II lesions or higher). The risk of cholangitis after contrast injection into the biliary tree in cases where incomplete drainage is achieved is well known. The success rate of plastic stent insertion is around 80% in patients with proximal tumors. Relief of symptoms can be achieved in nearly all patients successfully stented.

- Citation: Palma GDD, Masone S, Rega M, Simeoli I, Salvatori F, Siciliano S, Maione F, Girardi V, Celiento M, Persico G. Endoscopic approach to malignant strictures at the hepatic hilum. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(30): 4042-4045

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i30/4042.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i30.4042

Extrahepatic malignant stenoses have traditionally been separated into three groups, based on anatomical location. Upper third or hilar tumors are those located in the common hepatic duct and/or the right and left hepatic ducts including their confluence. Middle third tumors occur in the region bounded by the upper border of the duodenum and extending to the common bile duct. Lower third or distal bile duct tumors arise between the ampulla of Vater and the upper border of the duodenum.

Malignant biliary obstruction at the liver hilum is caused by a heterogeneous group of tumors that includes primary bile duct cancer (the so-called Klatskin tumor), cancers that involve the confluence by direct extension (e.g., gallbladder and liver cancer), and metastatic cancer to hilar lymphatic nodes or to the liver or biliary tree.

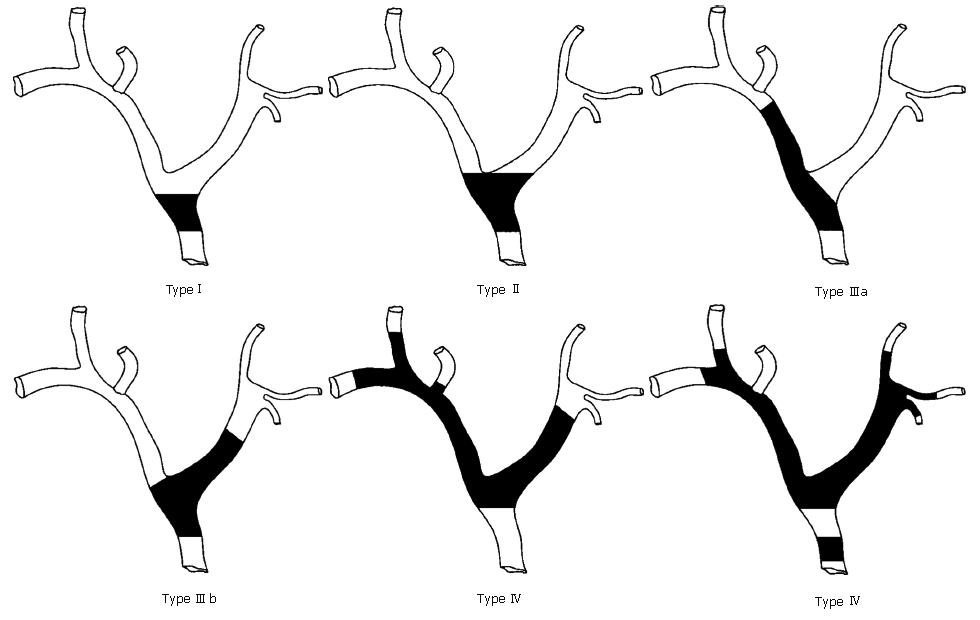

The extent of duct involvement by perihilar tumours may be classified as suggested by Bismuth and Corlette[1]: A. typeI: tumors below the confluence of the left and right hepatic ducts (ceiling of the biliary confluence is intact; right and left ductal systems communicate); tumors reaching the confluence but not involving the left or right hepatic ducts (ceiling of the confluence is destroyed; bile ducts are separated); C. type III: tumors occluding the common hepatic duct and either the right (IIIa) or left (IIIb) hepatic duct; D. type IV: multicentric tumors or tumors involving the confluence and both hepatic ducts, the right one and the left one (Figure 1).

