INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis is a potentially systemic disease that can affect any organ[1]. Extra-pulmonary organ involvement of tuberculosis is estimated to occur in 10% to 15% of the patients noninfected by HIV. With the increasing use of immunosuppressants and the emergence of AIDS, there has been a resurgence of tuberculosis and the frequency is about 50% to 70% in patients infected by HIV[2]. Abdominal tuberculosis is one of the most prevalent forms of extra-pulmonary diseases. Abdominal infection with tuberculosis commonly affects the spleen, liver and ileo-cecal region. Pancreatic tuberculosis is an extremely rare disease, especially when it is isolated in the pancreas[3]. The abdominal form of tuberculosis has an insidious course without any specific clinical, laboratory or radiological findings[4]. As a result, the diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis is correct in only 35%-50% of cases and a diagnostic delay is not unusual[5]. Most cases are not diagnosed preoperatively because special staining of biopsy specimens is necessary and cultures of the aspirate require prolonged incubation[6].

A case is presented that highlights the benefit of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for evaluation of pancreatic and peri-pancreatic lymphadenopathy tuberculosis. In particular, this case demonstrates the value to obtain suitable tissue samples by EUS fine needle aspiration, thus avoiding unnecessary surgical explorations.

CASE REPORT

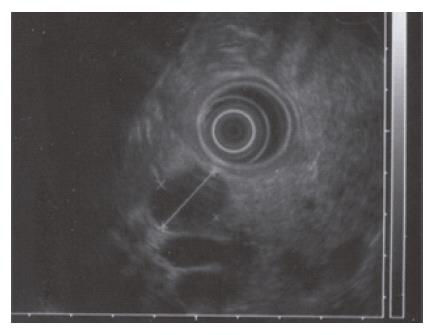

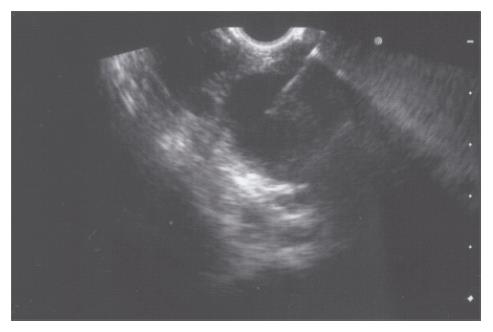

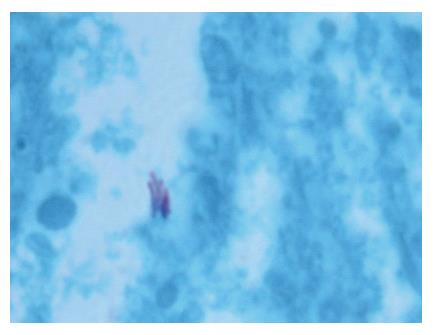

A 52-year-old woman, native of a small city in Lebanon, was admitted to the hospital for abdominal pain and fever. She was a cigarette smoker (60 pq/year) without excessive alcohol consumption and had a history of pulmonary embolism. She had been well until one month earlier, when mild epigastric pain developed. Four days before admission, the abdominal pain became constant and severe and nausea developed. She had also chills without frank rigors and a weight loss of 8 kg. The temperature was 38.5°C, the pulse was 100 beats/min, and the respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min. The blood pressure was 130/85 mmHg. On physical examination, the patient did not appear to be severely suffered and there was no jaundice. The lungs and heart sounds were normal. The abdomen was flat, and bowel sounds were present. There was a diffuse abdominal tenderness without rebound tenderness. No mass or hernia was detected. The arms and legs were well perfused. No abnormalities were found on rectal examination. The WBC was normal. C reactive protein (CRP) was moderately elevated (40 UI, normal < 6). The plasma levels of urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, electrolytes, bilirubin, amylase and lipase were normal. Activities of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase were normal. The total protein level was 75 g/L. A stool specimen was negative for occult blood. The urinalysis was normal. Serologic tests of wright and widal were normal. Radiographs of the abdomen in the supine and upright positions showed air-filled loops of the small bowel, without dilatation or air-fluid levels. No abnormal calcifications were identified. Abdominal and pelvic computed tomographic (CT) studies, performed after the oral and intravenous administration of contrast material, revealed a heterogeneously enhanced, multicystic structure, 3 cm in diameter, cephalad to the pancreatic head (Figure 1). The remainder of the pancreas was unremarkable. The liver, spleen, gallbladder, adrenal glands, kidneys, distal small bowel, colon, urinary bladder, and imaged bones were unremarkable, and no retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy was evident. EUS with a radial echoendoscope (GF-UM160; Olympus [key med], UK) revealed a large, 2-2.5 cm anoechoic, homogenous, well-defined mass, which lay adjacent to the neck of the pancreas (Figure 2). Another homogeneous tumor, 1 to 1.3 cm in diameter, was detected between splenic vessels. EUS-guided FNA (EUS FNA) of the peripancreatic lesion was performed using a linear-array echoendoscope (GF-UC 160P, Olympus) (Figure 3). Blood-stained cellular aspirates were obtained in a total of 2 passes with a 22-gauge needle (Echotip; Wilson Cook). An initial examination of the specimen was not diagnostic (squamous cells, macrophages, and inflammatory cells with no malignant tumor cells). Staining with Ziel Nielson within 30 min yielded a positive result for acid-fast bacilli (Figure 4). Although the patient had no personal or familial history of tuberculosis, the tuberculin test result was positive. The diagnosis of tuberculosis was adopted, and we initiated a four-drug regimen. She was treated with that regimen for 2 months and tolerated it well.