Hilar tumors have proven to be a challenge to treat and manage because of their poor sensitivity to conventional therapies and our inability to prevent or to detect early tumor formation. Untreated patients usually die within 6 mo to a year after diagnosis.

The range of therapeutic modalities varies from a curative approach by performing extensive liver resections-in some cases even total hepatectomy and liver transplantation-to a more palliative approach in which a surgical bypass or even percutaneous or endoscopic stent insertion is undertaken, with or without radiotherapy.

All patients should be fully evaluated for resectability before any type of intervention is performed because stent-associated inflammation or infection often makes assessment more difficult.

Patients being evaluated for resectability must at first be physiologically suitable for a potential operative resection that may include a partial hepatectomy. The patient’s nutritional status and risk of postoperative liver failure are important factors to consider before proceeding to exploration for resection. A retrospective review of resected hilar cholangiocarcinoma cases demonstrated that a preoperative serum albumin level < 3 g/dL and a total bilirubin level > 10 mg/dL were both associated with poorer survival[2].

Since the vast majority of extrahepatic strictures, particularly hilar strictures are the result of a cholangiocarcinoma, histological diagnosis is not mandatory before exploration.

The diagnosis of malignant biliary strictures depends on the identification of tumor cells obtained by ultrasound (US) or CT-guided percutaneous fine needle aspiration, bile sampling, endobiliary brushings, or bile duct biopsies. Percutaneous needle biopsies are reliable only if US or CT identifies a malignancy (sensitivity of 50%).

Bile samples, obtained through a percutaneous or endoscopic stent, contain cancerous cells in 30% to 40% of cases of cholangiocarcinoma. The use of brush biopsy and cytologic examination may increase the yield to 40% to 70%. Unfortunately, even percutaneous or endoscopic biopsy not infrequently yields non-diagnostic tissue because of the desmoplastic nature of the lesion.

In the absence of clear evidence of unresectability, all suspected lesions should be considered for resection.

Endoscopic stent drainage has been proposed as an alternative to biliary-enteric bypass surgery and percutaneous drainage to palliate malignant biliary obstruction. In addition, alternative approaches to biliary stent placement have been compared with particular interest in determining optimal stent material, design, and placement strategies[3-7].

Prosthetic palliation of patients with malignant hilar stenoses poses particular difficulties, especially in advanced lesions (type II lesions or higher). The risk of cholangitis after contrast injection into the biliary tree in cases where incomplete drainage is achieved is well known. Retention of contrast and subsequent segmental cholangitis is a risk associated with endoscopic attempts to treat advanced hilar lesions and this has prompted some to question the role of endoscopic drainage in this situation[8].

Some studies suggest that patients undergoing stent placement for malignant low bile duct obstruction had significant improvement in abdominal discomfort, weight loss, or anorexia and sleep patterns, in addition to the expected improvement in pruritus and jaundice[9]. Similar studies would be needed to confirm that endoscopic stent placement of hilar obstruction is associated with an improved quality of life and can be justified by economic considerations.

Although metabolic and immune parameters appear improved with biliary drainage, there has been no evidence that endoscopic stent placement translates into prolonged survival. The success rate of plastic stent insertion is around 80% in patients with proximal tumors. Relief of symptoms can be achieved in nearly all patients successfully stented.

Technique of stent implantation: The options include draining only the left hepatic system, draining only the right hepatic system, or draining both systems.

The decision whether to place a single biliary stent or multiple stents depends initially on the location of the stricture in the biliary tract.

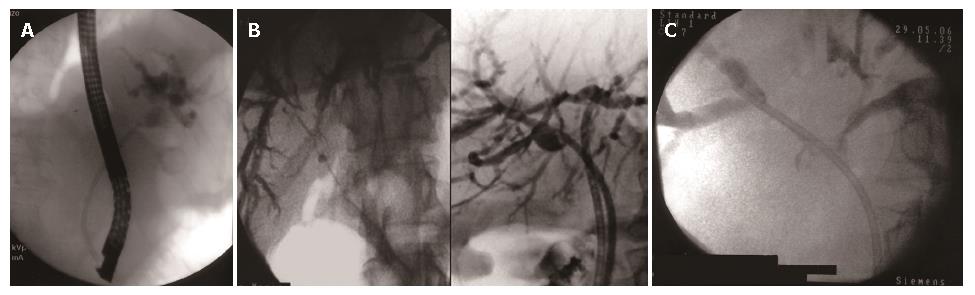

In patients who have strictures that do not involve the confluence of right and left hepatic ducts (Bismuth typeIhilar strictures), jaundice can be palliated completely with a single biliary stent because both the right and left intrahepatic ductal systems are in communication (Figure 2A).

In patients who have more complex strictures (Bismuth type II to IV strictures) the central question is whether adequate palliative relief of obstruction requires the placement of two endoprostheses, one to drain the left system and one to drain the right, or if one prosthesis placed in either system will suffice (Figure 2B and C).

Palliation of jaundice generally requires drainage of 1/4 to 1/3 of a healthy liver, or proportionally more in those with underlying dysfunction. Hence unilateral drainage is usually adequate, and many studies have reported good results using a single stent in about 80% of patients with type II and III tumors. No difference in efficacy has been shown between single stent placement in the left or the right system.

Really, the necessity to ensure the drainage of both systems, including additional endoscopic or percutaneous stent, if necessary, pertains more to the prevention of procedure-induced cholangitis caused by contrast injection in undrained biliary branches than to effective palliation. Generally, if both lobes are imaged with contrast during cholangiography bilateral stenting reduces the potential sequelae of cholangitis in contaminated but undrained areas. If contrast does not contaminate both sides then unilateral stenting should be sufficient[10-13].

Patients with multiple intrahepatic strictures will probably not benefit from any type of drainage procedure, if several segments (> 1/4) will always remain undrained. In the absence of intractable symptoms, it is probably recommendable that these patients should not undergo further endoscopic measures, as the risk of inducing cholangitis outweighs any benefits that could be possibly realized from the establishment of the endoscopic drainage.

Recent reports describe the utility of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or CT imaging to guide selection of the target lobe for subsequent endoscopic stenting, often without use of contrast[12,13].

Selection of the stent (plastic or metal): Theoretically, a metal stent should result in better drainage than a plastic stent in hilar strictures.

The metal stents have two advantages over the plastic stents: it does not occlude side branches because of the multiple meshes; furthermore, because most hilar tumors are firm and scirrhous, tumor ingrowth probably occurs less frequently.

Metallic stents offer longer but still limited stent patency duration of about 4 to 6 mo compared with a patency duration of 2 to 4 mo for plastic stents.

In contrast to plastic stents, metallic stents are not removable after the first few days of deployment, as the stent becomes embedded in the tumor tissue, which may grow into each of the individual mesh opening. Thus, metallic stents should be used in patients with proven unresectable malignancies, because initial insertion of an expandable metal stent makes subsequent surgery more difficult as these stents cannot be readily removed surgically.

The main disadvantage is the cost of the metallic stent (USD 900-1200), and identification of patients who are likely to out-live their first plastic stent, and warrant a metal stent, is a major challenge for the managing clinician. Cost analysis showed that metallic stents were advantageous versus plastic stents in patients surviving more than 6 mo and very costly when patients survived less than three months. Therefore, the use of metal stents should be restricted to those patients with unresectable tumors who will, in all probability, live longer than 3 mo. Unfortunately there is no good way to predict life expectancy at this time. Tumor size (> 3 cm), evidence of diffuse liver metastases, and general condition of the patient could guide the choice of stent.