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomograph revealed a heterogeneously enhanced, multicystic structure, 3 cm in diameter, cephalad to the pancreatic head.

Figure 2 EUS with a radial echoendoscope revealed a large, 2-2.

5 cm anoechoic, homogenous, well-defined mass which lay adjacent to the neck of the pancreas.

Figure 3 EUS-guided FNA of the peripancreatic lesion was performed using a linear-array echoendoscope.

Figure 4 Staining with Ziel Nielson within 30 min yielded a positive result for acid-fast bacilli.

DISCUSSION

Tuberculosis of the pancreas and peripancreatic lymph nodes in immunocompetent patients is rare and could present a diagnostic challenge[1]. The main symptoms are non-specific: epigastric pain, fever, anorexia and weight loss. The duration of symptoms prior to presentation ranges from 5 d to 5 mo[7]. This rare infection usually starts in the peripancreatic lymph nodes and initially spares the pancreas[8]. Tuberculosis can affect the pancreas either by contiguous spread from the peripancreatic lymph nodes or by hematogenous spread[9].

The diagnosis remains difficult and it is especially difficult to differentiate pancreatic tuberculosis from a pancreatic tumor[1]. Lesions resulting from mycobacterial infection of the pancreas are often complex and cystic and they mimic cystic neoplasms of the pancreas[10-11]. Their cystic nature and the finding of rim enhancement on CT studies probably reflect the presence of central necrosis[12]. The diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis classically requires microbiological and culture confirmation of mycobacterium tuberculosis[13]. In the past, histopathological and/or bacteriological confirmation of the clinical suspicion of abdominal tuberculosis could only be obtained by an open surgical biopsy[14]. During recent years, fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) has been shown to be a safe, quick, reliable and cost-effective alternative for obtaining tissue for cytopathological and bacteriological examination[15]. US guided FNAC is widely accepted as an accurate and safe technique for obtaining tissue from lesions located in virtually any region of the body[16]. In a study by Das et al[17], US guidance helped in obtaining an adequate sample in a significantly higher percentage of cases (84.6%) compared with non-guided FNAC (61.5%). On the basis of cytomorphological analysis, results were classified into four groups as follows: (1) definite evidence of tuberculosis: epithelioid granulomas or necrotic material positive for acid-fast bacilli (AFB); (2) presumptive evidence of tuberculosis: epithelioid granulomas with or without necrosis but negative for AFB; (3) suggestive of tuberculosis, presence of necrotic material only with AFB negativity, but in an appropriate clinical setting and with characteristic radiological findings; (4) negative for tuberculosis, presence of atypical inflammation or inadequate material or non representative samples[14].

EUS has been shown to have a high sensitivity for detecting pancreatic masses, although its ability to distinguish a malignancy from an inflammatory disease may be limited[18]. EUS guided-FNA may detect a variety of pathologic processes in the pancreas, including malignant or benign neoplasms, pseudocysts, and reactive changes. Pancreatic EUS guided-FNA allows an accurate and safe diagnosis without the risk, the cost, and the time expenditure of an open biopsy or laparotomy. A review of the literature about image-guided FNA biopsy of the pancreas reveals a relatively high overall sensitivity (64%-98%), specificity (80%-100%), and positive predictive value (98.4%-100%)[19]. Recent technologic advances have made EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic lesions practical. In a study by Volmar et al[20], a logistic regression analysis showed that for lesions < 3 cm, the EUS-guided FNA method had higher accuracy than US or CT guided-FNA and no statistically significant difference was seen for larger lesions or for the number of FNA passes. Tumor seeding along a needle tract is an established complication of percutaneous sampling of pancreatic masses under CT or transcutaneous US guidance. The risk of peritoneal carcinomatosis appears to be lower with EUS-guided FNA compared with transcutaneous sampling methods[21]. This is a potential advantage often cited for EUS-FNA. For these reasons, EUS-guided FNA is the method of choice to obtain a tissue sample from the pancreas.

The present case illustrates the usefulness of EUS guided-FNA in the diagnosis of tuberculous lymphadenitis involving peripancreatic lymph nodes.

In conclusion, EUS guided FNA offers a safe and accurate method of achieving a diagnosis in patients with suspected abdominal tuberculosis who present with radiologically demonstrable lesions, especially involving the lymph nodes. EUS guided-FNA should be used as a first step in the diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis. A laparotomy should be performed only when complications develop or the diagnosis remains unclear in spite of these diagnostic modalities.

S- Editor Yang XX L- Editor Zhu LH E- Editor Bi L