The evaluation of patients with suspected malignancy of the hepatic hilum should include helical or multislice CT of the abdomen. An MRCP should be obtained to assess for resectability. If the disease is resectable and the patient is fit, surgical resection of the lesion should be performed. Preoperative ERCP should be avoided unless there is cholangitis or significant delay in surgery and the patient is symptomatic. If the lesion is unresectable or the patient is unfit for surgery, then endoscopic palliation of jaundice should be performed by using the MRCP as a guide for unilateral drainage to minimize cholangitis. If cholangitis occurs, ERCP or a percutaneous approach to drain the obstructed lobe of the liver should be performed promptly. The use of metal stents should be restricted to those patients who will, in all probability, live longer than 3 mo.

Hilar tumors have proven to be a challenge to treat and manage because of their poor sensitivity to conventional therapies and our inability to prevent or to detect early tumor formation. Endoscopic stent drainage has been proposed as an alternative to biliary-enteric bypass surgery and percutaneous drainage to palliate malignant biliary obstruction.

Alternative approaches to biliary stent placement have been compared with particular interest in determining optimal stent material, design, and placement strategies.

Recent reports describe the utility of MRCP or CT imaging to guide selection of the target lobe for subsequent endoscopic stenting, often without use of contrast.

Patients with malignant stenoses at hepatic hilum not suitable for surgery.

Malignant biliary obstruction at the liver hilum is caused by a heterogeneous group of tumors that include primary bile duct cancer (the so-called Klatskin tumor), cancers that involve the confluence by direct extension (e.g., gallbladder and liver cancer), and metastatic cancer to hilar lymphatic nodes or to the liver or metastases to biliary tree.

The authors reviewed about endoscopic approach to hilar malignant strictures, with a focus on endoscopic stent drainage, which has been proposed as an alternative to biliary-enteric bypass surgery and percutaneous drainage to palliate malignant biliary obstruction.

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor WangHF

| 1. | Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:170-178. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Gerhards MF, van Gulik TM, de Wit LT, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Evaluation of morbidity and mortality after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma--a single center experience. Surgery. 2000;127:395-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hawes RH. Diagnostic and therapeutic uses of ERCP in pancreatic and biliary tract malignancies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S201-S205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Strasberg SM. ERCP and surgical intervention in pancreatic and biliary malignancies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S213-S217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Flamm CR, Mark DH, Aronson N. Evidence-based assessment of ERCP approaches to managing pancreaticobiliary malignancies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S218-S225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rey JF, Dumas R, Canard JM, Ponchon T, Sautereau D, Helbert T, Escourrou J, Gay G, Giovannini M, Greff M. Guidelines of the French Society of Digestive Endoscopy: biliary stenting. Endoscopy. 2002;34:169-173, 181-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Baron TH, Mallery JS, Hirota WK, Goldstein JL, Jacobson BC, Leighton JA, Waring JP, Faigel DO. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and treatment of patients with pancreaticobiliary malignancy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Adler DG, Baron TH, Davila RE, Egan J, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, Qureshi W, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, Fanelli R. ASGE guideline: the role of ERCP in diseases of the biliary tract and the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Abraham NS, Barkun JS, Barkun AN. Palliation of malignant biliary obstruction: a prospective trial examining impact on quality of life. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:835-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chang WH, Kortan P, Haber GB. Outcome in patients with bifurcation tumors who undergo unilateral versus bilateral hepatic duct drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:354-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | De Palma GD, Galloro G, Siciliano S, Iovino P, Catanzano C. Unilateral versus bilateral endoscopic hepatic duct drainage in patients with malignant hilar biliary obstruction: results of a prospective, randomized, and controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:547-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hintze RE, Abou-Rebyeh H, Adler A, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Felix R, Wiedenmann B. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography-guided unilateral endoscopic stent placement for Klatskin tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:40-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | De Palma GD, Pezzullo A, Rega M, Persico M, Patrone F, Mastantuono L, Persico G. Unilateral placement of metallic stents for malignant hilar obstruction: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:50-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |